Guest post: How to apportion ‘net-zero carbon debt’ if global warming overshoots 1.5C

Multiple Authors

04.09.25As global warming approaches the Paris Agreement’s 1.5C limit, the likelihood of at least a temporary temperature “overshoot” looms into view.

This puts global climate action into a new context, where the focus is not only on rapid reductions of greenhouse gas emissions, but the large-scale removal of atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2) in order to bring global temperatures back down below 1.5C.

However, in a world where the carbon “budget” for 1.5C is already used up, which countries and regions should lead the collective effort to bring temperatures down?

In a study, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), we propose a new forward-looking measure for calculating regional and national responsibility for climate overshoot.

This measure – “net-zero carbon debt” – takes into account a region’s historical CO2 emissions, its projected future CO2 emissions and its “fair share” of the remaining carbon budget for 1.5C of warming.

Our findings show that some regions, such as western Europe and North America, will accrue net-zero carbon debt as soon as 2030.

Meanwhile, other regions, such as sub-Saharan Africa and southern Asia, are likely to become debtors only if they fail to achieve net-zero CO2 emissions this century.

Our research also illustrates the adverse implications of net-zero carbon debt for younger generations in debtor regions – from increased exposure to heatwaves to greater responsibility to cut CO2 emissions and rapidly scale carbon removal technologies.

Our results highlight the importance of policies that both minimise global temperature overshoot and consider a region’s historical contribution to climate change.

Defining responsibility

The year 2024 was the first in which the annual average global temperature at the Earth’s surface exceeded 1.5C above pre-industrial levels.

While reaching 1.5C in an individual year is not equivalent to a breach of the Paris Agreement’s 1.5C limit – which refers to long-term warming – it nevertheless indicates that the world is rapidly approaching the threshold.

This raises questions around how to fairly and collectively manage the harms of a likely overshoot beyond 1.5C.

(Overshoot refers to a period where warming exceeds 1.5C until temperatures are brought back below the limit by removing CO2 from the atmosphere.)

In our research, we look at which regions are the most responsible for overshoot of the temperature threshold.

We do this by proposing a measure for calculating a region’s “net-zero carbon debt”, which considers three factors:

- A region’s historical CO2 emissions, using data provided by the Global Carbon Budget project hosted at the University of Exeter’s Global Systems Institute.

- A region’s projected CO2 emissions under a range of scenarios assessed in the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s (IPCC’s) 2022 Working Group III (WG3) report. We use scenarios where regions achieve net-zero CO2 by 2090 at the latest.

- A region’s “fair share” of the remaining carbon budget for staying below 1.5C. We illustrate “fair share” using equal per-capita emissions allocations of the total carbon budget from the year 1990. However, recognising that there are various ways to approach this often-charged concept, we also explore a number of approaches.

We define net-zero carbon debt as any emissions generated by a region that exceed its “fair share” at the point it reaches net-zero CO2 emissions.

The concept of carbon debt is not new. Previous studies have defined it in terms of excess emissions once historical emissions are taken into account.

Our work extends the concept to consider past and projected emissions under different pathways to reaching net-zero CO2, including scenarios where the 1.5C limit is temporarily exceeded.

The purpose of the net-zero carbon debt measure is straightforward. It tracks which regions will bear responsibility for tackling climate overshoot in a way that explicitly accounts for past cumulative emissions. It can be applied both today and when the carbon budget for 1.5C is exhausted.

The measure can help assess whether domestic and international mitigation efforts are on track or falling short, while illustrating the importance of near-term reductions to carbon emissions that can reduce a region’s future carbon debt.

Regional patterns

Our research reveals distinct regional patterns to net-zero carbon debt.

Some regions consistently accrue debt across all scenarios, whereas others accumulate debt depending on when the countries within them collectively achieve net-zero targets.

The paper identifies two groups of debtors:

- Earlier debtors – regions with high historical emissions, which typically accrue carbon debt by 2030 regardless of scenario, such as North America and western Europe.

