In-depth Q&A: What does the global shift in diets mean for climate change?

Josh Gabbatiss

09.15.20Josh Gabbatiss

15.09.2020 | 7:00amTo limit global warming while feeding an expanding population, every part of the food system from farming to refrigeration will likely need to become cleaner and more efficient.

At the same time, there is growing recognition of the important role people’s diets will need to play in achieving international climate targets.

The food people eat is heavily influenced by culture, geography and wealth, but governments can also play a key role in influencing dietary change, through everything from farming subsidies to healthy eating guidelines.

In this Q&A, Carbon Brief examines how diets are already changing and what will be required to ensure the world’s food consumption is “climate-friendly”.

- What is a ‘climate-friendly’ diet?

- Why do people’s diets need to change?

- Are people in high-income nations eating more climate-friendly diets?

- How are diets changing around the world?

- When will the world reach ‘peak meat’?

- Can dietary guidelines help achieve climate targets?

- What else can governments do to alter diets?

What is a ‘climate-friendly’ diet?

There has been extensive discussion of what constitutes a “climate-friendly” diet. While there is no universally accepted answer and no internationally agreed guidelines, the scientific consensus has converged on a handful of key features.

Chief among these is the importance of keeping animal products – particularly red meat, such as beef, and dairy – to a minimum.

Nevertheless, the impact of meat and dairy on the climate is a complex and contentious issue, which is explored in far greater depth in Carbon Brief’s interactive explainer.

- Interactive: What is the climate impact of eating meat and dairy?

- Experts: How do diets need to change to meet climate targets

- Guest post: Coronavirus food waste comes with huge carbon footprint

- Guest post: Are low- and middle-income countries bound to eat more meat?

- Webinar: Do we need to stop eating meat and dairy to tackle climate change?

Other elements of climate-friendly diets are a diverse array of minimally processed grains, tubers, fruits and vegetables, preferably varieties that are less likely to spoil and do not rely on energy-intensive transport, such as planes. (Although food transport is a relatively small consideration for overall emissions.)

This article will focus primarily on the consumption of red meat and dairy products, as these have been the main focus of efforts to curb dietary emissions.

It will also mainly address greenhouse gas emissions from food, while recognising that there are several – often, but not always aligned – issues at play when optimising diets, including health, adequate nutrition and other environmental impacts.

Why do people’s diets need to change?

Concerns about the impact of meat and dairy consumption on the climate and the wider environment are not new.

However, over the past decade there has been a growing focus on sustainable diets that can feed the millions of people around the world who are malnourished or obese, while remaining within planetary limits.

A paper published in 2007 stated that the emissions from meat “warrant the same scrutiny as do those from driving and flying”. Two years later, the influential British economist Lord Stern suggested eating meat would, ultimately, become as unacceptable as drink driving.

Nevertheless, so far diets have not been subject to the kind of political attention that has driven action to decarbonise other high-emitting sectors.

Prof Tim Benton, who leads the energy, environment and resources programme at Chatham House, tells Carbon Brief the climate-food link has been “given legs” by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) setting out the climate benefits of dietary shifts.

The launch of the IPCC’s special report on climate change and land in 2019 made it clear the goals of the Paris Agreement require a focus on food systems, with much of the resulting news coverage focusing on the scientists’ references to dietary change.

Dr Hans-Otto Pörtner, a co-chair of one of the IPCC’s working groups, said at the time they “don’t want to tell people what to eat…But it would indeed be beneficial, for both climate and human health, if people in many rich countries consumed less meat, and if politics would create appropriate incentives to that effect.”

There is already much discussion around efforts to create a “Paris-compliant” food system by reducing emissions per unit of food produced, as well as using “climate-smart agriculture” and “sustainable intensification” to feed a growing population.

However, as a recent letter by a group of medical professionals to the Lancet points out, dietary change has been relatively “neglected” in international climate politics.

An analysis in 2018 of existing nationally determined contributions (NDCs) found that, while 96 addressed agriculture and 88 mentioned food waste, none mentioned diets.

A recent report produced by a group of organisations including the UN Environment Programme (UNEP) confirmed that no national climate plans explicitly discuss sustainable diets.

It concluded that adding diets and food waste to NDCs could set a course for cutting emissions by an extra 12.5bn tonnes of CO2 equivalent (GtCO2e) each year, 20% of the reductions needed to deliver on the Paris Agreement’s 1.5C target by 2050.

Meanwhile, without wealthier countries curtailing their consumption of red meat and dairy products, in particular, it is likely they will exceed regional targets and make the Paris Agreement targets of 1.5C or “well below” 2C warming harder to reach.

One study found that at current rates of emissions growth from the sector, livestock could take up 37% and 49% of the global emissions budget “allowable under the 2C and 1.5C target, respectively,” in 2030.

Failure to implement “animal to plant protein shifts” would make drastic changes from other sectors “far beyond what are planned or realistic” necessary, wrote Dr Helen Harwatt, an environmental social scientist at Harvard Law School.

Dr Jonathan Doelman, a scientist working on integrated assessment models at the Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency, tells Carbon Brief that dietary change features “more and more” in pathways to Paris targets. “It’s getting harder and harder to get to 2C or 1.5C with normal measures,” he says.

One reason for this is that dietary change not only reduces emissions directly, but also means more land is made available as livestock pasture is freed up.

In many future scenarios, this sparing of land makes space for the mass rollout of bioenergy with carbon capture and storage (BECCS) and afforestation projects. Dietary changes could mean there is less risk to food security as these projects compete with agriculture.

Doelman describes such changes as a “win-win” as there is also less risk that emissions from food production will be outsourced to other countries:

“You are basically 100% sure it will help, whereas, indeed, if you just put more forests in the UK and don’t care about what happens to the food production you displace, you don’t know if it’s actually a net gain for the climate.”

Dr Paul Behrens, a researcher who focuses on the environmental impact of human consumption at Leiden University, tells Carbon Brief that dietary change also has many extra benefits:

“It may be possible to hit the Paris Agreement with some heroic assumptions on how you could use sequestration without dietary change, but you’re not going to address water scarcity, soil degradation, biodiversity loss and eutrophication.”

