In-depth Q&A: Will China’s emissions trading scheme help tackle climate change?

Hongqiao Liu

06.24.21Hongqiao Liu

24.06.2021 | 2:32pmAfter a decade of preparation, China’s national emissions trading scheme (ETS) officially enters the operational phase in 2021.

The trading formally started on 16 July, with an opening price of 48 yuan ($7.4) per tonne of CO2.

Despite only including the power sector in its initial phase this year, it is already the world’s largest ETS, overtaking the European Union’s ETS and covering 12% of global carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions.

China’s leadership has high expectations for the trading system. They hope it can help the nation accelerate its energy transition at “lower cost” on the way to achieving its “dual carbon” climate goals of peaking emissions by 2030 and reaching “carbon neutrality” by 2060.

But a “benchmark”-based design, limited coverage and the lack of a firm cap on emissions raise question marks over whether the ETS, in its current form, will help China achieve its climate goals.

Carbon Brief has taken a deep dive into the new scheme by analysing government documents and speaking to a wide range of experts.

This in-depth Q&A aims to answer some of the most pressing questions about China’s ETS and what it means for tackling climate change.

- Why is China introducing a national emissions trading scheme?

- How will China’s ETS work?

- What is covered by China’s ETS?

- What will be required under the ETS?

- How will ETS permits be allocated?

- What does the ETS mean for the power sector?

- Will the ETS cut emissions?

- When will the ETS be expanded?

- Will China put a cap on ETS emissions?

- What will happen to China’s pilot ETSs?

- What comes next for China’s ETS?

Why is China introducing a national emissions trading scheme?

China is currently the world’s largest emitter of greenhouse gases, accounting for more than a quarter of the global total in 2019, according to US thinktank the Rhodium Group.

Its emissions are dominated by the power sector and manufacturing, with electricity (40%) and industry (29%) alone making up more than two-thirds of the nation’s total.

Since 2010, China has been saying it would introduce an ETS to help regulate these emissions. In 2015, China confirmed its firm commitment to do so.

Put simply, an ETS is a way to put a price on carbon. Designated CO2-emitting sites, such as factories or power plants, are given the right to release a certain amount of carbon in the form of “permits” or “allowances”, which can be traded. At the end of each cycle, participants must submit permits equal to their actual emissions.

Over the intervening years, the launch of China’s ETS has been repeatedly delayed. A deadline of “within the 12th five-year plan period” (2011-2015) was postponed to 2016, then to 2017.

A “three-phase development plan” for 2017-2019 anticipated a “rapid operation phase with maturity” and an ETS that would “play a central role in greenhouse gas emissions control” by 2019.

The launch was later delayed again to 2021.

Stian Reklev, Beijing-based director of Carbon Pulse, a news and intelligence website focused on carbon markets, tells Carbon Brief that the challenge of collecting reliable emissions data, “political infighting” and a government reshuffle in 2018 are the principal reasons for the delays.

He suspects the initial market design, prepared by mid-level government officials, was considered too ambitious and “got watered-down” by higher-level officials in the State Council and those from other ministries, who are concerned more with the “overall shape of the economy”.

Along the way, China launched a series of ETS pilots (see Carbon Brief’s 2018 article) and also continuously adjusted the design, policy framework and regulatory authority for the national scheme.

Then, in September 2020, China’s president Xi Jinping announced a new target to reach carbon neutrality by 2060. And, in December 2020, he reaffirmed China’s “Nationally Determined Contribution” (NDC) commitment to peak its carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions “as soon as possible before 2030”.

This lent new significance to the national ETS, with Xi repeatedly referring to the scheme in the context of achieving his nation’s “dual carbon” goals for 2030 and 2060.

The first annual “implementation cycle” of China’s national ETS kicked off on 1 January 2021 and online trading of emissions permits is due to begin by the end of June.

Reporting the news of its opening in January, Xinwen Lianbo, a prime time news programme aired by state broadcaster CCTV, emphasised the significance of the national ETS starting to operate.

The daily news show is one of the most important mouthpieces of the Communist Party of China (CPC). The programme said:

“It is the first time that China has pressed the responsibility of controlling greenhouse gas emissions onto enterprises from the national level and promoted the upgrading of industrial technology through a market-pushing mechanism.”

Crucially, China’s ETS will not operate in the same way as other “cap-and-trade” schemes, which use a declining “cap” to ensure CO2 emissions fall each year. (See: How will China’s ETS work?).

In the first implementation cycle, permits will be given for free, based on the output of each site and “benchmarks” of emissions per unit of output, as well as other adjustments. (See: How will ETS permits be allocated?).

In general, the current design means a regulated power plant will receive more permits if it generates more electricity.

As a result, the ETS should – in theory, at least – encourage more efficient operations, but it is not guaranteed to reduce emissions overall. (See: Will the ETS cut emissions?).

The scheme could be tightened in the future by adjusting the benchmarks over time, or by introducing an absolute cap on the emissions that can be released under the ETS.

The regulatory and legislative structure underpinning the ETS is relatively weak and fines for breaches are low, but these too could be strengthened over time. (See: What comes next for China’s ETS?).

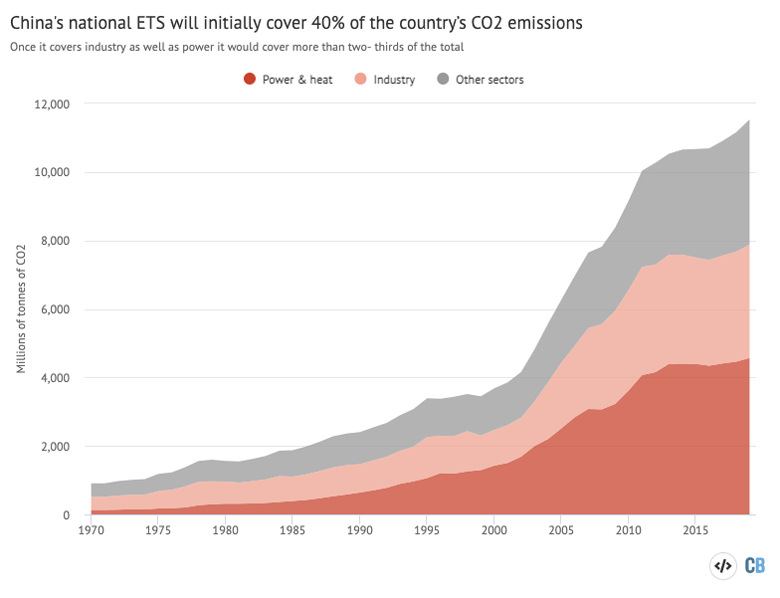

Initially, it only covers the electricity generation sector and “captive” power plants that directly serve industrial sites, but this still amounts to nearly nearly 40% of China’s CO2 emissions, as shown in the chart below (red). This alone amounts to around 15% of global CO2 emissions.

The ETS is expected to expand to other sectors later, which would bring 72% of China’s carbon emissions into the scheme (See: When will the ETS be expanded?).

China’s national ETS is already the world’s largest, eclipsing the EU ETS and nearly doubling the share of global emissions covered by carbon trading from 9 to 17%.

The initial phase is a compromise, designed to ensure buy-in and avoid conflict, says Chen Zhibin, a senior consultant at Sino-Carbon Innovation & Investment, a Beijing-based private consulting firm.

There has been widespread concern that if the national ETS were to advance too aggressively, Chen explains, then leading companies from the industrial sectors might boycott it and refuse to comply.

He adds: “Today’s market design is a relatively safe solution. It’s a result of years of negotiation between regulators, industry associations and big enterprises.”

How will China’s ETS work?

In principle, China’s national ETS has no fundamental differences from similar schemes elsewhere. However, it carries “Chinese characteristics” that mean it will operate in a very different way.

Like other ETSs, it is a market-based, carbon-pricing scheme created by the government, with the goal of efficiently and cost-effectively managing the greenhouse gas emissions it regulates.

Unlike other ETSs, however, the Chinese scheme does not currently put a fixed cap on emissions, nor promises a declining cap over time. Therefore, it is not guaranteed to cut carbon. (See: Will China put a cap on ETS emissions?)

In the current design, China’s ETS has a flexible emissions cap that can go up or down from year to year, depending on the output of the regulated sites – for example, power plants.

Under the flexible cap, each site receives a “verified allowance”. This is the number of permits equal to the amount of CO2 the site is allowed to emit.

Put simply, the allowances are calculated based on two factors: the site’s output – electricity generation or heat supply – and the corresponding intensity benchmark.

The benchmarks are measured in terms of emissions per unit of output and vary according to the type and size of the site. (See: How will ETS permits be allocated?).

This gives sites an incentive to outperform their benchmark by running more efficiently. However, allowances are also subject to adjustments, including a bonus for sites that operate infrequently, which could counteract the efficiency incentive.

Finally, the flexible cap is calculated as the sum of verified allowances for all regulated sites. The complexity of this process and the lack of a firm cap makes it unclear if the ETS will cut emissions, under its current design, in the short term.

The price of carbon within China’s ETS is also uncertain, for similar reasons. Stakeholders expect the average price to start at 49 yuan ($7.6) per tonne of CO2, according to China Carbon Forum, an independent platform focusing on fostering climate actions in China.

