Guest post: How ‘super pollutants’ harm human health and worsen climate change

Multiple Authors

01.22.25Multiple Authors

22.01.2025 | 8:00amWhile the primary focus of tackling climate change is on carbon dioxide (CO2), a group of other greenhouse gases and aerosols – known as “super pollutants” – is having a profound impact on both global temperature and human health.

They are responsible for around 45% of global warming to date, as well as millions of premature deaths each year.

Cutting emissions of these non-CO2 pollutants, which include methane, hydrofluorocarbons and black carbon, is seen as one of the quickest ways to tackle climate change.

Studies have shown how global action to reduce emissions of super pollutants could avoid four times more warming by 2050 than decarbonisation policies alone.

At the same time, it could prevent some 2.4 million deaths a year caused by air pollution.

And, yet, emissions of many super pollutants are soaring.

In this article, we unpack what super pollutants are and why they have an outsized impact on the climate and public health.

The other 45%

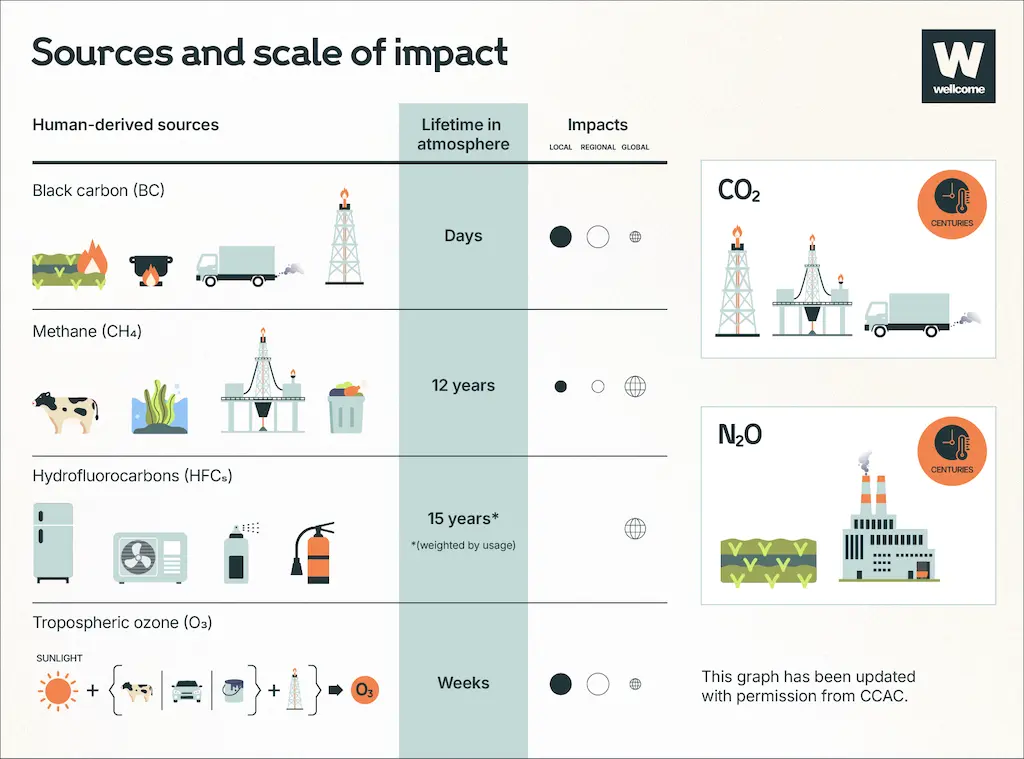

CO2 is responsible for around 55% of global warming to date. The other 45% comes from super pollutants: methane; black carbon; fluorinated gases; nitrous oxide; and tropospheric ozone.

These pollutants are present at lower concentrations in the atmosphere than CO2. But each tonne of these substances has a more powerful warming impact than a tonne of CO2 – up to tens of thousands of times more. As a result, they are still responsible for a lot of warming.

Most super pollutants remain in the atmosphere for less time than CO2, ranging from a few days to a few decades. These are known collectively as “short-lived climate pollutants”.

Others, including nitrous oxide and some fluorinated gases, can have very long lifetimes – even tens of thousands of years in some cases.

As well as being substantial contributors to global warming, super pollutants are a major threat to human health.

Poor air quality caused by these pollutants has been linked to a series of heart and respiratory diseases, as well as lung cancer and strokes.

Methane, black carbon and tropospheric ozone are the super pollutants with the most significant impacts on health.

Methane

Methane is the second-largest contributor to climate change after CO2. In its first 20 years in the atmosphere, when it is most potent, methane has a warming potential more than 80 times greater than CO2.