The release of the EAT-Lancet planetary health diet in 2019 – described as the “first attempt to set universal scientific targets for the food system” – marked a “watershed” moment, with a call for a reduction of more than 50% in global meat consumption.

The study, produced by 37 scientists, provoked concerns from the food and agriculture industry, and a statement from the Italian government said its recommendations could “end up being nutritionally deficient and even dangerous”.

But the report’s authors are clear that in their view reaching the Paris Agreement targets is “not possible” by just decarbonising the global energy system, stating:

“Transitioning to food systems that can provide negative emissions (i.e. function as a major carbon sink instead of a major carbon source) and protecting carbon sinks in natural ecosystems are both required to reach this goal.”

Are people in high-income nations eating more climate-friendly diets?

Globally, there is no doubt the consumption of high-emissions food products has increased substantially in recent decades.

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) data shows that production of milk has more than doubled and meat more than quadrupled over the past 60 years. Production of beef, the food with the largest emissions footprint, has doubled.

What is more, analysis conducted by Chatham House shortly before the Paris Agreement in 2015 found that in Brazil, China, the UK and the US, public understanding of the link between diet and climate change was “very low”.

Despite this, there are suggestions that high-income nations, particularly in Europe, have started shifting towards more plant-based diets.

Quinoa salad bowl in healthy vegan restaurant. Vienna, Austria. Credit: Glenstar / Alamy Stock Photo.

This apparent trend has seen the French president backing a citizens’ call for a 20% reduction in meat and dairy consumption, as well as Germany described in a report by the US Department of Agriculture as leading a “vegalution” – vegan revolution – in Europe.

The growth in vegetarian eateries and plant-based alternatives appears to be matched by the public’s eagerness, with 63% of Germans, 51% of Canadians and 50% of British people trying or willing to reduce their meat consumption, according to various surveys.

Moreover, while health and animal welfare are frequently cited as factors behind these choices, polling has also shown consumers highlighting the environment as an important factor in their decisions.

However, Laura Wellesley from Chatham House says that while the landscape has changed since she started working on this topic before COP21 in Paris, the extent to which behavioural changes are actually taking place is “still unclear”.

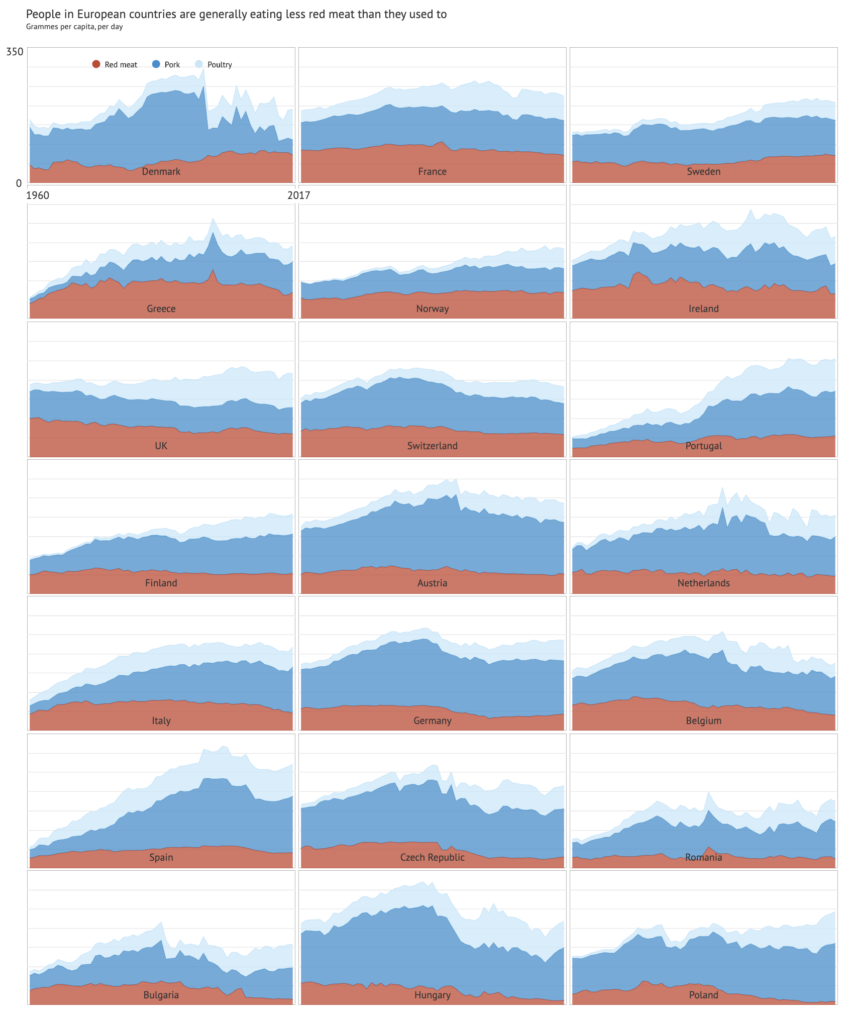

The chart below shows how per-capita meat consumption is changing across Europe, based on food balance sheet data from the FAO. Contrary to the idea of a shift to plant-based foods, overall meat consumption has seen a general increase, although most nations have experienced declines in red meat intake.

Overall per-capita meat consumption is roughly twice the global average in Europe and dairy consumption is around three times higher, according to FAO data. Meat consumption in Australia and the US is even higher.

According to Benton, a key driver behind the decline in consumption of beef and lamb in some “western” countries is “red meat is bad” public health messaging that stretches back to the 1970s.

Meanwhile, high levels of meat consumption in nations such as Spain and Austria have been attributed in part to subsidised animal farming that results in cheap, easily available products.

Eastern European countries, including Romania and Bulgaria, see lower overall meat consumption, which can be linked to lower average incomes.