This $7.6/tCO2 estimate would put prices at more than twice the average in China’s ETS pilots and similar to levels on the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI) market in the eastern US states, but much lower than the $60+ levels on the EU ETS.

For now, sites regulated by China’s ETS will be given permits equal to their verified allowance for free. Sites can then buy or sell permits in the ETS, as well as purchase China Certified Emissions Reduction (CCER) certificates in a complimentary market to offset their emissions.

(The current interim administrative measures and the draft interim ETS regulation leave open the possibility of a proportion of permits being sold at auction in the future.)

At the end of each cycle, regulated sites must legally hand over (“surrender”) a number of permits equal to their “verified emissions” to demonstrate compliance with the ETS. This means that measuring, reporting and verifying emissions is key.

The ETS operates on an annual cycle of compliance, including deadlines for the reporting of emissions and the submission of permits. (See: What will be required under the ETS?).

One of the most criticised shortcomings of the current scheme is the limited penalty for non-compliance or forged information, with maximum fines of just 30,000 yuan ($4,605).

Dr Zhang Shuwei, director of the Beijing-based Draworld Environment Research Center, said in an interview with Caixin Media in January 2021 that this effectively “caps the cost of carbon” on the ETS, because companies can “compare the cost of compliance with paying for the penalty”.

Li Lina, senior manager at adelphi, a Berlin-based independent think tank and public policy consultancy on climate, environment and development, says the current design of the national ETS features “no hard cap”. It also has “limited compliance obligations” and “relatively low compliance measures”, she adds.

Nevertheless, the scheme does ensure the start of nationwide carbon pricing, with the potential for expansion and tightening later on. She tells Carbon Brief:

“At its very beginning, the aim is to ensure all companies buy into the idea of carbon pricing. Traditionally, many covered entities consider carbon pricing instruments as an additional cost imposed by the state rather than an opportunity to generate extra revenues from trading in the market.”

What is covered by China’s ETS?

When China and the US issued their joint statement ahead of the Paris COP21 in 2015, China said its ETS would cover “power generation, steel, cement and other key industrial sectors”.

By January 2016, a total of eight sectors had been nominated as the first batch set to be covered by the upcoming national carbon market, accounting for 50% of China’s total emissions.

The nominated sectors were petrochemical, chemical, building materials including cement, steel, non-ferrous metals, pulp and paper, power generation and aviation.

However, these ambitions were soon scaled back to just three sectors in May 2017 and later downsized again to just one, namely power and heat generation, accounting for 40% of China’s emissions. (The ETS will also cover “captive” power plants that supply industrial sites.)

This means that in its first cycle in 2021, the scheme will cover 4,000m tonnes of CO2 (MtCO2), equivalent to one-seventh of global CO2 emissions from fossil-fuel combustion. (This figure has been cited by officials for some years; more recent data suggest it is in the region of 4,500MtCO2.)

The number of sites covered by the ETS has also fallen. Official estimates fell from “over 10,000” to “7,000-8,000” and eventually just 2,225 in the initial phase.

These sites, which were listed in a December 2020 release from the Ministry of Ecology and Environment (MEE), have set up their trading accounts, according to state-affiliated China Securities Daily.

The threshold for inclusion in the ETS is currently set at 26,000 tonnes of CO2 equivalent (CO2e) per year per “entity”. This is roughly equivalent to the annual emissions of a small five megawatt (MW) coal-fired power plant.

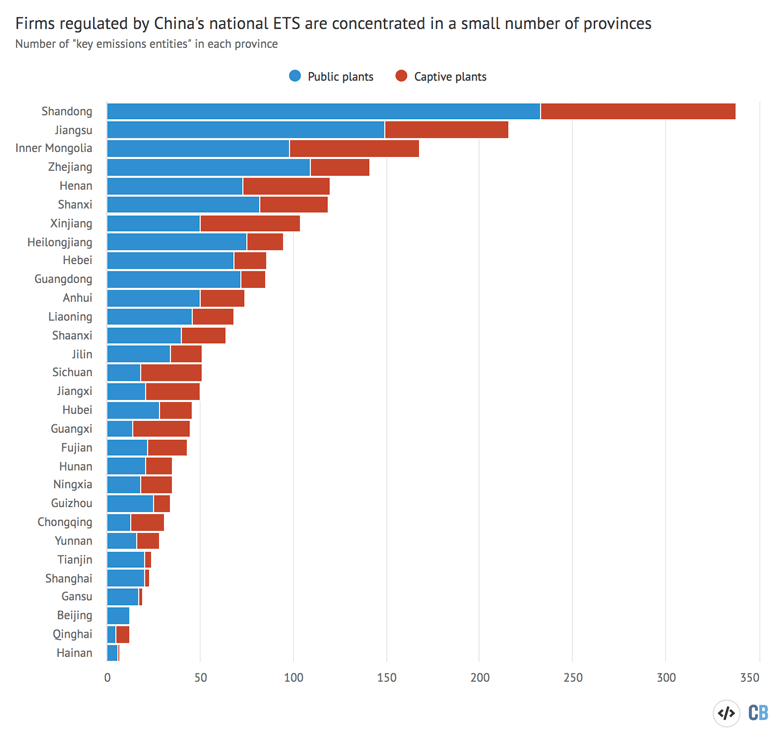

According to MEE’s ETS allocation plan, the 2,225 initial participants – described as “key emission entities” – were selected based on their greenhouse gases emissions in 2013-2018, as collected, verified and compiled by MEE’s provincial subsidiaries.

Although the interim administration measures specify that the operation of the ETS should be subject to disclosure requirements, there is limited public information available.

Published details regarding the 2,225 ETS sites are limited to the name of the company, the provincial location and a “Unified Social Credit Identifier” (USCI), which is a unique 18-digit code used to identify business registration and taxpayers in China.

Carbon Brief analysis of this information reveals the business activities and fossil fuel types for each participant. It also reveals whether they generate electricity for wider consumption or whether they are “captive power plants”, namely, supplying heat and electricity directly to industrial sites.

(See the Methodology for this analysis at the end of the article.)

The chart below shows that regulated firms are relatively concentrated, with a third found in just three provinces – Shandong, Jiangsu and Inner Mongolia – and 70% in the top ten provinces.

Carbon Brief’s analysis shows that nearly 98% of the sites regulated by the first implementation cycle of the ETS in 2021 are operating at least one coal-fired power unit, with gas fuelling the remainder.

The majority of coal-fuelled sites rely on “conventional coal” – regular thermal coal such as bituminous coal, lignite and anthracite – with their allocation of free permits dependent on the size of the plants and adjustments for running hours. (See below.)

Half of the sites using “unconventional coal” – coal wastes, including mixed fuels with biowaste – are located in two provinces, namely Shanxi and Shandong. These sites receive more generous benchmarks under the ETS, meaning more free permits.

Notably, many of the provinces with a high concentration of regulated coal power firms have a poor record in terms of meeting their targets related to environment and energy.

For example, in early February 2021, the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC), which is China’s central economic planner, criticised Inner Mongolia for failing to meet its “dual-control” targets on energy consumption and energy intensity.

In the same February release, the NDRC also named Anhui and Shandong for increasing their coal use, whereas their targets require a reduction.

The national ETS covers only a small number of gas-fired power sites, 70% of which are in three developed regions, namely Jiangsu, Guangdong and Beijing.

