Ros Donald

20.05.2014 | 1:30pmHow much climate change can humans stand? That’s the question policymakers should be asking themselves as they contemplate ways to adapt to climate change, according to an Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) expert.

Professor Frans Berkhout was speaking at Exeter University’s Transformational Climate Science. He coauthored a chapter for the IPCC entitled ‘Adaptation, Opportunities, Constraints and Limits‘, which examined just how far it is possible to adapt to climate change.

The authors used a risk-based analysis to consider how we might adapt, or fail to adapt, to effects of climate change like sea level rise, crop depletion and extreme heat. Berkhout tells Carbon Brief:

“We drew on a small literature that exists and tried to develop a risk-based framework for thinking about limits [to adaptation]. The Working Group 2 report regional and sectoral chapters did for the most part engage with this new concept, but the idea of limits is not very visible in the [report’s] Summary for Policymakers and Technical Summary. I think this is because some of the ideas are still quite fresh.”

The barriers to adapting to climate change are likely to be significant, yet understanding of such limits is underdeveloped, Berkhout told delegates last week.

Most mathematical models examining how humans can adapt to climate change assume there’s no point at which it won’t be possible – even under warming of up to 10 degrees above pre-industrial levels, he said. Berkhout warned that this could lull policymakers into believing that humans can continue to adapt to the effects of climate change indefinitely.

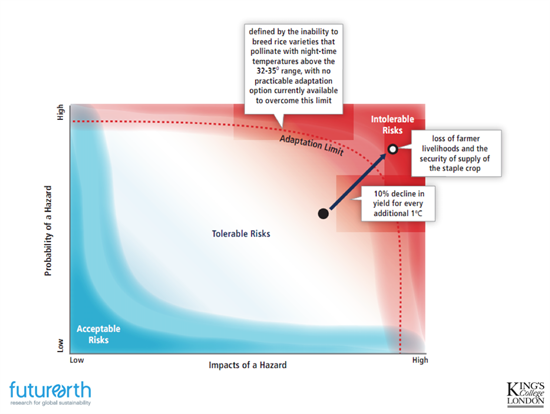

Humans should be able to adapt to some changes – but Berkhout suggests that it will never be possible to adapt to all of the losses associated with climate change. At some stage, as climate impacts increase, these losses will be judged as intolerable. That definition of what will be intolerable is key for policymakers attempting to judge the level of risk they are able to accept, he said.

The IPCC has been very keen to emphasise the idea that addressing climate change is an exercise in risk management. Ultimately mitigation – or limiting the amount of climate change the world gets – will be necessary to manage risks, it emphasises.

Limits to adaptation in practice

So what do limits to adaptation look like in practice?

In 2011, temperatures in Thailand got so high that rice yields started to dip. Above a nighttime threshold temperature of 26 degrees Celsius during rice pollination, yields started to decline by 10 per cent for every extra degree of warming. Above 32 to 35 degrees, the rice varieties available in Thailand don’t pollinate at all.

The graph below, contained in Berkhout’s slides, illustrates a model for understanding what the ingredients of this situation mean.

The “adaptation limit” is defined as the threshold above which rice will no longer pollinate. Up to the threshold, there are a range of impacts that policymakers can try to manage.

There’s lots of research to do in this area in the future, Berkhout said. And policymakers must start to ask themselves hard questions: If they can no longer grow rice in the near future, would they be willing to switch to wheat? If global policymakers don’t pursue more stringent mitigation policies, what are the costs of accepting a higher level of risk?

Berkhout pointed out that risks aren’t just confined to one area – the climate system is interconnected. Policymakers must take account of how cascading risks can influence the limits to adaptation.

Despite the reflection Berkhout’s chapter demands of policymakers, its failure to make it into the parts of the report aimed at those who make the decisions raises questions about how much attention it will get. Berkhout tells Carbon Brief:

“The IPCC reports have tended to be more successful at communicating the facts and impacts of climate change, rather than in handling adaptation. [The most recent report] devotes more space to adaptation. [But] whether that will lead to greater awareness is an open question.”

You can read more on the risk-based analysis of adaptation limits here.