Infographic: Mapping country alliances at the international climate talks

Rosamund Pearce

12.10.14Rosamund Pearce

10.12.2014 | 1:30pmUnder the surface of polite language and formal procedures, UN talks are more about realpolitik than they first appear.

Every country is out to further their own domestic interests, with weaker political forces banding together to have a chance of being heard against the more dominant players like the US, Russia and China.

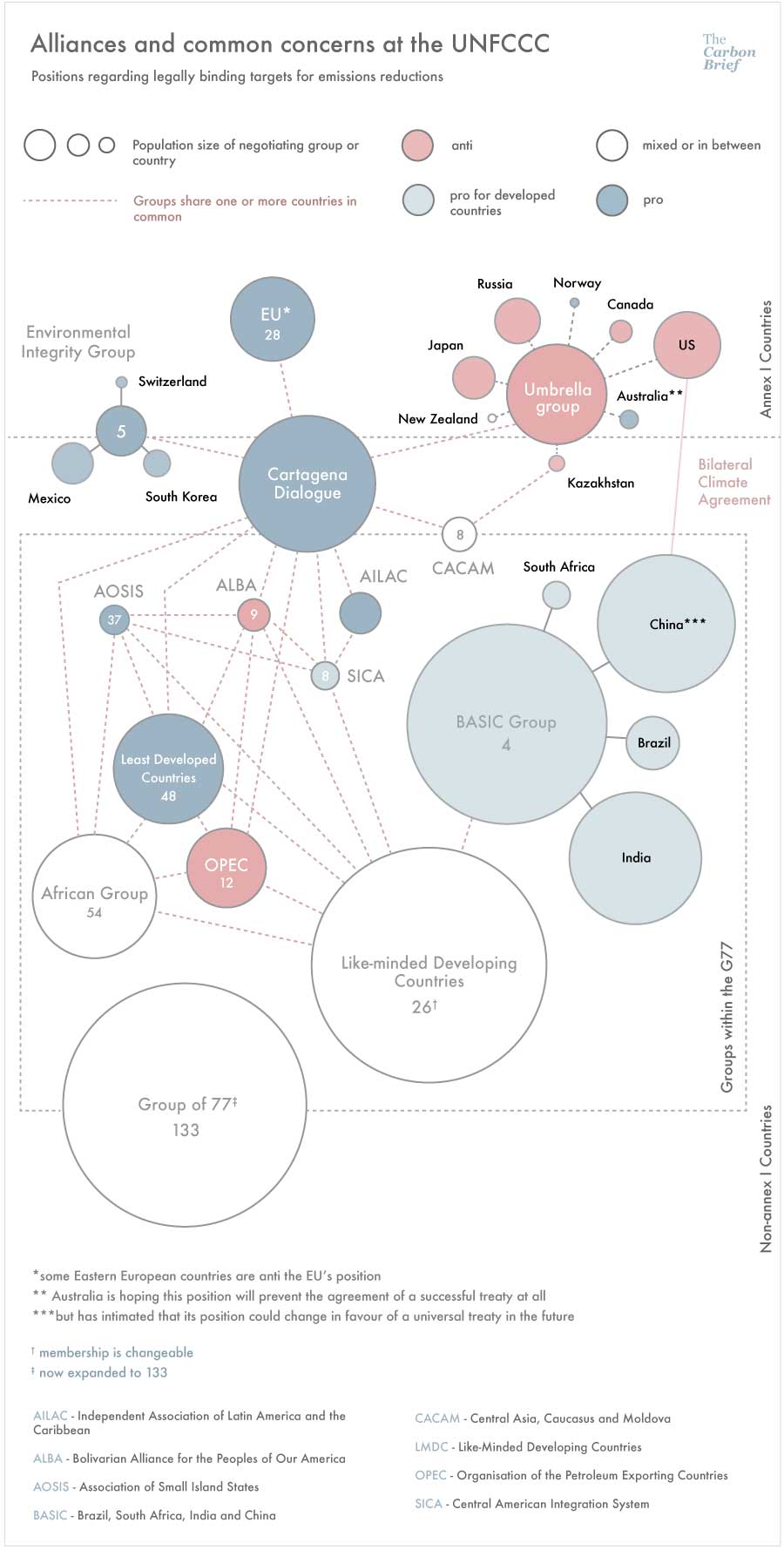

As talks continue in Lima, we’ve mapped what the negotiating groups are concerned about, how they link together, and how the recent development of a US-China climate agreement has stirred things up.

