In-depth Q&A: How the UK plans to cut industrial emissions by two-thirds

Josh Gabbatiss

03.19.21Josh Gabbatiss

19.03.2021 | 1:53pmFactories and industrial hubs across the UK should cut their emissions by two-thirds over the next 15 years under the government’s new plan for low-carbon industry.

It marks the first in a series of strategies expected from the government this year, setting a course for the nation’s 2050 net-zero emissions goal.

Industries including steel, cement and chemicals produce 16% of UK emissions and rely on processes that are among the most difficult and expensive to decarbonise.

This makes firm sectoral targets, support for new technologies and clear signals to businesses all the more important, experts tell Carbon Brief. This piece highlights key points from the 170-page strategy and areas of policy that still remain unclear.

- Is the strategy ambitious enough for net-zero?

- Is the government committing enough money?

- What is the plan for achieving net-zero steel production?

- Is there a strategy for decarbonising cement?

- What is the role of CCS and hydrogen?

- Is there a clear plan for carbon pricing?

- How important are efficiency and consumer choices in the plan?

Is the strategy ambitious enough for net-zero?

The industrial decarbonisation strategy was announced by the government as an “ambitious blueprint to deliver the world’s first low-carbon industrial sector”.

Its headline aim is that emissions will need to fall by at least two-thirds by 2035 and by at least 90% by 2050, relative to 2018 levels, to be on track for the UK’s net-zero target. This is roughly in line with guidance from government adviser the Climate Change Committee (CCC).

The CCC sees emissions from “manufacturing and construction” – roughly analogous to the government’s definition of industry – falling 70% by 2035 and 90% by 2040 from 2018 levels in its central net-zero pathway.

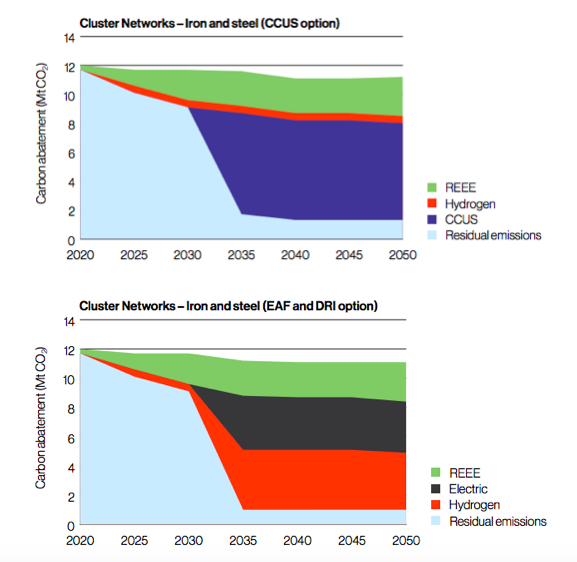

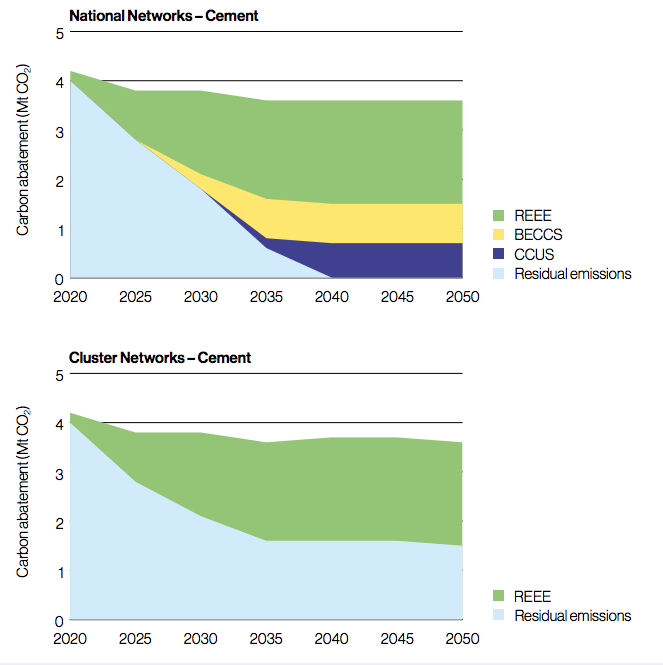

The charts below indicate two broad scenarios modelled by the government. The main distinction in the pathways is whether carbon capture and storage (CCS) and hydrogen are available across the country (“national networks”) or only at industry clusters in places such as Teesside and South Wales, which account for half of industrial emissions (“cluster networks”).