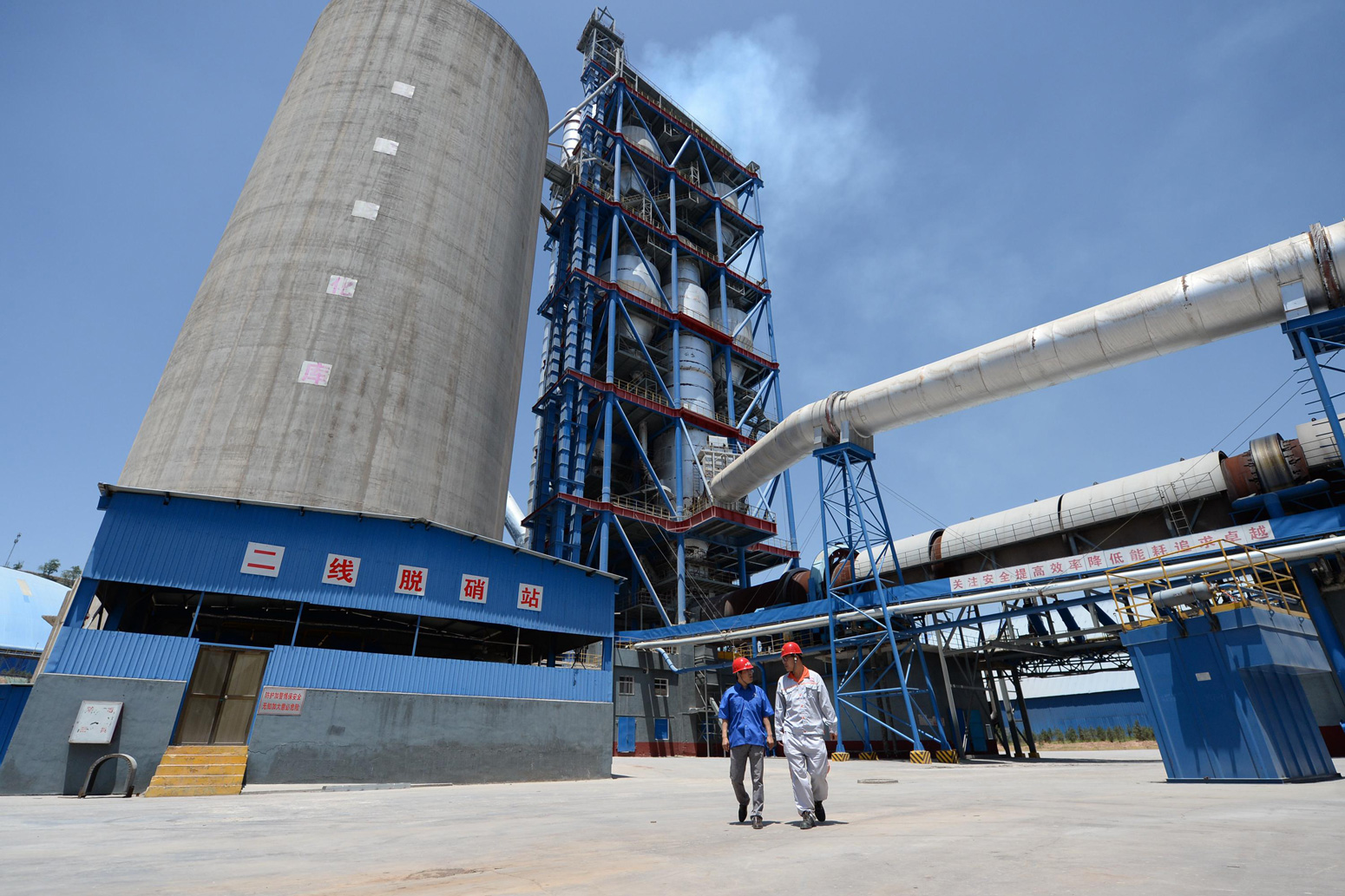

Although the ETS currently only covers the power sector, industrial sites from a variety of other sectors will be indirectly affected as a result of their “captive power plants”.

These plants are also known as “self-use power plants” and are built to provide stable power supplies, with lower energy costs, for the private use of industrial or commercial sites.

According to Global Energy Monitor (GEM), as of January 2021, there was 132 gigawatts (GW) of captive coal capacity in operation in China, accounting for 13% of the total for coal power overall.

The GEM data shows that 85% of the captive capacity was found in three industrial sectors: aluminium; iron and steel; and a broader category listed as “other mining and metals”.

Whereas captive plants account for a relatively small share of China’s overall coal capacity, Carbon Brief analysis suggests there are 770 regulated by the ETS, accounting for more than a third of the 2,225 sites in its first implementation cycle.

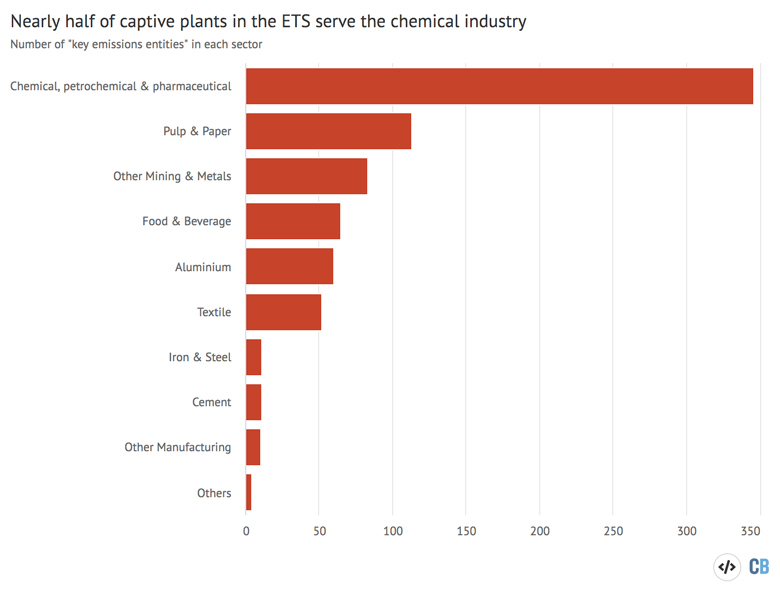

Nearly half of these captive plants serve the chemical industry, with others covering a wide range of industrial sectors, as shown in the chart below.

Carbon Brief’s analysis shows that 45% of the captive plants supply heat and power to chemical, petrochemical and pharmaceutical companies, with another 15% supplying pulp and papermaking.

This is also in contrast to the split of captive capacity identified by the GEM coal tracker, where metal industries accounted for most of the total.

Aiqun Yu, China researcher from GEM, says the divergence may result from the type and size of the captive power plants covered by GEM’s dataset, plus the China ETS’s list of “key emission entities”.

She tells Carbon Brief that captive power plants mostly provide electricity for aluminium production, while mostly steam and heat for other sectors, such as petrochemical and textile. In practice, the plants for heat are usually smaller in capacity than the power plants.

In addition, the ETS covers some small-scale captive plants fueled by gas or waste gas and heat, which the GEM doesn’t cover.

The other captive plants regulated by the ETS supply a range of manufacturing industries, such as food and beverage, aluminium, textile, iron and steel, cement and “other mining and metals”.

Many of these sectors are regulated in China as “energy-intensive, high-polluting, high-emission and resource-intensive industries” due to their environmental impacts.

When China declared a “war on air pollution” in 2013, captive plants were flagged for their smoky chimneys: new construction was prohibited in key pollution control areas, such as Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei, and existing sites faced mandatory fuel-switching from coal to gas.

In 2015, the NDRC and the National Energy Administration (NEA) issued a joint guideline, attempting to phase out the most polluting captive power plants and apply “equal management” to them as on public power plants.

The same year, the two authorities stated that many captive power plants were “constructed before approval”, were of lower efficiency with higher pollution discharges, and were loosely managed with unreliable performance.

However, these instructions were not fully implemented and, consequently, the extensive expansion of captive plants has continued.

The Central Ecological and Environment Inspection Team (CEEIT) criticised the phenomenon at provincial and national scale, blaming captive plants for the overshooting of China’s “coal consumption cap” and increased local air pollution.

For example, Shandong saw a “spurt of growth” in 2013-2017, with 110 new captive power generation units illegally constructed. Their installed capacity exceeded 26GW – equivalent to one-quarter of the total installed capacity of captive power plants nationwide in 2014.

In Shandong, around 88% of the captive power units accused of violating regulations were built by two single aluminium manufacturers. In terms of the installed capacity, nearly two-thirds came from Weiqiao Pioneering Group, one of the largest aluminium producers in the world, and the rest from Xinfa Group.

Attempts to clean up and upgrade captive power plants continue today. In 2020 alone, Shandong shut down 28 captive power units and upgraded another ten. Still, at least 105 captive power plants from Shandong have emissions sufficient to be covered by the national ETS.

“It’s been very difficult to push for the phase-out of the inefficient captive coal-fired power plants,” says Chen Zhibin from Sino-Carbon. “It seems carbon pricing could be an efficient approach to solve the problem.”

Adelphi’s Li Lina tells Carbon Brief that, as a matter of “fair play”, the power sector had also been lobbying for including captive coal-fired power plants in the carbon market.

But setting benchmarks for both public and captive power plants is “a really tricky one”, according to Beijing-based Huw Slater, lead specialist on climate at international consultancy ICF. He tells Carbon Brief:

“In a carbon market that would disincentivise inefficient captive power plants using a single industry-wide benchmark, phasing out the plants also means pricing out the industrial operations that they support. Depending on the importance of the industry to the local economy, this may not be desirable.”

What will be required under the ETS?

China’s national ETS comes with a series of requirements that go beyond the simple buying and selling of allowances between regulated sites.

All regulated entities in the initial phase, which covers the power sector and captive power plants, are subject to monitoring, reporting and verification (MRV) of their emissions in 2019 and 2020.

Importantly, however, MRV for emissions in 2020 is also required from sites whose annual emissions are above the 26,000tCO2 threshold in the seven other sectors that were originally nominated for inclusion within the ETS, namely, petrochemical, chemical, building materials, steel, non-ferrous, paper and pulp, power and aviation.

These sectors could be covered by an expanded ETS at a later date and must already start tracking and reporting their emissions. (See: When will the ETS be expanded?)

Despite the lengthy buildup to its launch, many of the details of the operation and requirements under the ETS have been released at the last minute.

For example, China aims to start online trading of allowances by the end of June 2021 and complete the first implementation cycle on 31 December 2021.

But the government body responsible for the regulation and operation of the ETS – the MEE – is still completing and testing the infrastructure required to start trading.

When interviewed by Carbon Brief in March, Carbon Pulse’s Stian Reklev said the trading platform, based at the Shanghai Environment and Energy Exchange, and the registry of participants held in Hubei, had “not been finalised”.

However, the trading platform launched “trial runs” in late May and the registry system went on to pass the “technical acceptance test” in early June.

Reklev adds, though, that once trading starts sites will have half a year to trade emission permits back and forth in the market, before the first compliance deadline in December.

