Guest post: How COP29 host Azerbaijan could boost growth through climate action

Multiple Authors

11.01.24Azerbaijan’s economy is highly dependent on fossil-fuel exports, making its economic prospects vulnerable to rising emissions-cutting ambition around the world.

As decarbonisation reduces global fossil-fuel demand and prices, the country will not be able to earn as much money from its oil and gas resources.

In a recent study, we looked at the policy solutions Azerbaijan could implement, in order to shift towards cleaner energy and diversify its economy away from fossil fuels to benefit domestic consumers, while remaining competitive in global markets.

Our results suggest that, while being adversely impacted by decarbonisation efforts in countries around the world, it is in Azerbaijan’s self-interest to implement domestic mitigation policies.

With proper sequencing and design of such policies, including a combination of fossil-fuel subsidy reform, a price on carbon post-2030 and use of collected revenue to cut taxes elsewhere, the country could achieve nationally determined contribution (NDC) targets, boost income growth and increase economic diversification.

Moreover, ambitious mitigation efforts towards net-zero by 2060 would yield substantial health co-benefits that could almost fully outweigh the direct economic costs of cutting emissions.

Vulnerability of the status quo

Net fossil-fuel exporting economies, such as Azerbaijan, not only need to implement domestic decarbonisation policies, but also face the consequences of global mitigation efforts if global climate targets are to be met. The latter could substantially impact the country’s future revenue flows from fossil fuel exports.

During the early 2000s, Azerbaijan’s hydrocarbon-fueled economy contributed to rapidly rising incomes and the development of domestic infrastructure. Between 2000 and 2014, per-capita gross domestic product (GDP) in the country increased more than 10-fold, transitioning Azerbaijan from a low-income to an upper-middle-income economy, according to the World Bank.

However, over the past decade, GDP growth has slowed down, while the country’s diversification efforts have not led to major transformations in the structure of the domestic economy, with fossil-fuel activities still playing a central role. Fossil-fuel subsidies in the country remain large and they continue to distort domestic energy markets, according to the International Energy Agency.

