In-depth: The UK should reach ‘net-zero’ climate goal by 2050, says CCC

Multiple Authors

05.02.19Multiple Authors

02.05.2019 | 12:49amThe UK should legislate for and reach a net-zero emissions goal by 2050, so as to end its contribution to global warming within 30 years.

That is the verdict of the Committee on Climate Change (CCC), the official adviser to UK government and devolved administrations in Scotland and Wales. Its 277-page advice is published today in response to a government request sent in October 2018.

The net-zero target should cover all greenhouse gases and should include international aviation and shipping, but exclude the use of emissions credits, the advice says. This would put the UK “at the top of the pile” relative to other net-zero goals, says CCC chief executive Chris Stark.

The goal could be met at a “manageable” cost, equivalent to 1-2% of GDP each year, the CCC says. But it would only be “credible” if accompanied by stronger policies to meet the new target, the CCC warns.

If adopted, the target would “fully meet the UK’s obligations under the Paris Agreement”, the committee says, with the UK reaching net-zero some 20 years ahead of the global average on a pathway to a 1.5C temperature limit.

In this in-depth Q&A, Carbon Brief explains why the advice was prepared, how the UK could reach net-zero emissions by 2050 and what will happen next.

- Why is the CCC giving this advice?

- What does the CCC recommend?

- Why should the UK go net-zero by 2050?

- How did the CCC come up with its findings?

- How does the target compare internationally?

- How could the UK reach net-zero?

- Net-zero goal: Electricity generation

- Net-zero goal: Homes

- Net-zero goal: Industry

- Net-zero goal: Road transport

- Net-zero goal: Farming and land use

- Net-zero goal: Aviation and shipping

- Will lifestyles need to change for net-zero?

- Does net-zero rely on negative emissions?

- Is fracking compatible with a net-zero target?

- What are the costs and benefits of net-zero?

- What happens next?

Why is the CCC giving this advice?

In 2015, almost every country of the world promised to reach net-zero emissions later this century as part of the Paris Agreement on climate change. The deal set a limit to global warming of “well-below” 2C above pre-industrial temperatures and said countries will “pursue efforts” to keep warming to 1.5C.

In contrast, the UK’s existing climate targets were set in the context of a 2C warming limit. Its overall goal, first set in 2008, has been to cut greenhouse gas emissions to 80% below 1990 levels by 2050.

In the wake of the raised ambition of the Paris deal, the government asked its official climate advisers, the Committee on Climate Change (CCC), what this should mean for the UK.

In two separate pieces of advice in 2016, the CCC said that the UK would ultimately have to raise its ambition for 2050, to match the Paris goals, but that it was not the time for doing so.

Under the Climate Change Act 2008, the UK has legally binding five-yearly carbon budgets, which mark staging posts on the way towards the “80% by 2050” goal. So far, the first five carbon budgets have been set down in legislation, covering 2008-2032.

The Act, which also established the CCC, sets a legal framework for changing the 2050 target in light of “significant developments in scientific knowledge about climate change, or European or international law or policy”. The relevant section of the Act is shown below:

The Act itself could also be amended to make other changes – for example, to set a different year for the UK’s long-term goal. See below for more on these options and what must happen next.

On 8 October 2018, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) published a special report on 1.5C that clearly set out the risks of allowing warming to exceed this level. This report also summarised the latest scientific evidence on what would be needed to stay below 1.5C.

Following this report, on 15 October 2018, the governments in Westminster, Cardiff and Edinburgh asked collectively the CCC for advice on when the UK should cut its emissions to net-zero.

Their letter asked whether the UK should set separate targets for CO2 and other greenhouse gases (GHGs). It asked “whether now is the right time for the UK to set such a target” in legislation. And it asked how the UK would reach net-zero, as well as the costs and benefits of doing so.

Today’s advice from the CCC is its response to this formal request. It comprises 277 pages of advice to the three governments, covering each of the questions posed by their October letter.

This advice is backed by another 300-odd pages setting out the significant changes in scientific knowledge and international policy that have taken place since the UK’s existing 2050 target was set. Behind the scenes are numerous research projects, technical annexes and advisory groups.

What does the CCC recommend?

The CCC says the UK should cut its greenhouse gas emissions to net-zero by 2050. This would be a significant increase on the existing target of an 80% cut by that year.

Moreover, the committee says this goal should be as broad as possible. This means it should include the UK’s significant shares of international aviation and shipping and exclude the use of international emissions credits, whereby the UK would pay for cuts overseas. The CCC says:

“By reducing emissions produced in the UK to zero, we also end our contribution to rising global temperatures…but it is essential that the commitment is comprehensive, achieved without the use of international credits and covering international aviation and shipping.”

This approach is in line with previous CCC advice, though neither of these broader requirements have ever been set down in law. Instead, the UK’s 2050 target and its five-yearly carbon budgets have been fixed with a separate amount set aside for international aviation and shipping.

The government has also so far accepted CCC advice to avoid the use of emissions credits or the “flexibilities” under the Act that allow overachievement to be carried forward to meet future budgets. It remains to be seen how these matters will be dealt with in future.

[CCC chief executive Chris Stark tells Carbon Brief he will be “watching closely” when the government responds to its latest letter on the use of flexibility from overachievement in the second carbon budget period. “If they try to do that it’ll be a sign they’re not taking it seriously,” Stark adds.]

The UK’s historical emissions are shown with a blue line in the shaded area of the Carbon Brief chart, below, while projected emissions to 2032 are shown in light blue. These are set against the existing carbon budgets, shown as five-yearly steps in red, plus the existing and proposed 2050 goals.

Historical UK greenhouse gas emissions (dark blue line and shaded area, millions of tonnes of CO2 equivalent) and government projections to 2032 (light blue). These are set against the first five carbon budgets (red steps) and a net-zero target for 2050 (red line), as well as the current 80% by 2050 target (dashed yellow). Note that emissions since 2008 and the projections to 2032 show the UK’s “net carbon account”. The 80% by 2050 target shown here includes the CCC’s 40MtCO2 allowance for international aviation and shipping, which are not currently included in the carbon budgets. This effectively entails an 85% cut for the rest of the economy. Source: Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy emissions data and projections, plus Carbon Brief analysis. Chart by Carbon Brief using Highcharts.The advice recommends that Scotland set a slightly more ambitious target of reaching net-zero by 2045. This is to reflect “Scotland’s greater relative capacity to remove emissions than the UK as a whole”, through afforestation and the restoration of degraded peat.

For Wales, the committee says the 2050 goal should be for a 95% reduction on 1990 levels. This is due to its relatively lower potential for CO2 storage and relatively high agricultural emissions.

The CCC’s advice goes on to set out the implications of a net-zero 2050 goal for each sector of the economy, as well as the costs and benefits of getting there, both covered in more detail below.

The advice also includes stern words on the need for stronger government policy, without which a more ambitious target for 2050 would amount to empty rhetoric. The CCC says:

“Our advice is offered with the proviso that net-zero is only credible if policies are introduced to match…Current policy is insufficient for even the existing targets…A UK net-zero GHG target in 2050 is feasible, but will only be deliverable with a major strengthening and acceleration of policy effort.

“Challenges across sectors must be tackled vigorously and in tandem, beginning immediately. That should be the clear understanding for the governments and parliaments of the UK, Scotland and Wales when considering the recommended targets.”

The CCC advice notes that emissions cuts to date have been heavily concentrated in electricity generation, waste and industry – whereas homes, transport and farming have done far less well.

