Guest post: Will China’s new renewable energy plan lead to an early emissions peak?

Hu Min

07.07.22

Hu Min

07.07.2022 | 12:48pmChina released its 14th five-year plan (FYP) for renewable energy on 1 June, outlining the country’s renewable energy roadmap for the five years 2021-2025.

This is the first sub-sector plan issued since the 14FYP for a modern energy system, published earlier this year. Among all the documents that China has issued under the so-called “1+N” policy framework for enforcing its climate pledges, the energy plan and its sub-sector plan on renewable energy might be the most fundamental to China’s decarbonisation.

China’s climate pledge (its “nationally determined contribution”, or NDC) aimed for 1,200 gigawatts (GW) of wind and solar power capacity by 2030, and for 25% of energy consumption to be met by non-fossil fuels by 2030. Achieving these goals is expected to ensure China’s carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions peak before 2030, but to fall short of a pathway towards carbon neutrality.

Therefore, to the extent that the new 14FYP for renewables can meet or overperform on its goals, it would also contribute to China’s effort to peak carbon emissions early and help bridge the global emission reduction gap towards a 1.5C pathway.

What is in the renewable energy plan?

The 14th FYP for renewable energy sticks with the previously announced vision of 25% of China’s energy coming from non-fossil sources by 2030. In order to increase the share from 15.9% in 2020 to 20% by 2025, the plan lays out a framework with a series of targets and actions.

Specifically, these cover: renewable energy production in million tonnes of coal equivalent (Mtce), overall and for non-electricity supplies; renewable electricity generation in terawatt hours (TWh); and renewable energy share in the grid (%), overall and for non-hydro sources. The details for each of the targets are shown in the table below.

| End of 2020 Actual | 2025 target in 14FYP | 2030 NDC target | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-fossil fuel share of total energy consumption | 15.9% | 20% | 25% |

| Renewable energy output | 680Mtce | 1,000Mtce | Wind and solar capacity 1,200GW |

| Renewable energy (excluding electricity) | 60Mtce | 60Mtce | |

| Renewable electricity | 2,210TWh | 3,300TWh | |

| Renewable electricity share | 28.8% | 33% | |

| Non-hydro renewable electricity share | 11.4% | 18% |

Unlike renewable development plans over the past decade, the new version abandons the mandatory generation capacity increase targets, which were the focus of the previous two renewable FYPs.

For example, the 13th FYP for renewable energy aimed for renewable power capacity, in total, to reach 680GW by 2020 – and for wind to reach 210GW.

But, in some respects, the new plan increases ambition. For example, it requires “newly increased renewable generation [to] make up more than 50% of the incremental electricity consumption” – in other words, that at least half of the increase in demand be covered by renewables.

Based on estimated growth in demand and the planned expansion of nuclear and hydropower, our analysis suggests that this target means generation from wind and solar would need to increase by around 150TWh annually over the 14th FYP period from 2021-2025.

This can be compared with the 100TWh annual average increase from wind and solar seen during the 13th FYP period – and the 255TWh increase recorded during 2021.

Will China overperform its renewable targets?

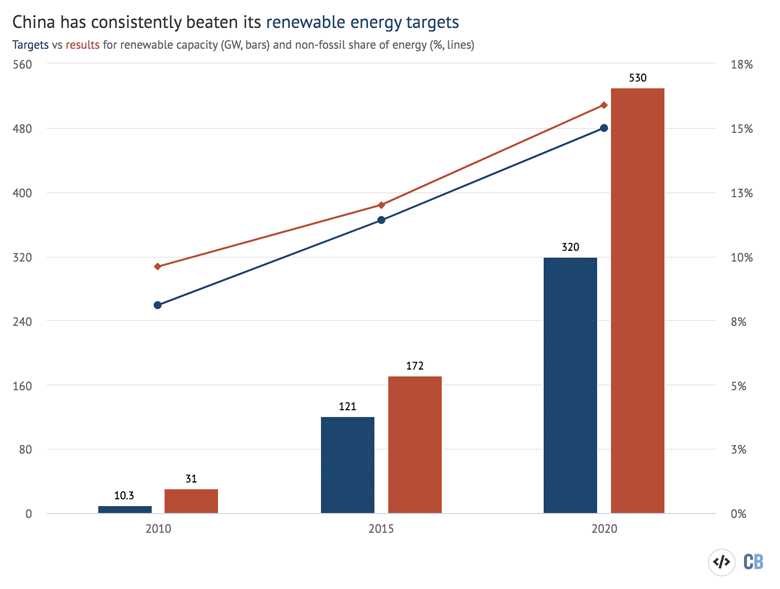

China has a track record of overperforming on renewable energy development goals in the last three FYPs. Since China first included a renewable goal in its energy plan, in the 11th FYP period, most of the quantitative goals for development of the sector have seen overperformance, especially wind and solar total capacity growth targets.