- Later debtors – regions with rising future emissions, which typically accrue carbon debt after 2030, such as a regional block covering Latin America and the Caribbean. This includes a subgroup of regions which may not accumulate carbon debt until after 2100 under announced pledges, such as sub-Saharan Africa or southern Asia.

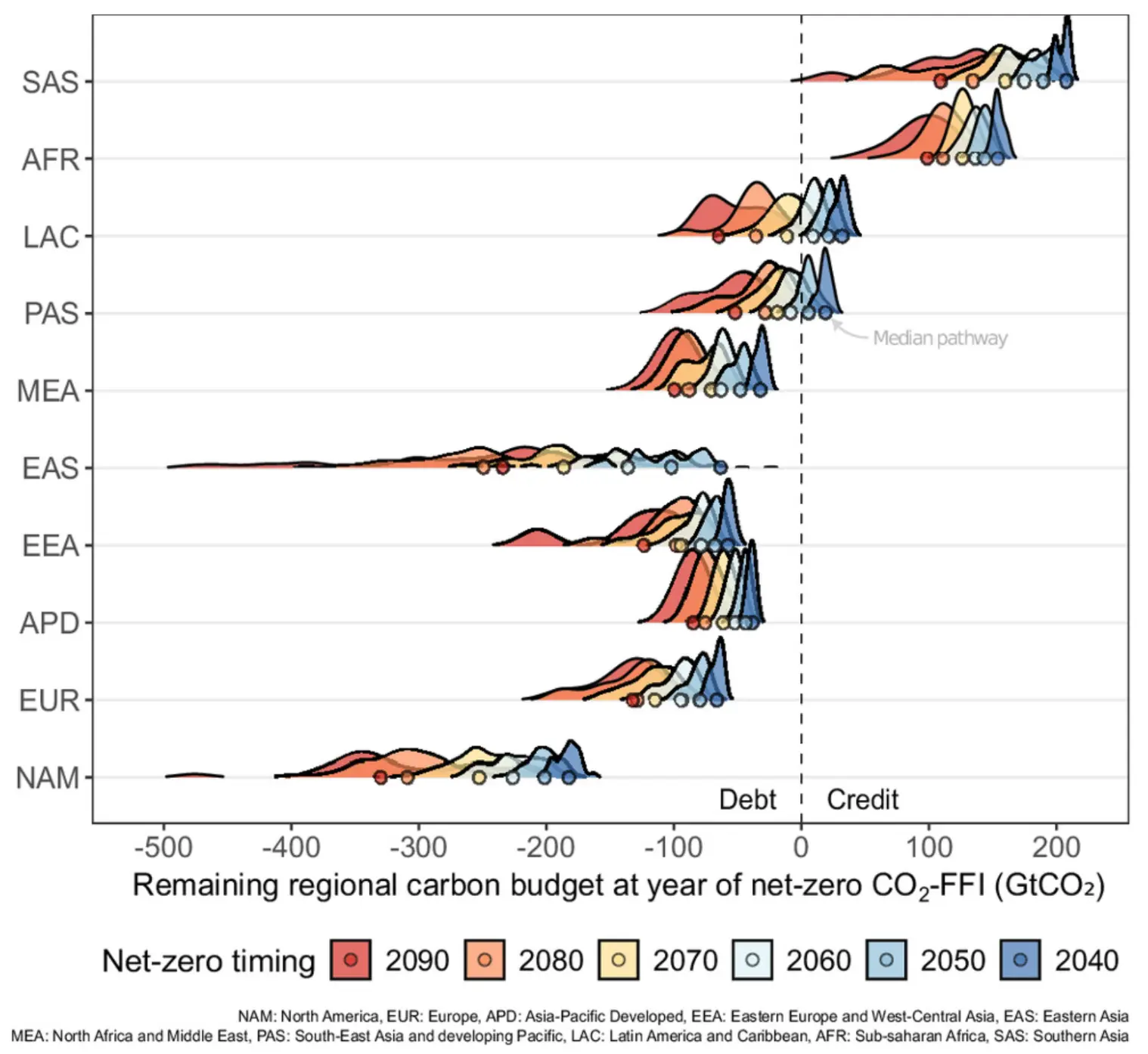

The plot below shows how different regional groups could build up carbon debt under six different timelines of when they achieve net-zero CO2 this century.

