Guest post: Why action on extreme heat in Indian cities is falling short

Multiple Authors

03.19.25Local governments face the difficult task of preparing communities and infrastructure for a warmer world – all while urbanisation accelerates and extreme weather becomes more frequent and intense.

But officials responsible for implementing heat resilience actions face significant challenges, in large part because many of the required solutions take time to implement.

For example, trees planted to provide shade require several years to mature before their benefits are felt.

For India specifically, inadequate long-term heat preparedness could have serious consequences.

Heatwaves are already harming public health and economic productivity in the south-Asian nation and are expected to increase in frequency and duration with global warming.

In a new report, we analyse how prepared India is for the heat extremes projected under 1.5C of warming by assessing the implementation of long-term heat risk-reduction measures in nine cities.

To understand how heat resilience measures were being implemented in these cities, we interviewed 88 government officials working in a range of departments – including health, disaster management, labour, planning and horticulture.

The research finds that solutions being implemented are generally short term and weakly targeted – posing a major threat to the ability of communities to adapt to the future climate.

India’s growing urban population

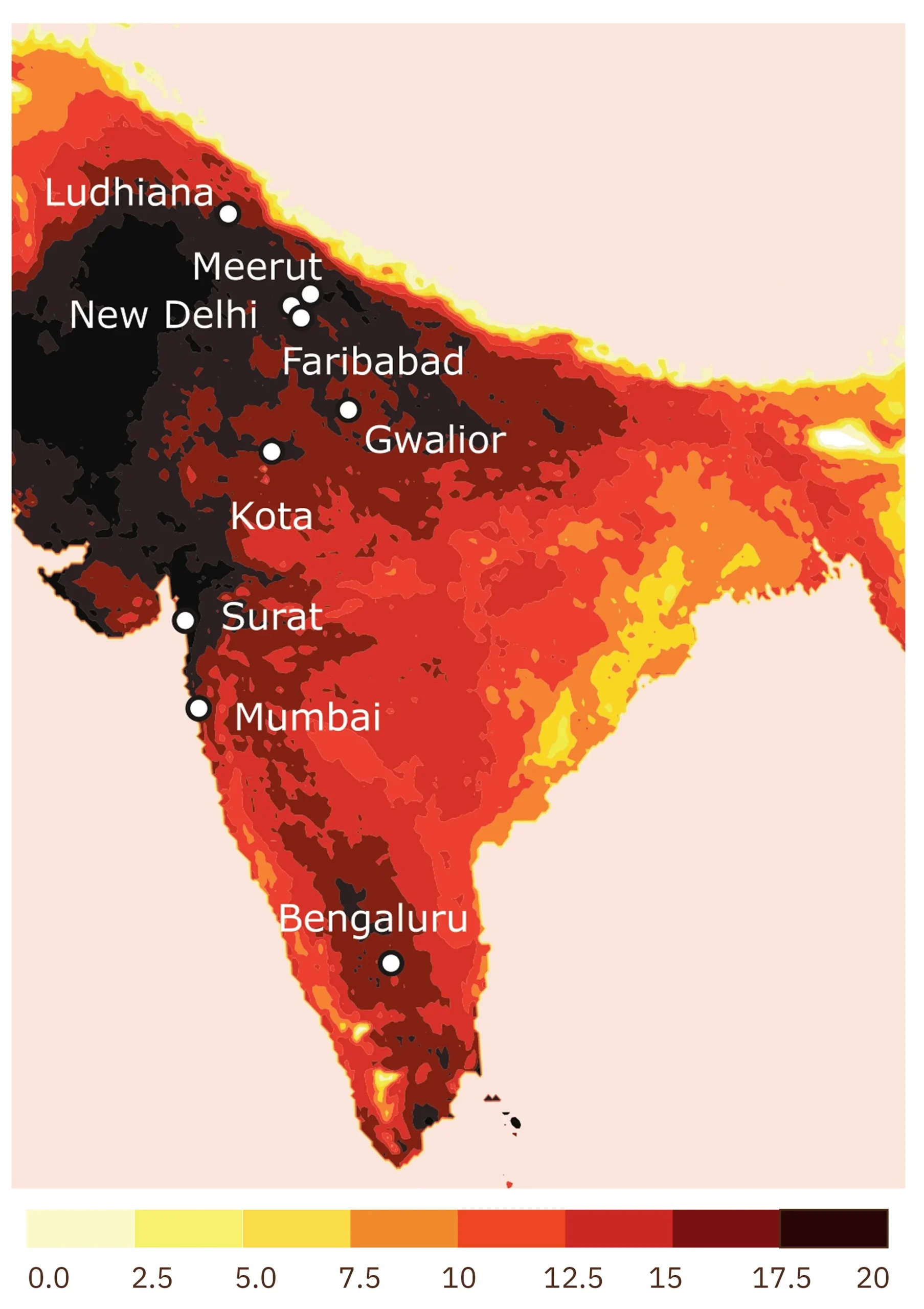

