Guest post: How Ukraine could emerge from war as a climate leader

Multiple Authors

08.08.23The ongoing, devastating war with Russia has pushed Ukraine to the edge of survival as a nation-state, inflicting severe damage to its economy and population.

As the war grinds on, damage grows day by day, while the cost of recovery is already estimated at $411bn.

But, amid global calls for urgent climate action, Ukraine now finds itself at a crucial crossroads.

When the country emerges from the war, it will have a rare chance to reshape the economic foundations of the nation, shifting it towards lower-carbon sectors and enhancing economic prosperity, energy security and environmental protection for generations to come.

In a new working paper from the University of Oxford’s Smith School of Enterprise and the Environment, we analyse Ukraine’s 10-year national plan for economic recovery through a climate lens – and detail a plan for lower-carbon “green” recovery.

Pre-war Ukraine

Ukraine’s economy has historically been carbon-intensive, with carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions per unit of GDP (carbon intensity) far exceeding the world average.

Beyond this, it has struggled to reach its full economic potential for many decades, remaining categorised as a lower middle-income country in the same economic group as countries including Nigeria, Ghana and Pakistan.

Structural weaknesses in the Ukrainian economy have included a high dependence on fossil fuel imports, monopolisation in key industries (including fossil fuel-heavy energy), significant skewing to export of raw goods rather than value-added products and persistently low investment in modernisation (including in low-carbon technologies).

Each of these deficiencies could be overcome by reorienting the economy towards “green” emerging and established sectors, our paper suggests.

Mid-war Ukraine

The ongoing war has inflicted severe damage to Ukraine’s economy and population. Over six million Ukrainians have fled the country, people are losing their lives in combat, and those who remain at home are often without work and losing their skills. Recovery planning will, therefore, also need to consider new and pressing demands on human capital.

With regards to financial capital, GDP dropped 29.1% in 2022, with taxation revenue crashing in tandem. The costs of rebuilding are already estimated at $411bn, or more, and the damage grows day by day.

Exports of steel and grain, the nation’s most influential commodity products, were hindered by blockades and shelling to transport and other infrastructure, causing enormous losses for metallurgical and agricultural businesses.

The physical losses of the conflict are also enormous. Intentional damage to electricity assets has impacted more than 40% of the country’s power grid, bringing rolling blackouts, even through the winter.

As one example, the demolition of the 10 gigawatt (GW) Kakhovka hydroelectric power station in June, triggered mass flooding and the destruction of a major reservoir, which was used for cooling the largest nuclear plant in Europe. The flooding affected around 10,000 hectares of agricultural land and caused environmental damages worth approximately $1.5bn. The restoration of the Kakhovka dam itself would take an estimated five years and require about $2bn in investment.

Analysis of current recovery plans

The Ukrainian government released the first version of its 10-year national recovery plan at a head-of-states conference in Lugano, Switzerland in July 2022. The plan proposed recovery pathways for major sectors, at a projected cost of $750bn.