In February, the committee said government was falling short of the progress required in 15 out of 18 areas, from the numbers of homes being insulated to the area of trees being planted each year.

The advice adds that the UK is set to miss its fourth and fifth carbon budgets, as shown in the chart, above. This leaves an increasingly large gap between what the UK has promised to do and what it is on track to achieve, even before considering a tougher 2050 goal.

Why should the UK go net-zero by 2050?

A lengthy section of the CCC advice explains why it is recommending a net-zero target for 2050, covering all greenhouse gas emissions in the UK.

First, it establishes that recent events satisfy the test in the Act that can trigger changes to the UK’s targets, namely “significant developments in scientific knowledge or…international law or policy”. The Paris Agreement and the IPCC’s 2018 report on 1.5C clearly meet this threshold, it says.

Then, the advice looks at what targets the UK should set to meet the Paris Agreement’s aims, including its requirement for countries to offer their “highest possible ambition”.

Broadly speaking, the justification for net-zero by 2050 rests on scientific imperative, practical feasibility and manageable costs. (“We conclude that net-zero is necessary, feasible and cost-effective.”) These factors are weighed in an international context considering the UK’s capability to act, its historical responsibility for emissions and its potential to inspire others.

The starting point is the latest science on limiting warming in line with the Paris deal. Greenhouse gas emissions pathways compatible with a 1.5C limit are shown in the chart below with a red shaded area and line, while “well-below” 2C trajectories are shown in blue.

Global greenhouse gas emissions pathways consistent with limiting warming to “well-below” 2C (blue shaded area and line) or 1.5C (red), in billions of tonnes of CO2 equivalent per year (CO2e/yr). Source: Hupperman et al (2018) reproduced in the CCC advice.

The committee defines “well-below” 2C scenarios as those that have a greater than 66% chance of keeping warming below 2C this century and a median temperature rise of 1.6-1.8C.

For the 1.5C limit, it includes pathways with at least a 50% chance of staying below that level in 2100. [These are described in the IPCC’s 1.5C report as “low or no overshoot” scenarios.]

Global greenhouse gas emissions fall to net-zero around 2070 in 1.5C pathways, the CCC notes, while the world’s CO2 output reaches zero somewhat earlier, around 2050.

The CCC then lays out why the UK should reach net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050, some 20 years earlier than the global average for 1.5C. [This implies the UK reaching net-zero CO2 emissions in the 2040s, Mike Thompson, CCC head of carbon budgets tells Carbon Brief.]

The reasons for the UK to move earlier include the fact that it is a wealthy country with established policies in place and a population that is “generally supportive” of climate action, the CCC says.

[A YouGov poll this week found that the number of people naming climate change among the country’s top three issues has recently surged to its highest level in at least a decade.]

There are also strong equity considerations that point to earlier UK action, the CCC says. The UK has “large cumulative historical emissions” that are well above the global average, as well as a “significant carbon footprint” in other countries attached to imported products.

[Responding to the idea that the UK should set targets against its consumption-based emissions, Thompson tells Carbon Brief that the international standard of territorial accounting remains more appropriate. “Fundamentally, this is about where the levers are as to what the UK can control,” he says, adding that imported emissions would fall if global efforts to cut carbon succeed.]

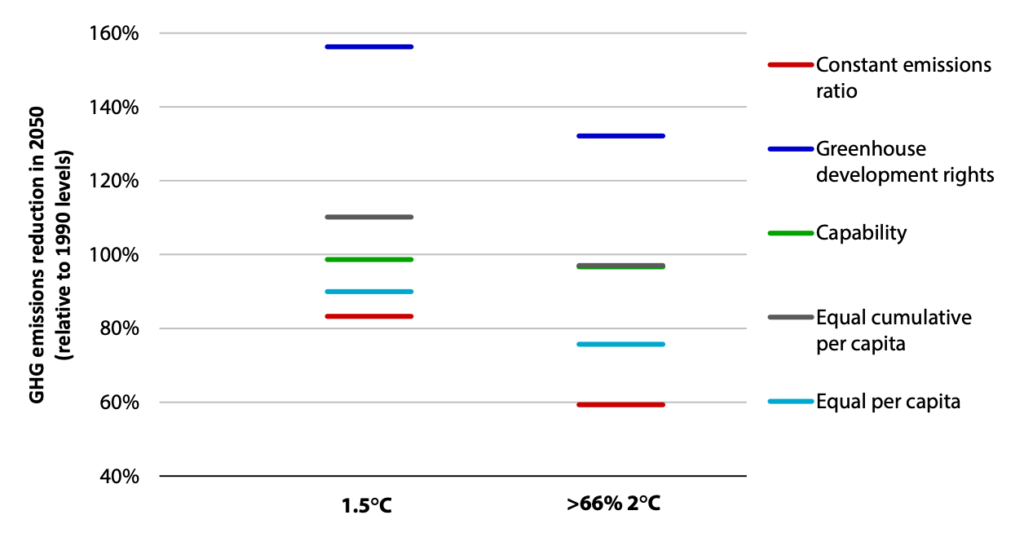

The CCC advice includes the chart, below, showing a range of 2050 targets for the UK depending on difference approaches to equity. The details of these approaches is less important than the fact that the CCC’s net-zero by 2050 recommendation lies roughly in the middle of the range.

Alternative 2050 emissions reduction targets for the UK based on a range of approaches to international equity. Source: du Point et al. (2016) reproduced in the CCC advice.

Explaining the CCC’s decision to select a 2050 net-zero target, Thompson tells Carbon Brief that it would not have been helpful to aim beyond what the UK could credibly achieve. “This, we think, is our highest possible ambition,” he says.

Stark adds: “We worried a lot about setting a target that wouldn’t last or quite swiftly wouldn’t be achieved. That’s something we always have to consider as a technical body.”

The CCC’s advice says:

“We base the scenarios on the latest understanding of existing technologies and expected improvements without assuming radical breakthroughs. We recognise the possibility that innovation could progress more rapidly than we have assumed, particularly as technologies are deployed at very large scale in the UK and beyond. Against this, there could be underperformance in some existing technologies or failures of policies to successfully drive change.”

This cautious approach is reflected in the way the CCC has written its advice, with tightly-worded language and repeated uses of the word “credible”. This seems designed to allow the minimum possible scope for government to reject its advice. On the other hand, this language is also used to push back on the idea of adopting an earlier net-zero target for the UK. The report says:

“Based on our current understanding, [2050] is the latest date for the UK credibly to maintain its status as a climate leader and the earliest to be credibly deliverable alongside other government objectives…A 100% cut in GHG emissions by 2050 is the minimum effort required to demonstrate clear consistency with the Paris goals and that the UK is taking a lead as a richer developed nation with high historical emissions.”

If the UK were to adopt a weaker target, it could “undermine” moves to set 2050 net-zero goals elsewhere, the committee says – particularly with regards to that proposed for the EU.

“It goes beyond the reduction needed globally to hold the expected rise in global average temperature to well below 2C and beyond the Paris Agreement’s goal to achieve a balance between global sources and sinks of greenhouse gas emissions in the second half of the century. If replicated across the world, and coupled with ambitious near-term reductions in emissions, it would deliver a greater than 50% chance of limiting the temperature increase to 1.5C.”

How did the CCC come up with its findings?