The cities covered by our study – Bengaluru, Faridabad, Gwalior, Kota, Ludhiana, Meerut, Mumbai, New Delhi, and Surat – represent a diversity of institutional and economic contexts. Some cities are large and others are growing, while each belongs to a different state.

Together, they are home to 11% of the nation’s urban population and provide a proxy for India’s overall preparedness for heat extremes under 1.5C of global warming.

We selected these nine cities because they are expected to see some of the largest increases in dangerous heat under 1.5C of warming compared to a 2013-22 baseline, according to projections in the CMIP6 ensemble of climate models.

Specifically, these cities are projected to experience the largest increase in days where temperatures exceed the 98th percentile of the local heat index, a measure which combines temperature and relative humidity to provide an understanding of how hot it feels outside. Heat index values exceeding the 98th historical percentile are typically associated with significant increases in mortality and morbidity.

We use this measure, rather than just the largest number of extreme heat days, because communities and institutions that experience significant climate change are less likely to be equipped to cope than those that have historically faced extreme heat.

The map below shows the location of the nine cities and the projected increase in frequency of exceeding the 98th percentile of the heat index under 1.5C of global warming. The darker shading indicates those areas seeing the largest increases.

A lack of long-term actions

Our research finds that cities in our sample have already begun grappling with extreme heat.