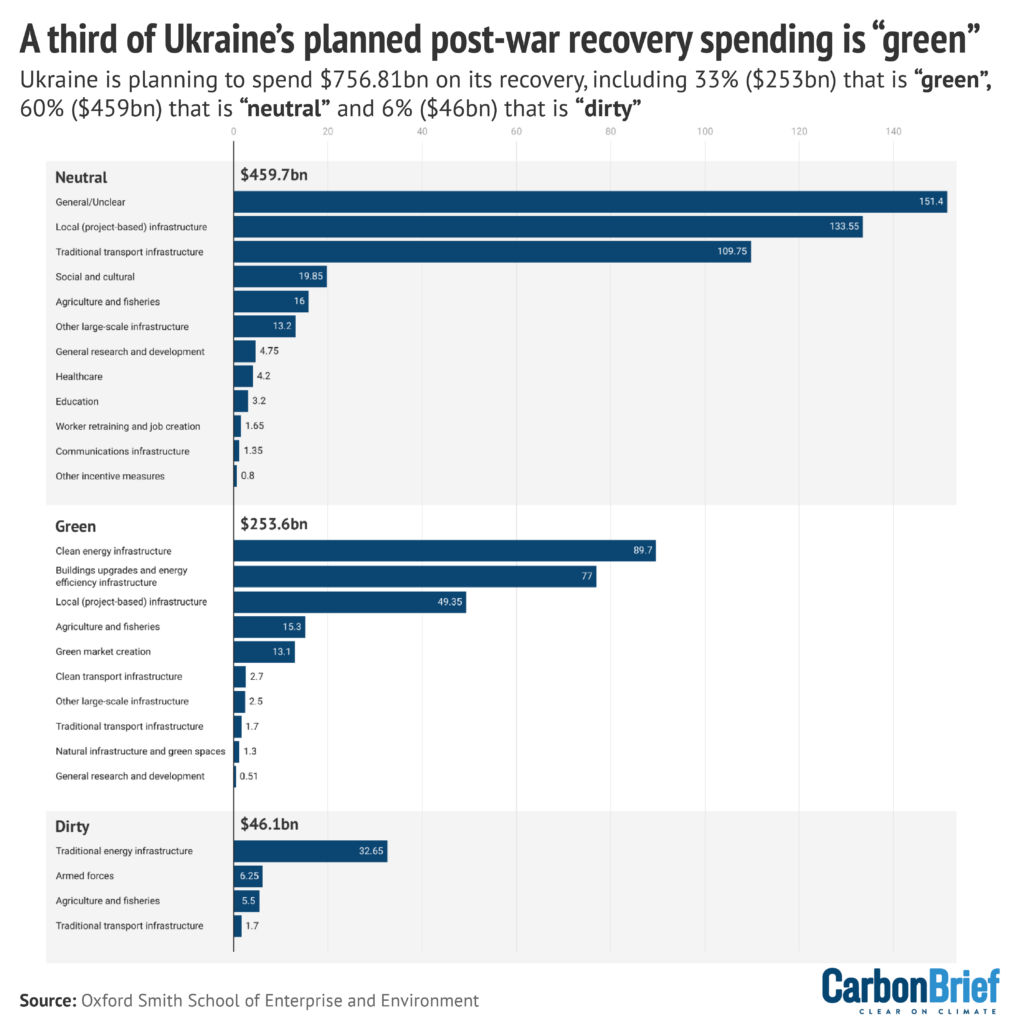

For our new paper, we applied the “green recovery taxonomy” of the Global Recovery Observatory to this spending, finding that $253bn (33%) of proposed spending could be considered “climate-positive” and, therefore, likely to increase progress on climate change mitigation.

However, we classified the remaining 67% as being unlikely to advance climate objectives. Of this, $46bn is considered likely to directly contradict mitigation efforts – mostly due to oil and gas exploration and new fossil fuel infrastructure.

Our research shows that this increased fossil fuel investment would worsen health outcomes, hinder the transition to a lower-carbon economy, increase Ukraine’s carbon intensity and increase climate impacts by contributing to further warming.

Increasing fossil fuel investment would also expose Ukraine to higher stranded asset risks, meaning the nation’s fossil infrastructure could be subject to premature write-downs, devaluations or conversion to liabilities due to the climate transition. This could bring economic losses, uncontrolled job losses, stagnation of industry and loss of communities, we found.

To put the 33% climate-positive figure in context, in response to the recent Covid-19 crisis, EU nations directed an average of 42% of recovery spending to climate-positive initiatives, according to the report and shown in the figure below. Poland’s climate-positive recovery spending approached 75%.

But there are increasing signs of green-recovery ambition from Kyiv.

On 30 June 2023, the Ukrainian parliament adopted new legislation to encourage investment in renewable energy and modernisation of the energy system. With increased renewable energy, Ukraine can replace damaged fossil energy assets, reduce its reliance on energy imports and improve sustainability, all acting to increase economic prosperity.

In July 2023, Ukraine reaffirmed its commitment to phasing out state-owned coal power plants by 2035 and announced a new additional proposal for a $40bn programme to develop a coal-free steel industry, as a first step towards a “Green Marshall Plan”.

Some 40% of Ukraine’s metallurgical assets were destroyed in the Russian siege and occupation of Mariupol. This presents an opportunity to re-establish a new, decarbonised industry to meet domestic steel demand for rebuilding. International support is already forming behind this effort.

Where to from here?

Our own recent interactions with Ukrainian policymakers suggest that a green recovery is increasingly a shared vision. According to our research, welfare and growth can be decoupled from greenhouse gas emissions, meaning that a green recovery and a welfare-maximising recovery are conceivably the same thing.

However, considerable planning is required to optimise this sweet spot. Aligning the interests of business, government and international finance requires a well-defined and credible plan, which will take time to develop.

We provide recommendations to accelerate recovery planning:

- Replace “dirty” policies: we consider that proposed Ukrainian spending on fossil fuel industries is unlikely to return high dividends for the public and introduces large economic and environmental risks. Our research suggests that these could be diminished by directing spending to greener options.

For instance, instead of developing new gas fields to increase energy access and high-value exports, we propose scaling low-carbon energy production and decarbonising domestic industrial processes.

Instead of expanding gas transmission networks, we propose repurposing and optimising gas infrastructure so it might be used to transport and store renewably-produced energy. (For example, biomethane or CO2 for carbon capture, utilisation and storage.)

- Improve “neutral” policies: in many cases, proposed spending that has little perceived impact on climate objectives could be made greener through only minor changes, our research found.

For instance, support for conventional agriculture could be greened by prioritising spending for advanced irrigation practices and alternative proteins.

Funds to (re)construct roads and bridges could include priorities for dedicated bus lanes, cyclist-friendly design, electric vehicle charging infrastructure and use of low-carbon materials for construction.

- Fill gaps with green solutions: existing recovery plans miss various structural gaps important to a green economic transformation in Ukraine, we found.

For instance, there is a need for new infrastructure to be resilient to a changing climate. Nature-based solutions and other adaptation-friendly solutions could also be used in support.

Additionally, if Ukraine is to pursue a low-carbon economy, it could benefit from becoming a technological leader in sectors such as hydrogen production or “green” steelmaking. Large-scale investment in research and development could attract talent home and catalyse Ukrainian climate leadership.

Training and reskilling are likely to be core components to any Ukrainian recovery plan. If a low-carbon shift is desired, much of these investments in human capital would need to prioritise skills relevant to the low-carbon economy, such as solar panel installation or retrofitting a house.

From the ashes of war, Ukraine has the chance to rise as a green phoenix, a global climate leader through green recovery – building not just a resilient economy, but a sustainable future for its people and the world.

Zagoruichyk, A, et al. (2023) The Green Phoenix Framework: Climate-Positive Plan for Economic Recovery in Ukraine, ISSN 2732-4214