Guest post: Gauging the success of climate change adaptation

Multiple Authors

08.21.23As the impacts of climate change materialise around the world, the importance of good adaptation becomes all the more pressing.

Adaptation broadly refers to actions and policies that effectively reduce vulnerability to climate change and encompasses everything from small changes in behaviour to vast infrastructure projects.

However, adaptation is not always a success. There are ways in which it can fail to reduce vulnerability to climate change or even make things worse. This is called “maladaptation”.

As adaptation increases across all sectors of society and parts of the world, it is becoming increasingly important to understand what is – and is not – working.

In our new study, published in Nature Climate Change, we have developed an assessment framework to evaluate the success, or otherwise, of adaptation responses.

We find adaptation options are rarely fully adaptive or maladaptive, but rather can move along a “continuum” based on how it is designed and implemented.

The highest potential for successful adaptation is found in social and behavioural changes, such as diets, food waste and increasing social safety nets, as well as ecosystem-based options, such as nature restoration. The risks of maladaptation tend to be higher for infrastructure, such as coastal defences or water storage.

Our findings, and the underlying framework, are a hopeful reminder that there are ways to assess progress towards successful adaptation – giving us a good grasp on which adaptation options have a tendency to become maladaptive.

Assessing adaptation

So, why do we need a way to assess climate change adaptation? And why now?

Under the terms of the Paris Agreement, countries will undertake a “global stocktake” of progress on climate action every five years. This stocktake includes a request to governments to “review the overall progress made in achieving the global goal on adaptation”.

This year sees the first of these stocktakes, which will conclude at COP28 in Dubai, United Arab Emirates (UAE) in November. The groundwork is already being laid for how it will be structured.

However, reviewing progress on climate change adaptation is not straightforward. This is because adaptation is inherently a local phenomenon – what is right for one location and context may be completely wrong for another. Therefore, making global-scale assessments is challenging.

The research community has a poor track record on tracking and monitoring adaptation outcomes at local, national and international levels, and adaptation is always ongoing.

In addition to these methodological issues, there are growing concerns that collective efforts in adaptation do not contribute sufficiently towards risk reduction, and that, in many cases, they may heighten the risk of maladaptation.

Given this, how do we think about assessing adaptation and preempting maladaptation?

In our paper, we summarise the latest knowledge around assessing adaptation and propose a framework to evaluate its outcomes.

We call it the “NAM-framework” (“Navigating the continuum between Adaptation and Maladaptation) and we use it to examine whether actions done in the name of adaptation are actually reducing climate risk, or inadvertently increasing risk to climate and weather events.

The adaptation continuum

While the aim of adaptation is to reduce climate risk, this is hard to measure, especially when risks are constantly changing – and often escalating – and are sometimes unfamiliar.

The 2022 report on impacts and adaptation from Working Group II (WG2) of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) challenges the dichotomy of risk management actions being either positive (“adaptive”) or negative (“maladaptive”). It suggests instead that adaptation should be considered as part of a “continuum”.

This shift seems subtle, but it emphasises that no actions are inherently “bad” or “good” and that the positive and negative outcomes of adaptation depend on local contexts, processes of adaptation planning and implementation, and the metrics used to assess outcomes. Adaptation outcomes can shift along this continuum when local conditions change or consequences become apparent over time.

Given this context, we reviewed the adaptation literature and all chapters of the WG2 report to establish six criteria to evaluate the potential any adaptation has for adaptive or maladaptive outcomes. This is summarised in the NAM-framework.