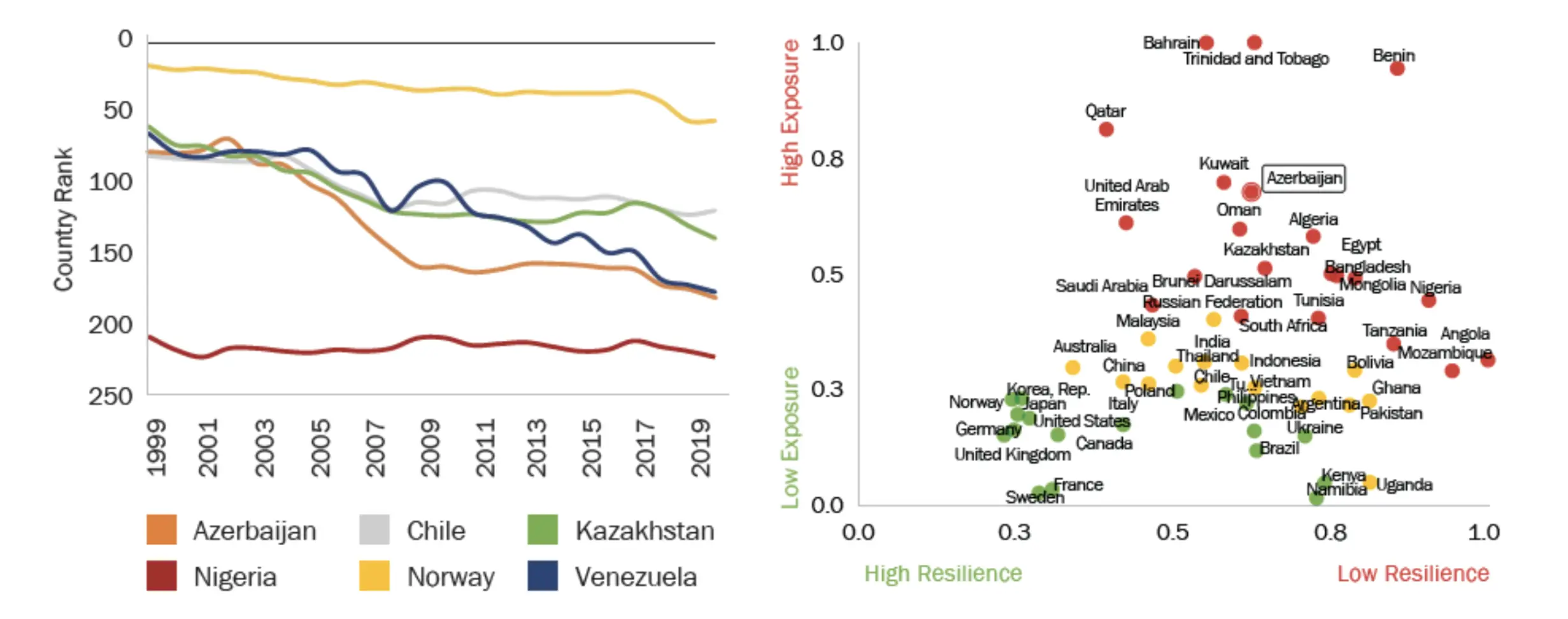

Between 2016 and 2021, Azerbaijan ranked 115 out of 133 countries in terms of the “economic complexity” of its exports – a measure of how diverse a country’s export basket is – according to the Growth Lab at Harvard University.

The figure, below left, shows that its export basket is among the least complex in the world – even among oil and mineral exporting comparator countries, only Nigeria ranks lower than Azerbaijan.

In addition, the country is highly vulnerable to the future energy transition, being characterised by both high exposure and low resiliency, as shown in the figure below right.

Azerbaijan has the second least complex export basket in the world, leaving it highly vulnerable to an energy transition

Economic risks

Without pro-active domestic policies, our research suggests that Azerbaijan risks facing major economic losses from the global energy transition.

