Guest post: ‘Fair’ climate-finance flows should be at least $250bn per year

Multiple Authors

12.13.22Global carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions must be roughly halved by 2030 to get the world on track for the Paris Agreement target of limiting warming to 1.5C.

Achieving this will require enormous investment in climate “mitigation” measures, such as increased renewable energy generation to reduce emissions from burning fossil fuels.

While global private and philanthropic capital is available to meet this, the pace of investment has been far too slow. Substantial finance flows from developed to developing countries are needed to redirect these capital flows quickly – and fairly.

Climate finance continued to be a critical point of negotiation at the COP27 climate summit in Sharm el-Sheikh, Egypt, with important progress made on loss and damage.

In a new paper, we explore how different considerations of equity result in different “fair shares” of regional contributions to urgent climate mitigation investment needs.

Agreeing on fairness principles is a matter for the global community to resolve through negotiation.

However, we find that, even using the allocation scheme most amenable to the global north, a “fair” distribution of investment costs would see between $250bn and $570bn each year flowing between regions over the next decade to be consistent with the long-term temperature goals of the Paris Agreement. Most of these flows would be from the global north to the global south.

Cost-effective mitigation

Our analysis takes global mitigation scenarios evaluated by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) in its sixth assessment report (AR6) as a starting point.

These scenarios provide information on where it is cheapest to cut emissions by distributing mitigation investment in a cost-effective manner, based on geophysical, socioeconomic and technological constraints and assumptions.

This is in line with Article 3.3 of the UN Framework Convention of Climate Change (UNFCCC), which says “policies and measures to deal with climate change should be cost-effective so as to ensure global benefits at the lowest possible cost”.

One key output is the range of total investments made into different energy supply and demand measures that can enable society to limit warming to 1.5C or well below 2C.

However, typically these scenarios do not attempt to provide guidance on who should be responsible for funding such investments.

And while cost-effective scenarios help to answer the question of where and when there is potential to mitigate at lowest cost, the optimisation approach itself is not value neutral, as it ignores the fact that regions are currently on a very unequal footing.

Developed countries have so far failed to meet the $100bn they pledged to raise each year to help developing nations tackle climate change. Now, at UN climate negotiations, nations have been tasked with setting a new climate finance target.

There is also growing pressure to align financial flows more broadly with the task of tackling climate change.

Arriving at outcomes that are considered fair by all parties is crucial to make the urgent progress needed to achieve the world’s climate targets. Consideration of equity is therefore needed to guide the implied international financial flows required to operationalise deep mitigation pathways.

Finding ‘fair’ outcomes

Equity is enshrined in the Paris Agreement, which underlines the need to consider “common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capacities, in light of different national circumstances” (CBDR-RC) of all countries.

There is no agreed upon definition of how to estimate or quantify CBDR-RC, and there have been extensive discussions of how to divide up emissions cuts and the remaining carbon budget in an equitable manner.

However, there have been no calculations to date of how to fairly distribute the necessary climate mitigation investments.

We do so by applying approaches from the climate equity literature in line with emerging climate justice principles to the latest IPCC AR6 investment quantifications

We do not attempt to map principles of climate justice (what is fair) to specific equity considerations (how to quantify this), nor do we ascribe one as being necessarily “fairer” than another.

Rather, we focus on describing possible alternatives available to the global community and provide a webtool to explore different “fair” interregional mitigation finance flows.

