Robert McSweeney

20.08.2014 | 3:14pmWhen you’re chipping ice from your car windscreen or sheltering from the snow on a windswept platform, you might find yourself wondering how climate change fits in with the flurry of cold winters we’ve seen in recent years.

One theory suggests very cold winters in the northern hemisphere could be linked to rapidly increasing temperatures much further north – in the Arctic. A new paper outlines three ways scientists think the two could be linked.

Rapid Arctic warming

Temperatures in the Arctic have been increasing almost twice as fast as the global average. This is known as Arctic amplification. As Arctic sea-ice shrinks, energy from the sun that would have been reflected away is instead absorbed by the ocean.

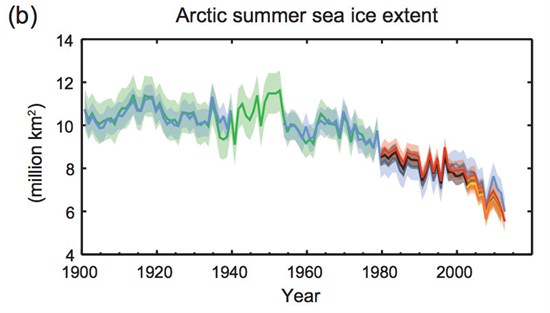

From 2007 to 2013, we’ve seen some of the lowest summer sea ice levels since records began, as shown in the graph below. This has coincided with a number of extreme cold and wet events across the mid-latitudes of the northern hemisphere, including the cold start to 2013 in the UK and the record low temperatures in the US and Canada during the 2013-14 winter.

Arctic sea ice summer extent has decreased by between 9.4 to 13.6% per decade. Source: IPCC 5th Assessment Report, Summary for Policymakers

Some scientists have suggested this extreme weather is a result of Arctic amplification. A new paper in published in Nature Geoscience runs through three potential explanations of what could be happening.

Storm tracks

The wintry weather we’re used to in the UK is largely caused by storms coming in from the mid-Atlantic. The passage these storms take are known as ‘storm tracks’.

When the storm tracks fall directly over the UK, we get wet and mild conditions. When the storm tracks pass to the south, colder air is drawn in from northern Europe and Russia, making winters much colder.

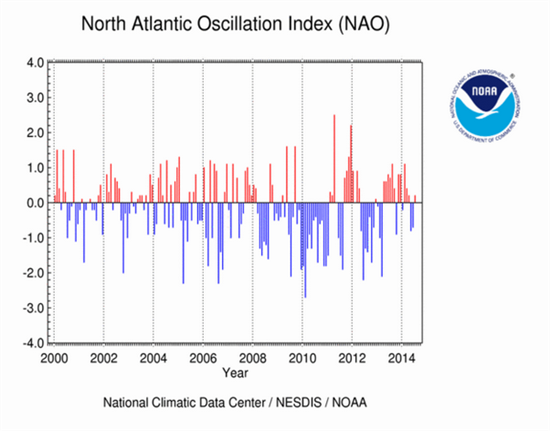

The position of storm tracks is affected by a natural fluctuation known as the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO). When the NAO is positive, the storm tracks fall over the UK; when negative, they fall to the south. So a negative NAO is associated with colder winters – like the ones we’ve seen recently.

The NAO has been largely negative since the turn of the century and some scientists suggest it is being affected by recent changes in sea ice. The authors say in the paper:

“Observational analyses have shown significant correlation between reduced Arctic sea-ice cover and the negative phase of the winter NAO.”

But they also say that the NAO is naturally highly variable, and so the impact of reduced sea-ice is only small in comparison. This suggests that variations in the NAO are still predominantly driven by its natural fluctuations.

The NAO has been mainly negative since the turn of the century, as shown by the blue lines on the graph above. Source: NOAA

Jet stream

Scientists also think Arctic amplification could be affecting the jet stream – a band of fast-flowing air high up in the atmosphere.

The jet stream received a lot of media attention in recent UK winters as a possible cause of prolonged cold weather. It’s driven by the temperature difference between the Arctic and the mid-latitudes.

The theory goes that as the Arctic warms, this temperature difference decreases. This means the jet stream weakens, causing it to meander more and allow cold air to pulled eastwards over the UK.

While some initial observations support the theory, there is not currently enough evidence to be convincing. This leads the authors to say that:

“[C]hallenges remain in linking Arctic amplification directly to changes in the speed and structure of the jet stream.”

Rossby waves

The third explanation involves ‘Rossby waves’ – which consist of large air masses at high-altitude. Rossby waves move north and south and create meanders in the jet stream. These waves can slow down or ‘block’, at which point the weather experienced on the ground will remain for some time. This could be a prolonged period of cold or rain, or a heatwave in the summer.

Reductions in sea-ice extent in the Arctic have been linked to high pressure systems over the Arctic that push cold air towards northern Europe and brings cold weather to the UK. So these high pressure air masses may have a role in locking weather conditions in. But the paper highlights that modelling studies have not been able to simulate these wave changes particularly well.

This is an active area of research. Another recent paper, published this week in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, the impact of Arctic amplification on Rossby waves is linked to a range of extreme weather events in northern hemisphere summers, such as Europe’s heatwave in 2003.

Knowledge gaps

With three potential links between Arctic amplification and extreme mid-latitude weather, there is still a long way to go before any relationship is fully understood.

There is relatively little data around the poles and Arctic amplification has only been detected in the last two decades.

However, the paper stresses that the question is “a critical one” as scientists predict Arctic amplification will continue into the coming decades.

The paper also serves as a reminder that increasing global temperatures doesn’t preclude periods of very cold weather. Indeed, the paper concludes that:

“Cold winters such as the one experienced in 2013-2014 have occurred before and are expected as part of normal weather variability even on a warmer planet.”