Dr Marco Springmann, a population health scientist at the Oxford Martin Programme on the Future of Food tells Carbon Brief that, while some wealthier nations have shown a drop in per-capita red meat and dairy consumption, it is generally coming from a very high level.

The notion of a recent shift to vegetarianism and veganism is largely based on a combination of national diet data, consumer surveys and industry and retailer reports on plant-based foods.

However, Springmann says national dietary surveys have “huge problems”. Specifically, they are often based on self-reporting and there is evidence people in high-income nations under-report consumption, particularly for products they feel they should not be eating.

The UK government’s “family food” survey even includes the disclaimer: “It is a widely recognised characteristic of self-reported diary surveys…that survey respondents tend to under-report”.

“If people really ate only what is reported in the national dietary survey of the UK, everybody would be underweight by quite a bit,” says Springmann.

Meanwhile, the global “alternative meat” market was worth $14bn last year, according to research by Barclays, with particular interest among young people for dairy- and meat-free options.

This is just 1% of the global meat industry, although the same research predicted this could rise to 10% by 2029.

However, there is scepticism among experts. Wellesley tells Carbon Brief that in the UK the optimism of the “Greggs vegan sausage roll moment” should be treated with “a degree of caution”:

“We have had behind-the-scenes conversations with major retailers who have said that although meat alternatives sales have increased, so too have sales of conventional meat options.”

As the charts above indicate, declines in red meat tend to be made up for by an increase in pork and particularly poultry consumption.

While emissions from these products are far lower per gramme than red meat, there are concerns about some of the knock-on effects of their increased consumption, particularly due to their reliance on soy as an animal feed.

Soy production is a major contributor to deforestation in South America. Pig and poultry farming in the UK consume 29% and 53%, respectively, of the solid “cake” derived from soy which is used to feed animals and, to a much lesser extent, humans.

Separately, a report by the European Environment Agency found that, while the EU had seen a 14% overall decline in per-capita beef consumption from 2000-2013, the environmental benefits were “somewhat offset” by a 15% increase in consumption of cheese, another product that comes with a considerable emissions footprint.

While red meat is still widely recognised as having the largest climate impact, some scientists and NGOs have emphasised the need to address all animal products when targeting more climate-friendly diets.

“My personal viewpoint…is that what you really need to be doing is cutting your consumption across the board, of all kinds of animal products,” Dr Tara Garnett, leader of the Food Climate Research Network tells Carbon Brief.

How are diets changing around the world?

Garnett tells Carbon Brief that, in her view, globally, there is increasing awareness of the impact that land-use change, deforestation and livestock methane is having on the climate.

However, she notes that outside of “northern” nations, an appreciation of the role people’s individual diets play in driving climate change is “less clear” to her.

Dr James Bentham of the University of Kent, who recently published a study based on FAO data examining worldwide dietary trends, tells Carbon Brief there has been a “global convergence” in diets.

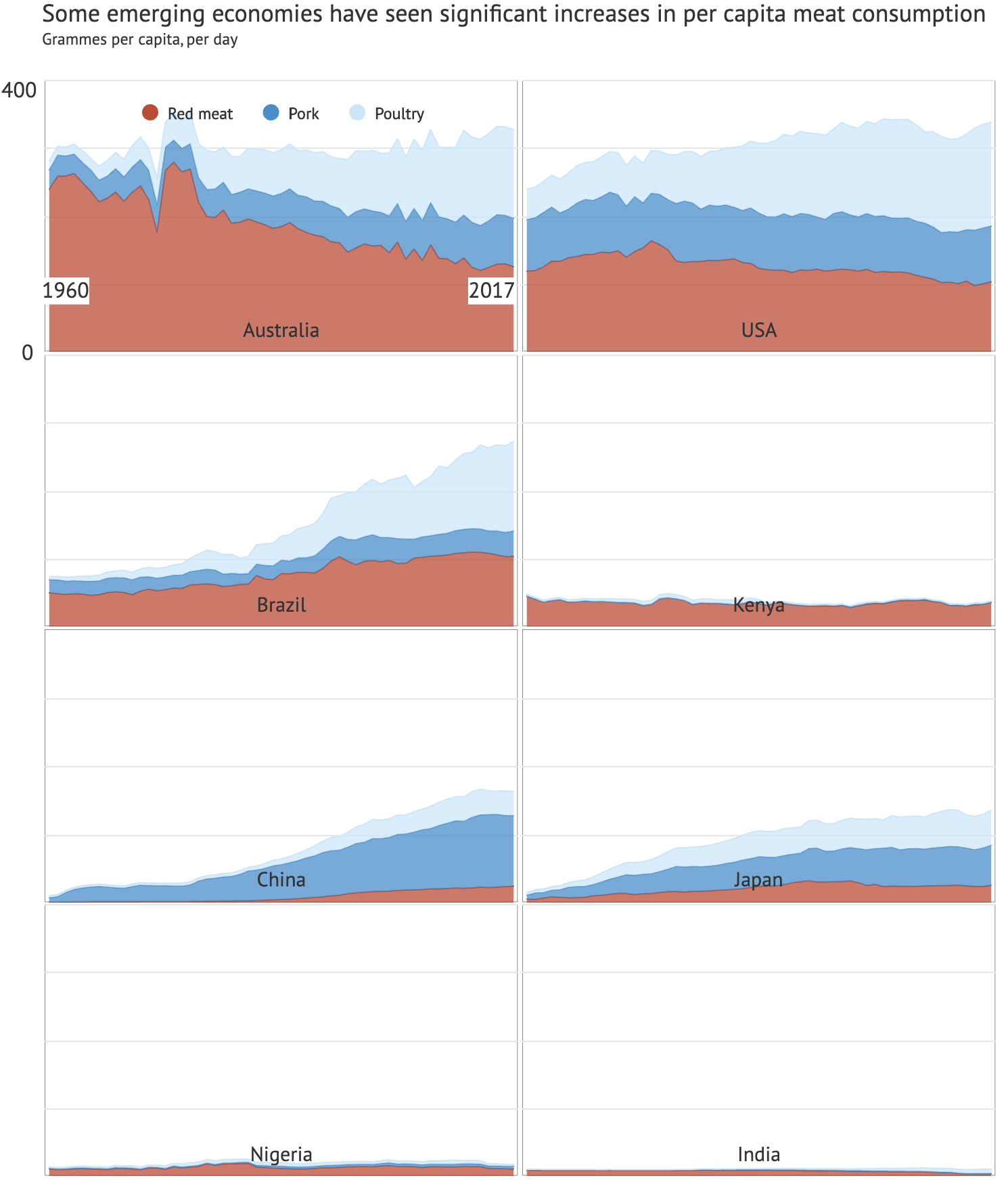

As people in western European nations, alongside countries such as the US, eat less red meat and dairy, inhabitants of emerging economies in Asia and South America tend to eat more of these products than they did in recent decades.