Even in these scenarios, the government expects there to be some remaining carbon dioxide (CO2) even in 2050, shown as “residual emissions” in the charts below. This creates demand for expensive “negative emissions” elsewhere.

The government sets out its principles at the start of the report, stating:

“Over the long run, we believe carbon markets are best placed to determine the most cost-effective pathways to decarbonisation. But industry faces a range of well documented barriers to clean growth, and government efforts so far have not provided the framework needed to make decarbonisation viable. We will change the policy landscape to overcome these issues.”

It includes a handful of targets including 20 terawatt hours (TWh) of low-carbon power in industry replacing fossil-fuel sources and 3m tonnes of CO2 (MtCO2) captured by 2030.

There is also a commitment to “consider the implications” of the CCC’s recommendation to achieve net-zero steelmaking by 2035.

However, there is no commitment for cement, despite the committee calling for a similar target for the industry to achieve net-zero by 2040.

Roz Bulleid, deputy policy director at the thinktank Green Alliance, tells Carbon Brief that while it is “encouraging” that emissions reductions described in the strategy are similar to CCC’s guidance, it would benefit from firmer commitments for key sectors like steel:

“[For] sectors where the technology is emerging I think some bolder targets would be welcome…it would be a really strong signal of government intent and help focus minds.”

Questions remain unanswered around the business models and incentives the government has in mind. These would give industries confidence to make the shift and enable investors to place a value on industrial decarbonisation.

The idea is that beyond up-front support for zero-carbon industrial kit, companies will need bankable ongoing markets for cleaner products in order to justify the investment.

Tim Lord from the Tony Blair Institute for Global Change says that while there are mentions of supporting low-carbon technologies and long-term targets, there is much less on these “middle bits”. The government says it will have details of ways to support business models for CCS and hydrogen ready this year and will implement them in 2022.

The less good: HMG funding for net zero industry is important, but long-term business models are what really matters. Looks like the strategy will be light on detail on carbon pricing, competitiveness, decarbonising steel etc. More a set of ambitions than a plan. (3/)

— Tim Lord (@timbolord) March 17, 2021

Richard Howard, research director at Aurora Energy Research, agrees that while it is “still useful to have an overarching strategy”, there remains plenty of uncertainty:

“If you’re about to make the investment decision on something that either is or isn’t consistent with this strategy, how does this strategy influence you? Well, it gives you a general direction of travel…but it doesn’t really give you precise details.”

Earlier this month the House of Commons Public Accounts Committee concluded that “at present, there is no coordinated plan” for achieving net-zero from the government.

In a blog post, Dr Jonathan Marshall, head of analysis at thinktank the Energy & Climate Intelligence Unit (ECIU) wrote that more “vague” language would not do much to assuage concerns, although he noted that the strategy hinted at greater understanding within government.

A number of relevant strategies are expected in the coming months – including ones focusing on hydrogen, heat and buildings and transport – as well as a net-zero review from the Treasury and, ultimately, a net-zero strategy before the COP26 summit.

Is the government committing enough money?

Industrial decarbonisation is expected to require significant investment. As Lord points out, “it’s always going to be more expensive to burn fossil fuels, capture and bury the CO2 than it is just to burn fossil fuels”.

The CCC estimates that getting manufacturing and construction on track for net-zero will require investments of around £1bn each year in 2030, £2bn in 2035 and £4bn through the 2040s.

Money to fund this transition can come from businesses as well as government, and the document is clear that costs should be shared between industry, consumers and taxpayers.

The main funding pledge in the new strategy is the allocation of £171m from the industrial decarbonisation challenge fund, which was initially announced in 2019.