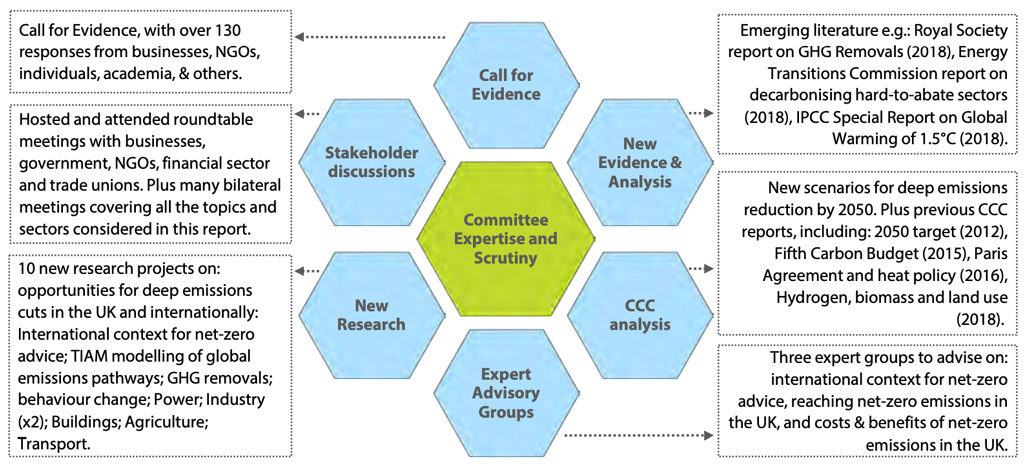

The CCC’s advice draws on an “extensive evidence base” of published work, 10 specially commissioned research projects, a public call for evidence and three expert advisory groups.

Its call for evidence asked 14 questions including climate science, opportunities for emissions cuts in the UK and the devolved administrations, and how the CCC should approach this work. In 133 responses there was “general support for a net-zero target” and a “strong call” for “clear and stable policies” to get there, it says, as well as calls for a “just transition” to net-zero that does not leave behind those working in high-carbon sectors.

The wider evidence base and the CCC’s associated analysis is set out in the graphic, below.

Structure of the engagement and analysis that informed the CCC’s net-zero advice. Source: graphic produced by CCC.

A significant new body of technical work and annexes is published today alongside the CCC advice. However, unlike the main report, it was not available for review ahead of publication.

How does the target compare internationally?

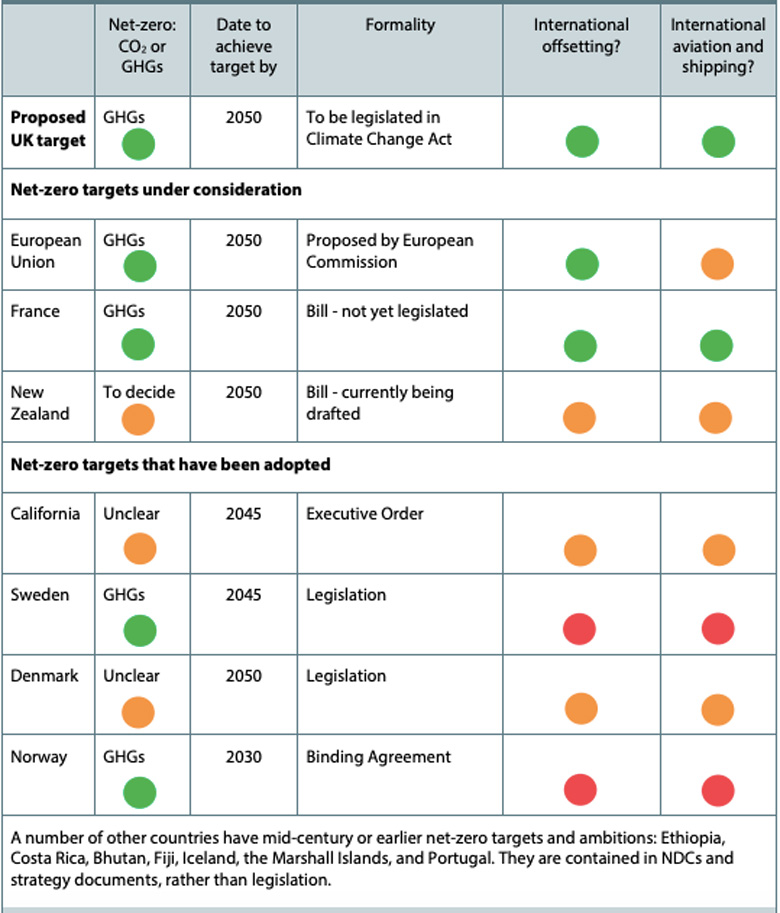

While the UK is not alone in considering a strategy to reach net-zero by the middle of the century, if the new target were to be adopted it could be seen as one of the most ambitious moves made by any nation yet.

In 2017, Sweden became the first country in the world to legislate for such a target, setting what, at first glance, seems like an even more pioneering goal of net-zero greenhouse gases by 2045. However, unlike the CCC’s plan, this commitment allows the use of carbon offsetting and does not include international aviation or shipping.

The inclusion of these two stipulations has, to date, made other commitments look rather less ambitious than the one being proposed for the UK.

Denmark has also passed net-zero legislation for 2050 to achieve a “carbon neutral society”, although it has not made its intentions clear regarding the use of carbon offsets or aviation and shipping. Norway, too, has made moves towards net-zero, with a parliamentary agreement to aim for 2030, but only with the help of carbon offsets and while ignoring planes and ships.

One more net-zero target that has actually been adopted is for the state of California, the world’s fifth largest economy. At last year’s Global Climate Action Summit in San Francisco, then-governor Jerry Brown committed to a net-zero emission economy by 2045, although here too there remains ambiguity about the accounting methods allowed to reach this goal.

Emerging net-zero commitments in other countries. The columns show which greenhouse gases are covered, the net-zero year and the current status of the plan, as well as the approach to offsets and international aviation and shipping. Green indicates that all GHGs are covered, and marks an explicit aim to meet the target without using credits and to incorporate international aviation and shipping. Red indicates an explicit allowance for offsetting, or excluding aviation and shipping from the commitment. Amber indicates a lack of certainty. Source: graphic produced by CCC.

Meanwhile, France has a climate plan that would include a net-zero greenhouse gas target of 2050 and is working on a bill to come before its parliament in the spring. New Zealand is currently drafting a bill of its own, which may still include offsetting and exclude the most heavily polluting forms of transport.

The European Commission has proposed a net-zero target for 2050 that does not include any use of carbon credits, but also does not explicitly state the inclusion of aviation and shipping. This is not yet a legislative proposal, but has been supported by the European Parliament.

Other nations, ranging from Iceland to the Marshall Islands, have set mid-century net-zero targets in the strategy documents and nationally determined contributions (NDCs) they have submitted to the UN. However, such targets are not enshrined in law.

With uncertainty still swirling around many of these pledges, the CCC describes the net-zero target as an opportunity to cement the UK’s position as a “climate leader”. It would establish a clear pathway to total net-zero within an ambitious timeframe, which does not rely on carbon offsets and accounts for aviation and shipping.

This, they say, would be the latest in a long line of trend-setting commitments. With the Climate Change Act, launched just over a decade ago, the government established the world’s first legally binding, long-term emissions target.

Since then, the act has served as a model that other nations from Sweden to Mexico have followed in the creation of their own climate laws. The UK also trialled the first major emissions-trading scheme, and has consistently played a valuable role in international climate diplomacy, the committee says, providing climate finance and developing low-carbon technologies.

All this means that while the UK’s annual contribution to global emissions is now relatively small, the committee hopes that by making a net-zero pledge it will serve the additional benefit of inspiring other nations to follow suit. At a briefing on the new report, Stark said:

“This…would put [the UK] at the top of the pile. A genuine, really strong statement that net-zero can be achieved in a comprehensive way, and would make a really clear signal of leadership from the UK , similar to what we made in 2008 with the Climate Change Act itself.”

