In-depth Q&A: What food waste means for climate change

Orla Dwyer

10.03.23Orla Dwyer

03.10.2023 | 3:27pmWasted food – if it were a country – would be the third largest source of greenhouse gas emissions in the world, according to the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization.

Reducing food waste can help to cut down on these emissions, feed those who are hungry and improve food security.

Food waste experts tell Carbon Brief that “food loss and waste” remains a “major issue”.

There are a range of solutions to tackle the problem, they say, but more action is needed to put such actions in place.

This in-depth Q&A outlines why wasted food causes emissions, why it has become such a big issue and how countries and companies plan to slash waste in the years ahead.

- What is food loss and waste?

- Where does food go after it is wasted?

- Why is food waste a climate issue?

- What are countries doing to reduce food waste?

What is food loss and waste?

Around one-third of all food goes to waste during different steps of the production process – from farm, to truck, to fridge.

Food “loss”, according to the UN Environment Programme’s (UNEP) 2021 food waste index report, is defined as all of the edible parts of food that end up discarded in early parts of the supply chain – for example, vegetables that rot in fields before being picked, crops hit by disease and meat that spoils due to lack of transport refrigeration.

These losses occur before the food reaches supermarkets. Around 15% of food produced globally is lost during harvest or slaughter, a 2021 WWF-UK report found.

Food “waste” refers to the discarding of food and the inedible parts of food that are not consumed by people at a retail, food service or household level. This waste can end up in landfill, compost or animal feed.

The vast majority of food waste goes to landfill. As this food breaks down over time, it generates greenhouse gases, primarily methane. (See: Why is food waste a climate issue?)

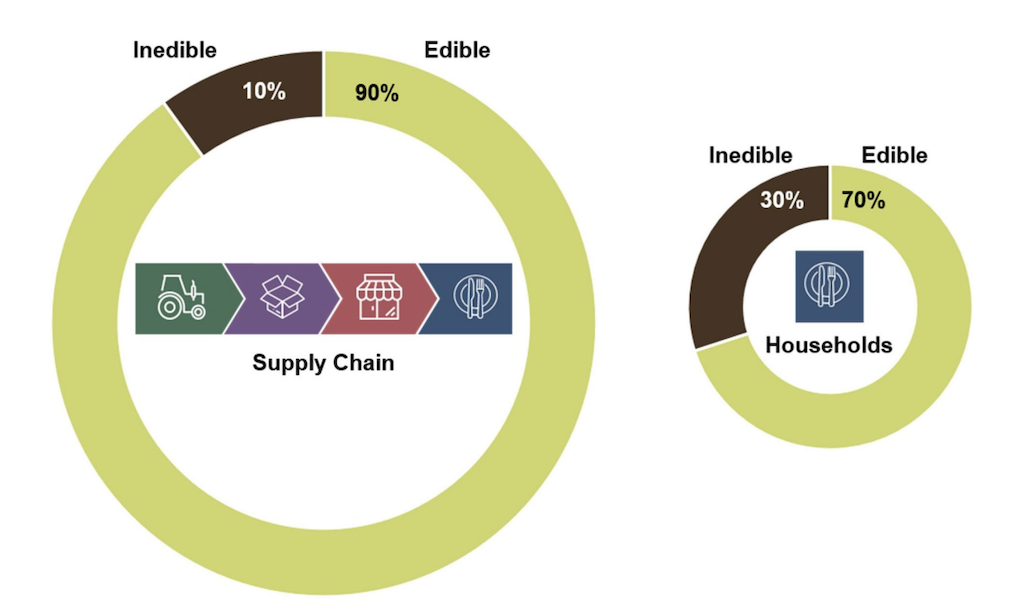

The chart below shows that the majority of supply chain and household food loss and waste is considered sufficiently edible.

A 2020 World Bank report said that reducing food loss and waste can “make a profound difference” for multiple challenges – reducing hunger, strengthening economies and protecting the environment.

In addition to avoiding greenhouse gas emissions, shifts and reductions in food loss and waste can “promote environmental co-benefits” for biodiversity along with soil and water health, a recent study noted.

Dr Christian Reynolds, a food loss and waste expert and a reader in food policy at the Centre for Food Policy in City, University of London, says waste is a constant struggle because “everybody’s got to eat and food degrades”. He tells Carbon Brief:

“Food loss and waste is a major issue for us as a civilisation to tackle. But it’s something that we’ve been trying to tackle for a long time.”

The UNEP report estimates that food waste from households, retail and the food service industry amounts to 931m tonnes every year. Of this, 61% comes from households, 26% from food service and 13% from retail.

