Guest post: How shifting diets away from beef could cut Brazil’s emissions

Multiple Authors

04.24.24Multiple Authors

24.04.2024 | 1:26pmFood systems are responsible for around one-third of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions – and beef has the largest carbon footprint of any food.

Moving diets away from beef and other red meat has become increasingly seen as an important part of mitigating food-related emissions.

But such changes can have unintended consequences, especially for countries that rely heavily on beef production and exports.

In our new study, published in Ecological Economics, we examine the impacts of a gradual reduction in Brazil’s beef consumption on the country’s emissions and economy.

Using an economic model, we find that reducing the average person’s beef intake in line with health recommendations could make up as much as a third of the world’s potential mitigation from dietary changes (according to the UN) – with little impact on Brazil’s overall economy.

Mitigation potential

Research shows that shifts toward plant-based diets can contribute to both mitigating climate change and improving human health.

Meat and animal-derived food production emits more greenhouse gases and consumes more water and land resources than plant-based food production.

Animal-derived food production also results in calorific loss down the food chain. The amount of calories contained in an animal that humans consume is much lower than the sum of the calories of that animal’s food.

For example, of every 100 calories used for sustenance and growth in animals, humans receive between 17 and 30 calories from meat consumption. This loss during the process of raising, processing and consuming animals is due to various factors, including inefficiencies in digestive processes and the physical activity of the animals themselves.

According to the 2019 special report on climate change and land from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), dietary shifts have the potential to mitigate up to 8bn tonnes of CO2-equivalents (GtCO2e) around the world each year by 2050.

In Brazil, approximately 60% of the country’s annual emissions stem from land-use change and agriculture. It is one of the largest beef producers in the world.

In addition, global demand for beef is directly linked to deforestation in the Amazon as forests are cleared to make space for rearing cattle. It is also of global concern, due to the importance of the Amazon as a carbon sink.

Reducing beef consumption

Reducing red meat consumption is crucial not only for mitigating greenhouse gas emissions, but also for improving public health.

Studies have shown that excessive meat consumption can lead to higher rates of cardiovascular diseases, type 2 diabetes and colorectal cancer. According to research from the World Cancer Research Fund and the American Institute for Cancer Research, the ideal limit for red meat – that is, beef, pork, lamb and goat – consumption is up to 300 grams per week per person.

Brazil – along with the US, Australia and Argentina – surpasses this recommended average per-capita meat consumption. Annual beef consumption in Brazil is more than 460 grams per week, according to data from the UN Food and Agriculture Organization and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

Thus, in our study, we set out to reach the recommended per-capita average beef consumption by 2050 – a reduction in consumption of 40%.

We test two scenarios to reduce consumption.

First, we look at relative price changes. We consider a situation where taxes on beef are raised over time from the 2015 average rate of around 8% to approximately 40% in 2050. (Existing taxes on beef in Brazil vary, with specific rates set at the state level.) In a related scenario, we consider what would happen if the funds from such a tax were put towards subsidies for lower-carbon foods.

Second, we look at changing consumer preferences. This could require formal interventions, such as information campaigns and the consideration of culture, emotions and morality. However, it could also occur naturally. Our model does not consider the drivers of the change, but recognises that such a change would occur slowly.

Although there is some movement towards reduced meat consumption due to changing consumer preferences, it remains relatively limited and more concentrated in developed countries. Reasons for this shift in preferences may include higher levels of education and income.

However, in Brazil, meat is viewed as a culturally essential food. In addition, regional preferences differ – for example, there is typically a high beef consumption in the northern region of Brazil, where the Amazon is located.

Despite the international attention linking excessive beef consumption to climate change and Amazon deforestation in Brazil, it has had minimal impact on Brazilian dietary preferences.

Modelling impacts

Our study analyses the impacts of a reduction in beef consumption on Brazil’s domestic market.

We focus on impacts on the country’s economy as a whole, effects on individual sectors such as agriculture and industry, regional impacts and deforestation reduction in the Amazonia and Matopiba regions. Matopiba is a region in the Cerrado, a savannah biome where agriculture has advanced in the last three decades.

The map below shows how Brazil is divided between the Amazon (green), the Matopiba region (orange) and the rest of the country (blue).

We conduct a set of simulations using an economic model for the two regions. In our model, different groups – such as consumers and firms, including investors, agricultural firms, industries and food service – are assumed to make the best decisions based on what they prefer and what they can afford. For firms, the “best decisions” are the ones that minimise their costs, while consumers seek to maximise their “utility”, or satisfaction.

This model represents how the economy works by looking at how people and businesses behave, how they interact in markets, and when the market will reach equilibrium – that is, when supply and demand are balanced.

We use the model to analyse the effects of policies and shocks on different sectors, regions and groups. We present our results as deviations from a baseline trajectory that assumes constant per-capita beef consumption until 2050, with overall consumption growing at the same rate as the Brazilian population.

It is essential to note that the deforestation reduction captured in the model is related to agricultural activity, not to deforestation associated with illegal logging or land grabbing. However, beef and other agriculture drives around 90% of deforestation in Brazil currently, so this is unlikely to significantly change our results.