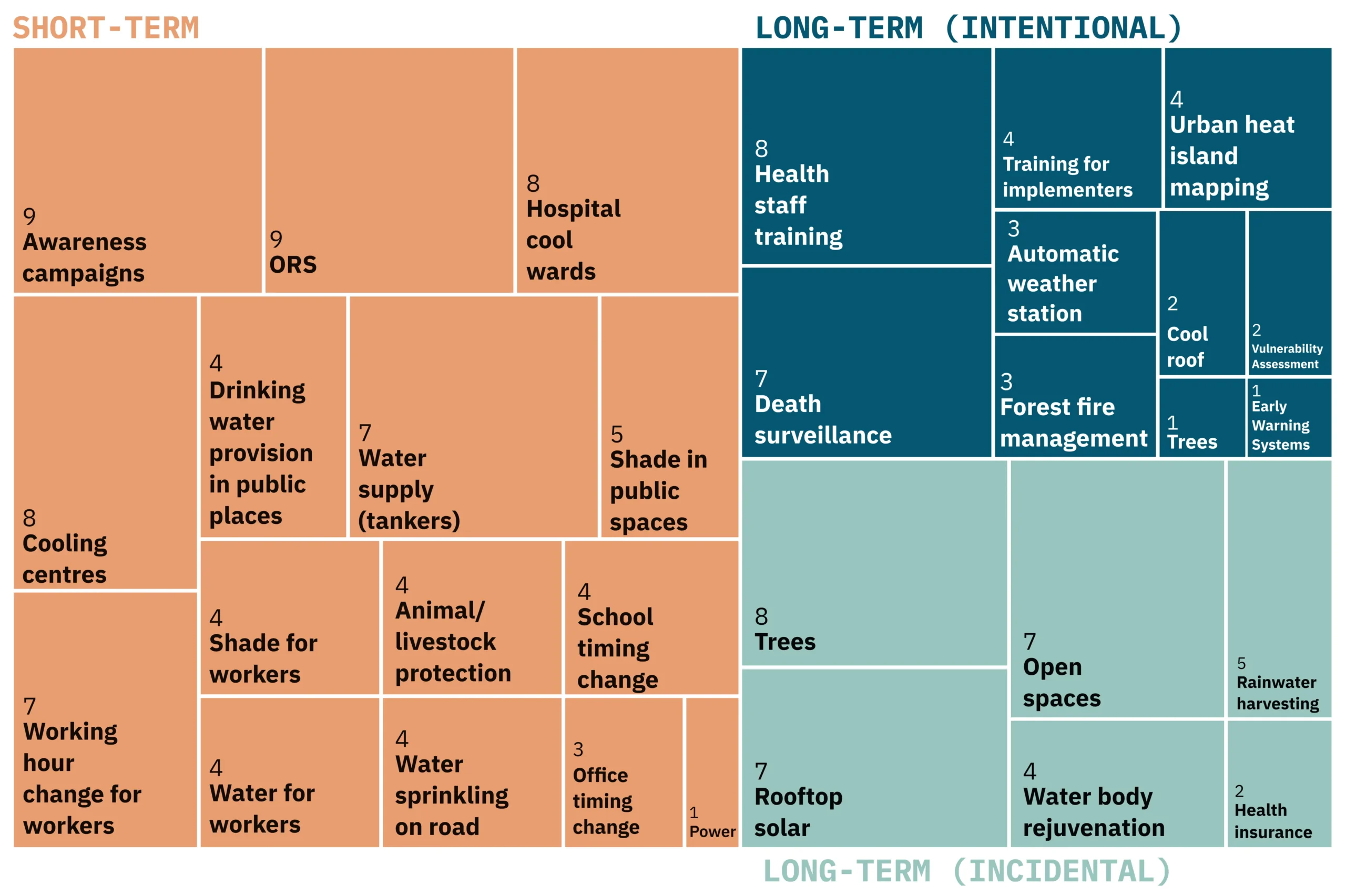

Officials from all nine cities reported taking emergency actions to deal with immediate health consequences. This includes actions such as awareness campaigns, repurposing hospital wards for the treatment of heatstroke patients and changing work times.

However, the study finds that cities are much less likely to implement long-term actions that can be implemented now to reduce future heat risk in these cities, such as large-scale tree planting.

Meanwhile, health system preparedness actions make up a significant proportion of long-term measures specifically being introduced to increase heat resilience – initiatives grouped in the study as “long-term heat intentional actions”.

These actions – which include health staff training and death surveillance measures – are of foundational importance to heat resilience, as they deal with the consequences of heat overwhelming the adaptive capacity of societies.

However, long-term heat intentional actions that sit outside the health system – which are typically designed to prevent society’s adaptive capacity from being overwhelmed in the first place – were less common in cities studied. A picture of very weak mainstreaming of long-term heat actions emerges when health system preparedness is excluded from the analysis.

The study also finds that many actions with potential long-term benefits – which includes the expansion of urban shade and green cover, the creation of open spaces that dissipate heat and the deployment of rooftop solar that can power building cooling systems – were being implemented as a part of routine developmental policy, with few direct links to heat concerns.

These actions – which are grouped in the study as “long-term heat incidental actions” – are not specifically targeted at the most heat-vulnerable areas of the cities studied. As a result, they could have weak and inconsistent effects on heat resilience.

The execution of these long-term incidental actions undoubtedly contributes to adaptive capacity for dealing with heat. However, the fact they are not explicitly designed to also address extreme heat is a missed opportunity.