This trend can be seen in the chart below, based on FAO data for meat, with nations such as Brazil showing a significant increase in per-capita consumption while the US and Australia remain fairly steady.

Based on his analysis – which stretches from 1961 to 2013 – Bentham notes:

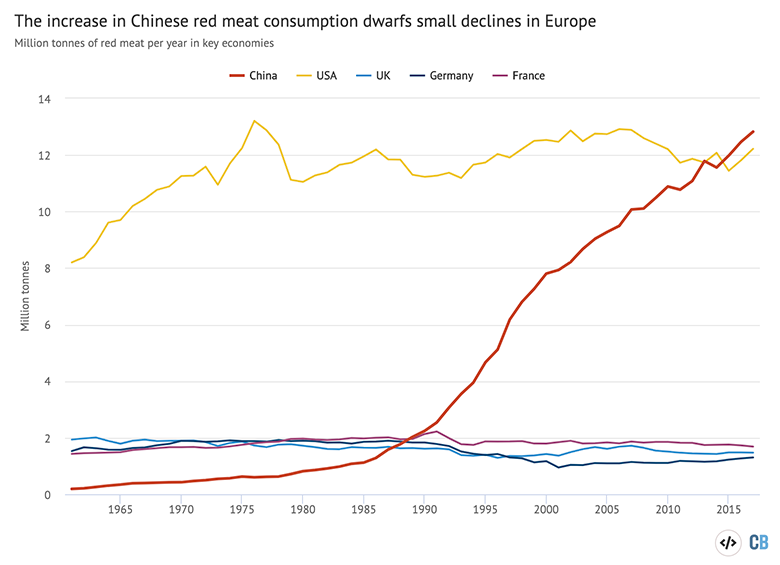

“The [per-capita] decrease in the west is not huge – and is not as large as the increase in China, South Korea and Japan, and then there’s just the fact that there are so many more people in East Asia than in the whole of the west.”

Meat and dairy consumption have been considerably higher in Latin America than Africa and Asia for some time, with beef widely seen as a staple for the poor as well as the rich due to comparatively low production costs.

In Brazil, where the beef industry has a particularly high environmental impact and farming is the largest cause of national emissions, one study described discussions in the country of the diet-climate link as “marginal”.

Meanwhile, for many people eating large amounts of meat is still not an option, as evidenced by the fairly low rates of consumption in African countries. However, growing populations alone are still expected to result in nations such as Kenya and Nigeria significantly increasing their demand in the coming decades, even if per-capita intake remains low.

Researchers have noted that, when it comes to diets, there is no “one-size-fits-all” approach, arguing that many poorer nations will likely need to increase their dietary emissions to ensure their populations are eating healthily.

One recent study found that in 36 countries, home to around 2.5 billion people, the adoption of EAT-Lancet’s “planetary health” diet would increase agricultural emissions per capita by over 10%.

Dairy plays a big role in this, as it is both emissions-intensive and also recognised as important for preventing stunted growth in children.

In a relationship that has been dubbed “Bennet’s law”, when people become wealthier their rising incomes tend to correlate well with rising meat and dairy consumption. Benton tells Carbon Brief:

“Eating meat for most societies around the world has been a high status activity…So there is quite a kind of anthropological determinism in that the more you develop from an economic perspective the more likely you are to eat more meat.”

However, Springmann notes this transition is not necessarily inevitable:

“As countries become richer, food industries become more interested in those countries, and they run heavy marketing campaigns to get people hooked on those cheap and processed food products.”

Benton agrees this trend is not “set in stone”, pointing to the example of India as a nation that, for various cultural, religious and economic reasons, has retained low levels of meat consumption. (It is, however, the world’s largest milk producer and its livestock sector is responsible for more emissions than road transport.)

Devinder Sharma, a food and trade policy analyst, says that, while India is “blessed” with a largely plant-based food tradition, he attributes rising emissions from emerging economies to the imitation of both western diets and industrial farming practices. “The problem is mostly coming from western countries,” Sharma says.

“Gradually people are realising that a reduction in meat consumption is what is ideal for the world to survive…but that realisation is very slow,” he tells Carbon Brief.

Ultimately, the relatively small changes in western diets will likely not be sufficient from a climate perspective, especially if other nations continue increasing their consumption of meat.

This is, perhaps, especially true for China, where supporting meat production has been government policy in recent decades and almost a third of the world’s meat is consumed. Much of the growth in global beef consumption has been driven by China.

In 2016, some English-speaking media reported that the Chinese government’s new dietary guidelines aimed to reduce meat intake by half, in a move backed by celebrities and welcomed by campaigners.

However, Li Shuo from Greenpeace East Asia tells Carbon Brief that much of the hype is “unfortunately based on misleading interpretation of the policy”. He adds: “I did not observe any change that the guidelines created for the dinner table.”

When will the world reach ‘peak meat’?

Amid discussions around diets and climate change, the concept of “peak meat” has emerged, with speculation around when the world will arrive at such a point.

In a letter to Lancet Planetary Health last year, scientists called for governments to “declare a timeframe for peak livestock” and incorporate this into their updated nationally determined contributions (NDCs) to the Paris Agreement.