Mitigation and adaptation

There are four key issues that divide countries: whether a global climate agreement should be legally binding or not, who it should bind, how much aid to provide to help countries adapt to climate change, and whether compensation should be given to developing countries for the damage caused by climate change, a discussion known as ‘loss and damage’.

Traditionally the biggest divide has been between rich and poor countries. Less developed countries want compensation for the negative impacts of a problem they did little to cause, while developed nations such as the US want to avoid anything too stringent.

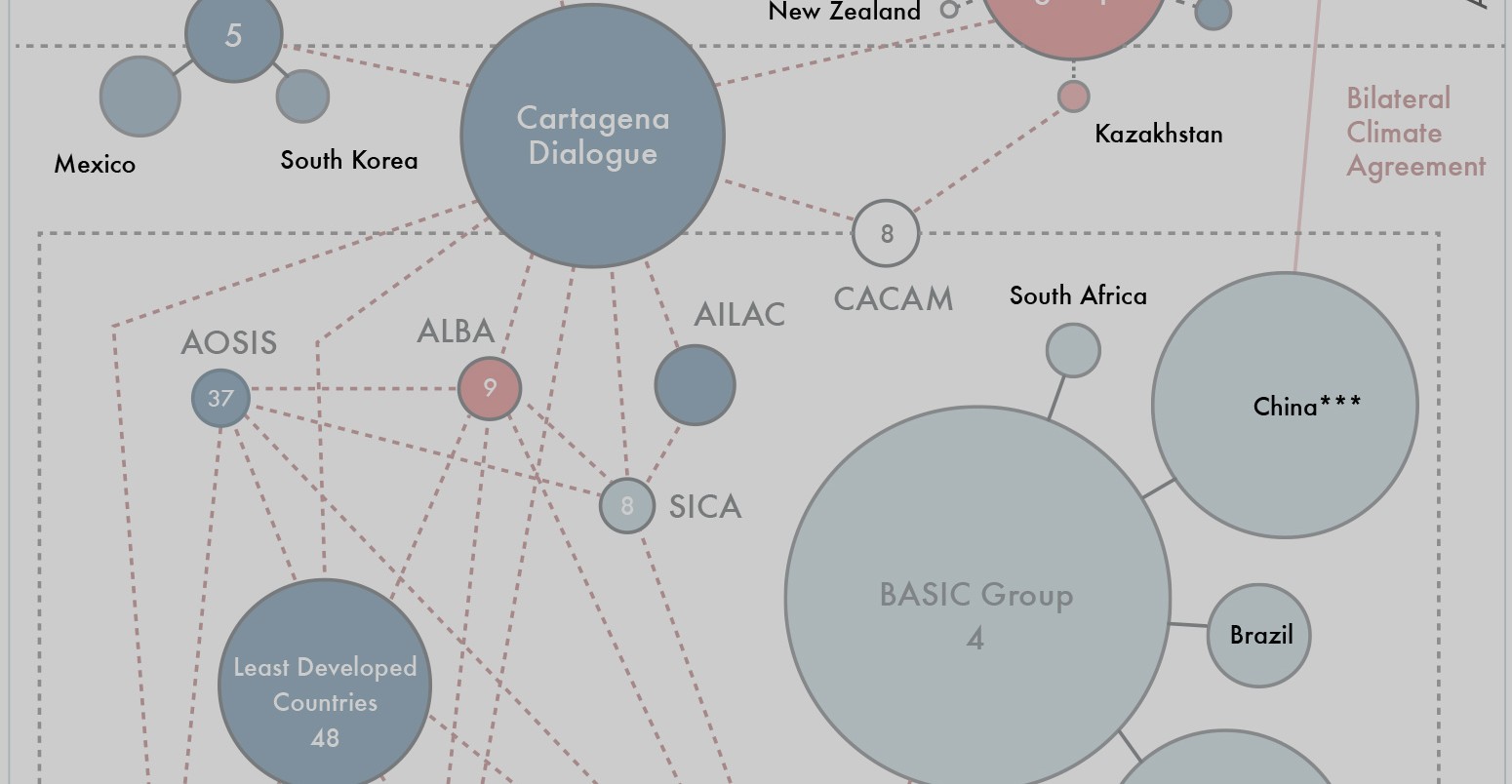

But the less developed nations are far from a unified bloc – in fact they comprise an increasingly complex and interconnected web of negotiating groups, with a range of priorities and positions.

A changing political scene

In January, Carbon Brief reported on how the political scene was becoming increasingly fragmented, with old alliances abandoned in favour of new groups. Groups such as the G77, a large association of developing nations, have become a mosaic of smaller groups, with often diverse objectives.

At one end of the spectrum lies the Alliance of Small Island States (AOSIS), a coalition of small island and low-lying coastal nations, who have an especially pressing interest in the fight against climate change. Their aim is to lobby for the strongest measures to combat climate change. At the other is the Organisation of Petroleum Exporting Communities (OPEC), including the likes of Nigeria, Venezuela, and Saudi Arabia, whose priority is to promote the interests of oil-producing countries, and who to try and block emissions reductions commitments.

As some developing countries have experienced rapid economic growth they have found it easier to move away from the bigger groups, to better push their own agenda. Chief among these groups is BASIC (Brazil, South Africa, India and China) an influential bloc of four newly industrialised nations, as well as the larger group of Like-minded developing countries (LMDC), a loose grouping of around 27 countries. Other alliances include the African Group and the Least Developed Countries group, both of which hope to prioritise the issue of financial aid.

The US-China deal

Last month, the US and China signed a historic climate deal, changing the face of international climate negotiations.

This has further “shaken up” the groups at the UNFCCC, says Farhana Yamin, director of environmental thinktank Track 0. She tells us that “many of the BASIC countries [have] very different positions on some of the core issues facing the Paris agreement, like the timing of when the commitments are submitted and how they are assessed”.