This is shown in the figure below, where the wind and solar capacity targets from the 11th (2006-2010), 12th (2011-2015) and 13th FYPs (2016-2020) are shown as blue bars and China’s actual capacity growth is shown in red. The figure also shows the FYP targets for the share of total energy consumption from fossil fuels (grey line, right-hand axis) against the actual share in red.

The new renewable plan targets total renewable energy output of at least 1,000Mtce by 2025 – up from 680Mtce in 2020 – which means an annual increase of at least 64Mtce is needed.

To generate that much energy, based on the current energy mix, at least 100GW of wind and solar capacity needs to be added annually in the next five years. This is more than the annual increase of more than 75GW from 2021 to 2030 needed to reach China’s NDC goal of 1,200GW of wind and solar by 2030 – meaning the renewable plan is likely to lead to overperformance.

Ambitious implementation at the local level could also contribute to overperformance at the national level. Reviewing the 14th FYPs for energy development issued by each province, 23 out of 34 regions and areas have set wind and solar capacity growth targets, amounting to more than 120GW per year between 2021 to 2025.

(Analysis published by Carbon Brief in May found at least 570GW of capacity set to be built during the 14FYP period, while recent press reports suggest more than 150GW could be built this year.)

The economic impact of renewable investments

China is experiencing an economic slowdown that has seen carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions fall for three quarters in a row, a trend expected to deepen as a result of strict Covid lockdowns.

China’s cabinet, the State Council, issued a package of measures to stabilise economic performance. Premier Li Keqiang has emphasised that “China’s economy is facing greater challenges than [in] 2020”.

Nevertheless, China’s development of renewable energy is expected to continue soaring.

In the same week as the economic stabilisation package, the Ministry of Finance released what Reuters described as “fiscal and taxation policies to support the shift towards carbon neutrality”, with support for the implementation of the 14th FYP for a modern energy system as the primary action.

Renewable energy investment has been an important economic engine in China and will play an even more significant role in boosting the economy than before, at a time when China faces the economic impact of Covid and uncertainties caused by the Ukraine crisis.

In 2021, China’s investment in clean energy took up more than 30% of the total global investment, according to the International Energy Agency, and this trend will continue.

Implications for the global energy transition

Cheap renewables offer an answer to climate change, the energy crisis and inequality. China’s renewable investments will contribute to rising energy output from the sector, as well as offering the potential to boost domestic and global economic growth, by driving down wind and solar cost and by creating economic opportunities in terms of manufacturing and deployment.

Having dominated the solar panel market, China’s companies are now leading the global markets for electric vehicles (EVs) and batteries. Chinese companies CATL and BYD are responsible for producing the batteries for 39% of the world’s EV fleet.

The Global Wind Energy Council’s 2022 report indicates that China recently surpassed the UK and Germany in offshore wind, becoming the largest offshore wind market in the world, accounting for 40% of the global total installed capacity.

According to the new 14th FYP for renewables, China has committed to building offshore power “bases” in five regions. Six coastal provinces’ energy development plans indicate a total of 32GW offshore wind capacity growth during the 14th FYP period 2021-2025, which would represent an increase of more than 60% on the 2020 level.

China’s ambitious development plan means a growing market for all offshore turbine manufacturers, of which the western companies are still leading the market share.

Challenges of decarbonising the energy mix

The success of the renewable energy plan will rely heavily on building large-scale renewable energy bases and creating market mechanisms leveraging renewable energy integration to the grid.

Meanwhile, the growing penetration of wind and solar in China’s electricity mix will require flexible resources that can balance and accommodate fluctuations in renewable output. These resources include energy storage, demand-side management and flexible operation of fossil fuel plants.

Prioritising clean and inexpensive ways to balance renewable energy, in support of China’s climate goals, rather than the conventional fossil fuel approach that has been used in the past, will only be possible with smart policy design and appropriately designed pricing signals.

The renewable energy 14FYP includes measures promoting pumped hydro and other energy storage approaches. The National Energy Administration has also announced that permits for new coal power plants would be issued only if the projects are supplementary to renewables.

Despite all these efforts, however, there is still a risk that China’s growing coal capacity could run counter to the country’s efforts to decarbonise its energy mix.

-

Guest post: Will China’s new renewable energy plan lead to an early emissions peak?