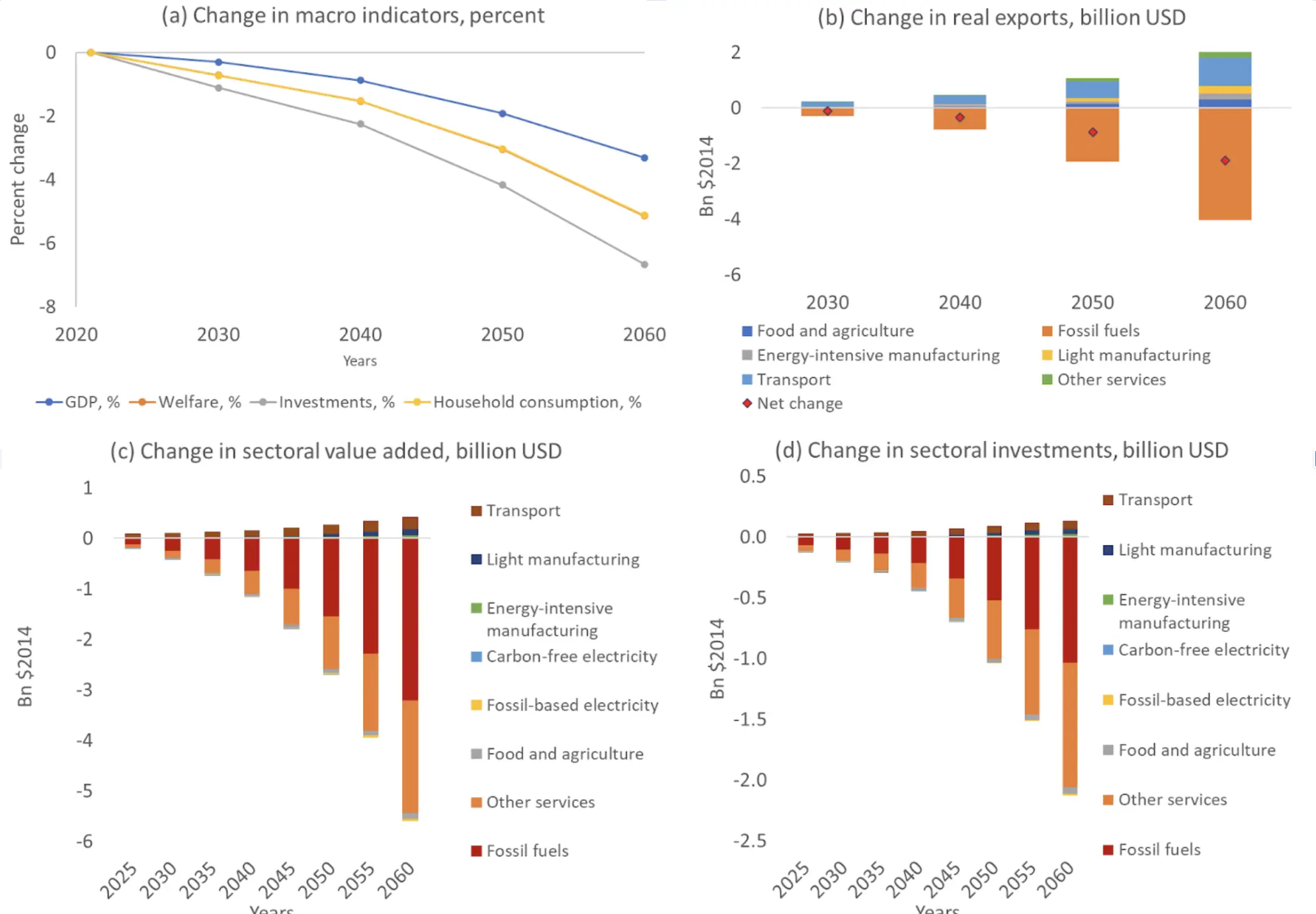

Mitigation efforts around the world can substantially reduce a country’s “resource rents” through declining global fossil-fuel demand and prices, as shown in the figure below.

Results from our study suggest that if countries around the world implement NDC-consistent climate policies, then GDP in Azerbaijan could decline by up to 3.3% in 2060, relative to a reference scenario, which reflects a continuation of the current trends, policies adopted by 2021 and the energy projects that are already in the pipeline.

Households’ welfare, a measure closely related to changes in real income, as well as their investments, might be impacted even more adversely – by 5.1% and 6.7%, respectively, in 2060.

The country would see significant and growing reductions in export earnings from fossil fuels, as shown in the second figure below. Resources such as labour and capital, freed by declining fossil-fuel extraction activities would be reallocated to cleaner sectors, such as services and manufactured goods, which would see a modest expansion in output and exports. However, this would only partly compensate for the reduction in fossil-fuel export revenues, as shown in the figure below.

Global climate action could significantly hit Azerbaijan’s economy

In our NDC mitigation scenario, most of the reduction in economic activity in Azerbaijan is associated with fossil-fuel extraction sectors, as shown in the lower two figures above. Supporting service activities, such as trade, are also impacted substantially. The construction sector would also see a contraction in value-added and investments, due to reduced volumes of investment in the economy overall.

In terms of the government balance sheet, if the rest of the world implements NDC-consistent mitigation policies, then Azerbaijan would see a decline in tax revenue of up to 4% in 2060.

Domestic mitigation is a win-win

Transitioning to a “green” economy is listed as one of the key pillars of the 2021 presidential order titled: “Azerbaijan 2030: National priorities for socio-economic development”.

The country has a target of reducing its greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions to 35% below 1990 levels by 2030 and 40% by 2050, based on its updated NDC from 2023. (Its emissions are currently around 5% above 1990 levels.)

At the same time, between 2010 and 2023 GHG emissions in the country have increased by more than 39%, complicating the ability to achieve the mitigation goals.

In addition, Azerbaijan’s 2050 commitment of cutting emissions by 40% relative to the 1990 level is not only conditional on international support, but could be also deemed as substantially less ambitious than the country’s fair contribution towards global climate goals. Recent research, separate from ours, suggests the latter would imply reducing emissions by around 65% by 2050.

Our research suggests that achieving the stated 2030 targets and further strengthening the country’s mitigation ambition in the long-run would bring important economic benefits.

