Guest post: Is China living up to its pledges on climate change and energy transition?

Dr Xie Chunping

02.21.22

Dr Xie Chunping

21.02.2022 | 2:32pmIn September 2020, China pledged to become carbon neutral by 2060 and this climate target was officially submitted in an updated nationally determined contribution (NDC) to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) last October.

More than a year has now passed since China’s initial announcement. What expectations of progress does the world have of China – and has China lived up to them?

To explore these questions, my colleagues and I have examined China’s domestic and foreign policymaking – with a focus on the energy transition, sustainable finance and innovation – in a new policy paper.

We found that China has made great strides in implementing its climate obligations domestically, but will not meet its goals without urgent additional action to drive a clean energy transition at home and abroad.

Energy transition

Globally, the energy sector accounts for 73% of the human-caused greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. Therefore, promoting the transition of energy away from fossil fuels to reduce energy-related carbon emissions is at the heart of the climate change challenge. As the world’s largest current emitter, China’s energy transition attracts particularly close scrutiny.

Domestically, China’s carbon neutrality pledge has set a direction for the country’s evolving energy policy, with the “1+N” policy framework unveiling detailed pathways for the country to become carbon neutral before 2060.

It also put forward targets for the short-term, such as a 13.5% reduction in energy consumption per unit of GDP – also known as energy intensity – and an 18% reduction in carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions per unit of GDP – also known as carbon intensity – during the 2021-25 period.

A recent report by the International Energy Agency (IEA) suggests if these short-term targets for 2025 are achieved, China could peak its carbon emissions at around 2025 and then enter a modest decline between 2025 and 2030.

However, as China is expected to maintain a lower but still-strong pace of growth, a declining energy intensity or carbon intensity is not guaranteed to reduce its overall carbon emissions.

Based on the International Monetary Fund (IMF) projection of China’s future growth, capping CO2 emissions at 10.6bn tonnes by 2025 – compared to 9.9bn tonnes in 2020 – would allow China to achieve the carbon intensity target. But with faster rates of economic growth, the country’s CO2 emissions could reach even higher levels, even while meeting its carbon intensity target.

The lack of an absolute cap on China’s carbon emissions is, therefore, a key gap in its climate targets, creating significant uncertainty at home and internationally. Such a target would be a more straightforward marker for the carbon neutrality effort and could provide a clear signal on earlier emissions peaking.

Dual control

China’s sustained growth of energy demand as the economy expands, as well as its emission control policies implemented for meeting the energy and climate goals, have led to concerns about the country’s ability to ensure the security of energy supply.

In the fourth quarter of 2021, boosted by a strong economic recovery, surging demand and interruptions to coal supply led to electricity supply shortages in many regions of China. Industrial power users were further affected by power rationing implemented by some provinces in order to meet the country’s “dual-control” targets that limits total energy consumption and energy intensity. To ease the growing supply crunch, China took a series of measures to boost coal production capacity and revise electricity prices.

These domestic measures have global significance because China currently consumes more than half the world’s coal and is continuing to build more coal-fired power plants to meet its growing energy demand.

Its current energy policy framework has been emphasising “dual-control”, with a cap on total energy consumption rather than on fossil fuel energy consumption. The latter could directly promote the development of renewables and reduce the risk of stranded fossil fuel assets in the future.

(A recent study examined the stranded asset risks from existing and planned coal-fired power plants in the world. It estimated that, under a 1.5C policy, immediate action on not building new coal-fired plants can potentially avoid a $520bn, or £382bn, increase in stranded assets globally.)

