Robert McSweeney

17.11.2014 | 3:03pmA lot of the meat we eat is produced in a different country from the one we live in. A new study finds that greenhouse gas emissions from the beef, pork and chicken traded across borders have risen by 19 per cent in the past 20 years.

Not only might this affect diets of the climate-conscious, but a trend towards eating meat produced in a different country could make monitoring countries’ individual emissions a far trickier task, say the researchers.

Livestock emissions

Carbon dioxide is the biggest contributor to climate change, but other greenhouse gases such as methane and nitrous oxide play a role too. The methane and nitrous oxide produced by livestock, such as cows, pigs and chickens, account for around nine per cent of all greenhouse gases emitted worldwide.

When you include methane and nitrous oxide emissions from transporting the animals and producing their feed, this proportion rises to 18 per cent.

A new study, published in Environmental Research Letters, finds that although the majority of meat is eaten in the country where it’s produced, more and more meat is being exported.

So which country should be held responsible for the greenhouse gas emissions? The one where the meat is produced or the one where it’s consumed?

The researchers say the growing demand for internationally-traded meat makes it harder to regulate emissions from farming.

Emissions from trade slipping through the cracks

All existing national or international policies to limit greenhouse gases take account of emissions from within specific countries only. So if the UK imports a tonne of beef, for example, the greenhouse gas emissions from producing it are not counted in our inventory.

You might think the emissions would be counted by the country producing the beef, but that might not be the case. The researchers say it’s increasingly likely that meat is being imported from developing and emerging nations, which often have less stringent accounting of greenhouse emissions.

So the emissions from that tonne of beef may not be counted by either country, and instead may just ‘leak’ between the gaps in the system, say the researchers.

Beef the worst emitter, but others are catching up

Of the meat traded from one country to another, the study finds beef makes the biggest contribution to emissions, responsible for around three-quarters of the GHGs produced.

The research takes account of methane produced as livestock digest food (yes, farting) and the methane and nitrous oxide released as manure decomposes.

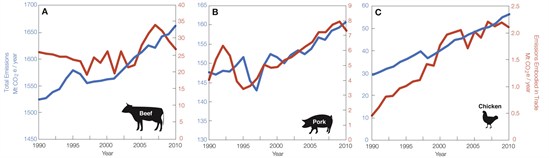

Emissions from traded pork (20 per cent) and chicken (six per cent) production are much lower by comparison, but are growing much more quickly. Between 1990 to 2010, the emissions from traded beef grew by around four per cent, while those from pork and chicken grew by 81 per cent and 360 per cent, respectively. You can see this in the charts below.

Emissions of methane and nitrous oxide from livestock in production of A) beef, B) pork and C) chicken. Graphs show total emissions per year (blue line) and emissions from traded meat (red line) in million tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent. Caro et al. (2014)

Where does the traded meat go?

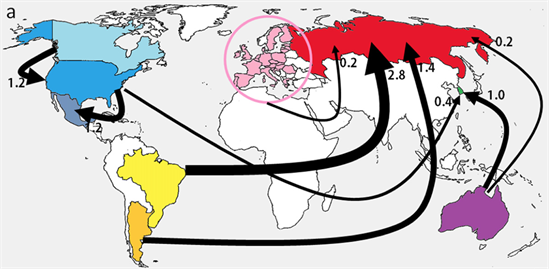

The researchers worked out which countries are responsible for the most emissions by mapping where meat is traded from and to.

The map below shows the main flows of livestock emissions around the world. You can see Russia (red) imports large amounts of meat from Brazil (yellow) and Argentina (orange).

Map of the largest emission imports and exports from meat production in 2010. Arrows show total emissions per year in million tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent. Caro et al. (2014)

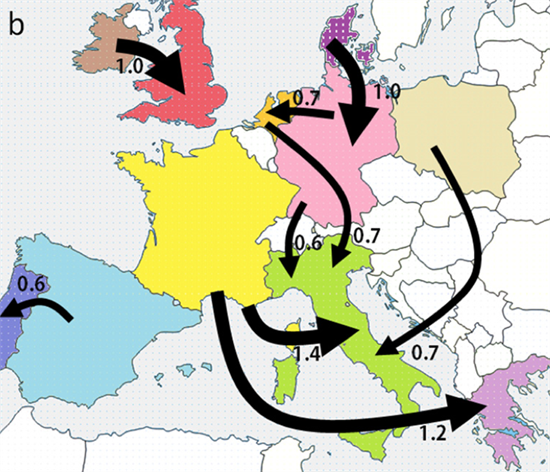

Emissions from meat traded within Europe are shown in the map below. Italy (green), for example, consumes a lot of meat produced elsewhere, particularly France (yellow) and Poland (beige). That means around a third of methane and nitrous oxide emissions from meat consumed in Italy in 2010 were produced in another country.

Map of the largest European emission imports and exports from meat production in 2010. Arrows show total emissions per year in million tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent. Caro et al. (2014)

Emissions hidden in traded meat could even encourage countries to import meat rather than produce it themselves, warn the authors. This new research highlights the risk that greenhouse gas emissions from meat production could be overlooked completely as global trade increases, complicating attempts to reduce emissions from farming.

Caro, D. et al. (2014) CH4 and N2O emissions embodied in international trade of meat, Environmental Research Letters, doi:10.1088/1748-9326/9/11/114005