Details on MRV also arrived late. At the end of March, the MEE released a batch of three ETS-related policy documents, including an interim guideline on MRV and a notice on MRV-related work in 2021, in addition to a revised draft of an interim regulation on carbon emissions trading.

These documents revealed a more detailed timetable for the first implementation cycle, shown in the table, below. The table below sets out the various steps the MEE has required relevant Chinese sites to take in order to monitor, report and verify their emissions and their corresponding deadlines.

| Deadline | Monitoring, reporting and verification (MRV) | Emission permits |

|---|---|---|

| 30 March 2021 | Pre-allocation: All 2,225 regulated power generation sites received their preliminary allocation of emission permits for 2019 and 2020, and opened a trading account in the Shanghai Environment and Energy Exchange. | |

| 30 April 2021 | Reporting: Power generation sites complete the online reporting of emissions in 2020. | |

| 30 June 2021 | Verification: The power sector completes verification on the GHG emissions in 2020 and reports the results to the MEE. Confirmation of coverage: MEE’s provincial subsidiaries submit a list of regulated sites in the power generation sector. | |

| From end of June 2021 | Online trading starts for the power generation sector. | |

| 30 September 2021 | Reporting: All other seven selected sectors complete the online reporting of GHG emissions in 2020. | Allocation: MEE completes the verification and makes final allocations of emission permits for the power generation sector in 2019 and 2020. |

| 31 December 2021 | Verification: All other seven selected sectors complete the verification on the GHG emissions in 2020 and report to the MEE. | Compliance deadline of the first implementation cycle: Regulated power generation sites surrender permits covering their emissions in 2019 and 2020. |

For the first implementation cycle in 2021, the power generation sector – including captive plants – is expected to surrender allowances for the previous two years.

However, this is not necessarily a problem, according to several experts interviewed by Carbon Brief. In practice, the power sector has been carrying out MRV since the NDRC – the then-authority in charge of climate change including the ETS – announced the latest development plan for the national ETS in December 2017.

The management rules on registration, trading and settlement of the national ETS only became clear in mid-May, just a month ahead of the announced date for trading to start.

Additionally, some details about how the market will operate have been released by state-affiliated media before being formally published . For example, in late May, China Securities Times first revealed that the national ETS would introduce a price stability mechanism to limit the daily price swing to within 10%, before the information was confirmed by a formal notice of the trading platform a month later.

According to “industry insiders” cited by the state-affiliated China National Radio, the volume of allowances traded in the national carbon market in 2021 is expected to reach 2,500MtCO2, with trades hitting a total value of 6bn yuan ($925m).

This means that the volume of trading would be three times the equivalent of all eight Chinese ETS pilots combined in 2020, representing a significant increase in activity.

How will ETS permits be allocated?

Sites regulated by China’s national ETS are given (“allocated”) a number of permits – initially for free – with their allocation being equal to their “verified allowance” of emissions.

These allowances are based on a complex calculation that starts with a series of emissions intensity “benchmarks” for the CO2 per unit of output at different categories of site.

Specifically, coal power plants are divided into three benchmark categories: 0.877tCO2/MWh for conventional coal-fired power plants over 300 megawatts (MW) and 0.979tCO2/MWh for conventional coal-fired power plants below 300MW; and 1.146tCO2/MWh for unconventional coal-fired power plants. All gas-fired power plants follow one unified benchmark of 0.392tCO2/MWh.

Unconventional coal sites – those burning coal wastes or a mix of coal and biofuel, including biowaste – are subject to the most generous intensity-based benchmarks. They will receive 30% more allowances than large conventional coal plants and 192% more than gas-fired power plants.

Crucially, allocations are also subject to several “ex-post adjustments” introduced in the MEE allocation plan to “further improve the fairness between generation units of the same category”.

These adjustments give extra allowances in certain circumstances. For example, where a power plant only operates infrequently at a low “load factor”.

Without looking closely at the formula for allocating allowances, it is easy to assume that the emissions intensity benchmarks are the key determinant for buyers or sellers in the carbon market.

For example, French investment bank Natixis simplifies things as follows: if a site’s emissions intensity “exceeds these carbon intensity benchmarks”, it will “have to buy emission permits”.

But, according to Li Lina, the load-factor adjustment means all coal power plants operating below 85% of full capacity will receive extra free allowances.

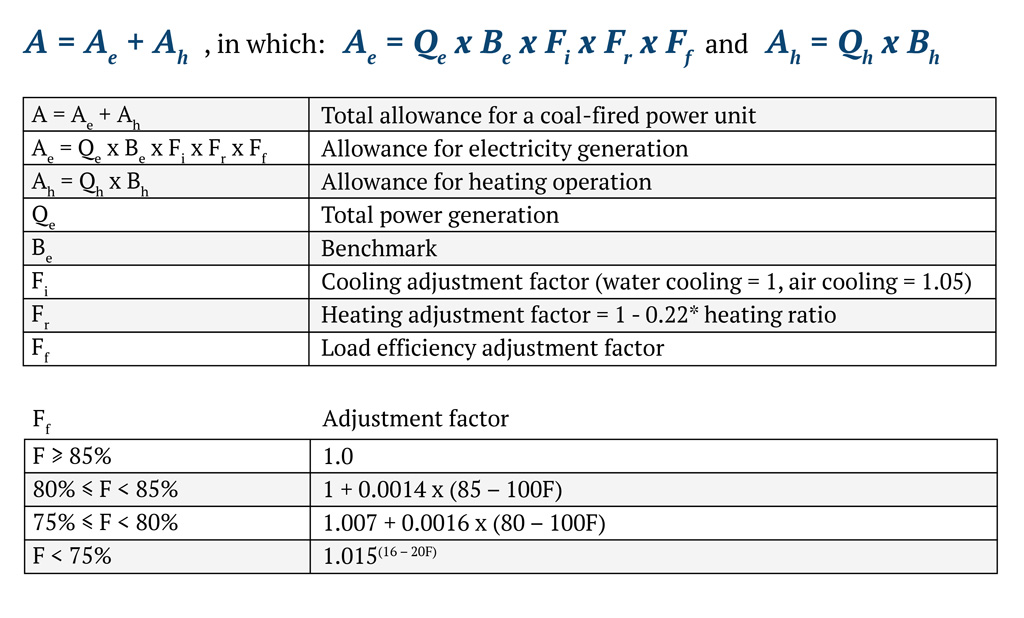

The graphic below shows the full allocation formula for coal-fired power plants, as translated from the official plan by Carbon Brief. It shows that the allocation of permits, denoted “A”, is the sum of allocations for electricity (“Ae”) and heat (“Ah”).

In turn, these allocations are based on the output in terms of the amount of electricity generated (“Qe”) and heat produced (“Qh”), multiplied by the benchmarks (“Be” and “Bh”) and relevant adjustment factors (“Fi”, “Fr” and “Ff”).

(The formula for gas-fired power plants is similar, except without the adjustment factor for cooling and load efficiency.)

The calculation for the load adjustment factor (“Ff”) is set out in the lower table, according to the load factor of the power plant (“F”), which is its output as a fraction of its maximum potential.

Carbon Brief analysis suggests this adjustment could significantly increase the number of free allowances given to plants operating below full capacity at low load factors.

For example, the analysis shows that a coal plant operating at a load factor of 50-70% would receive 3-9.3% more free allowances than a site running above 85% of capacity.

The additional free allowance would be even higher if the output drops below 50%. In China, half of the coal fleet is currently running at a load factor below 50%.

The load-factor adjustment is one of the many ex-post adjustments in the ETS.

The allocation plan also introduces two separate designs for “relieving the compliance burden” of coal-fired power plants and to “encourage the development of gas-fired power generation”.

Specifically, the plan limits the compliance obligation for coal power plants at 20% above their verified emissions, capping the number of allowances they would have to buy.

For example, even if a site’s emissions were 50% above its free allocation, it would only have to buy enough permits to cover its excess up to the 20% compliance obligation.

Reklev tells Carbon Brief that this limit “has nothing to do with emissions reduction”. Instead, it is designed to “favour the dirtiest and least efficient plants” that are already facing financial struggles.

(In the last few years, some 42% to 50% of coal-power plants in China have been suffering from consistent financial losses.)

In parallel, the compliance obligation for gas-fired power plants is capped at their “verified allowance”, meaning overshooting its allowance brings no penalty.

If a plant manages to limit its actual emissions to below its free allowance, it can sell the difference on the ETS market for a profit.

For Reklev, this means there are “no real compliance requirements” for gas-fired power plants. “In a way, the compliance is voluntary for them,” he adds.

Huw Slater tells Carbon Brief that the current allocation framework has been assessed as “potentially leading to oversupply”. (See: Will China’s national ETS cut emissions?)

But, Slater says, it can be adjusted very quickly – “on a regular basis, if need be” – in response to the supply and demand in the market. He adds:

“That’s a positive thing compared to the first phase of the EU ETS, which was not flexible and was difficult to adjust.”

What does the ETS mean for the power sector?

The start of China’s national ETS – initially regulating the power sector alone – comes at a time when the power sector is already undergoing thorough market reforms.

The reforms started in 2002 and continue today, including new priorities on building an effective and competitive electricity market, liberalising tariffs and improving electricity trading.

For now, however, the power sector is still largely governed by administrative mechanisms – such as regulated operating hours and prices – rather than by market forces.