Where does food go after it is wasted?

The majority of food loss and waste ends up in landfills, where it produces methane. Food is the most common material put into landfill and incineration in the US, according to the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).

Incinerating waste results in a lower greenhouse gas impact than allowing it to decompose in a landfill.

Composting food waste also has a smaller environmental impact, resulting in 38-84% fewer emissions compared to landfill, a 2023 Nature study found.

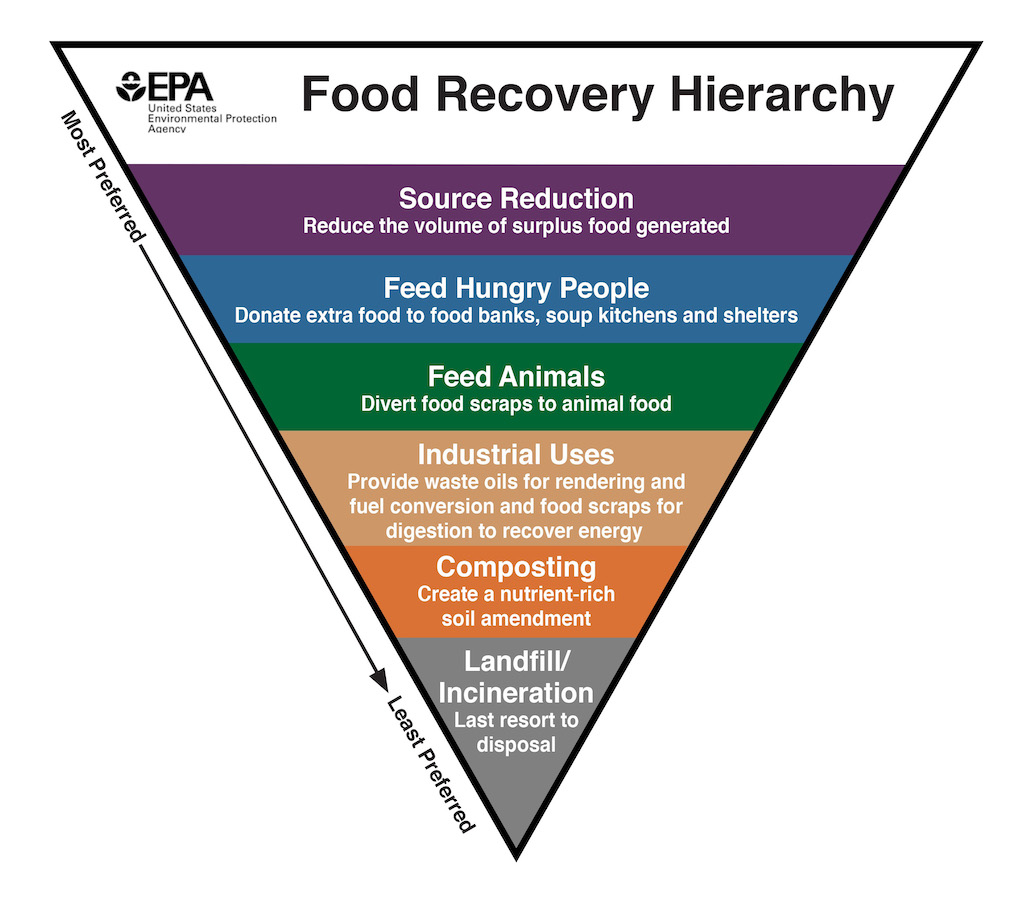

The image below shows the EPA’s “food recovery hierarchy”, an inverted pyramid highlighting the most to least preferred options when dealing with excess food.

The most favourable option is to reduce the amount of extra food produced in the first place. The “last resort” choice is to dispose through landfill or incineration. Composting is the second “least preferred” option.

Dr Dawn King, a senior lecturer in environment and society at Brown University in Rhode Island, says that the main priority for food waste should be, as outlined by the EPA, to “get food to people who are hungry”.

Composting often requires either an organised pickup or a garden to compost at home, she tells Carbon Brief, so it is not always an available option for households.

Individuals can take action on food waste in other ways, but options can be limited, Reynolds says. He tells Carbon Brief:

“For both dietary change and for food loss and waste, there is an individualisation of responsibility to some degree. But, also at the same point, there are some system drivers for this.

“An individual can decide what portion and pack size of something they purchase. However, they can’t decide what portion and pack sizes are on display in the supermarket.”

Why is food waste a climate issue?