Methane has both human-related and natural sources. Global human-caused methane emissions come from three main areas:

- Agriculture (~40%), such as from livestock and rice production.

- Fossil fuels (~35%), as a by-product of fossil fuel extraction, storage and distribution.

- Waste (~20%), from food and other organic materials decaying in landfills and wastewater.

Recent research has shown that methane emissions have continued to rise, with “no hint of a decline”. According to the World Meteorological Organization, atmospheric concentrations of methane in 2023 were 265% higher than pre-industrial levels.

Methane impacts public health indirectly in a number of ways.

By increasing atmospheric temperatures, disrupting rainfall patterns and contributing to the formation of tropospheric ozone, emissions of the gas contribute to crop failures which exacerbate food insecurity. The gas has been estimated to cause up to 12% of annual agricultural losses of staple crops.

Increased food insecurity has a number of implications for human health. Research has indicated that nearly half of deaths among children under five are linked to undernutrition. These mostly occur in low- and middle-income countries.

However, the biggest impact methane has on health is its contribution to the creation of tropospheric ozone.

Tropospheric ozone

Tropospheric ozone is among the shortest-lived super pollutants, with an atmospheric lifetime of just days to weeks.

But, despite its short-lived nature, the greenhouse gas has a major impact on human health. It has been linked to around 600,000 to 1 million premature respiratory deaths annually and a similar number of premature cardiovascular deaths.

The greenhouse gas does not have any direct sources, but is formed when hydrocarbons – including methane, volatile organic compounds (VOCs) and carbon monoxide – react with nitrogen oxides in the presence of sunlight.

Concentrations of this harmful pollutant are rising. Soaring emissions of its precursor gas – methane – are believed to be responsible for up to half of the observed increase.

As a major component of smog, tropospheric ozone can worsen bronchitis and emphysema, trigger asthma and permanently damage lung tissue. Children, the elderly and people with lung or cardiovascular diseases are particularly at risk from ozone exposure.

In addition to harming human health, studies have shown that many species of plants are sensitive to ozone, including agricultural crops, grassland and trees. Tropospheric ozone damages plants in many ways, including by entering pores in their leaves and burning plant tissue during respiration.

As a result, ozone emissions are a growing threat to food security.

Black carbon

Black carbon is formed by the incomplete combustion of wood, biofuels and fossil fuels in a process which also creates carbon dioxide, carbon monoxide and VOCs.

Commonly known as soot, black carbon has a warming impact up to 1,500 times stronger than CO2 per tonne. The pollutant dims sunlight that reaches the Earth, interferes with rainfall patterns and disrupts monsoons. Where it settles on snow and ice, it reduces reflectivity and increases melt rates.

Black carbon is a major component of fine particulate matter air pollution (PM2.5), which has been linked to a raft of negative health outcomes, including premature death in adults with heart and lung disease, strokes, heart attacks, chronic respiratory diseases such as bronchitis, aggravated asthma and other cardio-respiratory symptoms.

Each year, around 4–8 million deaths globally are associated with long-term exposure to PM2.5.

While untangling how many deaths are directly attributable to black carbon is tricky, there is growing evidence of its specific health impacts.

Studies have shown that exposure to black carbon correlates with high blood-pressure levels more strongly than PM2.5 overall. Exposure to the pollutant in pregnancy has also been found to impact the development and health of newborn children and is associated with reduced birthweight.

An integrated approach to climate and health

There has been growing political momentum around the threat of super pollutants.

One clear example of this is the Global Methane Pledge, an initiative launched at the COP26 climate summit in Glasgow in 2021. The pledge, which has been backed by 158 countries and the European Union, commits governments to collectively reduce global human-caused methane emissions by at least 30% below 2020 levels by 2030.

However, methane emissions are going in the wrong direction. Emissions are currently on track to increase by 5-13% above 2020 levels by 2030, according to a 2022 analysis from the Climate and Clean Air Coalition and United Nations Environment Programme.

Building awareness of the health consequences of climate change can encourage policymakers to set ambitious limits on super pollutant emissions. It can also underline the importance of a joined-up policy approach to climate and health, where emissions reduction pledges can help spur policies that improve lives.

The Global Methane Pledge and the Kigali Amendment – an international agreement to reduce the production and use of hydrofluorocarbons – are just two pledges that could have immediate and dramatic effects on public health, if fully implemented.

Cutting emissions of super pollutants is one of the most effective ways to “keep 1.5C alive” in the near-term, while protecting health and avoiding tipping points that could cause irreversible shifts in the Earth system.

Combined with the health benefits, rapidly reducing emissions of these pollutants is a clear win-win for people and the planet.

-

Guest post: How ‘super pollutants’ harm human health and worsen climate change