Human activity responsible for three out of four heat extremes, study finds

Roz Pidcock

04.27.15Roz Pidcock

27.04.2015 | 4:45pmA new study says 75% of extreme hot days and 18% of days with heavy rainfall worldwide can be explained by the warming we’ve seen over the industrial period.

In a future world with 2C warming above pre-industrial levels, almost all extreme hot days and 40% of heavy rainfall days will be down to rising temperatures, say the authors.

The new study, published today in Nature Climate Change, is the first to estimate how climate change has favoured some types of extreme event right across the globe.

And the message for policymakers is “striking”, says Prof Peter Stott, who leads the Met Office’s climate attribution team but who wasn’t involved in the study.

Extreme weather

Global temperature today is about 0.85C above what it was before the industrial revolution, and most of the rise is driven by human activity. But rising greenhouse gases mean more than an increase in global average temperature. It means changes in extreme weather, too.

Prof Reto Knutti from the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich and co-author of the new study, tells Carbon Brief:

“Warmer temperatures overall create more hot days, and warmer air can hold and transport more moisture, which at some point must come down. These physical principles have been known for decades.”

A number of scientific studies have linked increases in extreme temperatures and heavy rainfall to a warming climate.

But what has been lacking up to now is an estimate of the fraction of extreme events occurring worldwide that are attributable to human activity, says Stott in a summary article accompanying the new paper.

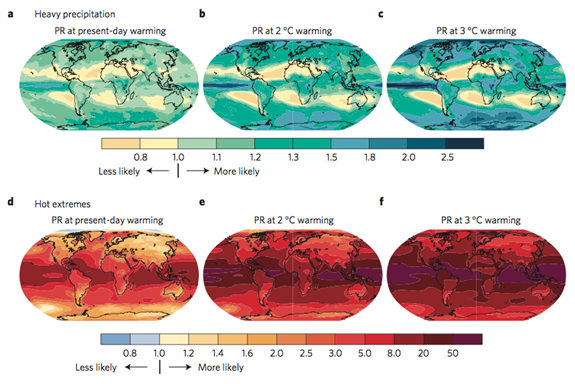

Using a number of climate models, the new study compares the chances of daily temperature or rainfall extremes crossing a given high threshold in today’s climate, compared to a pre-industrial world. The difference between the two probabilities is the contribution of climate change, the paper explains.

Flooding in SAMUTPRAKARN, THAILAND in 2008. Source: Shutterstock.

Upping the odds

The results suggest that 75% of daily temperature extremes that we experience across the world today are attributable to climate change. Similarly, 18% of days with rainfall above a certain level wouldn’t have occurred on a planet that wasn’t warming.

In other words, the probability of an event crossing the threshold into “extreme” territory is a lot higher now than it was in preindustrial times. Knutti tells Carbon Brief:

“If a day with temperature exceeding a certain threshold used to occur once in three years, and now occurs once every year because of human-induced warming then human influence has tripled the probability of such an event occurring, and two out of three events are attributable to human influence.”

This doesn’t mean some individual extreme events are caused exclusively by climate change and some aren’t. It’s about changing odds, Knutti explains:

“It’s the same as smoking increasing the risk of dying from lung cancer. One might be lucky and be fine, and it’s hard to determine the exact cause of death. But it’s clear that smoking increases the risk of dying from cancer, and some fraction of those death can, therefore, be attributed to that cause.”

Two degrees and beyond

The team extended their study to look at how extreme weather with 2C of warming – the internationally-accepted limit to avoid dangerous climate change – differs from today.

At 2C above pre-industrial temperature, the probability of an extreme hot day is almost double the probability at 1.5C, and is more than five times higher than with today’s climate.

The paper notes:

“This result has strong implications for the discussion of different mitigation targets in climate negotiations, where differences between targets are small in terms of global temperature, but large in terms of the probability of extremes.”

At 2C warming, events expected once every 30 years now will begin happening every 10 to 20 years instead, the paper notes.

Averaged across the globe, almost all extreme daily temperatures and around 40% of heavy rainfall events will be attributable to climate change with 2C of warming. Stott says:

“The idea that in a 2C world almost half of heavy rainfall events would not have occurred were it not for climate change is a sobering thought for policymakers seeking to mitigate and adapt to climate change.”

Change in the probability of heavy precipitation (top) and hot extremes (bottom) with present day warming, with 2C and 3C warming. All relative to preindustrial temperatures. Source: Fischer et al., ( 2015)

A fast moving field

The science of connecting changes in weather and climate to their causes is known as attribution. Up till now, scientists have used it to say how climate change has made a particular event more or less likely, usually quite soon after it has subsided.

For example, scientists at the University of Oxford found that heavy and prolonged rainfall episodes, such as the one the UK experienced in the winter of 2013/4, are now 25% more likely because of climate change. Similarly, recent research shows the likelihood of a very hot summer has risen from once every 50 years to once every five years.

Since these studies look at the changing likelihood of individual events, they are known as single-event attribution studies.

While they are useful for communication and for understanding local adaptation needs, they don’t tell you much about changing risk in other parts of the world. The paper says:

“[Studies] for the 2003 European heatwave are only valid for the observed anomaly over the specific area, but do not apply to a similar event occurring further east.”

The new research gives a bigger picture view of what’s happening, Knutti tells Carbon Brief:

“The global view is relevant for a large country, for example, to estimate the risks of extreme weather overall, no matter where it happens, or for reinsurance, agriculture and food security, where the aggregated damages matter.”

Loss and damage

Just knowing how frequently an event is likely to occur isn’t enough to assess risk on its own, says Knutti. What are important are the impacts on the ground. He adds:

“The damage depends on how much infrastructure is there, on building standards, protection measures, on warning systems, disaster response, etc., so the same weather event can lead to much more or much less damage depending on what or who is there, and how those people are prepared and respond to that threat.”

Understanding and comparing risk across the world means combining information about extreme weather with maps of exposure and vulnerability. The paper says:

“For instance, the fraction of heavy precipitation and hot extremes attributable to warming is highest over the tropics and many island states, which typically have high vulnerability and low adaptive capacity.”

Prof Myles Allen, a climate scientist from the University of Oxford and author of a number of attribution studies, tells Carbon Brief the new study is “a great effort” towards documenting how climate change has affected extreme weather risk. But what’s needed next, he says, is for it to be translated into a better understanding of climate damages. He says:

“I think we need to go one stage further and model the contribution of anthropogenic climate change to the actual impacts of extreme weather, and then compile a global inventory of harm, not just of meteorological events, if we are to arrive at an objective assessment of loss and damage due to anthropogenic climate change.”

While the authors acknowledge that there’s more to be done in terms of separating out any influence on extreme weather trends from other factors like solar activity, the new study seems to go a long way towards achieving that goal.

Main image: Skull in the desert.

Anthropogenic contribution to global occurrence of heavy-precipitation and high-temperature extremes. Nature Climate Change. DOI: 10.1038/NCLIMATE2617

-

Human activity responsible for three out of four heat extremes, study finds