Mat Hope

20.10.2014 | 4:55pmWhat happens when a major gas power station catches on fire? Well, it certainly looks spectacular. But it appears the short term impact on the UK’s power generation is pretty minimal.

Energy company RWE npower had to unexpectedly shut down one of the Didcot B power station’s 700 megawatt units last night after a fire broke out in one of the cooling towers.

Didcot’s shutdown is the latest in a series of unexpected outages which National Grid has had to cope with in recent months. This has led to a spate of headlines questioning whether National Grid will have enough power stations available to cope with high demand over the winter months.

We take a look at how National Grid copes with such unexpected events, and why it remains confident the UK will have enough power this winter.

Where does the UK’s power come from?

National Grid is legally required to make sure there’s always enough power to meet demand. The UK’s peak demand – at around 6pm on weekdays – is currently around 45 gigawatts. This is expected to rise to about 55 gigawatts over the winter, as people spend more time indoors and use more electricity.

Big coal, gas, and nuclear power stations are responsible for meeting most of this demand. The government’s latest statistics show 30 per cent of the UK’s electricity comes from gas, with 28 per cent coming from coal. Nuclear power provides about 20 per cent.

When one of these power stations has to be taken offline, it’s big news. Earlier this year, the Heysham 1 and Hartlepool nuclear reactors with a total capacity of 2.3 gigawatts shut down after engineers discovered cracks in their boiler casings. Both power stations are due to come back online before Christmas, although they will only be operating at 70 to 80 per cent of their normal output, the Telegraph reports.

Two coal power plants – at Ferrybridge and Ironbridge – also caught fire over the summer, meaning National Grid has had to do without their combined 1.4 gigawatts of capacity in recent months.

Coping with outages

National Grid says that each time there has been an outage, it has managed to cover the electricity production shortfall without much difficulty.

How? Mainly by increasing production from other power stations.

The graph below graph shows the amount of power the UK’s gas power stations provided over the last 24 hours (the orange line) compared to overall demand (the blue line).

Because demand is pretty low on Sunday evenings (the blue line), National Grid didn’t struggle to find spare power from other sources when Didcot B was shut down. As you can see, National Grid was already ramping down gas power output (the orange line) when Didcot B closed, and the outage made very little difference to output at the time:

The real challenge came this morning, when everyone got out of bed and made a cup of tea – and demand spiked.

So what filled the gap?

Last week’s electricity demand was fairly similar to this week’s. Using this time last week as a reference point, we can roughly estimate how much coal, gas, nuclear and renewables National Grid would have expected to call on this morning if Didcot B hadn’t closed.

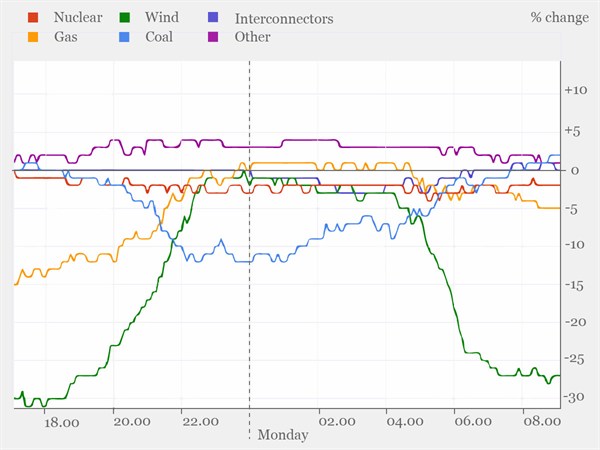

If Didcot B’s outage had a major affect on the UK’s gas power supply, you’d expect to see gas providing much less of the UK’s demand this morning than on Monday morning last week. The graph below shows that wasn’t really the case.

The graph shows the percentage change in the proportion of demand each energy source accounted for last night and this morning, compared to the same time a week ago:

It shows National Grid was able to call on other fossil fuelled power plants to fill the gap left by Didcot B’s shutdown. The fact that most of the energy sources only provided a couple of per cent more or less power to the grid this morning shows the impact of Didcot B closing was very short term.

The main thing driving National Grid’s technology choices seems today is the fact there was less wind available this morning than the same time last week, rather than Didcot B’s outage.

When Didcot B was shut yesterday, National Grid called on a whole range of energy sources to make up the difference.

Within a couple of hours, gas generation had been ramped up to the extent that it was providing for about the same share of the UK’s electricity demand as last week. National Grid also called on companies to ramp up coal power generation, as you can see from the rising light blue line.

The UK also imported slightly more electricity (the dark blue line), and National Grid used some stored power to balance the grid (the purple line).

National Grid has spare capacity to draw on because many of the UK’s fossil fuelled power plants aren’t running at full capacity – gas plants are generally producing only about a third of the electricity they could provide.

Coal plants are currently only producing about two-thirds of the electricity they could. So when there’s a big outage, as there was yesterday, it’s relatively straightforward for National Grid to ask companies to increase the amount of electricity those power stations are producing.

One reason coal and gas plants are running at less than full-power is that the UK has been building lots of renewables. That allows energy companies to rely on renewable power, save money on fuel, and leave some power spare for when National Grid needs it.

It has also implement a scheme called the supplemental balancing reserve to make sure there’s always power available at a second’s notice.

Yesterday’s experience shows National Grid has enough spare capacity at its disposal to cope with unexpected outages fairly comfortably – when demand is fairly low, at least.

‘Blackouts’

What about this winter, when demand increases? We’ll find out the grid’s answer to that question next week, when National Grid releases its Winter Outlook report, outlining its plans for the coming months.

Traditionally, the report’s launch has been met with media speculation about the ‘lights going out’. But while that’s a useful shorthand for journalists and politicians discussing the UK’s energy needs, widespread power cuts remain very unlikely.

Market regulator Ofgem recently said it expects National Grid to only have enough spare power to cover a five per cent spike in demand, or three gigawatts of unexpected outages.

That would be enough to cover an outage the size of yesterday evening’s four times over. Latest reports suggest Didcot B may be fully back online before demand gets really high, anyway.

The government recently announced plans to decrease the risk of outages even further, through a capacity market that will ensure the UK should have more than enough spare power to cover peak demand in 2017/18.

Yesterday’s fire means National Grid may need to adjust its plans to cover demand this winter. But with the amount of spare capacity in the system, blackouts remain a distant possibility – unless something truly extraordinary happens.