The sector is also a key player in China’s “dual carbon” goals for 2030 and 2060, not only because of the quantity of emissions it creates, but because it can facilitate emissions cuts elsewhere.

The carbon market opens up new possibilities for promoting “deep emissions reductions” in the sector, said Wang Zhixuan, deputy-general-director of the China Electricity Council (CEC), a powerful industry association, in an interview with state-owned Economic Times.

Wang supported the start of the ETS and said it had, in his view, become “unsustainable” to continue promoting power-sector emissions cuts through mandatory standards alone.

But, for Sino-Carbon’s Chen, it is “not realistic” to expect China’s ETS to change things overnight.

He tells Carbon Brief that the ETS will be constrained without deeper power market reform: “It’s like creating a market-based tool in a sector that doesn’t operate according to market forces.”

Professor Yuan Jiahai from the School of Economics and Management of North China Electric Power University agrees that market reforms are crucial to a successful carbon market.

He tells Carbon Brief that if the power sector were exposed to market forces, then the price of carbon from the ETS would increase costs for inefficient coal plants with high emissions, forming a positive incentive to reduce their operation.

The carbon price signal would also help attract more flexible resources to enter the electricity market, such as abundant demand response and energy storage, he says.

But this is not the case today, according to Dr Cyril Cassisa, senior energy analyst at the International Energy Agency (IEA) and lead author of an IEA report on China’s ETS.

He explains that, for now, electricity market dispatch – the process by which individual power plants are switched on or off in response to supply and demand – is largely determined by administrative mechanisms rather than market forces.

A market-based “merit order dispatch”, where the lowest-cost power plants switch on first, would take into account the reflecting carbon price signal created by the ETS would authorise lower-emitting generators to “operate more often”, the IEA report says.

The story for gas-fired power plants is slightly different because of their lack of real compliance obligations under the ETS (see previous section).

According to Li Lina, the ETS rules make gas plants “a pure seller” in the market, meaning they may be able to sell excess allowances but would never need to buy for themselves.

As a result, the national ETS is, in a way, “a subsidy provided to them”, Li says. She adds:

“Some major gas power companies have learned from their participation in the pilot markets that they can receive additional revenues from carbon trading. However, whether other companies will take the position of passive compliance or active participation is up to individual companies.”

The capacity to manage carbon assets varies from one company to another, given that many firms have limited experience of participating in such a market.

This is a point emphasised by Professor Wang Ke from the Center for Energy and Environment Policy Research at the Beijing Institute of Technology (CEEP BIT).

According to Wang, many regulated firms in the pilots did not understand that “the only way to avoid high carbon prices and increased costs” is to “carry out trading evenly throughout the year” and to seize the right time to “sell high and buy low” in a spot market such as China’s ETS.

As a result, firms that are not usually active flood into the market when emission permits are scarce. High demand at the end of the year, just before the compliance deadline, “inevitably” pushes up the price and results in “wide volatility” in carbon prices over the year.

“It is a learning process”, says Reklev. He adds: “Compliant companies are forced to measure and report emissions, and learn about how to receive, trade and surrender emission permits, to prepare them for the future.”

A “mental shift” must take place in the power sector, according to Huw Slater. He adds:

“In order for carbon pricing to play its intended role, the power sector needs to fully comprehend that it is not just as a cost to be absorbed, but is actually incentivising transformation over the medium to long term.”

Will China’s national ETS cut emissions?

President Xi’s “dual carbon” climate pledges give the strongest possible political signal of the need to peak and then rapidly cut the country’s CO2 emissions to zero.

China’s leader has repeatedly referred to the national ETS in the context of meeting his targets. Yet question marks remain over whether the ETS will actually help to cut emissions.

Two studies, both published in April 2021, arrived at opposite answers to this key question.

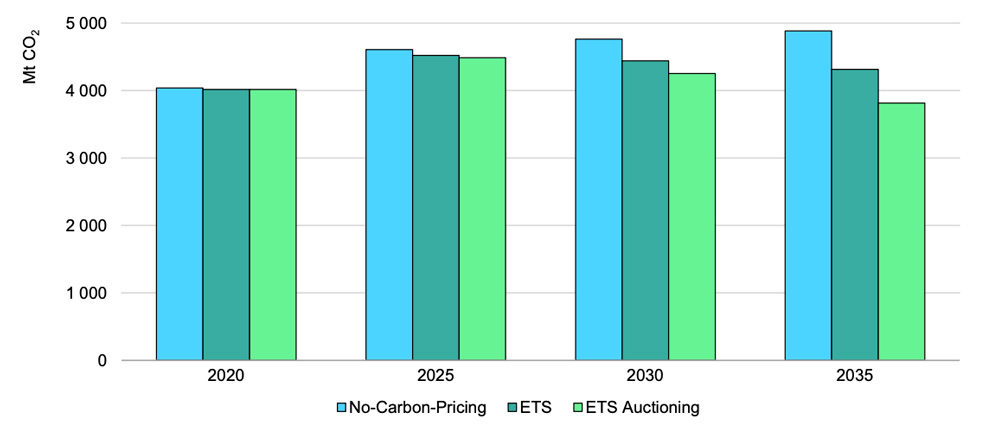

According to a joint report published by the IEA and Tsinghua Institute of Energy, Environment and Economy (Tsinghua 3E), the national ETS “could be an important market-based instrument to help the country meet its recently enhanced climate goals”.

Compared to a no-ETS scenario (light blue bars, below), the report found that the national ETS would be able to “cost-effectively make power sector CO2 emissions peak before 2030” (teal middle bars).

Importantly, however, this conclusion relies on the assumption that the ETS is subject to gradually tighter benchmarks over time – something that has not yet been promised by Chinese regulators.

(According to Dr Yan Qin, lead analyst from consultancy Refinitiv, her modeling forecast a modest “relative reduction” of 200-300MtCO2 per year resulting from the ETS in its current design. Similarly, IEA lead author Dr Cassisa suggests that even the current ETS design would encourage regulated firms to integrate carbon management into the development strategies.)

Tightening benchmarks would mean a gradually rising carbon price on the ETS, the IEA report found, increasing from 100 yuan per tonne of CO2 in 2020 ($15/tCO2) to 360 yuan ($52/tCO2) in 2035.

(Notably, even its starting price assumption of 100 yuan is around twice as high as the average level expected by stakeholders responding to the 2020 China Carbon Survey, at just 49 yuan.)

The IEA report found that the emissions impact of the ETS could be achieved without raising electricity prices, assuming it is coupled with power-sector reforms.

The ETS would be even more effective in terms of cutting emissions if some of the allowances were sold at auction rather than given away for free (green bars, above), according to the report.

In the near term, it found the largest emissions cuts would result from less-efficient “subcritical” coal power plants being used less, in favour of more-efficient “super-” and “ultra-supercritical” sites.

In the medium term, it concluded that the ETS could help to encourage the use of coal with carbon capture and storage (CCS) technology, thanks to the rising price of emitting CO2.

In contrast to the conclusions of the IEA/Tsinghua report, UK thinktank TransitionZero says China’s national ETS, in its current form, “will likely have no impact” on emissions.

TransitionZero estimates that generous benchmark allocations mean the market will start with 1.6GtCO2 or 17% more allowances than regulated sites actually need to cover their emissions in 2019-2020, creating a large oversupply and very low prices. It concludes:

“Since supply is greater than demand and there is no indication that the benchmarks will be tightened, the ‘fair value’ of allowances is zero. Without reform, we expect the price to crash – as it did in the first phase of EU ETS, or remain close to zero.”

(In contrast to the surplus projected by TransitionZero, an “industry insider” cited by Caixin Media says a shortfall of “less than 5%” of emission permits is foreseen in the first implementation cycle. Nevertheless, TransitionZero tells Carbon Brief it is “highly sceptical” that there will be a short supply.)

If the cost of emitting more CO2 under the ETS is zero – or close to zero – it would provide little or no incentive for regulated sites to actually cut their emissions.

According to TransitionZero, it is “widely known that emissions reductions are not the objective” of what it calls the “trial phase” of the national ETS. It calls for reforms to “create scarcity” in the market and, therefore, higher prices. The report explains:

“If the government intends to rely on the ETS to drive [emissions] abatement, we recommend it overhauls the intensity benchmarks and replaces it with a [declining] absolute emissions cap… and a supply adjustment mechanism.”

This pessimistic view of the chances of the national ETS cutting emissions in the near-term is seconded by Lauri Myllyvirta, lead analyst of the Center for Research on Energy and Clean Air.

He argues the current design “completely removes the carbon price signal” due to the allocation plan that is calculated based on the actual power generation outputs. He tells Carbon Brief:

“If the operator decides to generate an additional megawatt-hour of electricity, the allocation is adjusted according to the benchmark. Therefore, there is no incentive to generate less power from coal and no price on carbon.”

Myllyvirta also questions whether the MEE, with its focus on and support for the ETS, is “betting on the winning horse”. He tells Carbon Brief:

“The MEE’s options are to either convince the other ministries and the top leadership to let the carbon market become a strong tool in guiding China’s energy mix, or come up with something else, or let the NDRC and NEA continue to hold the reins on the energy sector, which dramatically limits the MEE’s role in realising the country’s climate targets.”