Renewable energy

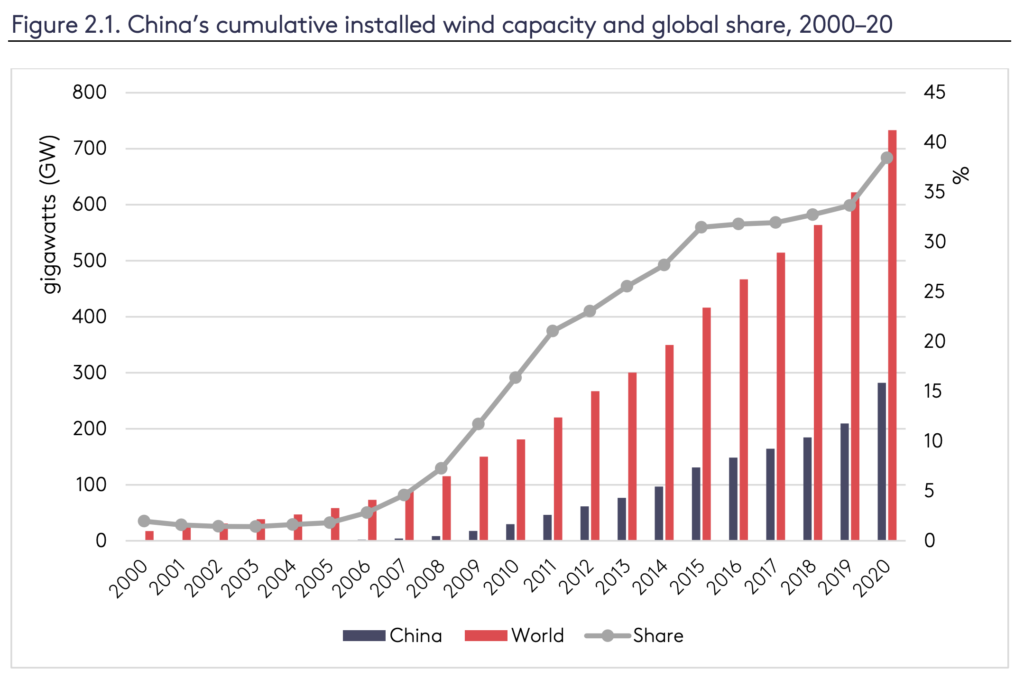

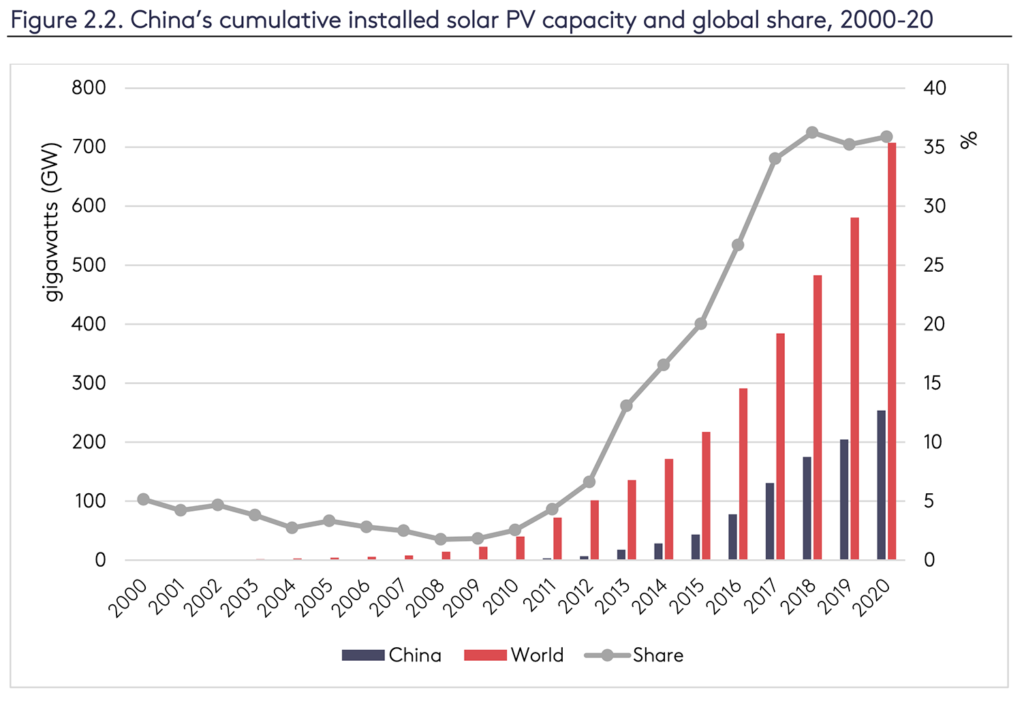

China is now leading the world in renewable development, with its cumulative installed wind capacity and solar capacity taking up a global share of 39% and 36%, respectively. And its current plan is to increase the share of non-fossil energy in total energy consumption to 25% by 2030 and more than 80% by 2060.

The illustrations below show how China’s cumulative installed capacity of wind power (top) and solar power (bottom) compare to the global totals between 2000 and 2020, respectively.

Considering that fossil fuels still made up 88% of China’s total primary energy supply in 2020, the country will not meet its non-fossil energy target without continuing to rapidly increase renewable generation capacity and significantly improving the integration of renewables into the grid.

The variability of wind and solar highlights the increasing need for flexibility in the power system to balance real-time mismatches between electricity demand and supply in order to ensure grid stability. A recent paper explored various policy options to improve grid flexibility and argued that power market reform is the key to unlocking the flexibility potential of these measures.

In a market-based economic dispatch, renewable generators would have priority due to their near-zero marginal costs. A newly released policy document shows China’s determination to deepen its power market reform.

For now, however, the electricity price formation mechanism in China remains heavily distorted under its unique dual-track system (双轨制), which sets two prices for the same commodity – one state-controlled and one market-based.

Similarly, electricity transmission and distribution prices have continued to be administratively lowered by the government. The regulated prices cannot reflect real-time cost of electricity generation and the generation unit with the lowest costs is not prioritised for meeting electricity demand.

Besides power market reform, China’s carbon emission trading scheme (ETS) officially started in July 2021 and has the potential to drive energy sector transition.

In its current incarnation, however, it is not expected to contribute significantly to switching away from coal power generation, due to its unique design and resulting low carbon prices of approximately 40-60 yuan (£5-7) per tonne of CO2 in 2021.