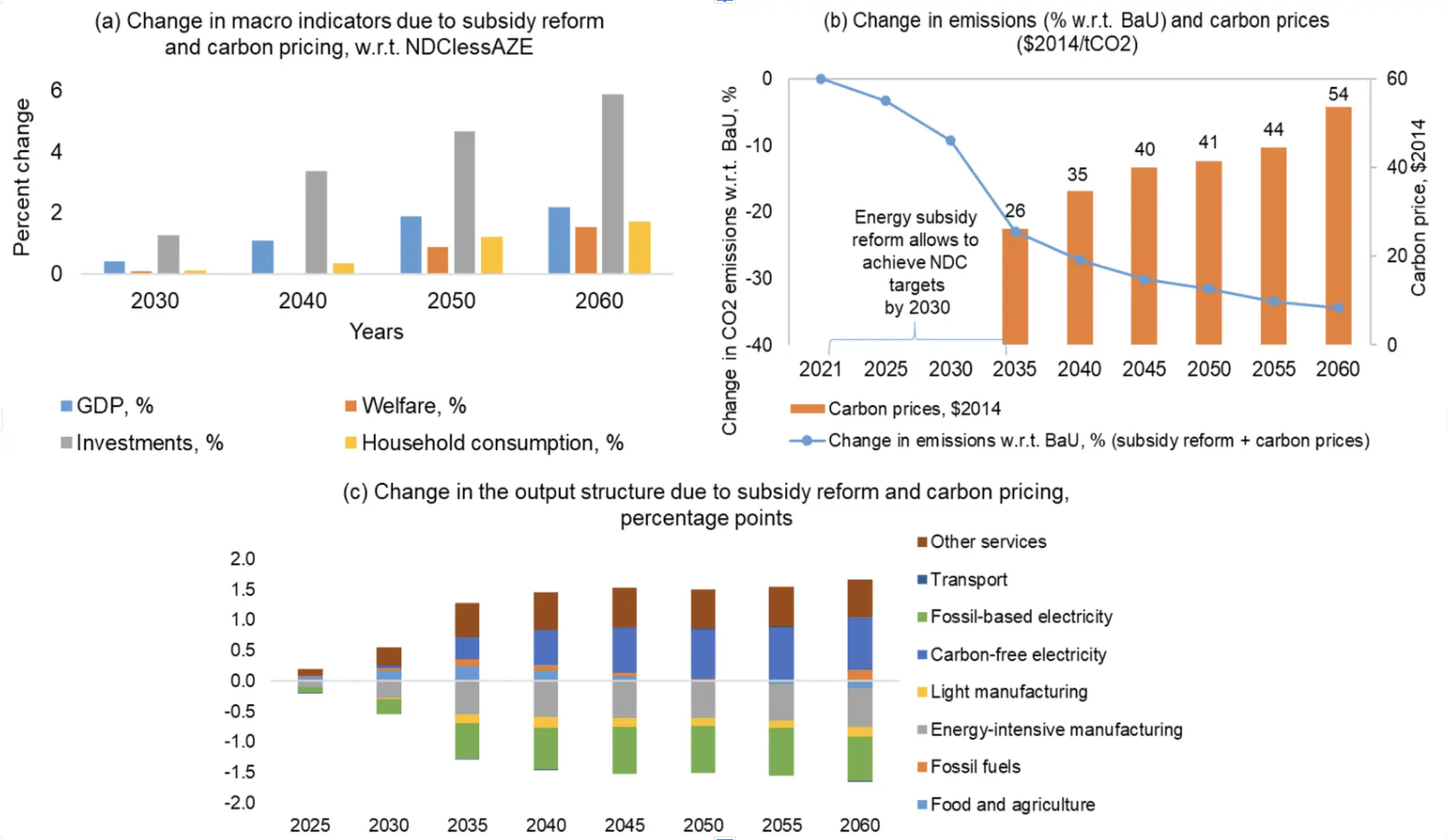

Our estimates suggest that a combination of fossil-fuel subsidies reform, the introduction of a carbon price post-2030 and recycling of the additionally collected revenue via reduced taxes elsewhere – on labour, capital and land, for example – would allow the country to achieve domestic NDC targets while boosting economic growth and investment, as shown in the figure below.

If the country were to implement such policies, Azerbaijan’s GDP could increase by over 1% in 2040 and by over 2% in 2060, relative to the scenario where all countries achieve their NDCs, while Azerbaijan does not implement climate-mitigation policies, i.e. follows the baseline pathway. There would be an even more substantial increase in investment of almost 6% in 2060.

On the policy implementation side, our results suggest that the elimination of two-thirds of fossil-fuel subsidies in Azerbaijan would be sufficient to achieve the 2030 NDC target.