He adds that the “MEE is wedded to a carbon-trading system as almost their only tool to influence energy sector emissions”. He notes that command-and-control tools, such as administrative measures, targets and quotas, will “remain central” to cutting emissions effectively.

Some other observers of China’s carbon market are supportive of the ETS in principle, but are also conscious of the current design’s shortcomings.

One is Dr Ryna Yiyun Cui, assistant research professor and China programme co-director at the Center for Global Sustainability of the University of Maryland.

She thinks there is “great potential” for the ETS to facilitate coal-plant retirements, but says the “large uncertainties” surrounding the carbon price in the absence of an absolute emission cap in the near future means the near-term impacts are also uncertain.

Alvin Lin, director of climate and energy policy at the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC)’s China Program, also tells Carbon Brief that the ETS will “likely take several years” to have a “significant impact”.

The ETS must be coupled with near-term policies and regulations, such as limiting coal finance and encouraging greater cross-provincial electricity trading of renewable energies, Lin says.

Beyond the power sector, some analysts hope the ETS can also help to smooth the transition for other industries, once they are incorporated into the scheme.

As part of its 2030 emissions pledge, China encourages cities and regions, industrial sectors and enterprises “with the right conditions” to peak emissions before the nationwide deadline.

The steel industry, for example, is the largest source of industrial carbon emissions in China and has proposed to peak its emissions by 2025 before cutting them by 30% over the following five years. Similar deadlines to peak emissions by 2025 are proposed for other industrial sectors, such as non-ferrous metals and building materials.

Li tells Carbon Brief that entering the ETS could ease the path to peak emissions. She says:

“Entering the national ETS will only help to make the industries’ low-carbon transition more smooth, efficient and feasible, while making the ‘peak’ clearer and more transparent through continuous monitoring, reporting and verification of emissions.”

The ETS is “particularly important” for accelerating the transformation of hard-to-abate industries, Li says, because it could provide flexibility in cutting emissions and funds to support innovation:

“Unlike the power sector, for which there are many available and cost-effective mitigation pathways, such as fuel switching to renewable energy, the technology pathways for industries are far too expensive.”

She adds that if some ETS allowances start to be sold at auction, the government could use the revenue to support a research and development fund, similar to the situation in the EU:

“Once the auction is introduced and a climate fund is established, revenues generated from the carbon market could be relocated to finance climate and energy-related projects, such as demonstration pilots for breakthrough technologies.”

In the EU, 78% of the revenue – €57bn in 2012-2020 – was used to finance such projects.

If China “gets the balance right”, says Slater, the carbon market has the potential to be “a really powerful policy instrument” that can respond to reflect increased climate ambition.

“There could be a mismatched expectation about the China ETS,” says the IEA’s Dr Cassisa. He thinks many people are expecting it to be an effective tool to reduce CO2 emissions from the start, only to be disappointed after comparing the current scheme to the government’s wider ambition. He adds:

“There is no perfect scheme – even the EUETS took about 15 years to actually function as expected. What’s important is the vision and the role that the China ETS will play in the country’s low-carbon transition: it is well supported by the government which counts on this market-based policy instrument to contribute to the long-term climate goals.”

Professor Zou Ji, chief executive and president of the NGO Energy Foundation China (EFC), says China’s national ETS can help the country cut emissions more cost-effectively, as well as helping to change the mindset and behaviour of regulated industries.

“The development of the carbon market must speed up,” Zou says, as it will help “turn around the status quo” from regulation-driven obligations towards market-incentivised opportunities.

“I believe without a carbon market, we can probably still achieve [China’s carbon intensity target] through administrative measures…but the cost will be massive. Those measures won’t be cost-effective or provide enough drivers to market participants, nor will they lead to a profound social transition.”

When will the ETS be expanded?

In its first annual implementation cycle during 2021, China’s national ETS will only cover the power sector and captive power plants that exclusively serve industrial sites.

This is in contrast to earlier plans for the scheme, which was due to have regulated emissions across eight sectors that accounted for 50% of China’s total emissions.

The high level of nationalisation and market concentration was a major factor behind starting with the power sector, says Sino-Carbon’s Chen.

In China, the power sector is dominated by a handful of state-owned enterprises (SOEs) known as the “Big Five” and the “Small Noble Four”. By the end of 2019, these firms owned 573GW of thermal power capacity, or 48% of the nationwide total.

This made it easier to avoid conflict over the introduction of the scheme, Chen explains, as well as significantly reducing the scale and challenge of monitoring regulated emissions.

But, now that the national ETS is in operation, more and more experts and policy observers are openly calling for immediate actions to expand its coverage, as proposed in earlier designs.

For example, Prof Duan Maosheng, director of the China Carbon Market Center (CCMC) at Tsinghua University, said in a public forum in March that the power sector is “too lonely”.

“It is the difference in abatement technology and abatement costs from various industries that brings down the cost of carbon emission reduction for the whole society”, said Prof Duan, who participated in the design of the pilots and the national market.

Huw Slater also says that the power sector is “very keen” for other sectors to be involved “as early as possible”. On the other hand, he says, all the other sectors have “similar concerns” as those expressed by power firms, about the possible extra financial burden from carbon pricing.

“But that’s what a well functioning carbon market does: to put a price on carbon and incentivise companies to start looking for ways to reduce emissions across their operations and eventually bring down the abatement cost for the society,” says Slater.

At the moment, there is no official roadmap or timetable for expanding coverage to the eight sectors that were nominated in the initial discussions of the national ETS.

The MEE is reportedly accelerating the sectoral expansion and plans to include at least a few more by 2025. Although policymakers, policy advisors and market participants have brought up different proposals about which of the eight sectors should be prioritised under different timelines, the consensus is that cement and aluminium sector are the strongest candidates.

In a January 2021 interview with state-owned China National Radio, Li Gao, who is the director of the MEE’s department of climate change, outlined a few candidates for the ETS: iron and steel; cement; aluminium; and paper.

Two months later, Jie Liu, general manager of the Shanghai Environment and Energy Exchange, told state-owned China Securities Daily he expected all eight sectors to be covered before 2025.

In April, Prof Zhang Xiliang, director of Tsinghua 3E and head of the national expert group on the overall design of the carbon market, said regulators should “strive to include the cement and aluminium industry within this year”, in an interview with China National Radio.

Speculation over the ETS “marching towards” an expansion was triggered by a notice in May, in which the China Construction Materials Federation, an industry association, claims the MEE has commissioned it for work “related to the inclusion of the building materials industry in the national ETS”. In late June, the China Iron and Steel Association, also an industry association, announced a similar commission on its WeChat account.

Previously, Li Gao has said that expansion would depend on each sector’s “maturity of conditions”.

Chen Zhibin tells Carbon Brief that, from a technical point of view, it is more challenging to develop appropriate benchmarks for the chemical and petroleum sector, compared to others.

They produce a wide range of products using complex manufacturing processes, whereas iron and steel, cement or aluminium have simpler and more homogeneous products and processes.

In 2017, officials attempted to form an intermediate allocation plan covering power, aluminium and cement, before the power sector was eventually selected to kick off the market.

According to state-owned China Economic News, the draft plan had been revised at least three times before being discussed with enterprises and industry associations.

Yet it still triggered major disagreement over “establishing fair benchmarks” and “seeking balanced allowance distribution” across the three sectors, the outlet reported.

“It can be very challenging if the industry associations are not brought on board – as you know, they are very powerful and influential organisations in China,” says Chen.

Will China put a cap on ETS emissions?

Under its current design, China’s national ETS has a flexible cap on emissions that sets it apart from other similar schemes and creates uncertainty over whether it will actually cut carbon.

Historically, China has only ever set itself intensity-based climate targets in terms of its emissions or energy use per unit of GDP, rather than an absolute cap in tonnes of CO2.

For the first time, however, its ‘14th five-year plan’ proposed a dual-cap system “based primarily on carbon intensity control, with an absolute carbon cap as a supplement”.

The absolute cap would apply to China’s emissions overall, rather than being specific to the ETS, but it aligns with long-standing calls for a similar cap in the country’s carbon market.

“Improvements must be made as soon as possible: to introduce an ‘absolute cap’ to ensure the scarcity of the resources and to stabilise the carbon price”, said Prof Duan from Tsinghua, in a public forum held in March 2021.

The purpose of the national ETS has evolved, he said, from reducing carbon emissions under the Copenhagen Accord to serving the new context of peak emissions and carbon neutrality.

A revised draft of the ETS administrative regulation, released at the end of March, added to the description of the cap on emission permits, which it said should also be “based on the requirement of the nationwide cap for greenhouse gas emissions control and periodical targets”.

But, according to Reklev, similar generic expressions have also been written into other policies, so the draft should not be interpreted as a sign that an absolute ETS cap is on the table.

Under the EU ETS, regulated sites receive a fixed allowance within a declining annual cap that ensures emissions will fall. The declining cap is linked to the EU’s rising carbon targets.

According to Prof Zou, it is essential for China’s ETS to build similar linkages between the government’s overall climate ambition and the scale of emission permits in the carbon market.

Failing to do so could result in a market with limited demand and little trading, he says, potentially leaving the ETS “merely as a modality”, rather than an effective tool for cutting emissions.