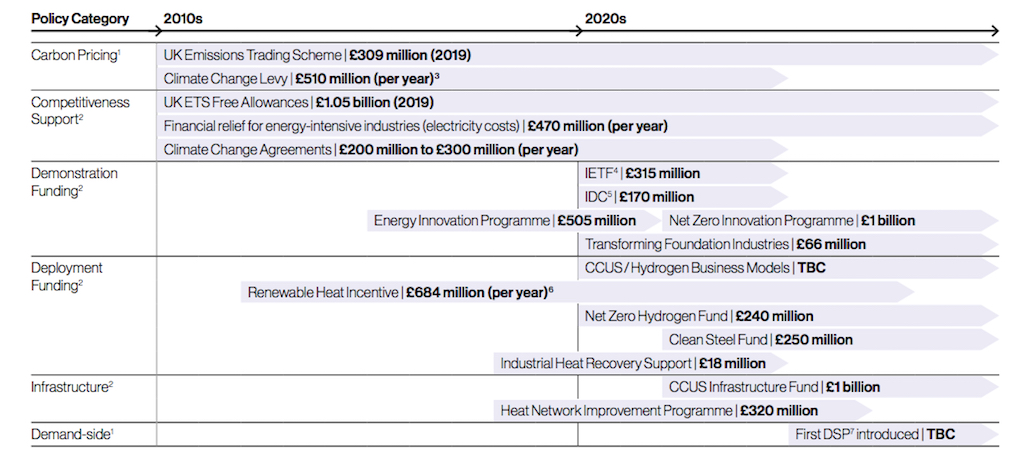

The government also has other relevant funds in the pipeline such as a £240m net-zero hydrogen fund and a CCS infrastructure fund worth £1bn. Details of the investment needs from both government and businesses can be seen in the timeline below.

Alongside the industrial strategy, the government announced the 429 recipients of its £932m public sector decarbonisation scheme for hospitals, schools and council buildings.

This funding was originally announced last summer as part of the government’s “green recovery” stimulus efforts, alongside the recently scaled-back “green homes grant”.

Much of the response to the new strategy focused on the scale of funding. Comparisons were made by opposition Labour politicians between the relatively small “decarbonisation challenge” fund and the billions being allocated to hydrogen in other European countries.

Bulleid tells Carbon Brief that, compared to the CCC’s £1bn by 2030 figure, “there isn’t much money committed here”.

With details still to come on revenue mechanisms to support business models for both CCS and low carbon hydrogen (see next section), Lord says that clarity is key:

“You could, theoretically, do it with…no taxpayer investment at all if you get the incentives right for people, but then you’ve got to be quite aggressive on regulation, on carbon pricing and on other tools.”

However, Bulleid expresses concerns about the lack of public funding, telling Carbon Brief the government could have made more commitments to the industrial energy transformation fund (IETF) or other targeted funds. She says:

“If they are going to make up most of the money through the business models for hydrogen and CCS that would then be a concern to see so much of the funding swung that way”.

What is the plan for achieving net-zero steel production?

The UK’s main primary steel production facilities – the blast furnaces in Port Talbot and Scunthorpe – currently produce 15% of the UK’s industrial greenhouse gas emissions.

Shifting to a zero-carbon steel sector is therefore “essential to the decarbonisation story of UK industry”, the strategy says.

There are various options available for “green steel” including using electric arc furnaces – which are used to produce “secondary steel” from recycled scrap metal – instead of conventional fossil fuel-based blast furnaces, as well as using CCS and hydrogen.

The charts below show two different scenarios outlined by the government, with different mixes of these technologies, largely depending on the availability of hydrogen, which is deemed a cheaper option.

The government has attracted criticism because, while nations including Germany and Sweden are pushing forward with low-carbon steel trials using hydrogen, the UK is falling behind.

Two years ago, the government announced a £250m “clean steel fund”, but despite calls to bring it forward, it is not currently set to provide any money until 2023.

While the strategy mentions the CCC’s proposed 2035 net-zero date for steel, the government does not go further than saying it will “consider the implications” of setting such a target.