Producing food in general – particularly meat and dairy – requires a significant amount of land, water and other resources. It is also often costly to produce.

The global food system from production through to consumption is responsible for around one-third of the world’s annual human-caused emissions.

Greenhouse gases from wasted food account for around half of these emissions, a 2023 study found.

The study said that, in 2017, global food waste resulted in 9.3bn tonnes of CO2-equivalent (GtCO2e) emissions – roughly the same as the total combined emissions of the US and the EU that same year.

As food breaks down in landfill, it generates methane – a potent greenhouse gas. Per unit of mass, methane is 84-86 times stronger than CO2 over 20 years and 28-34 times as powerful over 100 years.

The table below shows a WWF-UK analysis of how different commodities, such as fruit, vegetables and meat, contribute to the global level of food waste.

| Commodity | Volume of waste (million tonnes)³ | % of total production | Value of waste ($million)⁴ |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fruit & vegetables | 449 | 26% | 160,157 |

| Roots, tubers & oil crops | 261 | 15% | 44,095 |

| Meat & animal products | 153 | 12% | 99,738 |

| Cereals & pulses | 196 | 14% | 56,199 |

| Fish & Seafood | 25 | 44% | - |

| Other | 90 | 6% | 8,930 |

It is not only the methane emissions from rotted food that cause an environmental issue. All of the emissions associated with the production of a piece of food that is wasted – from the land used to grow it to the plastic used to package it – could have been avoided if the food was not produced and left to waste.

Food wasted in later stages of the supply chain – such as after it reaches a supermarket shelf or a consumer’s fridge – leads to even more waste due to the extra resources needed for packaging and transportation. (Food transport is not widely considered to majorly contribute to total food emissions, but some research challenges this assumption.)

The EPA says that 560,000 square kilometres of agricultural land is used to produce US food that is lost or wasted each year – an area the size of California and New York combined. This food would provide enough calories to feed more than 150 million people each year, the EPA adds.

Another issue to consider is the “carbon opportunity cost” of the land used to grow food, especially high-emitting options, such as meat and dairy.

In short, if agricultural land used to grow wasted food was instead restored to forest or wild grasslands, the land would be able to store more carbon, with additional benefits for biodiversity.

So tackling and reducing food loss and waste would reduce emissions from across the supply chain and prevent needless resources being used to produce food that does not end up being eaten.

According to the UN, food loss and waste generates around 8% of all human-caused greenhouse gas emissions each year – around the same as the global tourism industry. This also comes at a time when as many as 783 million people were impacted by hunger in 2022, according to the FAO.

From a climate perspective, the right solutions to waste can help “unlock a fairer, [more] equitable and resilient food system”, says Reynolds.

Reynolds says food waste should be a bigger focus point for governments in their efforts to reduce emissions. He tells Carbon Brief:

“That’s an obvious thing that we could be putting within the NDCs [Nationally Determined Contributions, pledges made by each country under the Paris Agreement] as a piece of policy work to actually highlight food loss and waste reduction as part of the NDCs, and then that would cascade downward.

“There has been some discussion of food loss and waste within the wider climate, but it seems a very obvious pathway that we are not using to our fullest extent.”

What are countries doing to reduce food waste?

Food waste is targeted in a number of different ways through policy, campaigns and individual action.

A global goal to reduce waste forms a key part of the UN’s 12th Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) – a set of targets for countries to help tackle climate change, end poverty, improve health and boost economic growth.

One section of SDG 12 aims to halve per-capita global food waste at the retail and consumer levels, and also reduce food losses in production and supply chains by 2030.

But many countries have yet to tackle the issue head on in their policy plans relating to climate.

According to a report by the climate-action non-governmental organisation WRAP, 21 countries committed to reducing food loss and/or food waste in their NDCs submitted before the COP27 climate summit last year.

Of the 193 countries that submitted NDCs, nine countries specifically committed to reducing food waste and 14 committed to reducing food losses, the report found.

Several other countries including the UK, South Africa and parts of the EU refer to other policy documents that mention food loss and waste reduction, but the report notes these policies are not directly included in the NDCs.

The UK and EU

The UK government relies on voluntary action to reduce food waste. For example, in recent years a number of UK supermarkets have removed “best before” dates from certain products in an effort to reduce waste.

A “best before” date is used to signify when food is at its peak quality. A “use by” date is a stricter rule noting the timeframe by which food is safe to consume.

Removing “best before” dates from fresh products such as apples, bananas and potatoes could help to “prevent 100,000 tonnes of household food waste”, according to a 2022 WRAP report.

