Mat Hope

12.05.2014 | 3:20pmWe’re all used to the idea of flicking a switch to turn on the lights. But as greenhouse gas emissions rise, policymakers are going to have to find ways to make the whole economy – from cars to cookers – run on electricity too, a new report suggests.

While electrifying the global economy won’t be easy, the International Energy Agency (IEA) argues that it’s necessary if countries are going to prevent the world warming by six degrees.

The good news is, policymakers already have much of the necessary technology at their fingertips – they just need to learn how to harness its potential, the organisation says. Here’s an in-depth look at the IEA’s Harnessing Electricity’s Potential report.

Saving emissions

Much of the world’s electricity currently comes from burning fossil fuels such as coal and gas, and demand for electricity is rising. If governments are going to limit global warming to two degrees (the internationally agreed goal), they’ll have to find a less polluting way to generate electricity, the IEA says.

That would require a “massive reversal of recent trends”, the IEA’s report says. For the past 40 years, the carbon intensity of the energy system – the emissions associated with a unit of energy generated – has held steady. That’s largely because the world has continued to rely on fossil fuels such as oil, gas and coal to generate electricity.

To hit the two degree mark, the IEA’s analysis suggests the carbon intensity of electricity generation must decrease by 90 per cent by 2050. That means rolling out much more low carbon electricity from sources such as nuclear, wind, solar, and hydropower.

The graph below gives an idea of what is required for the world to move from an energy system that could lead to six degrees of warming, to one that should give a reasonable chance of curbing warming to two degrees.

The coloured chunks show how much each policy or technology contributes to getting carbon intensity down (in gigatonnes of carbon dioxide) to a level that would allow policymakers curb warming:

Currently, fossil fuels are responsible for about 68 per cent of electricity generation, and renewables 20 per cent. In 2050, those shares need to be reversed if countries are going to hit the two degrees goal, the IEA says – with renewables responsible for 65 per cent of electricity generation, and fossil fuels 20 per cent.

Such a “radical change of course is long overdue”, Didier Houssin, IEA director and one of the report’s authors, told a press conference.

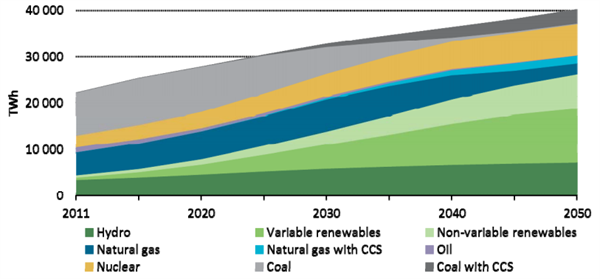

The graph below shows how much power will need to come from each source over the coming decades, according to the IEA’s analysis. As you can see, renewables (the green chunks) steadily increase their share, while fossil fuels (the grey and blue chunks) are increasingly squeezed out:

The IEA’s modelling suggests the world must:

- Add 92 gigawatts of solar photovoltaics each year. More than triple the 30 gigawatts added in 2012.

- Add almost 80 gigawatts of onshore wind annually – a 70 per cent increase on 2012’s building rate – and almost 16 gigawatts of offshore wind each year.

More nuclear power and some fossil fuel power with carbon capture and storage (CCS) will also be necessary, it says. But the IEA has scaled back the amount of energy it expects to get from these sources by 2050 due to delays in getting CCS demonstration plants up and running and cost overruns on recent nuclear projects.

New challenges

Moving from an energy system based on fossil fuels to one reliant on renewables isn’t straightforward, however. The IEA’s executive director, Maria van der Hoeven, said in a press release:

“[W]hile [electrification] offers many opportunities, it does not solve all our problems; indeed, it creates many new challenges”.

That’s because renewable electricity is more variable than power from fossil fuels as it depends on certain weather conditions (whether it’s sunny or windy, for example). But there are ways to get around this, the IEA says.

Most importantly, governments need to start to see the energy system as whole – from generation, to transmission, to use – rather than fragmented parts, according to the agency.

“A sustainable electricity system is a smarter, more integrated system”, another of the report’s authors, David Elzinger, told the press conference. To make a low carbon system work, policymakers must look at it as a whole rather than seeing fragmented parts, he argues.

For instance, countries need to make sure they upgrade the transmission grid at the same time as building a wind farm to make sure electricity can get from where it’s generated to where it’s needed. Likewise, governments should roll out initiatives such as smart meters that allow electricity supply and demand to be matched more easily.

These policies are “not fully being exploited” by governments at the moment, Elzinger says. The agency suggests that until they are, emissions will continue to rise and the world will be heading for six degrees of warming – with all the unsettling impacts that implies.