The levels of ambition set out in the new Industrial Decarbonisation Strategy in relation to industry/the public sector are encouraging but the document is woefully light on detail (and downright opaque when it comes to decarbonising steel) and no new funding has been announced.

— Matthew Pennycook MP (@mtpennycook) March 17, 2021

This industry has been in the news due to the controversy over plans for a new coal mine in Cumbria, which would produce coking coal for use in steel production.

Supporters of the mine argue this type of coal will continue to be needed for some time, whereas the CCC timeline implies a much shorter lifespan for the development.

Following international pressure, the government has belatedly ”called in” the local authority’s decision to allow the project to go ahead, meaning a public inquiry will be held and a final decision made by the communities secretary. Business and energy secretary Kwasi Kwarteng has said that there are “very compelling reasons” not to open the mine.

However, the strategy does not entirely rule out the continued use of coking coal, stating:

“This strategy takes a technology-neutral approach and so does not rule out the use of coking coal in an integrated steel making process together with CCUS as a net-zero compliant option going forward.”

In a letter to communities secretary Robert Jenrick in January, CCC chair Lord Deben warned against the opening of the Cumbria mine. He noted that coking coal should only be used in steelmaking beyond 2035 “if a very high proportion of the associated carbon emissions is captured and stored”. He added:

“Coking coal use in steelmaking could be displaced completely by 2035, using a combination of hydrogen direct reduction and electric arc furnace technology.”

Is there a strategy for decarbonising cement?

Half of the emissions from traditional cement production come from the “calcination” of limestone, which produces CO2 as a by-product and therefore can only be decarbonised using CCS.

Cement accounts for around 6% of UK industrial emissions. Unlike steel and other major industries, many cement sites are not located in industrial clusters, something the strategy identifies as a “significant challenge”.

This means that in scenarios where it is not feasible to install CCS infrastructure beyond industrial hubs, it becomes much harder to eliminate cement emissions. This can be seen in the charts below, which shows significant residual emissions in the “cluster networks” outlook.

Although there is no discussion of a target, in line with the CCC’s proposal to make cement a net-zero industry by 2040, in the “national networks” scenario above the industry does reach zero emissions by 2040, through a combination of CCS and efficiency improvements.

What is the role of CCS and hydrogen?

The strategy relies heavily on the widespread deployment of both low-carbon hydrogen and CCS to cut emissions from fossil fuel-reliant sectors. As it stands, both of these technologies are barely used in the UK, with CCS, in particular, having been subject to a string of failed government attempts to get it off the ground.

The document notes that the government will need to play “an active role in overcoming market failures” and share the “risk and costs of scaling up deployment” of these technologies.

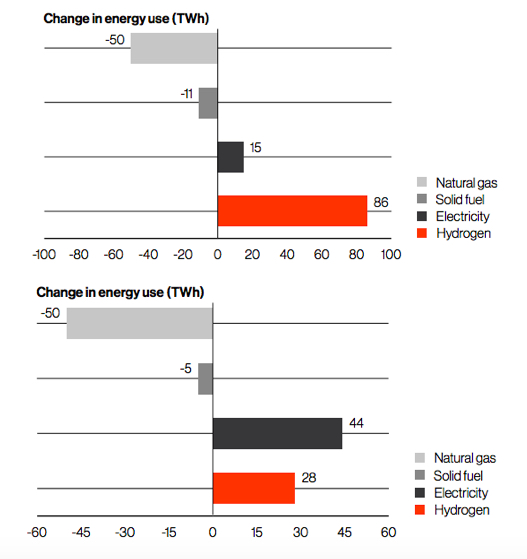

The charts below show how industrial energy shifts play out in different modelling scenarios, with gas use falling dramatically in both cases.

Hydrogen takes a particularly large role in the “national networks” outcome (top), contributing up to 86TWh of energy by 2050. This is the equivalent of a quarter of the nation’s entire electricity demand today.

In the “cluster networks” pathway, electrification plays the larger role, because the infrastructure does not emerge to provide areas outside of industrial clusters with hydrogen.