A report by the IEA estimated that under a scenario where the carbon price rises from 100 yuan (£12) per tonne of CO2 in 2020 to 360 yuan (£42) per tonne of CO2 by 2035, China’s power sector could generate 12% less CO2 in 2035, compared to the no-carbon-pricing scenario.

This suggests that even though the current carbon prices are very low, the ETS could play an important role in the low-carbon transition in China if more ambitious carbon pricing policies are introduced.

International role

China’s engagement in the climate agenda is often viewed through a domestic policy lens. However, there is increasing interest in China’s role in international collaboration and coordination in climate action, as my colleague and I discuss in our new paper.

In terms of the global energy transition, we found that China could play a key role, not only as the world’s largest emitter of CO2, but also as the front-runner in clean-energy technologies and an increasingly important lender to developing countries.

In particular, our research shows that China could share the experience with – and learn from – other countries to further increase the integration of renewables into the grid, which is identified as one of the key areas for cooperation under the US-China Joint Glasgow Declaration.

Our paper suggests that China could remain as the primary global supplier of low-carbon equipment – notably in the solar, wind and battery storage industries – by continuing to increase research and development efforts in these areas.

It could also lead the world’s nuclear power development, including expanding domestic nuclear power fleet and deploying “third-generation” nuclear power generation capabilities through investment in countries under its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), where appropriate and cost-effective.

China has announced that it “will not build new coal-fired power projects abroad”, which could be a significant step in catalysing international climate actions.

As set out in more detail in our recent paper, there is potential for China to play a bigger role in global climate governance. For example, it could actively foster green commercial investment through the BRI and other means, including by addressing barriers to investment in host countries and helping create fiscal space for promoting sustainable development in poorer countries through international collaboration on debt.

-

Guest post: Is China living up to its pledges on climate change and energy transition?