This leadership role is fitting, according to committee chair Lord Deben, who spoke of the UK’s historic responsibility for a large proportion of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere since it initially sparked the Industrial Revolution in the 18th century. (See Carbon Brief’s animation.) “But also we have an opportunity to lead the new industrial revolution, which will be based upon [a] sustainable economy,” he said.

How could the UK reach net-zero?

The net-zero target requires an economy-wide overhaul, the committee says. Although it says extensive plans are in place to meet current targets, the CCC’s new report concludes many of them either lack sufficient ambition or are not being implemented adequately.

Official figures show the government is on track to miss its existing climate targets from the late 2020s onwards. The committee says policies must, therefore, be “ramped up significantly” to meet this new challenge. This will mean most sectors reducing their emissions close to zero, without relying on offsetting or the mass removal of CO2 from the atmosphere.

In a net-zero UK, the electrification of sectors such as transport and heating would result in a doubling of electricity demand. Under the CCC’s projections, all of this power would need to be produced by low-carbon sources, which must quadruple their supply by 2050. Hydrogen would also need to tapped as a fuel for industrial processes, heating, HGVs and ships.

The report states the fledgling technology of carbon capture and storage (CCS) – which, as it stands, is not being implemented at scale in the UK at all – is “a necessity not an option”. Such measures will be required to mop up emissions from industry, to complement hydrogen and electricity production, and, with bioenergy crops, to remove CO2 from the atmosphere.

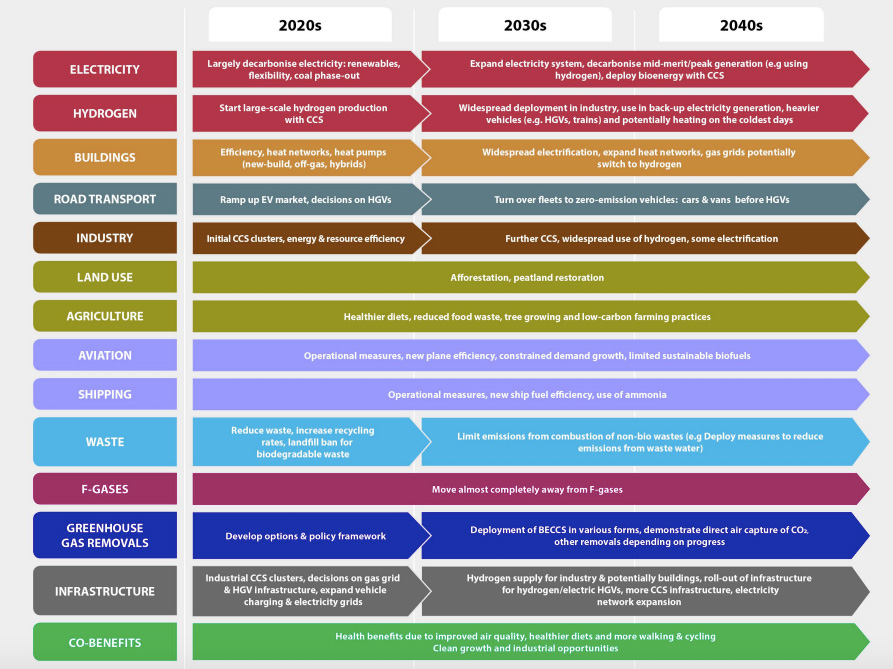

Breakdown of the contribution required by each sector to achieve net-zero greenhouse gases in the UK. Source: graphic produced by CCC.

To establish the full picture of how a net-zero economy could be achieved, the CCC began by analysing the “no-brainers”, says Thompson – strategies that could be implemented with relative ease and relatively low cost – and found this achieved a 77% reduction in emissions.

Thompson tells Carbon Brief that they proceeded to “push as hard as [we] realistically can” with their “further ambition” scenario, exploring all available measures, and found this approach achieved 96% reductions by 2050.

In order to achieve the full 100% reduction, the committee relied on the inclusion of a handful of “speculative” strategies. Compared with the electrification of cars, the success of these measures is less certain, but Stark notes they are still evidence-based and feasible.

“None of those are unicorns. These are all still things that we understand,” Stark tells Carbon Brief.

Thompson notes that while there is “no way that they will all come through”, they are sure that at least some of the options – which range from greater bioenergy rollout to synthetic fuels –will come into play in the coming decades. He tells Carbon Brief:

“We are comfortable that there are enough options there that enough will come through – and come through in a deliberate way at reasonable cost – that you will be able to close that 4% gap.”

This strategy means sectors that have previously gone untouched due to the perceived difficulty of decarbonising them, such as industry and aviation, have this time been targeted in the committee’s analysis. In the following sections, Carbon Brief explains what the CCC says will be required for each sector in the coming decades.

Net-zero goal: Electricity generation

In the scenarios laid out by the CCC, a large, reliable supply of electricity is vital to power everything from cars to heat systems. In its analysis, this is achieved primarily through an enormous rollout of offshore wind and other renewables, as the nation’s final coal plants are closed down.

The committee says the goal of increasing the supply of low-carbon power fourfold by 2050 will require “consistently strong deployment” of renewables. The report says this should be supported by nuclear and CCS plants, in which biomass or gas are burned and their emissions captured. It notes that an upcoming Energy White Paper should support this target.

Such deployment could include at least 75 gigawatts (GW) of offshore wind, compared to 8GW today and the 30GW covered by the sector deal made by the government for 2030. In practice, this would consist of up to 7,500 turbines covering up to 2% of the UK seabed. At present there are nearly 2,000 turbines in UK waters; however, each turbine will be larger in future.

At the same time, there will be a need to support this rapid electrification with measures that enhance flexibility, such as smart charging of vehicles and hybrid heat pumps. The CCC says these kinds of systems would help accommodate the greater proportion of variable power sources, such as wind and solar.

The CCC took a “cautious approach” in its projected scenarios, limiting the share of these variable renewable energy sources to 60%, thereby, ensuring a secure supply of electricity would be maintained. However, if – as some studies have suggested – this proportion could safely go higher, the system would be far cheaper than one in which nuclear and CCS had to be deployed more widely. As Thompson explains to Carbon Brief:

“This is another one of those cases where we think we have been conservative…We are pretty clear [in the technical report] that this is an assumption, not a recommendation. We think the renewables, wind and solar, are going to be the cheaper technologies, and the more we have of them the cheaper [it is] going to be.”

Though some forms of renewable power are starting to be deployed without government subsidies, the committee warns that for the time being intervention will still be required to secure the pace of expansion needed.

Measures required under the Core and Further Ambition scenarios in 2050. Source: graphic produced by CCC.

Net-zero goal: Homes

The CCC has previously flagged UK homes as insufficiently prepared for the challenges posed by climate change. Examining past efforts to improve the nation’s housing stock, its new report notes:

“Over 10 years after the Climate Change Act was passed, there is still no serious plan for decarbonising UK heating systems and no large-scale trials have begun for either heat pumps or hydrogen.”

Given this, it calls for an “overhaul” of the current strategy, with improvements to the heat efficiency of homes and a transition to hydrogen and electricity, all with the goal of totally decarbonising buildings by 2050.

The government’s Clean Growth Strategy already sets out the ambition to make decisions about low-carbon heating for gas-heated properties in the early 2020s. A glimmer of hope for such a strategy came in the recent Spring Statement, when chancellor Philip Hammond announced all new homes from 2025 will have what he called “world-leading” efficiency and low-carbon heating systems.