It illustrates how sub-Saharan Africa (AFR) and southern Asia (SAS) will not build up carbon debt under any of the net-zero timing pathways.

On the other hand, it shows how a number of regions – Europe (EUR), eastern Asia (EAS), North America (NAM), Asia-Pacific developed (APD), eastern Europe and west-central Asia (EEA) and north Africa and the Middle East (MEA) – will build up carbon debt even if they achieve net-zero by 2040.

Two future scenarios

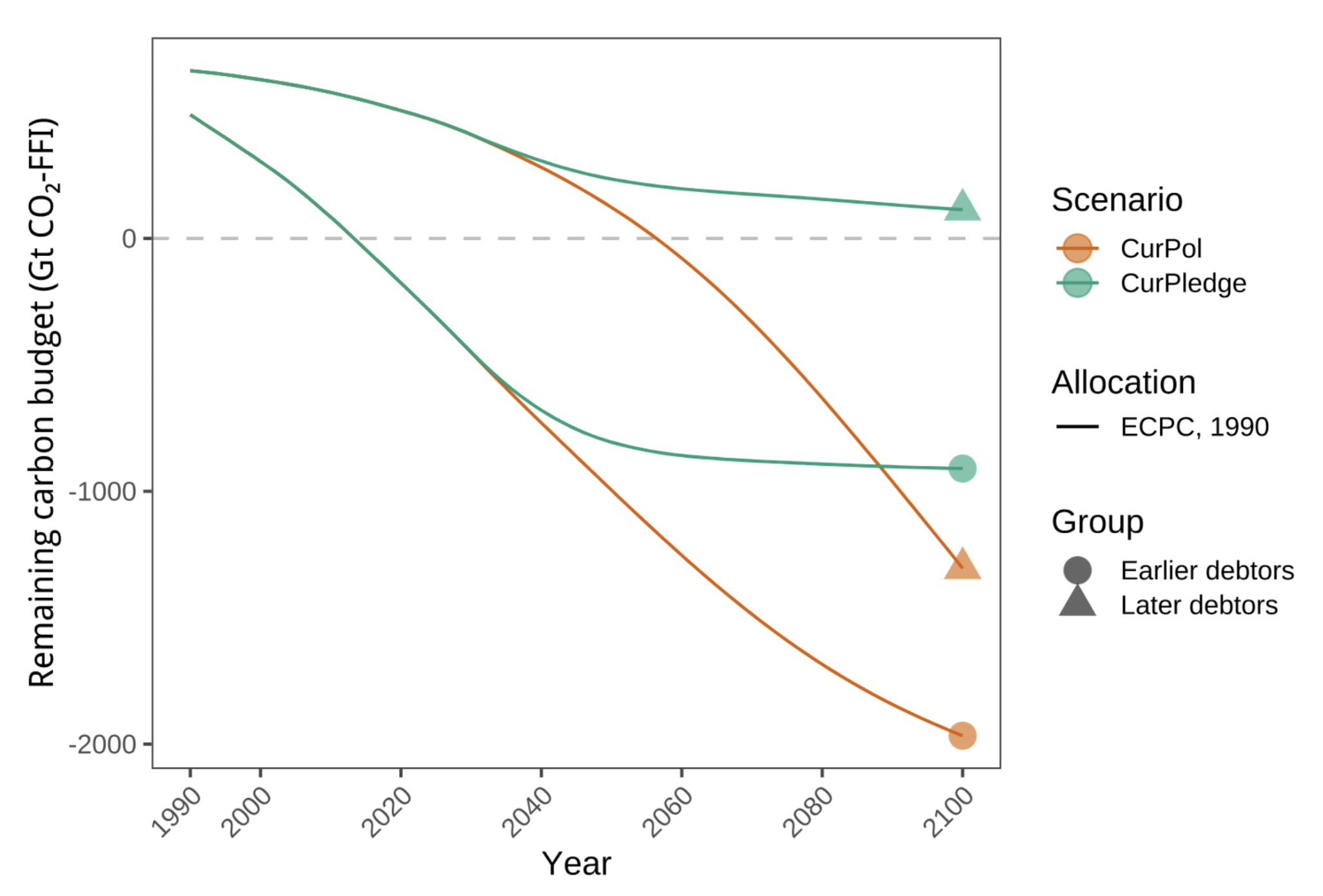

We also apply the net zero-carbon debt measure to two different scenarios of future global emissions.

We look at a current policies scenario (“CurPolicies”), where warming reaches 3C by 2100, as well as a more ambitious scenario where announced pledges and net-zero targets are met (“CurPledge”). In the latter scenario, warming is expected to peak at around 1.8C in 2050.

We find that under the current policies scenario, all regions accrue some level of carbon debt. However, under the current pledges scenario, some regions accrue no debt at all by 2100.

The plot below shows how earlier debtor regions – a group which covers approximately 42% of the global population and includes North America, Europe, eastern Europe and west-central Asia, Asia-Pacific developed, eastern Asia and north Africa and the Middle East – could build up 2,000 gigatonnes of carbon debt by 2100 under the current policies scenario.

Later debtor regions, on the other hand, are projected to avoid carbon debt altogether this century under the more ambitious scenario where nations meet their climate pledges.

Debt burden

The accrual of net-zero carbon debt has major consequences for younger generations.

They will be faced with more frequent and intense climate impacts, while being responsible for reducing emissions and removing CO2 from the atmosphere in order to stabilise global temperatures.

In our research, we explore the burden carbon debt places on a range of “birth cohorts”, stretching from the year 1960 to the year 2020 across both scenarios.