However, in terms of official policies, the UK government recently disposed of plans to make food waste reporting mandatory for some businesses. Campaigners criticised the decision and said these measures could have reduced food prices and helped tackle climate change, the Guardian reported.

Reynolds says this decision was a “real shame and a missed opportunity” for the UK government. He tells Carbon Brief:

“Food loss and waste is being measured by many companies already. The majority of the supermarkets already are doing this, it’s just not publicly disclosed. So I think there is already some of this happening, it’s just that a piece of legislation would have levelled the playing field.”

Dr Carrie Bradshaw, a food waste policy expert and lecturer in law at the University of Leeds, adds that mandatory reporting is a “necessary, but not sufficient, measure to tackle food waste”.

Measures are also taking place in certain EU countries and on a wider scale across the bloc.

The European Commission has proposed setting targets for EU countries to reduce food waste by 10% in processing and manufacturing, and by 30% at retail and household level by 2030.

In France, supermarkets are legally required to donate unsold food instead of letting it go to waste. A similar law exists in Italy.

Bradshaw says there are many “economic, social and environmental implications of food waste”. She tells Carbon Brief:

“Arguably in seeking to tackle food waste, we should be aiming not at absolute reductions…but reducing the broader climate and other environmental impacts of food waste.

“Distributing the costs of food waste reduction fairly across the supply chain remains a real challenge for food waste reduction, and is why measures which take a joined-up, whole supply chain approach are likely to be important. This in turn is a limitation of the more targeted efforts you see in France, China or South Korea.”

The US

Food waste remains a growing problem. In the US, food waste grew by almost 5% between 2016 and 2021.

Research suggests that as much as half of all US food produced is left to rot, fed to livestock or put from field to landfill due to “cosmetic standards”, the Guardian reported.

The US department of agriculture advises a number of ways for farmers to reduce food loss and waste – including partnering with food delivery box services or donating food.

At the end of last year, Congress approved the Food Donation Improvement Act which “expands liability protections for the donation of food and grocery products”. A group of US lawmakers also recently proposed federal legislation aimed to halve food waste by 2030.

On a state level, some states offer tax breaks to farmers and businesses who donate food rather than letting it go to waste. Others are diverting food waste away from landfill.

Certain restaurants, cafés, supermarkets and stadiums in New York City are required to separate food scraps and other organic waste.

Since a composting law took effect in California at the start of 2022, every jurisdiction in the state has been required to provide organic waste collection services for households and businesses.

But there has been “uneven progress” on the goal to redirect food waste away from landfill since the “groundbreaking” law was implemented, the Los Angeles Times reports.

King says that a lot of food waste is “preventable”, but she believes there is a lack of incentive for many farmers to avoid it. In some cases, it is not “economically efficient” for farmers to sell slightly imperfect fruits and vegetables, King adds.

China

A Nature study published in 2021 estimated that about 27% – or 349m tonnes – of food went to waste each year from 2014-18 in China.

In 2020, the Chinese government announced the “clean plate campaign” as a measure to tackle food waste and raise public awareness on food security.

Sally Qiu, a research associate at the Center on Global Energy Policy at Columbia University, says this campaign, and an anti-food waste law implemented in 2021, form part of China’s wider focus on food waste.

The anti-food waste law is a “code of conduct for different entities – like government, companies, schools, catering services – to improve their food procurement management process”, Qiu tells Carbon Brief.

She notes that the “clean plate campaign” appears to be “coming from a food security standpoint, rather than a climate crisis standpoint”. She adds:

“One of the side effects is that reducing food waste is good for the climate.”

Qiu says there has not been a substantial evaluation of progress so far on the success of these initiatives. She says:

“It is a very well-intended campaign. They don’t want people to waste things. But, just based on what I have seen so far, it’s more of an ideal rather than a very substantial achievement [in] reducing a lot of food waste.”

China’s action plan to hit peak emissions by 2030 sets out a goal to “put a resolute stop to wasteful behaviours, and work tirelessly to reduce food waste in the catering industry”. Qiu describes this goal as a “turning point” of the Chinese government making the “connection with food waste and climate change”.

Qiu says the campaign and law are a “good start”, but more tangible targets may have a bigger impact. She tells Carbon Brief:

“These laws and initiatives are more like they’re encouraging people to do certain things. But it didn’t really say what the goal [is]. Peaking carbon has a very clear goal of 2030…I think maybe for food waste, they can come back with more empirical research…Maybe they can set a more quantitative target, an evidence-based target.”