Mat Hope

17.01.2014 | 2:00pmCommunities aren’t getting a fair share of the benefits of tackling climate change, according to a group of academics.

While governments may be trying to spread responsibility for cutting emissions, current policies are disadvantaging some of society’s most vulnerable groups, they argue.

So what can be done? A group of economists, political scientists, and sociologists sponsored by the Economics and Social Research Council gathered in Milton Keynes yesterday to explore how policymakers could make climate policy fairer.

1. Increasing accountability

While policymakers may somewhat vaguely claim climate policies will benefit local communities, they don’t always follow through on their promises, one of the academics found.

Countries signed the Kyoto Protocol in 1997, which allowed richer nations to fund climate policies in developing nations through the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM). The CDM is meant to help developing countries grow in a way that minimises greenhouse gas emissions, and provides other benefits for local communities.

As such, the South African government is helping Ghanaian farmers develop more environmentally friendly fertiliser, while the UK funds a hydroelectric plant in Peru. Those projects – and many others – are all implemented in the name of combating climate change.

But while the CDM has helped curb global emissions to an extent, countries haven’t always followed through on their promises to help the local communities where the projects are built. This is partly because all the pressure to show local benefits comes in the planning stages, University of Sussex professor, Peter Newell, says.

While the organisations may promise more jobs for the community, or investment in local infrastructure, they don’t have to prove they’ve done it once the projects are up and running, he says. In order to make the projects fairer, organisations should have to show they are fulfilling their original promises, he argues.

Until that happens, investors won’t have to account for the local benefits of their projects beyond offering vague promises at the outset.

2. Making governments pay

Conversation also turned to the unfairness of climate impacts. The poorest people in the world tend to have the smallest carbon footprints. Nevertheless, it is they who will suffer most from the impacts of climate change.

But current systems aren’t sufficient to deal with such disasters, the academics said.

Lancaster University’s Professor Gordon Walker argued that the recent floods showed just how unprepared the UK is for the impacts of climate change. He said this month’s events showed how society’s poorest could be hit hardest by natural disasters.

While it’s hard to attribute any one extreme weather event to climate change, scientists say the risks of flooding in the UK are increasing as the world warms.

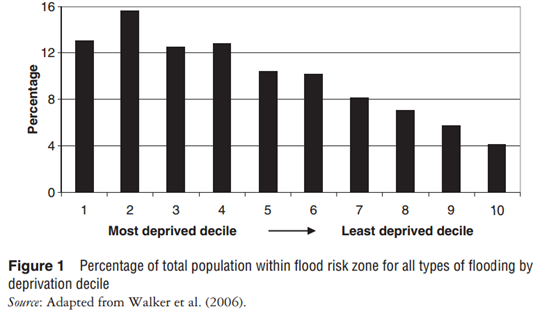

But in the UK, the people who are most at risk – and who can afford it least – may end up paying the most for flood insurance, he argues. The graph below shows many socially deprived areas are also at the highest risk of flooding:

That means they could end up paying more for flood insurance, as they’re more likely to have to make a claim. Walker says this is unfair as everyone is responsible for increasing emissions and not everyone can choose where they live.

He says the UK could learn some lessons from other EU countries on how to make its flood insurance schemes fairer. For instance, the Dutch government covers the total cost of any flooding in the Netherlands. That means everyone pays a bit for the scheme through their tax, but everyone shares in the benefits.

The UK government has made small steps in that direction. Under the government’s new scheme – called Flood Re – all homeowners will pay a small amount towards the cost of insuring homes in high-risk areas. But there are concerns the government has underestimated how many homes are at risk, so the scheme won’t cover some of the most vulnerable – and most needy – households.

3. Blame society, not individuals

But it’s not just specific policies the academics are worried about, it is policymakers’ wider approach to addressing climate change. Instead of trying to adjust how individuals behave – by encouraging them to make their homes more energy efficient through schemes such as the Green Deal, for instance – time would be better spent trying to change the way society goes about its day to day business they said.

But it’s unfair to expect individuals to be able to change their behaviour, Sociology professor Elizabeth Shove – also from Lancaster University – says.

For instance, individuals may have to drive to work, or get their power from an energy system dependent on coal. Neither or those polluting activities are necessarily the individual’s fault. As such, it’s unfair to blame them for climate change or put the responsibility for solving it at their feet, she says.

Instead, campaigners and academics should turn their attention to trying to change society’s wider polluting practices, she argues. Could we do without hot showers, for instance? And is moving towards an increasingly electrified world necessary? Instead of trying to tweak individuals behaviour, time could be better spent questioning why society requires people to use so much energy – and have such large carbon footprints – in the first place.

The academics argued that current climate policies aren’t reducing emissions effectively or fairly. By challenging some of the ways governments currently implement climate policy, they hope to recommend better ways of helping society tackle climate change.