Billions needed

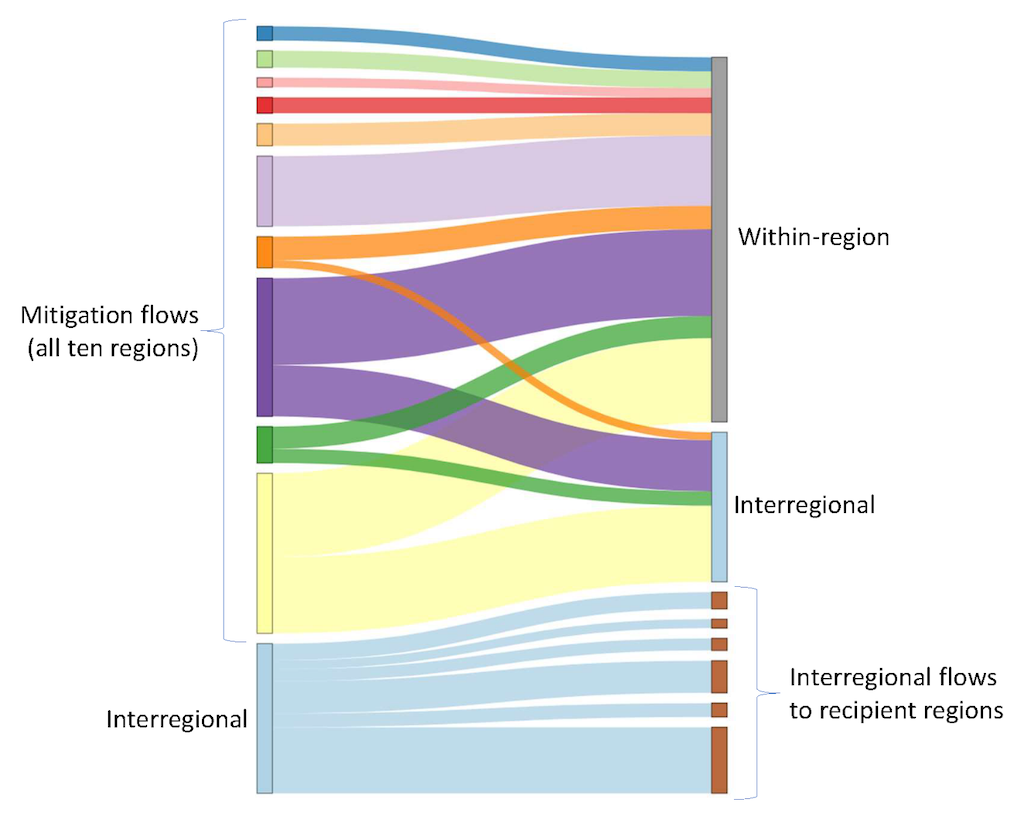

Our analysis provides estimates for how much mitigation finance should flow within a given region, versus how much finance should flow from one region to another in order to achieve a “fair” outcome consistent with the Paris Agreement.

For example, some investments might remain within Europe or they might flow from European countries to African countries. The Sankey diagram below gives an example of such flows.

The resulting estimates of interregional mitigation finance flows rest critically on the equity principle applied, as demonstrated in the chart below.

Ignoring older historical emissions and only counting cumulative CO2 since 1990 is most favorable to North America and Europe. This is because other world regions have experienced much of their industrial growth and resulting emissions in recent decades.

Nevertheless, under this option a “fair” distribution of investment would see mitigation finance flows between regions in the range of $250-570bn annually in the 2020s, in order to be consistent with the Paris Agreement temperature goal.

A full consideration of nations’ capabilities and needs, plus accounting for CO2 emissions since 1850, results in even larger interregional mitigation flows from high-income countries.

A consideration of all the allocation schemes we explore suggests a range of “fair” interregional mitigation finance flows between $250bn and $1.6tn annually over the course of this decade.

Sources of finance

According to the IPCC, global capital markets are deep enough to meet the ambitious mitigation investment needs, but finance needs to be redirected. This needs to happen in all corners, including public, private and philanthropic capital.

Covid-19 recovery and stimulus packages have been shown to dwarf the investments required for climate mitigation, suggesting such levels of finance mobilisation are possible.

Several different instruments are available to drive these shifts, such as grants, loans, guarantees and improved policy and regulatory frameworks.

Other factors to consider include the differences in actual and perceived risk profiles across countries, the large indebtedness of low- and middle-income nations, and the need for fundamental changes within existing financial institutions.

The 2022 Bridgetown Initiative, spearheaded by Barbados prime minister Mia Mottley, calls for reform of multilateral development banks and the International Monetary Fund (IMF). This could help to release large reserves of capital to address urgent climate needs.

As immediate crises in several regions place intense political focus on domestic agendas, our research underscores the need for international cooperation, if emissions are to be cut in line with the long-term goal of the Paris Agreement.

Constructive discourse and interregional cooperation could help to urgently ramp up domestic and international climate finance and stave off the equity consequences of insufficient or slow climate mitigation.

Fair mitigation is a two-part picture. It requires both strong domestic ambition in all countries and international finance to enable equitable effort sharing, and frameworks are emerging to guide this.

Pachauri, S. et al. (2022) Fairness considerations in global mitigation investments, Science, doi: 10.1126/science.adf0067

-

Guest post: ‘Fair’ climate-finance flows should be at least $250bn per year