While green groups criticised the strategy for relying too much on CCS, the government is emphatic that without it “emissions from current industrial processes cannot be reduced to levels consistent with net-zero”.

This is consistent with the CCC’s message that “CCS is essential to achieving net-zero”.

In the report’s modelling scenarios, there is 3MtCO2 captured per year using CCS in 2030, and 8-14MtCO2 per year in 2050. The government says it will support the deployment of 3MtCO2 worth of CCS at industrial sites by 2030.

It has previously committed to 10MtCO2 of CCS by 2030. The remaining 7Mt could come from CCS used in the electricity sector, for example in gas or biomass-fired power plants.

“My question there would be, OK where are the business models?” says Lord. This is a wider issue arising from the report, which does not set out a clear plan for encouraging private investment in these technologies.

“To do anything relating to CCS or hydrogen it’s hard to know what that is going to look like even in two years time,” says Howard.

Howard also tells Carbon Brief that while their strategies are not fully formed either, the billions committed to hydrogen in nations like France and Germany are likely to draw the eyes of businesses:

“If you’re looking across Europe and thinking ‘where should I play?’, at the moment the UK’s position isn’t that clear, so there’s a risk that people focus elsewhere initially.”

The government says it plans to finalise its ideas for industrial CCS and hydrogen business models in 2021 and to implement them in 2022. The CCS approach will be based on the contracts for difference that have helped promote wind power in the UK.

This year the government says it will look into policy options to encourage businesses to switch from fossil fuels to hydrogen, as well as electrification and biomass (primarily with CCS) technologies. More details are also expected in its upcoming hydrogen strategy and a biomass strategy in 2022.

Is there a clear plan for carbon pricing?

The UK’s carbon pricing system has been left up in the air following Brexit, with a UK emissions trading system (UK ETS) technically in place but much of the detail still unknown.

The strategy provides some additional details, stating that the cap on the overall amount of emissions allowed, “will be aligned with the UK’s net-zero ambition by January 2024”, reflecting the recent energy white paper’s commitment to implementing the “world’s first net-zero carbon cap and trade market”.

This year, the government will carry out a review of the UK ETS, in which it will explore whether to expand the scheme beyond the existing participants in domestic aviation, power generation and heavy industry. The Daily Telegraph reported this week that it could be expanded to include agriculture.

The government will also assess the continued use of free allowances, which currently enable big polluters to release some emissions without paying anything and cost the government over £1bn a year in lost ETS revenues.

Free allowances are currently used to prevent “carbon leakage”, where activities or supply chains move overseas to escape emissions pricing.

The government said the current approach “may overcompensate for the risk of leakage, and…we want to ensure that carbon leakage policies are better targeted”.

It lists climate diplomacy, a “carbon border adjustment mechanism” and improving domestic productivity as actions it will consider to prevent leakage.

The idea of gradually phasing out free allowances was welcomed by experts as part of a long-term strategy to encourage industrial decarbonisation. A call for evidence has been issued on this topic.

How important are consumer choices and efficiency in the plan?

Beyond the headline-grabbing funding commitments and plans for “deep decarbonisation” of industry, there is some discussion in the strategy of measures to impact consumer choices such as adding carbon labels to products.

Such actions can “increase industry confidence in the profitability of decarbonisation and to support consumers to make low carbon choices,” the strategy says.

However, most of these proposals are confined to “calls for evidence” rather than firm policies, which Lord says “feels a bit can-kicking”.

“You’re not going to bank on having a big green steel market in the UK because the government is doing a call for evidence, so you need to get through those stages quite quickly,” he tells Carbon Brief.

There are also plans for more energy efficiency measures, which the strategy says could cut 4MtCO2e from industry by 2050, largely via heat recovery and equipment upgrades.

Bulleid tells Carbon Brief she is concerned such measures are being overlooked. “It makes so much more sense to reduce emissions wherever possible, before you start using technologies like CCS,” she says.

However, according to Howard, one of the biggest challenges here is not a lack of support, but simply raising awareness of incentives and funding routes to invest in energy efficiency – an issue highlighted in the strategy.