We find that, under the current pledges scenario, the 2020 birth cohort in early debtor regions is expected to experience higher lifetime exposure to extreme heatwaves, compared to what it would experience under a 1.5C reference scenario. In addition, it would face greater carbon drawdown obligations relative to others due to their region’s past emissions.

In later debtor regions, younger generations are also expected to experience increased lifetime heatwave exposure. However, their relative carbon drawdown obligations – and thus their relative responsibility for overshoot – remain low.

Carbon removal

Regions can reduce or compensate for their net-zero carbon debt by cutting their emissions and funding emissions reductions in other countries through international climate finance.

They can also reduce their overall debt burden by removing carbon from the atmosphere.

However, this raises critical questions about how to equate gross carbon emissions with net-negative carbon removals.

Using the climate model emulator known as “FaIR”, and a collection of 1.5C pathways, we find that carbon removal can offset past emissions and reverse warming in the long-term.

However, there is some uncertainty around the effectiveness of carbon removal.

There are concerns that policymakers and scientists may be underestimating the extent to which negative emissions technologies will be required to stabilise global temperatures.

There are also questions around the long-term effectiveness of land-based carbon removal and whether temperature equivalence alone captures regional climate impacts.

Tracking net-zero carbon debt serves as an early warning that every excess tonne of CO2 worsens future harms and makes achieving sufficient net-negative removals even more difficult.

As the world nears the 1.5C threshold, the research provides an approach to measure fair and effective climate action, while highlighting the importance of shared responsibility and bold international cooperation to minimise climate overshoot.

Pelz, S., et al. (2025) Using net-zero carbon debt to track climate overshoot responsibility, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, doi:10.1073/pnas.2409316122