In eight of the nine cities, for example, trees planted were not aligned with heat vulnerability assessments. Officials in multiple cities reported challenges to planting trees in dense, hot slums and informal settlements, where land is scarce and politically fraught.

Meanwhile, some key long-term measures are entirely missing, including: insurance for lost working hours lost, which is crucial as heat chips away at productivity; electricity grid retrofits that can meet the rising electricity demand from cooling; and cooling access for the most vulnerable.

The figure below shows cities’ skew towards short-term heat actions. The boxes illustrate the range of reported short, long-intentional and long-incidental heat solutions implemented in the nine cities, with the size of each box indicating the number of cities that reported implementing each solution.

Barriers to heat policy

The distribution of inconsistent and weakly targeted long-term heat actions in our sample suggests that India will likely see more frequent heatwaves with higher mortality levels in the coming years.

In other words, the lack of these actions could see communities’ adaptive capacities overwhelmed by rising temperatures.

When looking into the reasons why cities are falling short, many of our findings are consistent with barriers to adaptation and heat governance reported in other countries.

Officials reported limited public pressure for long-term heat resilience. The focus – from both the public and elected politicians – was on short-term measures to alleviate the immediate suffering wrought by heat, including preventing drinking water shortages and shifting work hours.

A notable exception was high levels of support for more trees. However, in some cases, popular pressure pushed in the wrong direction, with challenges to access to public land and groundwater undermining the provision of heat solutions.

These weak and conflicting signals are compounded by scant financial and legal backing for heat-related policy. India’s heat plans have proliferated rapidly at multiple levels of government, but are generally neither backed by law or finance, giving them little purchase in already-stretched local governments.

Sixteen of the 25 respondents in our study who discussed weak heat governance reported not seeing their jurisdiction’s heat plan, which meant they would be unlikely to implement their sectors’ resilience actions this year.

(For more detailed analysis of the gaps in heat action plans in India, see an earlier Carbon Brief guest post.)

Instead, the study finds that actions – particularly emergency health measures put in place just before and during a heatwave – are largely driven by directives from higher levels of government. Moreover, these directives from national and state disaster management and health authorities – rather than local heat planning efforts – are less likely to capture local context and challenges.