They argue that, in wealthier nations, cutting demand for livestock products and not simply outsourcing production to other countries will be essential to create “Paris-compliant agriculture sectors”.

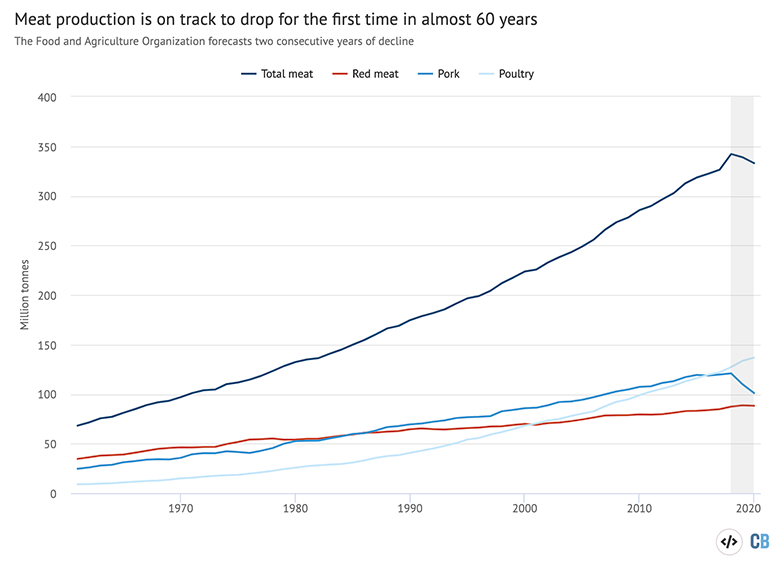

There is evidence that peak meat may be close. FAO forecasts suggest that in an unprecedented trend, after falling last year, meat production is once again on track to drop in 2020. Meat consumption per capita is projected to fall by nearly 3%.

While red meat production is set to decline slightly, with a 0.8% drop in beef, the main driver of this change is falling pork production, as the chart below indicates.

However, this projected decline comes in unusual circumstances. Meat production has been hit twice this year, first by the outbreak of African swine fever which was already devastating pig farms in China and Vietnam and which has largely driven the fall in global pork output.

The other key event was the Covid-19 pandemic, which has disrupted all meat markets and supply chains due to labour shortages and facilities closing down temporarily.

The FAO did not specifically estimate the impact of coronavirus, but as the organisation’s chief economist Upali Galketi Aratchilage tells Carbon Brief:

“It is possible to think that meat production decline would have continued at the 2019 rate without the impact of the pandemic and that the pandemic aggravated it further.”

Demand for meat has also dropped alongside production, as reduced sales in the food service industry due to Covid-19 closures have only been partially offset by increases in retail sales.

Prior to the pandemic production of beef (the meat with the largest environmental footprint) was already slowing down, even in nations such as the US and Brazil. On a per-capita basis, global beef consumption peaked in the 1970s.

While this seems like progress towards achieving overall peak meat, Aratchilage adds that prior to the pandemic they did not anticipate a global drop in demand for all meat products:

“Our data do not indicate such a fall at the global level, though consumption declines are observed in a few specific countries.”

Dr Helen Harwatt, who led the call for “peak livestock”, tells Carbon Brief signs of changing consumer habits are promising, but would not be enough to bring about the changes required:

“Not only do we need changes to happen on a much larger and more rapid timescale than what market signals from a relatively small group of consumers alone can deliver, we need system level changes to be implemented.”

Can dietary guidelines help achieve climate targets?

Given the slow progress away from high-emitting foods, experts have concluded that interventions from official agencies and governments are likely to be necessary.

But despite the clear links between diets and climate change, fashioning policies in this area is still “politically toxic”, according to Simon Billing of the UK’s Eating Better, a coalition of civil society organisations.

This point is echoed by Jillian Semaan, who worked at the US Department of Agriculture during the Obama administration’s controversial attempts to encourage healthy eating in schools.

“Let’s be very honest, people do not like having their government tell them what to do,” she tells Carbon Brief:

Perhaps unsurprisingly, examples of targets being proposed by authorities to specifically reduce emissions from people’s diets are rare.

The EU’s recent “farm to fork” strategy indicated the importance of plant-based diets, but fell short of setting the targets proposed by NGOs.

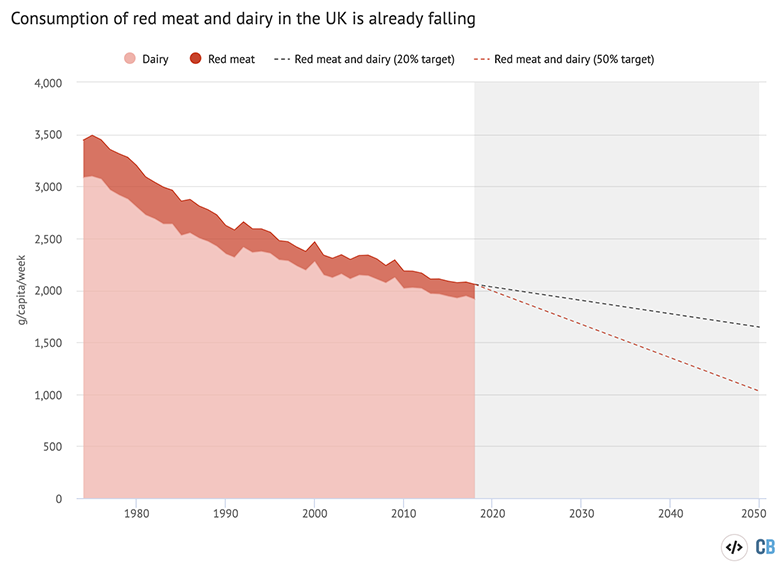

In its guidance on achieving net-zero emissions by 2050, the UK government’s Committee on Climate Change (CCC) recommends reducing consumption of “the most carbon intensive foods” – beef, lamb and dairy products – by 20%.