Additional mitigation efforts would be needed to comply with NDC targets post-2030, for example, carbon prices of around $40-$50 per tonne of carbon dioxide (/tCO2 post-2045).

Azerbaijan could boost its GDP through climate action

If additional revenue from energy-subsidy reform and carbon pricing were used to reduce taxes elsewhere, such as taxes on labour, capital and land, this would help to support non-fossil-fuel activities, contributing to the diversification of Azerbaijan’s economy, as shown in the third figure above.

The share of energy-intensive manufacturing in the country’s GDP would decline by around 0.6 percentage points starting from 2035, similar in magnitude to the reduction in the share of carbon-based electricity generation.

These two groups of activities would be primarily substituted by carbon-free electricity and service sectors, reducing Azerbaijan’s exposure to the global energy transition.

Importance of considering a bigger picture

Apart from reducing GHG emissions, domestic mitigation policies would also lead to changes in air pollution levels.

As suggested by earlier studies, reduced air pollution levels could result in lower mortality rates and reduce the overall costs of mitigation.

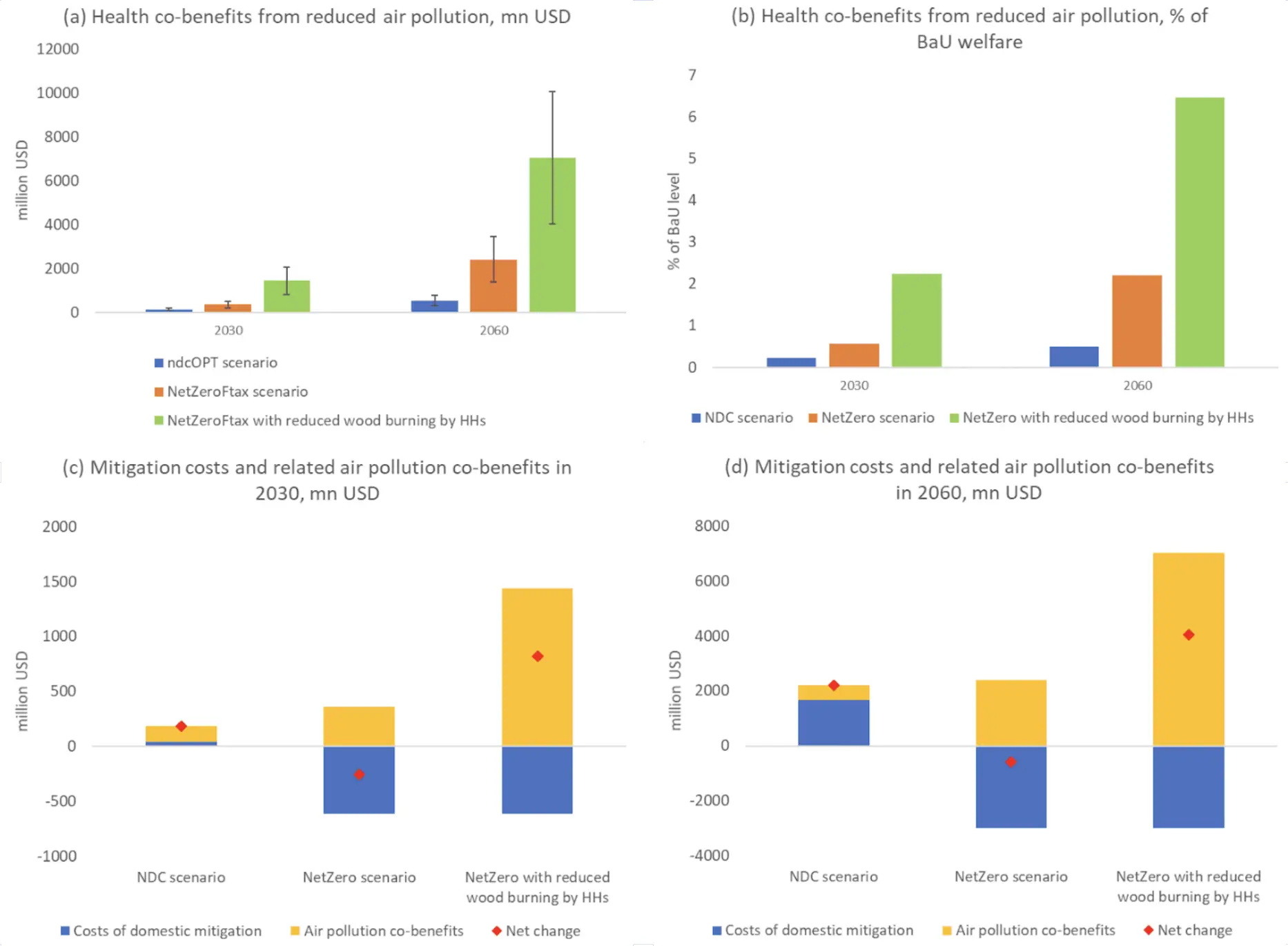

In addition to air pollution changes under the NDC and net-zero by 2060 mitigation scenarios, in our study we also consider a hypothetical case where, within a net-zero climate policy scenario, households reduce the use of wood biomass for domestic heating and cooking – by 50% and 60% respectively in 2030 and 2060, relative to business as usual. (In the figure below, we refer to this scenario as “NetZero with reduced wood burning by HHs”.)

Our results suggest that the improved air quality observed across mitigation scenarios allows for saving between 120 lives in Azerbaijan in 2030 (NDC scenario) and 1,300 in 2060 (net-zero scenario) lives in Azerbaijan.

When the case of reduced wood-burning by households is considered, the number of saved lives increases to 1,200 (net-zero in 2030) and 3,800 (net-zero in 2060).

When these mortality reductions are translated to monetary equivalents using the “value of statistical life” (VSL), the corresponding health co-benefits reach 0.2%-0.6% of households’ welfare in 2030 and 0.5%-2.2% of welfare in 2060, as shown in the figures below.

Health co-benefits could more than offset the cost of Azerbaijan reaching net-zero

Our findings show that households would be better off under the NDC scenario, with air pollution co-benefits increasing the boost to their welfare already generated by mitigation policies.

While there would be direct mitigation-related economic costs to households in the net-zero scenario, health co-benefits would offset 60% of this in 2030 and 80% in 2060.