Previously, developing countries have acted together to further their common interests, including an orchestrated walk-out at previous talks in Warsaw.

Now BASIC are struggling to find common ground. By forging ahead with a climate deal, China has left its traditional partners behind, placed others under pressure to follow a similar route and made it harder to get away with inaction. Simultaneously, in its new position alongside the US, China has lost credibility as a champion of developing countries and with their BASIC partners.

The groups remain in place for the moment, but there are media reports that India is looking to distance itself from China. There is also a hope among the South American countries that the conference in Peru could push Brazil into making closer connection with the Latin blocs, such as AILAC (The Independent Association of Latin America and the Caribbean).

The like-minded developing countries are also struggling to stay cohesive. This time around, negotiators from the Philippines were withdrawn after their government discovered they were too friendly with other like-minded developing countries.

Other groups, however, have become more unified. AILAC has been taking a very consistent stance, trying to balance environmental concerns with their own national positions. AOSIS, too, has become a stronger voice, making frequent interventions over the last week.

What does all this mean for Paris?

Countries have set a deadline to agree a new global climate treaty at a conference in Paris next December, with this year’s conference in Lima providing an important opportunity to lay the groundwork for the deal.

Ultimately, countries must be able to bury their political differences in order for the conference in Paris to be a success. While such a feat may seem difficult between the fragmented and diverse negotiating groups, the “shaken-up” political scene could in fact prove an advantage, forcing countries to move from their gridlocked positions and follow China’s lead.

As proceedings move forward in Lima, and later in Paris, rhetoric will have to turn into action. This will prove the testing point of whether the current negotiating groups hold, or if there will be another shift in countries’ alignments on the issue of climate change.

Main image: Alliances and common concerns at the UNFCCC. Credit: Ros Pearce for Carbon Brief.

-

Infographic: Mapping country alliances at the international climate talks