The CCC says this recommendation is in line with recent dietary trends in the UK, with the committee’s land analyst Indra Thillainathan saying this was chosen over another scenario in which red meat and dairy consumption was cut by a more ambitious 50%. (However, the 50% target still appears as part of the CCC’s “further ambition” scenario.)

The chart below shows that the CCC’s recommendations do indeed appear to be in line with trends in UK diets, based on self-reported surveying by the government.

Despite this, the CCC says current downward trends “are not likely to be sufficient” to deliver the required changes.

The UK government has accepted the CCC’s net-zero target, but it has been more ambivalent about the dietary guidance. In one BBC News interview, former climate minister Claire Perry described telling people to eat less meat as “the worst sort of nanny state ever”.

This attitude is not unique to the UK, with authorities in other nations, including Germany and Ireland, showing hesitance in advising people to eat less carbon-intensive foods. Meanwhile, US vice president Mike Pence recently accused his Democrat opponents of trying to “cut America’s meat” as part of their proposals for tackling climate change.

Billing tells Carbon Brief this is is partly to do with the fact that awareness among the public of the need for dietary changes to achieve climate targets is still fairly low:

“Politicians understand that I think and, therefore, they don’t like talking about it. We know in the climate community that it has to happen if…you’re going to get anywhere near net-zero.”

However, many governments already “tell people what to eat” via national dietary guidelines. Many researchers, NGOs and the FAO itself have identified these guidelines as an important opportunity to substantially reduce emissions.

As of 2016, an FAO report found just four countries – Germany, Brazil, Sweden and Qatar – specifically referencing environmental concerns in their official dietary guidelines. Since then, more including Canada, Norway and Switzerland have joined the list.

Others, including the UK, France, the Netherlands and Estonia, had “quasi-official” guidelines produced by government-affiliated entities that mentioned the environment.

Meanwhile, attempts to incorporate such considerations into US and Australian guidelines have been shelved after opposition from the meat industry and farmers.

Instead, while dietary guidelines tend to vary depending on the culture they emerge from, health is generally seen as their priority. Fortunately, as Benton tells Carbon Brief:

“There is a commonality between what is a healthy diet and what is a low-footprint diet, primarily because the healthier diet is one that is richer in fruit and vegetables and lower in animal products.”

The CCC’s Thillainathan notes that the UK government’s healthy eating guidance, the EatWell Guide, recommends a much higher level of reduction than the CCC’s guidance, calling for an 82% cut from current levels of beef and lamb consumption.

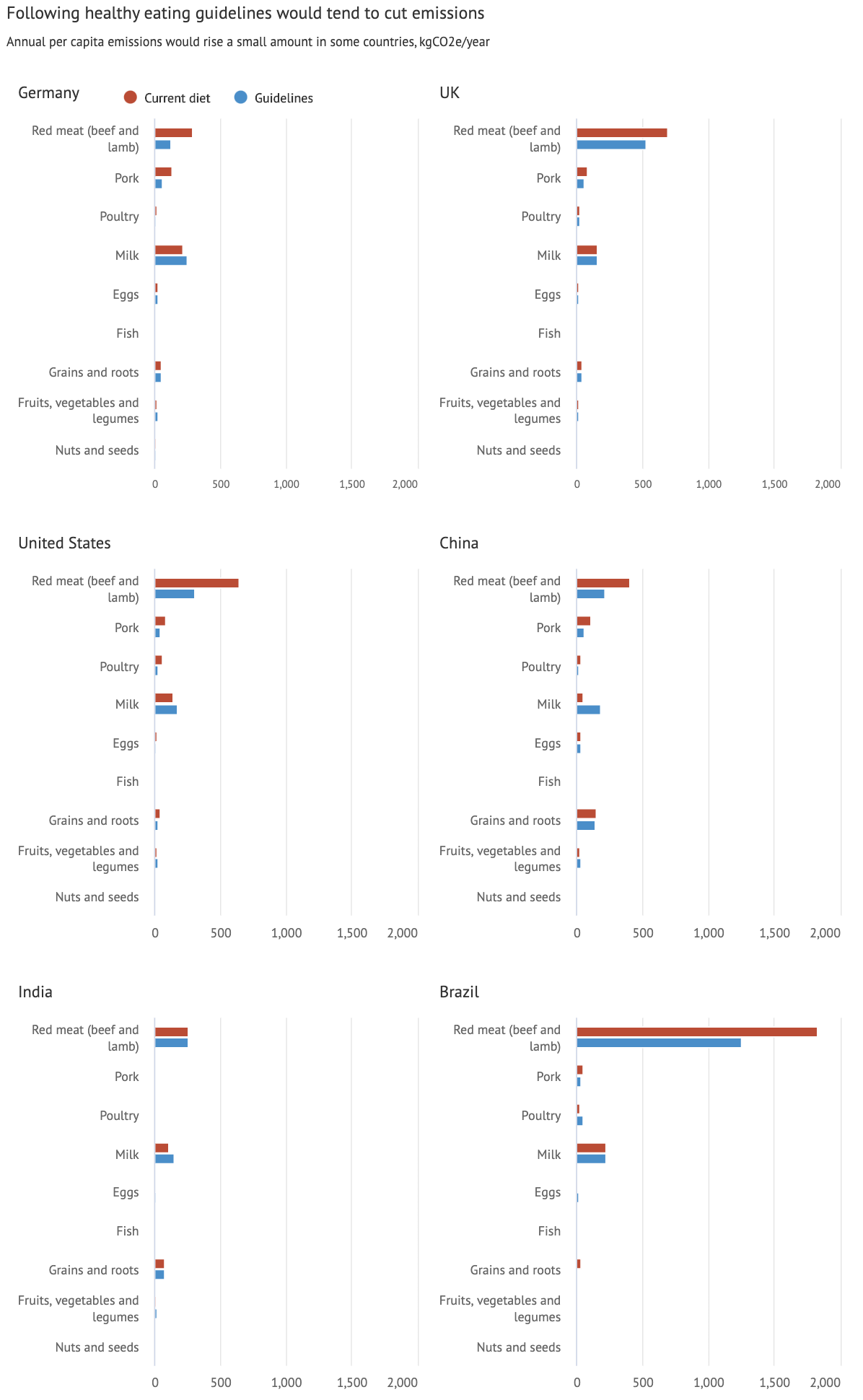

A recent study led by population health scientist Dr Marco Springmann, found that the global implementation of dietary guidelines would cut food-related emissions on average by 13% – equating to 550MtCO2e – across all 85 nations with such guidelines.