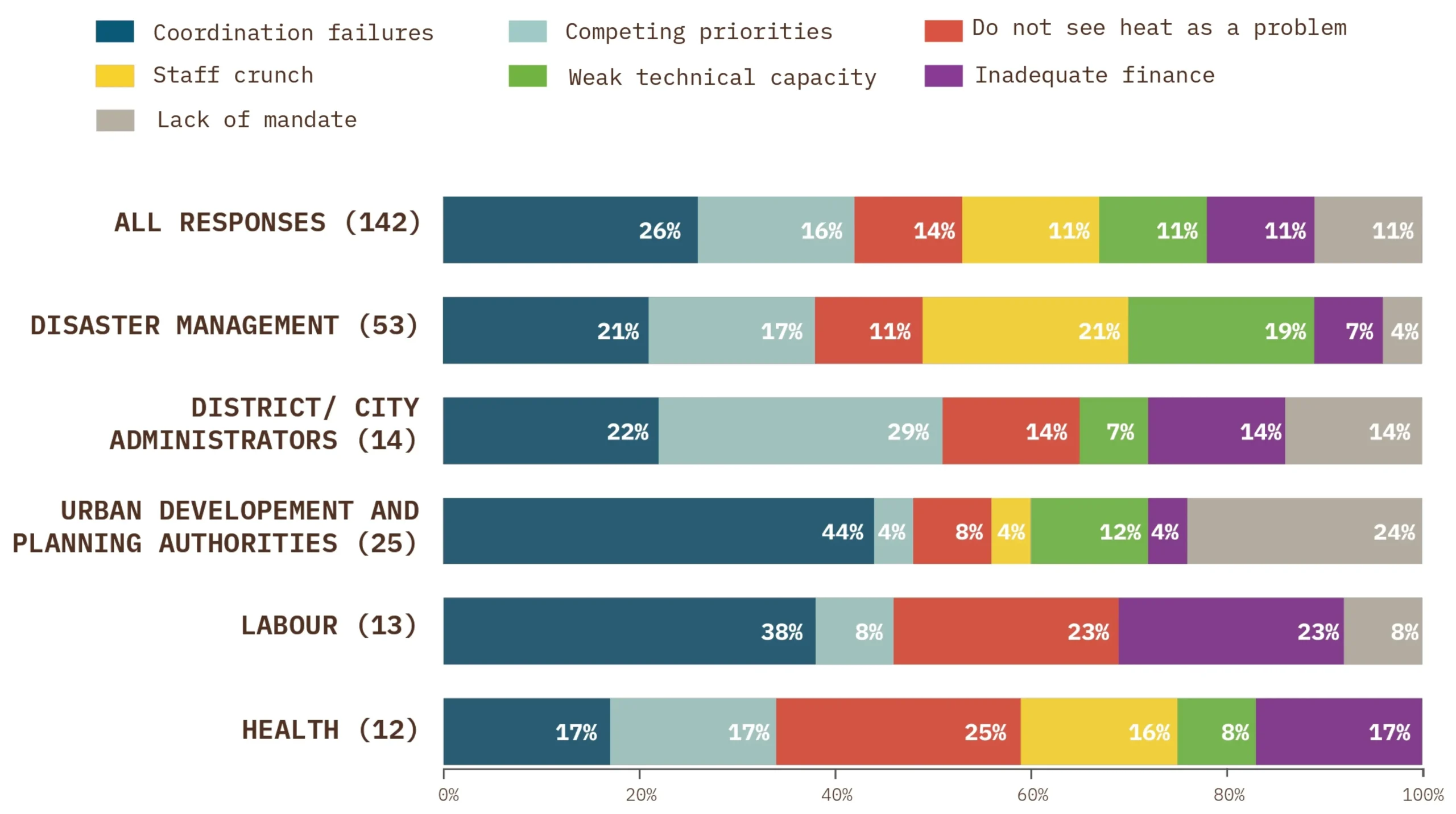

Our research shows that limitations in the structure of the state – from faltering coordination between departments, to competing priorities in short-staffed bureaucracies with weak technical capacity – limit the prospects of long-term planning.

The figure below shows a breakdown of institutional barriers holding back heat actions in the nine cities studied, as reported by government officials.

It demonstrates that – across all government departments – coordination problems (dark blue bars) are seen as the single largest constraint on implementation, followed by competing priorities (light blue) and the view that heat is not a policy problem (red).

Practical solutions

Practical measures could help tackle a number of the barriers to building heat resilience in Indian cities.

Embedding long-term resilience for extreme heat and other climate hazards in legal structures, alongside appropriate financial backing, could improve accountability and the monitoring of solutions. This could involve updating climate and disaster management legislation to make implementation of extreme heat actions mandatory.

Meanwhile, many of the most commonly reported problems set out in the figure above could be tackled with sustained capacity building in local government. This could include a combination of new positions dedicated to extreme heat and staff training on appropriate resilience measures.

Adequately staffed, financed and trained local government officials are more likely to coordinate with each other, deal with simultaneous and competing priorities and understand the urgency of implementing long-term actions.

In addition, making crucial climate information available to government officials tasked with designing and implementing heat measures could result in a more targeted response.

This could include regional climate model output that provides projections on what the most dangerous days of heat will look like in the hottest parts of cities – and vulnerability assessments and urban heat island maps showing spatial variation in impacts.

While our research focuses on India, many of the challenges it highlights are likely to be similar in other rapidly developing global south countries.

Adapting to increasing extreme heat will be central to urban living for decades to come. A late start to these efforts will increase pressure on the state in the future and risks exposing citizens to harms from warming that could be avoided.

Our peer-reviewed report is published by the Sustainable Futures Collaborative, an independent research organisation analysing issues in climate change, energy and the environment. A version of the paper is due to be published in an academic journal later this year.