There are many reasons policymakers across the world have been casting envious glances at the US’s shale gas boom: from falling energy prices to curbing emissions. But a range of geological, economic, and social obstacles have made it tricky to replicate elsewhere.

A new report from the World Resources Institute (WRI) thinktank, covered by Vox yesterday, highlights another: water availability.

Getting shale gas or oil out of the ground can be very water intensive. Known as fracking, it involves shooting large amounts of water and chemicals into the shale rock to create fractures through which the resources can be pumped. The International Energy Agency estimates it could require anywhere between a few thousand to 20 million litres of water per well.

That’s a problem, the WRI says, as many of the countries with the largest shale resources don’t have much water to spare.

Water availability

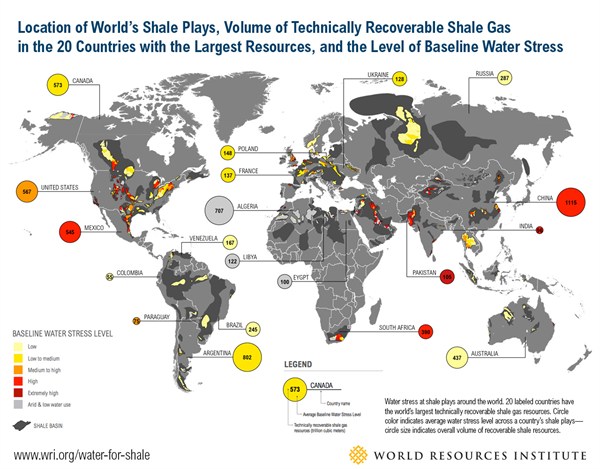

For the first time, the WRI has mapped global water availability alongside the location of the world’s shale resources. It finds that 38 per cent of the countries thought to have the largest shale resources also have strained water supplies.

The amount of water available to fracking companies depends on a number of factors. Perhaps most importantly, it depends on how much water is available in things like rivers and reservoirs. As the map below shows, many of the countries thought to have large shale oil and gas resources are also water stressed.

The size of the bubble refers to each country’s shale resources. The colour refers to how much water it’s thought to have spare – red means not much, light yellow means a lot:

Annual rainfall is another important factor. 19 per cent of the world’s shale resources are in places with highly variable seasonal rainfall, the WRI finds. 15 per cent are in areas exposed to drought.

That means that if companies were to frack in certain areas, they could find themselves competing for water with other industries and communities. 386 million people live above the world’s shale resources, the WRI finds. In 40 per cent of cases, agriculture is the area’s main water consumer.

That means the fracking industry could soon find itself embroiled in “conflicts with other water users” including local communities and the food industry, the WRI says.

Such conflicts could be particularly acute in China, where dense populations live in water stressed on top of large resources. Even the US’s fracking’s expansion may be curtailed as competition for water supplies starts to bite, the WRI claims.

UK

So what do the WRI’s findings mean for the UK, where the government has eagerly encouraged fracking?

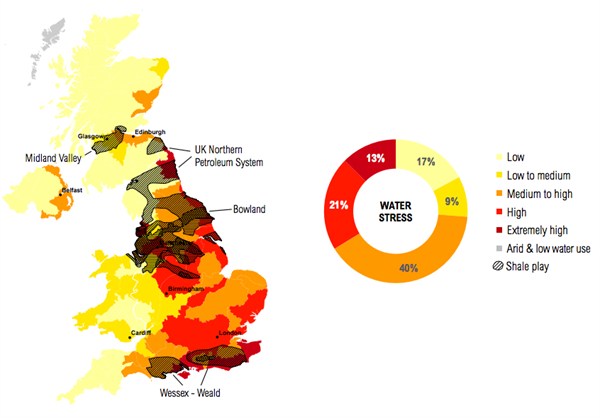

The WRI’s research shows three out of the UK’s four main shale fields are in water stressed areas:

Source: World Resources Institute, Figure A10: Shale plays and baseline water stress in the UK. Percentages refer to the ratio of water withdrawn compared to available renewable surface water.

Households are currently the main consumers in both the Bowland and Weald basin areas, the WRI’s research shows. Industry is the main user in the water stressed North East. Even rainy Lancashire already takes more water from the environment than it should.

That means fracking firms would be likely to compete for water in many areas, should they move in, according to industry group Water UK.

Regulations are being put in place to try and manage this. In England, fracking companies wanting to use groundwater will have to get a license from the Environment Agency. A licence will only be granted if the water can be taken in a way that “doesn’t harm the environment or other users”, the agency says.

But water firms don’t currently have to be consulted over fracking applications, running the risk of energy companies moving in where there’s already competition for water.

Water stress is a very local issue, with specific weather conditions and community needs all influencing availability. What the WRI’s report highlights is a question those with responsibility for water management must ask – is there space for fracking here?

On this evidence, the answer would often seem to be ‘probably not’.