Moreover, reaching net-zero in 2060 while reducing wood burning by households would bring additional health benefits, with substantially greater economic value than the costs of mitigation.

Policy implications

Several important policy insights follow from our analysis.

First, while being exposed to the declining global fossil-fuel demand and prices that are expected to accompany decarbonisation efforts in countries around the world, our research suggests it is in Azerbaijan’s self-interest to implement domestic mitigation policies.

Our findings support earlier studies that suggest lower risks of “stranded fossil-fuel assets” and overall economic costs for those that move to diversify their economy early, compared to latecomer countries in the context of climate mitigation.

Second, electricity and gas prices are currently well below their economic costs, due to the presence of implicit subsidies. Considering the current windfall earnings from energy sector revenues, Azerbaijan is well-positioned to proceed with the subsidies’ phase-out, as international experience shows that successful pricing reforms are often implemented when fiscal pressures are low.

Our research suggests that a gradual but steady phaseout of fossil-fuel subsidies by 2030, followed by the introduction of economy-wide carbon pricing of at least $25/tCO2 by 2035 is the economically most efficient path to incentivise a clean-energy transition and improve energy efficiency.

From the policy perspective, such a transition would entail a gradual deregulation of gas, electricity and fuel prices, as well as a strengthening of regulators and market mechanisms in price setting – areas where Azerbaijan has achieved limited progress in recent years.

Third, our results support the important role of decisions on the use of revenues collected during the implementation of mitigation policies, either through the elimination of fossil-fuel subsidies or carbon-pricing.

We find that recycling revenue through a reduction in other taxes, rather than direct transfers to households or subsidies to renewable energy, is more economically efficient.

Finally, our results suggest that broader environmental impacts and co-benefits from decarbonisation are an important part of the equation when weighing the economic impact of mitigation policies. This includes reductions in air pollutant emissions, which further lead to improved air quality and declining mortality.

When properly accounted for, such co-benefits could substantially reduce the overall cost of mitigation and even result in net welfare gains in Azerbaijan. Complementary policies on the reduction of wood-burning in the country could result in even more substantial health co-benefits.

-

Guest post: How COP29 host Azerbaijan could boost growth through climate action