The latter has various motivations and can be more effectively inhibited through increased environmental monitoring, land demarcation and other mechanisms developed and applied over the last two decades.

Deforestation impacts

We find that a 40% reduction in beef consumption from 2022 to 2050 would help prevent deforestation of approximately 65,000 square kilometres – larger than the area of Sri Lanka.

It also has the potential to mitigate up to 2.8GtCO2e per year, which is one-third of the total mitigation potential from changing diets presented in the IPCC’s special report on land.

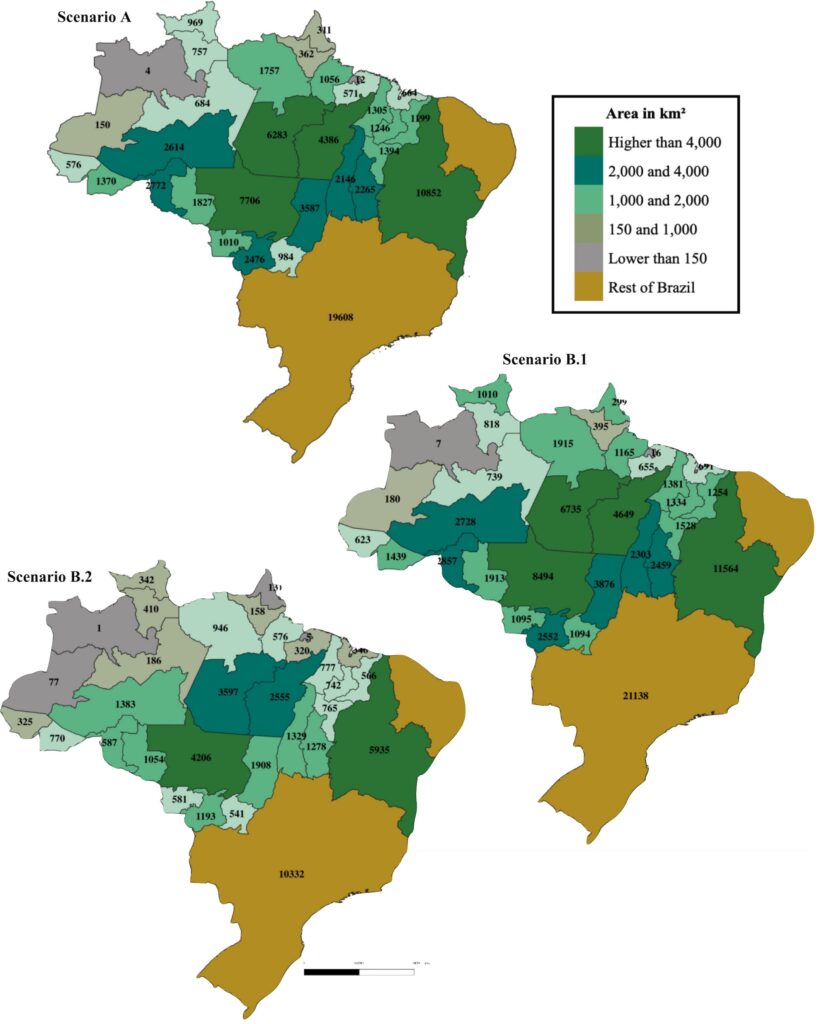

The charts below show the amount of avoided deforestation for the Amazon and Matopiba regions relative to the baseline scenario.

Grey and light green indicate lower amounts of avoided deforestation and dark green indicates the highest amounts. The top, middle and bottom maps show reduced beef consumption through changing consumer preferences, a beef tax and a beef tax with subsidies for other foods, respectively.

In addition to deforestation, we considered the impacts that these shifts would have on Brazil’s economy.

Our findings suggest that dietary shifts due to changes in preferences would have virtually no impact on Brazilian GDP in 2050, reducing it by 0.03% – largely due to a slight decrease in investment.

Adjusting diets through an increase in beef taxes would lead to overall cost increases, resulting in decreases in exports and GDP. We find that GDP would decline by 0.64% in this scenario, with exports decreasing by 1.5%.

However, in the scenario where the beef tax revenue is applied to other foods as subsidies, the national GDP declines by only 0.18%, despite similar decreases in exports.

In all scenarios, we find that the economic impacts would differ from one area of the country to the next. In particular, they would affect regions most dependent on the cattle and beef sector, which are also the most directly affected by the proposed taxation policies. In the beef tax scenario without subsidies, two northern states experience declines in GDP of 3% or higher.

Although Brazilians reducing their beef consumption would bring environmental and health benefits to the country, emissions mitigation cannot be solely Brazil’s responsibility. We observe that the reduction in beef consumption through preference changes leads to a negative effect on the domestic price of beef.

This decrease in domestic prices would, in turn, favour Brazilian beef exports, resulting in less mitigation and a smaller reduction in deforestation. Therefore, it is crucial for this change in habit to be followed by other economies worldwide – notably, those that heavily import Brazilian beef, including China, the US and EU.

Parzianello, L. & Carvalho, T. S. (2024) What if Brazilians reduce their beef consumption?, Ecological Economics, doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2024.108132

-

Guest post: How shifting diets away from beef could cut Brazil’s emissions