Adoption of World Health Organisation dietary recommendations would be associated with a similar reduction in emissions of 12% on average, the study found.

The impact that national guidelines could have on emissions, as well as the dominance of red meat and, to a lesser extent, dairy in the footprints of each nation, can be seen in the chart below. Often, following government guidance would result in dairy emissions rising.

Based on Springmann’s analysis, the blue columns show the total emissions per capita if everyone followed the guidance, compared to estimates of emissions from consumption in 2010, in red.

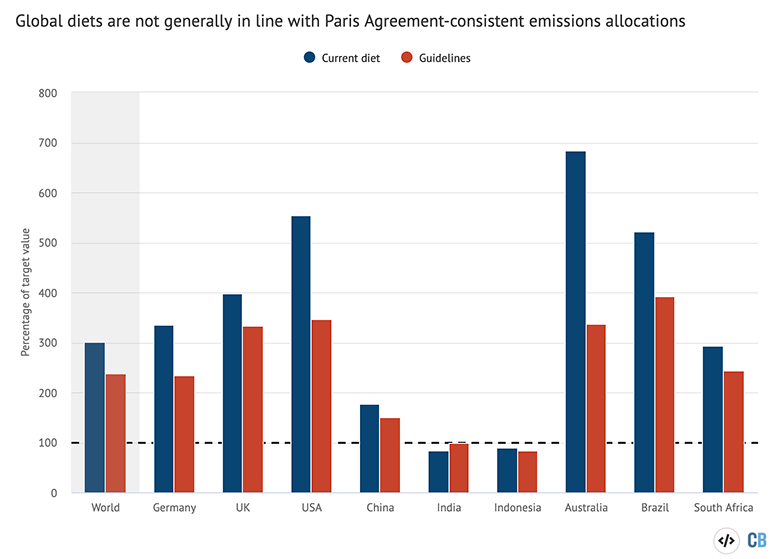

Crucially, while existing guidelines may cut emissions, they are far from being in line with the temperature rise targets set out in the Paris Agreement.

Dr Hannah Ritchie conducted a similar analysis in 2018 and calculated per-capita emissions from food if everyone in a handful of major economies followed national dietary guidelines. She compared these figures to the global per-capita emissions required overall to achieve the Paris Agreement targets. She tells Carbon Brief:

“If we don’t see massive improvements in emissions factors [kgCO2e per unit of food production] or emissions from agriculture over time, by 2050 [food] would exceed the total economy-wide budget for 1.5C and not far off 2C, so there would be no room in the budget for anything else apart from food.”

Springmann and his colleagues came to a similar conclusion. For each country, they allocated a national emissions budget to food production under a pathway in line with 2C of warming. They then modelled full adoption of national dietary guidelines finding these, on average, to exceed the budget allocations by 140%.

Only 11 nations had dietary guidelines consistent with the 2C pathway.

The gap can be seen for a handful of key economies in the chart below, with the red bars indicating the emissions from guideline-adherent diets and the dotted line indicating the 2C-consistent allocation for food in 2050.

Finally, there is the problem of adherence. Not only are global nutritional and climate goals currently incompatible, but dietary guidelines are simply not being followed, as Ritchie tells Carbon Brief:

“Some criticise the guidelines – that they are not going far enough – but the point is that we are still way off those guidelines.”

Springmann says that without policy support, providing information about food is not enough to encourage a meaningful shift in people’s diets:

“Just telling people not to eat this or eat that, doesn’t seem to work at all. Only if you implement that information and accompany it with actual policies that speak to that can it result in some difference.”

What else can governments do to alter diets?

A review in 2015 of efforts to shift consumption patterns away from meat, as well as other foods with high environmental impact, such as palm oil, found that such interventions were “extremely thin on the ground”.

Various stakeholders tell Carbon Brief this is still largely the case today, with many of the policies proposed by experts, including meat taxes and carbon labelling schemes, failing to find widespread support from policymakers.

A review of meat consumption trends in Science concluded: “The existence of major vested interests and centres of power makes the political economy of diet change highly challenging.”

Behrens agrees that beyond widespread unwillingness from politicians there are also many agricultural and industry groups that are “heavily invested” in the current system and unwilling to change.

However, while much of the progress in this area has been slow, Benton says the world could be on the cusp of a significant shift:

“If you think back to tackling other issues, such as smoking or Covid-19, you have a period where information grows and nothing happens, then suddenly something…causes a radical shift in opinions and then policy happens.”

To incentivise a “race to the top” in the food industry, the CCC has called for measures to increase the sector’s accountability and introduce monitoring and reporting standards for supply chain emissions.

Meanwhile, groups including Eating Better in the UK and the Green Protein Alliance in the Netherlands are advocating for changes to every aspect of the food system, which they say could influence people to take up more climate-friendly diets.

What follows is a selection of some of the policy instruments that have been proposed by scientists, NGOs and other stakeholders as key to driving substantial changes in global diets.

Taxes and subsidies

A carbon tax is viewed by many as a core component of efforts to curb dietary emissions, by raising the cost of high-emissions food and discouraging people from buying it.

One study concluded that “optimal” taxation could cut emissions by 109MtCO2e, a reduction of 1.2% in food-related emissions globally, mostly due to reduced beef consumption.

Germany, Sweden and Denmark are among nations that have discussed “meat taxes”. The investor network Farm Animal Investment Risk and Return (FAIRR) has said such measures are “increasingly probable” due to Paris Agreement targets.

