Contracts for renewable electricity signed by the Department of Energy and Climate Change (DECC) in May were poor value for taxpayers, according to an influential committee of MPs.

The contracts, worth up to £16.6 billion over their lifetime, were awarded in May to eight projects including five offshore windfarms and three plants that will burn wood to generate power. The National Audit Office published a report on the deals in June that made very similar complaints to the MPs.

So why are the contracts being criticised?

Regime change

The government is introducing a new subsidy scheme for low carbon energy starting in April 2015, called contracts for difference (CfDs). DECC decided to sign early CfDs with these eight large projects because it was worried there would otherwise be a gap in investment as we change over from the previous subsidy regime.

It’s these early contracts that the NAO and MPs on the Public Accounts Committee are unhappy about. Both are unconvinced that an investment hiatus would really have materialised.

They would have preferred the contracts to be handed to the lowest bidder in a competitive auction. They say this would have guaranteed the best possible value for consumers, who will ultimately foot the bill.

DECC largely agrees with this in principle. It will award future contracts on a competitive basis and announced this week that auctions for contracts worth £300 million will be held this autumn.

But for these early deals it set the price for the CfDs without any detailed information about how much the projects would actually cost to build. The MPs fear this leaves the door open to developers making windfall profits if they can build at lower cost than DECC expects. And they add that it will be impossible to claw back any windfall, because of poor drafting of the contracts.

The MPs say DECC was “too ready” to accept arguments put forward by project developers and failed to “robustly challenge” their assertions on how the contracts should be drafted. Developers successfully persuaded DECC that investment would not forward unless they were protected from inflation and claw-back clauses. But the MPs could find “no evidence to substantiate” these concerns.

Margaret Hodge MP says:

“Yet again the consumer has been left to pick up the bill for poorly conceived and managed contractsâ?¦ [DECC] should have learnt the lessons from PFI.”

PFI is the private finance initiative, introduced in 1992 as a way to get the private sector to invest in public schemes such as new hospitals and schools. It has been widely criticised – including by the chancellor George Osborne – for being poor value for the taxpayer.

Unfortunately there’s no way to tell in advance if the early CfDs criticised by the MPs and the NAO are really poor value or not, because the projects have not actually been built yet. The committee of MPs say DECC should robustly evaluate the actual costs and benefits once this happens. It should also publish the results.

So we won’t know if it was a dud deal for a while, even assuming DECC publishes an evaluation at some point. For now, energy and climate secretary Ed Davey is standing by the move.

In a statement Davey says:

“To keep the lights on in British homes and businesses we needed to move quickly to secure new capacity and give investors confidence – fast. These contracts are better for billpayers in the long run because it means that we’re able to move to real competition for contracts much faster.”

Ignoring the bigger picture

A wider concern identified by the MPs is whether or not the renewable power projects were actually necessary. The projects will have a capacity of 4.5 gigawatts when completed, helping the UK hit its 2020 target to get 15 per cent of its energy from renewable sources.

But the MPs point to DECC data showing there is already a lot of renewable generation capacity in the pipeline. As a result, the eight contracts DECC has signed may not have been needed, they argue.

Similar arguments have been around for a while now. They have found favour with those that are opposed to renewable energy in general, and onshore windfarms in particular.

The biggest problem with these arguments is that renewables are only one part of the government’s strategy towards meeting the 2020 target.

The aim is to get 15 per cent of all energy from renewable sources, not just 15 per cent of electricity. Progress in other areas, such as insulating homes or driving uptake of electric cars is behind schedule. That means more renewable electricity capacity might be needed than the government first projected.

What’s more, UK efforts to decarbonise will not stop with the 2020 target. The UK’s legally binding Climate Change Act that requires an 80% cut in carbon emissions by 2050. This law could be scrapped. For now, though, it is still supported by all the major political parties.

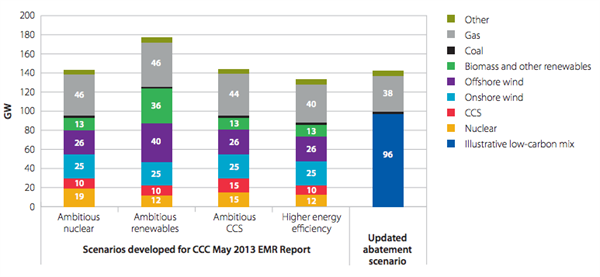

There a a number of ways to reach the binding 80% carbon reduction. All of them involve a substantial increase in renewable electricity capacity beyond 2020, according to the government’s Committee on Climate Change.

Source: CCC projections

Its projections involve at least 64 gigawatts of renewable electricity capacity in 2030 (see chart). That’s nearly double the figure expected in 2020 and four times current capacity. It’s also a minimum that assumes ambitions on nuclear power, carbon capture and storage or energy efficiency are ramped up significantly.

So unless future governments plan to breach their own laws they had better hope renewable developers keep on building.