The committee says this commitment “is welcome and must be delivered in full”, but must be accompanied by an effort to transform existing houses as well – replacing gas boilers with heat pumps, heat networks and hydrogen boilers.

Suggesting large-scale deployment of such measures would have to start before 2030, the committee says “it would be regressive, and probably restrict progress, to pass the cost on fully to households”, highlighting this as a key focus for future funding reviews. However, the report also notes that engagement from households intent on reducing their carbon footprint will be “vital”.

The CCC emphasises that an energy efficiency retrofit of the 29m homes that already exist across the country must be a “national infrastructure priority”. It notes that straightforward improvements, such as insulation, draught proofing and new windows, reduce the rate of heat loss, and can come with energy savings that outweigh the costs.

Net-zero goals: Industry

Historically viewed as a difficult sector to decarbonise, the CCC says it has “significantly strengthened” its understanding of how to cut emissions from industry. This allows it to bring the sector in line with others.

Many of these gains will be based on the same principles applied in other sectors, such as the rollout of CCS, hydrogen and electrification. As Thompson tells Carbon Brief:

“If we are electrifying the vehicles on the road, we should be electrifying the vehicles off the road as well, if we are shifting boilers in homes and buildings to hydrogen, we can do the same with stationary heat sources in industry as well.”

The CCC notes that while these measures are not technically more expensive than analogous changes in other sectors, designing policies to make the necessary changes may be more challenging.

Like heating, it identifies industry as an area with costs that “cannot simply be passed on”. The report notes that while some of the costs may be paid by consumers, this will not work for “trade-exposed” industries that must maintain a level playing field to avoid their emissions simply being driven overseas – a phenomenon known as “offshoring”.

Pointing out that this “would not help to reduce global emissions, nor the UK economy”, the committee says the government can prevent “offshoring” and must design a framework to make the UK a leader in low-carbon goods:

“That could involve schemes similar to those in place today – free allocation of allowances within the EU ETS and compensation for costs resulting from UK climate policies. Alternatively it could involve taxpayer funding, new schemes such as border tariff adjustments or product and building standards that drive demand for low-carbon goods.”

Speaking to journalists at a pre-launch briefing, Deben reiterated earlier CCC analysis, which he said found “no evidence” that offshoring of industry from the UK had been driven by climate policy.

Net-zero goal: Road transport

Road transport is one of the key areas singled out by the CCC as not progressing fast enough in its decarbonisation. The report states the current government target of 2040 for a phaseout of petrol and diesel cars and vans is too late, and plans for delivery “are too vague”.

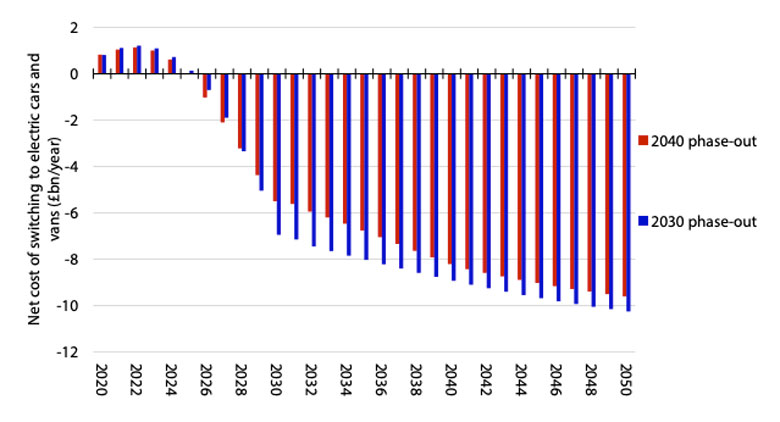

Electric cars are expected to be cheaper to purchase than conventional models by 2030, with considerably lower running costs. With this in mind, the committee notes that 2030 would be a desirable date for the sale of fossil fuel-powered vehicles to end, but suggests 2035 at the latest.

Overall, its analysis suggests electric vehicles will actually be cost-saving by 2030. This means an earlier 2030 switch would be cheaper for the UK economy as a whole, saving money relative to a 2040 end date.

A 2030 switch to electric vehicles would have more money than the 2040 switch currently planned. Costs are compared to continued use of petrol and diesel cars, and are the subsidy free total lifetime (14 years) costs relating to all new vehicles bought in that year. Includes upfront vehicle cost, refuelling cost (discounted at 3.5%), and costs of charging infrastructure, electricity generation and network expansion. To better represent vehicles available in the future the analysis assumes the costs and efficiencies of petrol and diesel cars also develop over time. As a result, these figures are not directly comparable to others in the report. Until 2028 costs are slightly higher for a 2030 phase-out date, which is largely due to electric vehicles being more expensive until this point and greater charging infrastructure requirements. Costs for a 2035 switchover date are not shown, but are slightly higher than for a 2030 switchover. Source: graphic produced by CCC.

It concludes the government must also support a strengthening of charging infrastructure. By 2030, 1,200 rapid chargers near major roads and a further 27,000 in towns across the nation will be required, it says, with even more installed in the decades that follow.

Besides these well-understood and ultimately cost-saving areas, the committee also considers the more ambitious goal of decarbonising HGVs. While it notes “the best solution is not yet clear” for these large vehicles, it says electrification, hydrogen or a combination of the two will help bring HGVs up to speed with other vehicles by the middle of the century.

Given the lag between a technology being developed and widely taken up within a sector, the committee concludes a decision will need to be made about the best path to HGV decarbonisation by the latter half of the 2020s.

Net-zero goal: Farming and land use

Central to the committee’s proposal are fundamental changes in the way British farmers use their land, with a far greater emphasis on carbon sequestration and biomass production.

Shifting to low-carbon farming practices, such as better soil and livestock management, would help cut emissions, but, according to the CCC, “would still leave agriculture as one of the biggest emitting sectors”.

Overall, their scenarios include a fifth of agricultural land being used to grow trees or energy crops, or else restored into peatland. It concludes such a transition could be made feasible by a country-wide switch to healthier diets and less food being wasted (see below).

The committee warns that a dramatic uptick in tree-planting will be required in order to remove sufficient quantities of emissions from the atmosphere by the middle of the century. While the government has set ambitious measures for this sector, it has fallen far short of what is required, as the report notes:

“Afforestation targets for 20,000 hectares per year across the UK nations…are not being delivered, with less than 10,000 hectares planted on average over the last five years. The voluntary approach that has been pursued so far for agriculture is not delivering reductions in emissions.”

The post-Brexit Agriculture Bill set out by environment secretary Michael Gove last year – and currently being considered in parliament – aims to reward farmers who provide “public goods” such as increased carbon sequestration.

The committee says by 2022 this bill should, therefore, be playing a vital role in not only promoting low-carbon farming, but also encouraging farmers to use their land to counteract greenhouse gas emissions.

Net-zero goal: Aviation and shipping

Aviation is still expected to produce more emissions than anything else in 2050, but the CCC identifies potential to limit emissions in this challenging sector. Together with shipping, the report concludes these international forms of transport simply “cannot be ignored” as every other sector is forced to cut its emissions close to zero.

In line with this, the report suggests both should be incorporated into the UK’s carbon budgets for the first time:

“The Climate Change Act (section 30) allows for emissions from international aviation and shipping to be included from any future year. Since the current carbon budgets have been set without these emissions, we recommend their inclusion from the first year of the sixth carbon budget (ie 2033).”