Dr Sinne Smed from the University of Copenhagen has conducted research into the impact of taxes on consumption, notably Denmark’s world-first “fat tax”, as well as the potential benefits of a carbon tax on food. She tells Carbon Brief:

“The idea of implementing a tax is that the prices should reflect the full cost of producing the food that you eat. If a food has high emissions then you should pay more because you pay the cost to the climate.”

Another study found that increasing the cost of beef by 40% and milk by 20% would be enough to account for their climate impact.

As with other taxes on foodstuffs, such as the UK’s sugar tax, the Danish tax on saturated fats faced significant opposition. It was reversed after less than two years.

Smed says that such proposals tend to face pushback in part because they are seen as being unfair to poorer people, who would no longer be able to afford certain foodstuffs.

However, to combat this researchers have proposed a system by which poorer households are offered rebates and revenues are used to fund programmes to promote plant-rich diets.

Other price-based mechanisms to change people’s diets include removing subsidies for livestock farming, which currently cost governments in the EU and US billions every year, and subsidising plant-based alternatives instead.

A man browses US beef on a shelf at a discount store in Seoul, South Korea. Credit: Newscom / Alamy Stock Photo.

Public procurement

In 2017, the German environment ministry faced criticism when it announced it would only be serving vegetarian options at official functions.

Despite the backlash, “public procurement” measures are seen by many as a socially acceptable way to normalise the consumption of more plant-based meals with lower environmental footprints. Wellesley tells Carbon Brief:

“You might be able to change the food environment in schools, hospitals, government buildings and public buildings. As a means of creating new social norms, [that] is quite powerful.”

Sustainable procurement has seen some success in recent years, with various universities, schools and cities pledging to align their purchases with climate-friendly diets.

- Interactive: How climate change could threaten the world’s traditional dishes

- Interactive: How climate change shapes food insecurity across the world

- Meat and dairy consumption could mean a two-degree target is “off the table”

- Grass-fed beef will not help tackle climate change, report finds

- Farming overtakes deforestation and land use as a driver of climate change

In 2017, Portugal approved a law that ensures all public canteens provide vegan options, while recent legislation could make Maryland the first US state to set emissions reduction targets for food purchases.

According to UNEP, public procurement has “enormous purchasing power”, accounting for around 12% of GDP in Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries, and “up to 30% of GDP in many developing countries”.

Acknowledging there are “no silver bullets”, the UK’s CCC has suggested various ideas that could be implemented to encourage a dietary shift. Thillanaithan says the best place to start is probably with “low-regret, low-cost measures”, such as public procurement that cuts out meat and dairy products.

Behavioural ‘nudges’

Besides removing meat and dairy from public places, other behavioural “nudges” have been suggested as “low-regret, low-cost” ways to change diets that are relatively acceptable to the public.

Nudges include everything from reorganising products in supermarkets to adjusting meat portion size in cafes and restaurants.

The Behavioural Insights Team, a former UK government unit, emphasised the importance of normalising sustainable diets in a report titled “a menu for change”:

“We enjoy eating meat and dairy in part because they are cheap…their consumption is normalised in our culture…they are heavily marketed; and nudged upon us…through myriad aspects of the choice environment in supermarkets and restaurants.”

This approach is given weight by the work of Ayse Allison, a PhD student at University College London, who has studied the psychology of meat consumption. She tells Carbon Brief that one of her conclusions was that people eat meat simply “because it’s there”.

However, Professor Sir Charles Godfray, a population biologist and director of the Oxford Martin School, tells Carbon Brief he is concerned that governments might see nudges as “all they need to do”:

“If we are serious about [a] 1.5C or 2C world, we need to do much more than can conceivably be brought about by nudges and these subtle changes.”

He adds that while governments can “avoid headlines about it in the tabloid newspapers” by sticking to small interventions, they are “fooling themselves if they think that’s going to solve the problem”.

Education and carbon labelling

Education programmes and campaigns such as “meatless Mondays” have the potential to drive change, although it is difficult to assess how much impact they have.

In some nations, this might mean pushing back against the incursion of “western” food products. For example, Sharma says in India there have been considerable civil society efforts to promote the consumption of “core” national cereals, such as millets.

Japan is another rare example of a nation that has had some success in limiting meat consumption despite economic growth, with the government promoting a traditional diet of fish, vegetables and rice partly in a bid to preserve self-sufficiency in food.

Carbon labelling is a form of awareness-raising that has been trialled extensively by food companies and supermarkets, and, according to research by the Carbon Trust, is popular with the public.

Dr Pernilla Tidåker from the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, who was involved in establishing a widely publicised labelling system in Sweden in 2009, tells Carbon Brief accounting for exact emissions from each food product can be “difficult and costly”.

They opted instead for a “climate certification” scheme in which, for example, pork and dairy products are certified if they are from farms with emissions 15% below average.

While there is evidence that consumers find precise carbon footprints difficult to interpret, research has demonstrated that simple carbon labels do encourage people to choose low-emissions foods.

However, research has also indicated that for palm oil, a product that can be a major driver of land-use change and emissions in Southeast Asia, consumers still do not generally recognise sustainability labels, despite extensive campaigning by NGOs.

Language on labels could also have a big impact. One World Resources Institute study found that changing labels from “meat-free” to “field-grown” increased sales by 17%.

Trade deals

On an international scale, trade flows could have a role to play in ensuring that the food people eat does not come with a significant emissions cost.

Garnett highlights trade as a “really important” influencer of global diets. She tells Carbon Brief that plans for the UK’s post-Brexit trade deal are a good example of this, particularly the extent to which “influxes of cheap, terrible meat from the US and places like that” are allowed in:

“That’s going to keep prices low and it’s going to either stimulate or at least maintain high levels of consumption.”

Producers of animal products in high-income countries “actively lobby their governments and trade ministers for improved access to new and emerging markets to support increased production and exports”, according to recent research.

Similarly, trade agreements to cut tariffs on agricultural goods have been linked to rising meat consumption in the “global South”.

Professor Sir Charles Godfray was interviewed by Daisy Dunne.

-

In-depth Q&A: What does the global shift in diets mean for climate change?

-

In-depth Q&A: What the global shift in diets means for climate change