Li Lina from adelphi says there seems to be a “growing consensus” about moving from an intensity-based to absolute cap, but this is not an “easy task”. She tells Carbon Brief:

“[An absolute cap] will require in-depth technical preparation, such as modelling, political willingness and effective stakeholder engagement. It will also raise the question of which market stability mechanism would be most suitable for China – as the price under an absolute cap may fluctuate more than the intensity cap.”

Dr Qin from Refinitiv says it might not be realistic to expect an absolute cap “before 2025”. The peak emission roadmap and timetable for industrial sectors is “not clear yet” and technical preparation has been “quite slow”, she adds.

A breakthrough, however, might come first via China’s ETS pilots: the new draft of the administrative measures for the Shenzhen ETS proposes to “gradually” put into place an absolute cap that reflects the city’s “economic and social development trends” and “carbon reduction potential”.

The draft specifies that the absolute cap shall be introduced after the city “has realised peak carbon emission”, which, according to the government plan, would arrive in 2022. According to Beijing-based Institute of Public & Environmental Affairs (IPE), the city is likely to have reached the peak in 2010.

What will happen to China’s pilot ETSs?

Although China’s national ETS has now started to operate, the eight existing pilots, formed at the provincial and municipal level, will continue to run in parallel.

These pilots were mostly launched during the 12th five-year plan period (2011-2015) as testbeds for the national scheme and collectively represent the world’s second-largest carbon market.

Eligible sites in the power sector, including captive plants, have already exited the pilots to become part of the national ETS, when it started operating at the beginning of 2021. (There are exemptions for sites that have received pilot permits and started trading for 2019 or 2020.)

China plans to integrate all of the pilots into the national market. However, many technical issues, such as mismatched sectoral coverage and thresholds for inclusion, remain to be solved.

In the meantime, there are question marks over what will happen to the pilots. Following the exit of more than 20 coal-fired power plants for the national ETS, the Shanghai pilot shrinks by a third.

But Chen Zhibin thinks the launch of the national ETS will have a “very small” impact on the pilots, which have broader sectoral coverage and, in some cases, include small-scale emitters.

Because of this, Chen suggests the pilots will remain active and operate in parallel with the national ETS for a long while, during a “transition” period.

Some may even be strengthened, he adds, pointing to the Beijing ETS as an example. Some local governments see them as “a good market tool” for local political priorities, Chen says.

Other pilots may close, if many sites they regulate enter the national ETS when its sectoral coverage evolves. “It all comes down to the enthusiasm of the local governments,” says Chen.

At the moment, there is very little information about how officials plan to address the incompatibility between the pilots and national ETS, except that, on paper, a “gradual integration into the national ETS” is written into the MEE’s interim administrative measures.

Dr Gao Yuning, associate professor of the School of Public Policy & Management at Tsinghua University, tells Carbon Brief that a “clear price” on the national carbon market coupled with “an overwhelmingly high trading volume” would greatly help the integration of the pilots into a single national carbon market.

The most recent draft for consultation of an interim regulation on the national ETS reconfirms the integration and specifies that no new pilots will be approved once the new regulation comes into force.

Notably, the article of the draft covering integration has been newly added, compared to the previous version made public in April 2020.

The official narrative around the pilots has centred around “effectiveness”. An example is Li Gao’s endorsement in October 2020; in a press conference held by the MEE, he said the pilots had “effectively promoted the work” related to climate change and emission mitigation.

This statement is supported by some research carried out by Chinese academics. In a 2018 publication in Economic Review, a national leading journal on social science in China, scholars from the school of economics at Xiamen University concluded that pilots have had “a significant effect” on reducing regional CO2 emissions and, thus, have “realised environmental dividends”.

Dr Gao also led a multinational research team to evaluate the effectiveness of the ETS pilots in carbon mitigation. This research, published in Energy Economics in 2020, confirmed the “contribution” of ETS pilots to emissions mitigation.

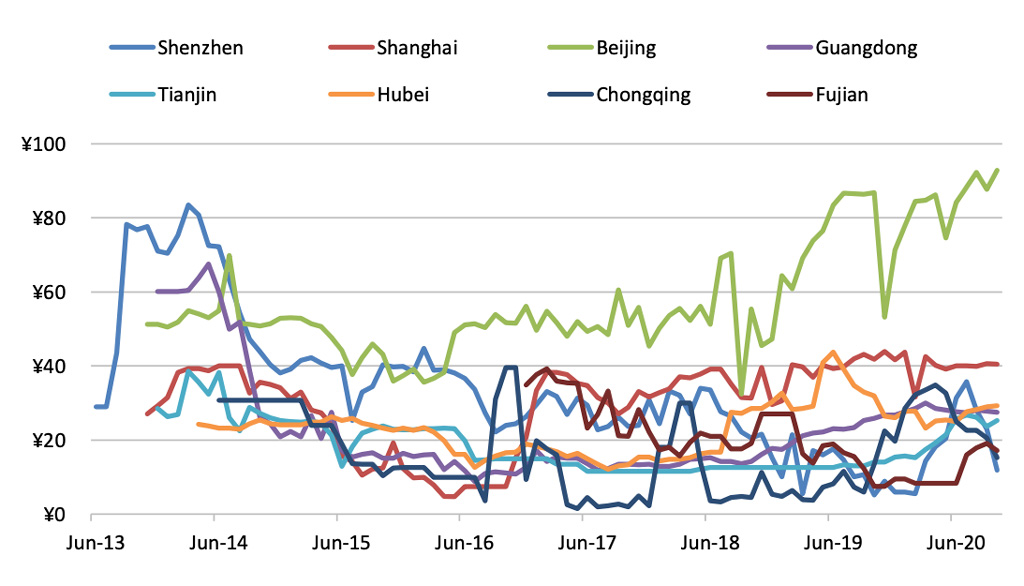

As of March 2021, the eight pilots have covered more than 20 sectors and involved nearly 3,000 regulated sites, trading a cumulative 440MtCO2 of allowances worth 10.47bn yuan ($1.6bn), as shown in the chart below.

| Oct 2014 | Dec 2015 | Jun 2016 | Sep 2017 | Nov 2017 | Aug 2018 | May 2019 | Jun 2019 | Aug 2020 | Oct 2020 | Mar 2021 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cumulative trading volume (MtCO2e) | 13.75 | 67 | 109 | 197 | 200 | 264 | 310 | 330 | 406 | 434 | 440 |

| Cumulative trading value (billion yuan) | 0.52 | 2.3 | 2.99 | 4.5 | 4.6 | 6 | 6.8 | 7.1 | 9.28 | 9.973 | 10.47 |

For comparison, in 2020 alone the EU ETS collected €19.2bn (around 150bn yuan), more than 14 times the total traded value on the Chinese pilots over six years. (The EU ETS was the world’s largest ETS in terms of the emissions covered by the scheme until the start of China’s national scheme.)

According to Dr Gao, the effectiveness of a carbon market is about “whether the carbon price can reflect the total social cost of carbon emissions” and “whether it can help to achieve the carbon mitigation targets”.

At the current volume of trading, he finds it “difficult to discuss” the effectiveness “as a whole”.

One issue he points to is a lack of the trading instruments needed to ensure a deep and liquid market, which would be able to efficiently drive “price discovery” of the true value of carbon reductions.

The eight pilots have seen wide variations in the price of emissions allowances, as shown in the chart below. This is the result of the “different design aspects” of each pilot, such as thresholds for entry, sectoral coverage, eligible entities and allowance allocation, which all have an impact on price, says Slater.

Bin Hui, vice president of Shanghai Environment and Energy Exchange, also said in an interview in March 2021 with People’s Bank of China (PBOC)’s China Finance that “the pilots don’t show very obvious effects on carbon reduction and don’t achieve the expected outcome”.

Chen Yaqin, division chief of green finance at China Industry Bank, expressed a similar view. The lack of participation of institutional investors and financial products in the pilots is, she said, “not conducive to truly reflect the market value of carbon allowances”.

Over the years, many pilots have explored the use of different financial products. They have also experimented with more stringent benchmarks and allowance allocations, such as the “dynamic adjustment” mechanism in Hubei, a sectoral emission control factor in Beijing, and the auction price reserve mechanism in Guangdong, Shanghai and Shenzhen.

But these initiatives are not incorporated in the current design of the national ETS, nor will the institutional investors be allowed to participate in the trading in the initial stage of the market operation.

Li Lina says many valuable experiences in the pilots are “not fully reflected” in the design of the national ETS yet, but this leaves “significant space” for the continuous review and improvement of the national ETS.

What comes next for China’s ETS?

The construction of the national ETS is “sprinting the last mile”, according to Guangzhou Daily, a media outlet supervised by the Guangzhou government.

Since the release of the 14th five-year plan, the PBOC is working with the MEE to launch specific policies and tools on emission reductions before the June 2021 start to trading.

Meanwhile, the MEE is working with the State Council to finalise the interim management regulation for the scheme and to push for its release before the end of the year.

For now, however, there are many concerns among government advisors, such as PBOC’s own research department and financial institutions, over the “inadequate policy framework” and “overall low level of financialisation” of the national ETS.

A paper published by the research bureau of the People’s Bank of China (PBOC) in January 2021 says that the legal attributes of the right to emit carbon under the ETS are “unclear”.