While not strictly included inside the existing carbon budgets, the CCC has always made an allowance for these sectors such that they are part of the UK’s overall target trajectory.

Cuts to plane emissions can come from improvements in fuel efficiency and switching to alternative fuels, according to the committee. However, as it stands, the committee says there are no commercially available, “low-carbon” planes, so the potential for these strategies is limited.

This means that even if there is a 10% uptake of “sustainable biofuel” by the middle of the century – as laid out in the most ambitious CCC scenario – aviation will still rely heavily on the removal of greenhouse gases from the atmosphere to achieve net-zero.

The report warns, however, that easier methods, such as planting trees, will not be enough to counterbalance aviation emissions. Instead the committee suggests more expensive measures, such as directly capturing CO2 from the air or bioenergy plants with CCS, will be required.

The CCC also notes a potentially significant role for constraining demand for flights, which is currently expected to continue growing rapidly in the coming decades.

For ships, the committee sees greater potential to cut emissions, with the possibility for virtually all vessels to be operating on zero-carbon liquid ammonia fuel by 2050.

Though the report does not address specific projects, such as the controversial third runway planned for Heathrow, it notes the committee will write again to the government this year “on its approach to aviation, building on the advice in this report”.

With these sectors still remaining some of the toughest to decarbonise, the report emphasises that if a net-zero target is agreed by the government, it must include them. Stark warned against ministers “cherry picking” from the committee’s advice, telling Carbon Brief this is something it would “come down hard on”.

Will lifestyles need to change for net-zero?

While the UK has made considerable progress towards cutting its emissions, this has largely been achieved through measures that have little impact on the day-to-day lives of British people. Coal power has largely been phased out and wind turbines have been erected, but there has been minimal pressure on the population to modify their behaviour to meet the nation’s carbon budgets.

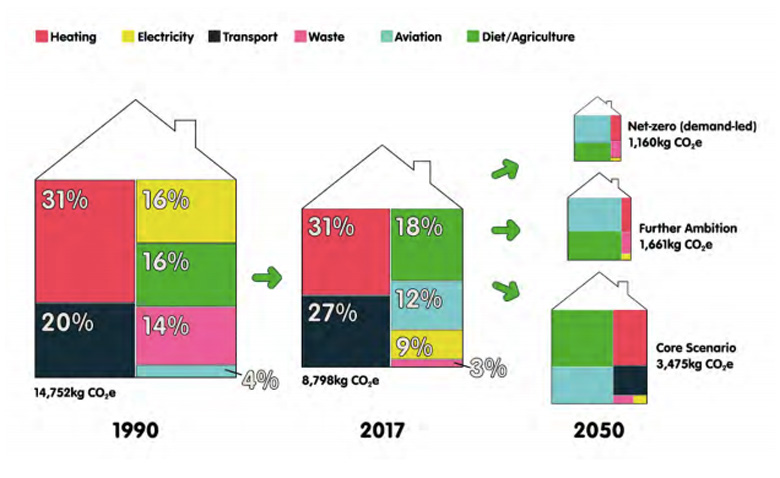

While the new CCC guidance does not call for a radical overhaul in the way people live, it does rely on a degree of behavioural change if the net-zero target is to be met. These changes will mainly affect the way people eat, fly and choose products.

Committee analysis suggests that while 38% of the shifts required will be wholly based on the uptake of low-carbon technologies or fuels, the rest will require at least some level of change in the way society or people operate. Of this, 9% of the changes must be made primarily in the way people behave.

The first main recommendation is a 20% reduction in the amount of carbon-intensive animal products – namely beef, lamb and dairy. They say these products could be replaced with pork, poultry, pulses and legumes, and note a low-meat diet can cut each individual’s emissions by 35% by reducing the impact of UK agriculture and freeing up land to store carbon or grow biomass.

Household emissions in 1990, 2017 and for different decarbonisation scenarios in 2050, including the reduction needed to reach net-zero. Source: Energy Systems Catapult (2019) Living Carbon-Free – Exploring what a net-zero target means for households.

While this may seem like a considerable demand, it is actually less than the scale of change laid out in the government’s own “EatWell Guide” for eating a healthier and more balanced diet. The CCC also notes the transition away from some animal products is already happening. Thompson tells Carbon Brief:

“We think a 20% reduction in beef, lamb, dairy that can be substituted by other meat products, by other protein sources, that’s not a major lifestyle change. That partly reflects that we are seeing it happen anyway, so we know the younger generations eat less meat than the older generations. We do need an acceleration in that shift, but that is the direction we are heading in already.”

Besides changing the contents of their fridge, the CCC also calls on households to further cut the carbon footprint of their food by eliminating waste. As it stands, 14% of the cost of a weekly shop goes on food that ends up in the bin.

The other major lifestyle change is for people to make an active choice to fly less. With the CCC predicting a 60% growth in demand for air travel by the middle of the century, Thompson notes that their advice is intended to curtail this surge rather than to cut demand overall.

In practice, this would mean individuals following the example of teenage climate activist Greta Thunberg and opting for train travel over short-haul flights, as well as reducing the number of long-distance flights they take. For those who continue to fly, the committee says airlines could add the cost of carbon offsets to the price of their plane tickets.

Further changes can come from adjustments in the way people purchase and use products, the CCC says. Some of this will fall on industry, but it will also be the responsibility of consumers to repair their possessions rather than replace them, or choose higher quality items. Thompson explains:

“You would need policies to do it, but you’re not requiring people to not have a washing machine, you’re just requiring them to choose one that will cost a bit more up front and lasts for longer – again, we don’t think that is a major lifestyle change.”

The CCC notes that while people can take immediate action to improve their diets or shift from driving cars to walking and cycling, all of these measures will require a degree of government input.

Stark tells Carbon Brief that even though not everyone needs to be a “climate advocate” to achieve such societal shifts, there will also be a need for far-reaching public engagement in changes that should ultimately yield considerable additional benefits.

The report also notes some behaviour changes with “significant barriers to public acceptability” in its “speculative options” section. These include a 50% cut in beef, lamb and dairy, and even fewer flights being taken – but they are not essential to the net-zero goal.

Does net-zero rely on negative emissions?

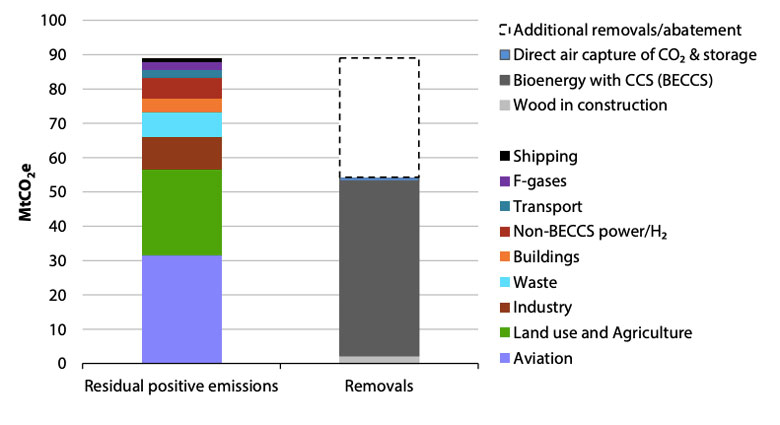

The CCC’s advice pushes for more action than ever before across all sectors, including those that are the hardest to decarbonise. However, even if this is achieved there will still be some emissions remaining, especially from aviation, agriculture and industry.