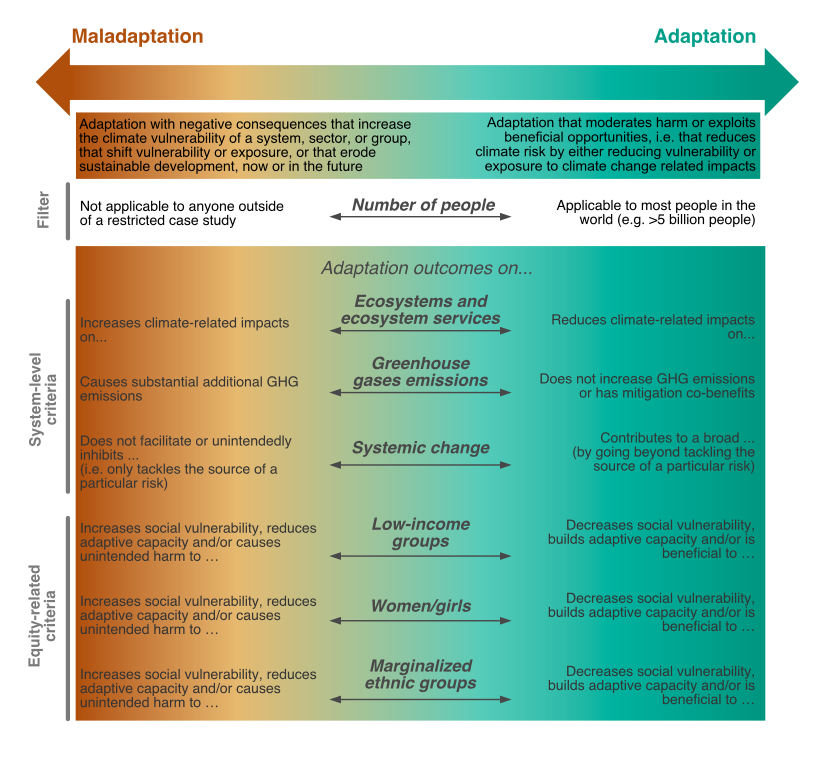

Our framework adopts the IPCC’s recommended continuum, with adaptation and maladaptation at each end. Our six criteria – split into two categories – substantially affect whether an adaptation response has a high risk of leading to maladaptation or has the potential for adaptation.

The first category covers “system-level” criteria. These include:

- 1. Ecosystems and ecosystem services

Whether the adaptation option is likely to negatively affect ecosystems or ecosystem services, have no effect, or have positive outcomes, such as relieving pressures on ecosystems and their services. - 2. Climate system

Whether a particular adaptation option tends to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, have no benefits, or increase GHG emissions. - 3. Social system

Whether an adaptation response offers potential to lead to systemic change. Adaptation with transformational potential goes beyond tackling the source of a particular risk, while incremental actions (only) tackle the source of a risk and aim to reduce it.

The second category covers equity-related considerations. We assess the distributional effects of the adaptation option on marginalised groups – that is, whether an adaptation response was shown to benefit, have no effect on, or worsen the situation of marginalised groups. The groups assessed include:

- 4. Low-income populations

- 5. Women and girls

- 6. Marginalised ethnic groups

The last of these specifically covers people from ethnically marginalised populations, racial categories, castes or other ethnic backgrounds.

This framing – illustrated in the figure below – pays attention to ongoing advances in understanding maladaptation, but also takes into account emerging literatures on climate justice and differential vulnerability.

In doing so, the NAM framework underscores the co-benefits and synergies that adaptation can have for broader goals of sustainable development.

Application

Applying the NAM-framework to a selection of adaptation-related responses, we find that considerable variation exists in the potential for adaptation or the risk of maladaptation. Indeed, actions are rarely fully adaptive or maladaptive.

The highest potential for successful adaptation is found in options relating to social and behavioural systems, such as changes to diets and food waste, and increasing social safety nets, as well as ecosystem-based options, such as nature restoration, farm and fishery practices, and minimising ecosystem stressors.

A higher risk of maladaptation is seen for infrastructural options, such as coastal infrastructure or water storage. Adaptation options, such as insurance, can also have maladaptive outcomes by way of excluding certain vulnerable groups and by fortifying the status quo.

This is illustrated in the figure below, where different adaptation options are scored against the six criteria. The coloured dots on the right-hand side indicate the individual criteria – where green shading indicates a high or moderate contribution to successful adaptation and orange shading shows a mixed, unclear or counterproductive contribution. The central colour scale shows the overall assessment on the continuum from “risk of maladaptation” (orange) to “successful adaptation” (green).

The figure highlights that every adaptation option shows some potential for both adaptation and maladaptation.

We find that more maladaptive options, such as risk insurance and coastal accommodation, can often move towards the successful adaptation end if they address concerns of negative ecological, equity and justice impacts.

Similarly, adaptive options such as social safety nets – welfare services that provide critical support to people during times of economic hardship – can become maladaptive if they do not target the most vulnerable adequately. Thus, how options are prioritised and implemented becomes a key factor in enabling options to move away from maladaptive outcomes.

These outcomes are a reminder that we have ways to assess progress towards successful adaptation, as well as a good understanding on the criteria for designing adaptation efforts that avoid maladaptation.

Both the findings of our research and the underlying framework can be used to inform ongoing conversations around the global goal on adaptation, but also be applied to think through adaptation at other scales, whether it is urban municipalities or locally-led adaptation.

It is our intention that policymakers will use the NAM-framework to assess adaptation interventions and prioritise those responses that reduce the risk of maladaptation.

Reckien, D. et al. (2023) Navigating the continuum between Adaptation and Maladaptation, Nature Climate Change, doi:10.1038/s41558-023-01774-6