The paper, headed by the bureau chief of PBOC’s research department and co-authored by the deputy chief of its financial research department, also concludes that the market mechanisms around valuing the assets represented by carbon emission rights are “weak”, which “hinders the promotion and innovation of carbon financial products and tools”.

Additionally, Dr Zhou Xiaochuan, former governor of China’s central bank, has said that China must get the design for its carbon market right to prevent it from “following a wrong path”.

The national ETS is built on a few departmental regulations issued by the MEE, namely the interim administration measures on carbon emissions trading, the interim guideline on greenhouse gas monitoring, reporting and verification (MRV) and three interim rules on registration, trading and settlement.

These legal instruments sit at the bottom of the hierarchy of Chinese legislation: they come lower than “administrative regulations” issued by the State Council such as the Electricity regulatory rules and even lower than “laws” passed by the National People’s Congress (NPC) – the state legislative organ – such as the Constitution and the Law on environmental protection.

The current administration of the national ETS is based on a three-tier governance structure led by the MEE and its provincial and municipal-level subsidiaries.

Since the mandate shifted from the NDRC to the MEE in 2018, the MEE has been the only ministry-level government department to have published detailed documents dedicated to the deployment of the ETS.

One long-time observer of the development of the ETS says the department of climate change, which was previously governed by the NDRC, has been stuck in a “deadlock” since NDRC transferred its climate-related responsibilities to the MEE under a government overhaul in 2018. They tell Carbon Brief:

“On one hand, the MEE doesn’t want to share power; on the other hand, its mandate is not adequate to tackle all market-related issues raised from the carbon emissions trading. Consequently, other government organs are not very motivated and enthusiastic about participating in the design process nor the implementation.”

Energy Foundation China’s Prof Zou makes similar points, emphasising the lack of political clout behind MEE regulations and their enforcement. He tells Carbon Brief:

“Low-ranking ministry-level regulations from the MEE have very little weight; they have very limited restriction and influence on the market, let alone dealing with the weakness and uncertainties in implementation.”

He adds that once trading starts under the national ETS, “a massive amount” of market conflict and dispute may occur, which might go beyond the MEE’s mandate and require joint market supervision and law enforcement from other government agencies.

On 30 March, in an attempt to “bolster the authority” of the ETS, the MEE released a revised draft of the interim management regulation on carbon emissions trading rights. This attempts to address some of the long-criticised issues about the legal framework of the national ETS.

For example, it includes multiple government organs in the supervision and guidance of the national carbon market, such as the NDRC, Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (MIIT) and the NEA.

In terms of market supervision, it names the PBOC, State Administration for Market Regulation (SAMR), Securities Regulatory Commission (SRC) and China Banking and Insurance Regulatory Commission (CBIRC).

Compared to the current interim administration measures from the MEE, the new draft also extends the list of potential carbon market offences and significantly raises the level of penalties.

Behaviours such as non-compliance, fraud and market manipulation can now be subject to a fine of 50,000-200,000 yuan ($7,800-$31,000), compared with the current limit of 30,000 yuan.

Additionally, the new draft also proposes to integrate the record of activity in the carbon market to the social credit system, a national governance system built on the principle of “once proven untrustworthy, restrictions should apply everywhere”.

“Untrustworthy” enterprises and individuals with poor social credit scores may receive cross-departmental punishments and sanctions, such as reduced access to credits, government subsidies and business registration.

Some observers, such as the International Carbon Action Partnership (ICAP), argue this new draft marks a “key step” towards State-Council level legislation, which it expects to provide “a more solid legal basis for the national ETS”.

Others, such as Professor Wang Jinnan, member of the National People’s Congress (NPC) commission on environment and resources and president of the Chinese research academy of environmental sciences, call for more fundamental changes to the legal basis of the national ETS.

These changes should “clarify the legal attributes” of the scheme and “confirm the rights to emit” greenhouse gases at the state-legislation level, Wang argues.

Prof Zou tells Carbon Brief that “formal legislation is a must”. This should either be a specific law on carbon emissions trading, or be part of a “law on climate change”, he says.

At the very least, says Zou, it should be embedded in the existing law on environmental protection and relevant amendments should be made while revising the “Civil Code” and relevant economic laws.

The key of these legislative moves, according to Zou, is to position the ETS as a “market of asset and property rights”, which would help resolve its technical challenges. He tells Carbon Brief:

“Our carbon market is mainly designed by engineers. As a result, the indispensability of carbon emission permits as a factor of production was not well understood. Elsewhere, the real-estate sector, for example, can’t develop without access to land rights.”

Back in 2011, the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences had already formulated an expert draft for consultation of a “climate change response act” under the commission of the NDRC and the then-Ministry of Environmental Protection (now ‘MEE’), following the NPC Standing Committee’s 2009 decision on “incorporating climate legislation in the legislative agenda”.

However, it was not until very recently that climate legislation was brought back under the MEE’s remit.

In a 27 April press conference held by the State Council’s information office, Li Gao from the MEE said the ministry is working with the NPC and other departments to push forward the formulation of a “comprehensive and specific” climate law.

However, this climate legislation was not mentioned in the NPC’s annual legislation plan for 2021, which had been revealed a week earlier.

Pushback against the idea of strengthening the legislative basis of the ETS is more likely to come from China’s legislators rather than other ministries, Huw Slater tells Carbon Brief.

The ministries have formed “a broader consensus” on the scheme after years of engagement with it, he says, whereas the State Council and the NPC are “not very familiar”. Slater adds:

“But now it is a high-level government priority with significant momentum. This may help overcome any institutional resistance and create momentum so that some of those actors recognise the importance of carbon pricing.”

Despite uncertainty over a robust legislative basis for China’s national ETS, expectations are still running high over the potential for a market that could be worth billions of yuan.

According to the 2020 China Carbon Survey, the average price expectation from stakeholders of the national carbon markets starts at 49 yuan ($7.6) per tonne, with a prospective “steady rise” forward, up to 167 yuan ($26) in 2050.

The launch of the national ETS is triggering a “carnival for capital”, with many waiting to take a share of the “cake”, according to various Chinese media outlets, such as Yicai and China Securities Times.

Xinhua’s Economic Information Daily reports that the cumulative value of allowances traded on the scheme could exceed 100bn yuan ($15.6bn) by 2030.

China’s Guorong Securities tells state-owned China Securities Daily that the market value could reach 150bn yuan ($23.3bn) – and 600bn yuan ($93.3bn) including trade in derivatives.

The prospect of a billion-yuan market is fuelling suggestions on how to invest the proceeds, if some allowances start to be sold at auction under the national ETS.

The new draft for consultation of the interim administrative regulation proposes to establish an “ETS fund”’ to support market development and projects for reducing greenhouse emissions.

Under the EU ETS, a portion of auction revenues are used for climate adaptation and mitigation, such as helping poorer regions shift away from carbon-intensive industries, with a further share going towards innovation.

Dr Gao, whose study showed “carbon leakage” from China’s pilot regions to other areas, invites policymakers to consider the social economics that may come along with carbon pricing, which, according to him, are now “often isolated” in the ETS related discussions. He adds:

“The less developed regions should receive more transfer payments from funds while still playing a fair game on the carbon market themselves. This way, we can achieve a better balance between an effective and efficient carbon market and the fairness of the social and economic development of the less developed regions.”

Li Lina says the current market design has not yet taken into consideration carbon leakage for the reason that the power sector is not “trade-exposed” in the same way as industry.

If the national ETS starts covering trade-exposed sectors and the carbon price reaches levels seen in the EU ETS, she adds, then firms might have an incentive to transfer their activities abroad.

In the short- to medium-term, however, the theoretical problem of carbon leakage from China to other countries where an ETS or carbon tax is absent is not the biggest concern.

Instead, she says a lot of attention is currently focused on the potential impacts on China’s export-oriented industrial sectors from the EU’s proposed “carbon border adjustment mechanism” (CBAM), which would tax certain imports of carbon-intensive goods.

This article was updated on 16 July 2021 to confirm that trading had started.

Note on methodology

Carbon Brief used the "Unified Social Credit Identifier” (USCI) embedded in the “List of key emission entities” published by the MEE in December 2020 to cross-reference public information on each “key emission entity” covered by the China national ETS in the first implementation cycle.

This included business license, shareholder and company structure accessed through www.qcc.com, a private Chinese website certified by the Chinese authorities for business credit reporting, as well as information from each company’s official website. The information gathering and data analysis was carried out in March 2021.

“Captive power plants” are labelled only if a firm’s dominant business activities are industrial or commercial, rather than “power generation” or “heat and power”, and if no public information indicates that the firm supplies heat and/or power to the public network.

In a few rare cases, heat and/or power generation is the only activity of a firm that is solely owned by an industrial park or an industrial producer. These cases were verified manually and are only considered as “captive” if they are built as a supporting infrastructure to the industrial activities.

“Fuel” type was identified based on the information disclosed in a firm’s business scope and its official website. Firms that mention “waste incineration”, “biomass”, “new energy”, “distributed energy” or “energy investment” were verified manually.

The fuel type was labelled as “gas” only if a firm clearly states it is fuelled by gas, or uses gas-fired heating and power generation technologies, and/or contains “gas” in the company’s name.

-

In-depth Q&A: Will China’s emissions trading scheme help tackle climate change?