This means that beyond planting more trees, the committee also suggests the UK will need to develop a substantial negative emissions sector by 2050. In its advice, the remaining emissions are removed largely using bioenergy with carbon capture and storage (BECCS) – where crops are burned to produce power and the resulting CO2 is stored underground.

Comparatively small contributions (see figure below) could come from direct air capture of CO2 with CCS (DACCS) and a greater emphasis on wood as a construction material, which can effectively lock away CO2 from the atmosphere.

Sectoral emissions and contributions from removals presented for the Further Ambition scenario. The contribution from ‘additional removals/abatement’ refers to the options to go beyond the Further Ambition scenario and achieve net-zero emissions, which can be done with additional removals and/or further reductions of positive emissions. Source: graphic produced by CCC.

This is not the first time the committee has emphasised the importance of such technologies, which it previously said would be “central” to the global effort to meet the Paris targets. The CCC’s recommended path to meeting the existing 80% reduction target already relies heavily on them, which is why the committee describes CCS as a necessity, not a choice on the path to net-zero. As Thompson explains to Carbon Brief:

“In terms of our previous scenarios, we used to have about 50m tonnes of CO2 removals, largely from BECCS, and we’ve got just a little bit more than that now – between 50 and 60 I think…[So] the 100% scenario is not just 80% plus a load of removals.”

Instead, he says going beyond 80% is primarily reliant on doing “a hell of a lot more of everything”.

At the same time, the report points out that despite the committee’s past advice that CCS technologies are important to achieve deep emissions cuts, progress has been slow. As it stands there are 43 large-scale projects operating or being developed around the world, but none in the UK.

Previous CCC recommendations have stated the first “cluster” of CCS projects should be up and running by 2026, and the second by 2030. However, in its new advice the committee notes that “for a net-zero target it is very likely that more will be needed”, and should include some infrastructure focusing on the production of low-carbon hydrogen:

“The scenarios involve aggregate annual capture and storage of 75-175 MtCO2 in 2050, which would require a major CO2 transport and storage infrastructure servicing at least five clusters and with some CO2 transported by ships or heavy goods vehicles.”

The report notes that the government will need to take the lead to develop this new industry in the UK, with long-term contracts to reward plants that are capturing carbon and encourage further investment.

Is fracking compatible with a net-zero target?

Within the CCC’s guidance are plans to move away from gas, including switching the nation’s heating systems to run on hydrogen and electricity. However, even under the most demanding scenarios outlined by the committee, it sees a considerable quantity of gas being required in a net-zero economy.

This partly stems from what Thompson describes as the “cautious assumption” that variable renewables must be limited to 60% of the electricity mix. Shipping would also require gas if it is to transition away from high-polluting fuels, as would many sections of industry.

This is because under the CCC’s framework, ships would switch from oil to hydrogen-based ammonia fuel and industry would also require hydrogen to function. The committee based its analysis on the assumption this hydrogen would be produced by “reforming” gas in combination with CCS to avoid emissions.

While it is possible to produce hydrogen from water via electrolysis, Thompson says this would be more expensive – though he noted the committee had taken a conservative approach to this matter. He tells Carbon Brief:

“The scenario we have got is, if anything, a bit high on the side of gas, but maybe in reality you’d be using a bit less gas. If you did manage to do it with less gas you’d probably save cost in some instances – like in the electricity sector – and you’d certainly save a few tonnes here and there of residual emissions that come from CCS.”

Nevertheless, the continued need for at least some gas raises the question of whether fracking for shale gas can contribute to any of this demand in the long term for the UK. While the government says it supports the shale gas industry, developers have been plagued with controversy and are still a long way from contributing to the country’s energy system.

The CCC has been consistent in its guidance that fracking should only be allowed if it meets strict rules on emissions. In a briefing for journalists, Lord Deben said this was still the case in the new net-zero scenario:

“As far as fracking is concerned we have a very clear view – we have said that fracking is only acceptable under three very clear environmental requirements…It should not happen except under the very toughest environmental controls, it shouldn’t be additional to gas that we use in any case, and that we should in fact ensure that we don’t build a kind of infrastructure that means way after the point at which we should have stopped using gas, we claim we have to because we built this infrastructure.”

What are the costs and benefits of net-zero?

The CCC says the UK can cut its emissions to net-zero by 2050 at a “manageable” cost, equivalent to 1-2% of GDP each year. “There will also be large benefits” to set against these costs, the CCC says, including a reduced contribution to climate damages and cleaner air.

Importantly, this 1-2% cost is the amount that would need to be invested in the transition to net-zero rather than an estimate of any impact it might have on the overall size of the UK economy.

Moreover, due to the rapid recent cost reductions seen for key low-carbon technologies such as renewables and batteries, this 1-2% range is the same as previously expected for a 80% goal. This level of cost was accepted by parliament when it backed that 80% target.

“I don’t see those costs as a huge imposition on the UK economy, certainly not in comparison to, for example, capital investment expenditure each year of about 20%,” Stark tells Carbon Brief. “We’re being transparent about these costs and making the point that they’re worth incurring…But we don’t want to whitewash the cost or the scale of the challenge.”

The committee recommends that the Treasury carry out a review of how these costs would be funded and where would fall. It says:

“The review should cover the use of fiscal levers and exchequer revenue, costs from carbon trading schemes, the impact on energy bill-payers and motorists, and the costs to industries especially where they are carbon-intensive and trade-exposed.”

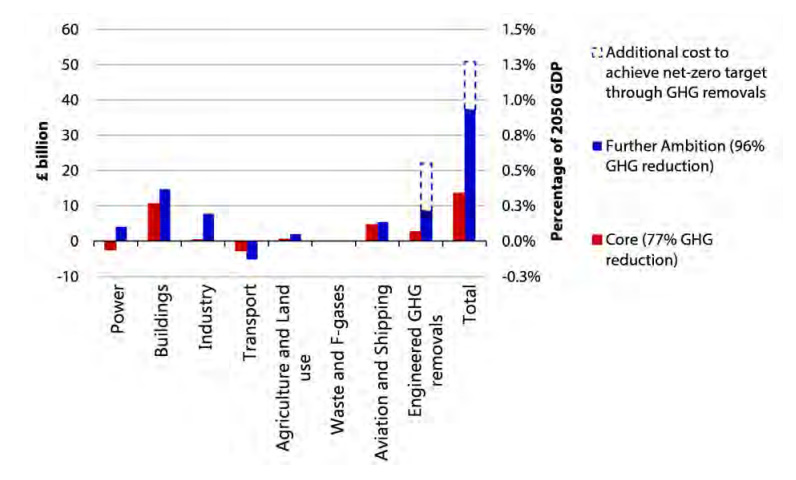

The chart below shows the CCC’s current estimate of how the costs of net-zero would be distributed between different sectors of the UK economy.

For each sector, the red column shows the costs of meeting the “core” scenario of a 77% overall cut in emissions. The blue column shows the cost to raise this to a 96% cut and the dashed total columns show potential investments needed in additional carbon removal technology.

Left axis: Annual investment costs of meeting the net-zero 2050 target, broken down by sector. The right axis shows the costs as a percentage of GDP in 2050. Source: graphic produced by CCC.

The chart above also shows clearly how costs are concentrated in buildings, industry, aviation and shipping, as well as in the provision of emissions removal technologies.

Notably, transport would see net savings in the transition to net-zero, the CCC analysis suggests, as it expects electric vehicles to have lower upfront and lifetime running costs in roughly a decade.

These savings, and others, could completely offset the increase in household bills due to low-carbon heating, the CCC says. This is shown in the chart, below, where transport savings (green) combine with other changes towards a net-zero goal, to offset higher heating costs (red).

Changes in household expenditure as a result of the transition to net-zero, in £bn per year. Reading from left to right, the chart begins with base costs for high-carbon heating and shows the increases needed for a low-carbon switch. This is followed by savings due to energy efficiency, power and transport. Source: graphic produced by CCC.

The CCC advice explains why it has focused on the investment costs to reach net-zero, rather than attempting to calculate the overall economic impacts for the UK.

Some of the models used for such estimates suggest net-zero would cause the UK to have a smaller economy than otherwise, while others show it would increase GDP, the CCC says. These differences largely depend on the economic school of thought followed by the model’s developers.

The report says:

“We do not take a view on the merits of different models or economic schools of thought. However, whether positive or negative, models tend to agree that the economic impacts of low-carbon scenarios are a few percentage points of GDP – in the same range as our resource cost estimates.”

Beyond pure economic calculus, the CCC emphasises the wider benefits of a net-zero goal. These include improved quality of life due to cleaner air and healthier diets, lower risks from climate change and the potential for industrial opportunities if the UK is an “early mover” in the shift to net-zero.

What happens next?

Now that the CCC has delivered its advice, it is up to the governments in Westminster, Cardiff and Edinburgh to respond. According to the CCC, this response must include not only the adoption of a net-zero goal but also the implementation of stronger policies to deliver that target.

At the UK level, adopting a net-zero target for 2050 would require “secondary legislation” amending the existing 80% goal to 100%. The Act gives ministers the power to draft such legislation, which would be subject only to affirmative votes in both houses of parliament.

In legislative terms, this makes the CCC’s advice much simpler to adopt than if it had called for separate targets for CO2 and other greenhouse gases – or if it had recommended a different target year than 2050. (Thompson tells Carbon Brief this is “absolutely not” why 2050 was selected.)

Under an emailed statement from secretary of state Greg Clark, the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) says: “We are not immediately accepting the recommendations…but will be responding in due course.”

In the statement, Clark says:

“To continue the UK’s global leadership we asked the CCC to advise the government on how and when we could achieve net zero. This report now sets us on a path to become the first major economy to legislate to end our contribution to global warming entirely.”

Meanwhile, an emailed statement from the Scottish government says it has already “lodged [an amendment] to set a legally binding target of net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2045 at the latest”. Scottish climate change secretary Roseanna Cunningham says in the statement:

“There is a global climate emergency and people across Scotland have been calling, rightly, for more ambition to tackle it and safeguard our planet for future generations. Having received independent, expert advice that even higher targets are now possible, and given the urgency required on this issue, I have acted immediately to set a target for net-zero greenhouse gas emissions for 2045.”

The committee’s advice has arrived at a time of heightened attention on climate change, with public support for action running high and a near-unprecedented media focus on the subject.

Animation: Mentions of "climate change" in UK media over past decade.

April 2019 at near-record levels due to coverage of @ExtinctionR protests, @GretaThunberg visit and @BBCOne Attenborough film.

Only surpassed – just – by Dec 2009 when COP15 summit took place in Copenhagen. pic.twitter.com/2gCK8usYrf

— Carbon Brief (@CarbonBrief) May 1, 2019

A cross-party group of 191 MPs and 53 Lords have already signalled their support for a net-zero target for the UK and there is little else being legislated in parliament due to the Brexit deadlock.

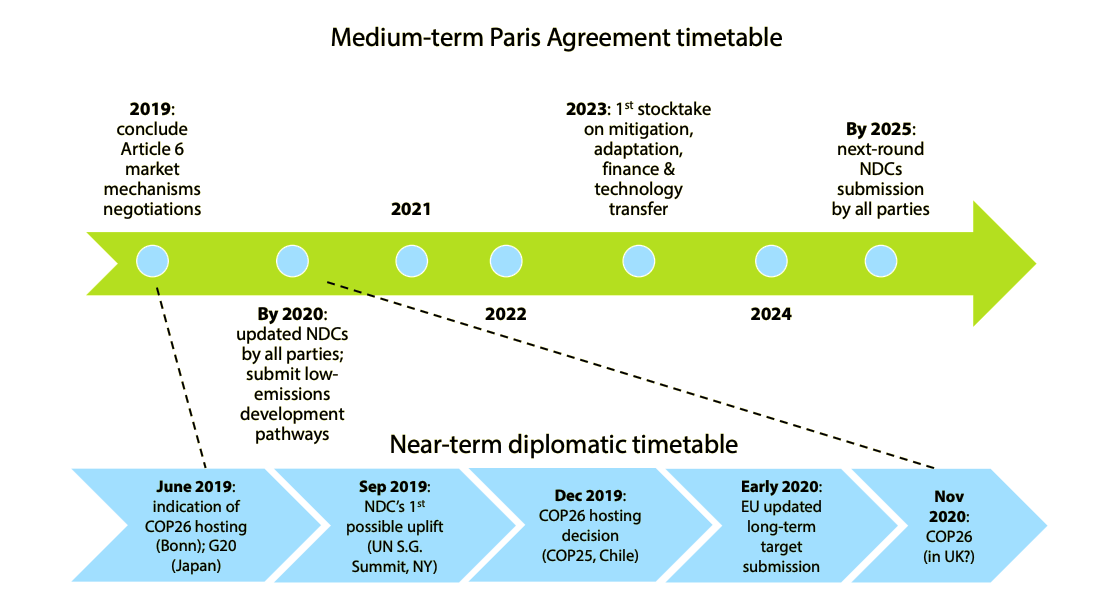

There are also international political reasons for the UK to adopt the recommended goal, having signalled its wish to host the COP26 UN climate talks next year. A decision on the COP26 venue is due later in 2019, as shown in the timeline, below.

Timeline for the global “ratchet”, whereby nations increase the ambition of their pledges (“NDCs”) under the Paris Agreement on climate change. “Article 6” refers to market mechanisms under the Paris deal, such as carbon trading. See Carbon Brief’s summary of the COP24 climate talks in Poland for more details of this and other terms in the timeline above. Source: graphic produced by CCC.

As well as raising its 2050 target to lead by example, the UK should use its influence to promote international climate efforts, the committee’s advisory group says. This should include, among other priorities: shifting investments away from high-carbon infrastructure, “mainstream[ing]” climate into foreign and security policy; and “leading the way” on sustainable finance.

Asked by Carbon Brief if the government might score a political win by adopting a net-zero target without the policies to match, CCC chair Lord Deben told a pre-launch media briefing that he did not think the government would “get away with not delivering”. Referring to the current political and media landscape around climate change, he said: “I think the world has changed, don’t you?”

Finally, Stark tells Carbon Brief the committee “reserves the right” to revisit the fourth and fifth carbon budgets next year, when it gives its advice on the sixth budget for 2033-2038. The CCC report says:

“We do not recommend changes to the fourth or fifth carbon budgets at this time, but note that both were set on the path to the existing 80% target and therefore are likely to be too loose.”

In the letter requesting the CCC’s advice, the government had sought to mark these earlier carbon budgets as “out of scope”. Stark tells Carbon Brief that this concern is misplaced:

“My point to [climate minister] Claire Perry would be that the answer to the problem you have at the moment – with, particularly, [meeting] the fifth carbon budget – is not a real problem, because you will quickly be on a different trajectory if you accept the advice on net-zero…This is a phantom issue that is gripping Whitehall at the moment.”

-

In-depth Q&A: The UK should reach ‘net-zero’ climate goal by 2050, says CCC