Guest post: Are UK floods becoming worse due to climate change?

Jamie Hannaford

02.20.20

Jamie Hannaford

20.02.2020 | 5:08pmOnce again, lives have been turned upside down by flooding across large parts of the UK, following the exceptional rainfall brought by storms Ciara and Dennis.

With the flood event still unfolding, it is too early to fully assess its magnitude or severity. But we do know that many major rivers have reached their highest levels on record, with the word “unprecedented” being used widely.

These floods come only three months after similarly devastating – and record-breaking – flooding in Yorkshire and the Midlands. The summer of 2019 also saw more localised, but dramatic, flooding in the Peak District and Lincolnshire.

It certainly seems unusual to have such a cluster of extreme floods – and it feels like the term “unprecedented” is wearing thin. One doesn’t need to look back far to find previous “unprecedented” flooding events.

For example, the winter of 2015-16 saw devastating, record-breaking floods in northwest Britain, with the highest recorded daily rainfall and the highest peak river flows recorded in England.

In the winter of 2013-14, sustained flooding affected southern England – most notably the Somerset levels and the lower Thames. While this event was less exceptional in terms of flood peaks, the duration and geographical extent was remarkable.

The first two decades of the 21st century, in general, have been characterised by many major flood events (see the collected reports produced by the National Hydrological Monitoring Programme).

Inevitably, the current floods – like all floods in recent years – have prompted widespread discussion about flood risk management, as well as lead to claims that floods are increasing due to human-induced global warming.

These claims are, of course, not without reason. But are they justifiable? What is the evidence?

Are floods becoming more frequent or severe?

Here, I focus on river – or “fluvial” – flooding, noting that flooding can also come from surface water, groundwater and coastal sources. To investigate changes in fluvial flooding, we need to analyse long-term records of river flow – sometimes referred to as “discharge” – rather than the level or height of water.

In the UK, we are fortunate to have the National River Flow Archive (NRFA), which collates data from 1,500 gauging stations (such as those illustrated below) monitored by the Environment Agency, Scottish Environment Protection Agency, Natural Resources Wales and the Department for Infrastructure – Rivers in Northern Ireland.

Some of these river flow records go back five decades or more and a significant body of research has used the data held by the NRFA to assess long-term trends in river flow, including flooding. This work has been summarised in review articles, while more-up-to-date trend analyses have also been published.

All of this work points toward the same conclusion. Over the past four or five decades – the length of most typical river-flow records – there has generally been an increase in river flow across most of the UK.

More importantly, in relation to floods, there have been increases in peak river flows (commonly, studies look at trends in the “annual maximum” – the highest peak river flow in each year) and floods have become more frequent.

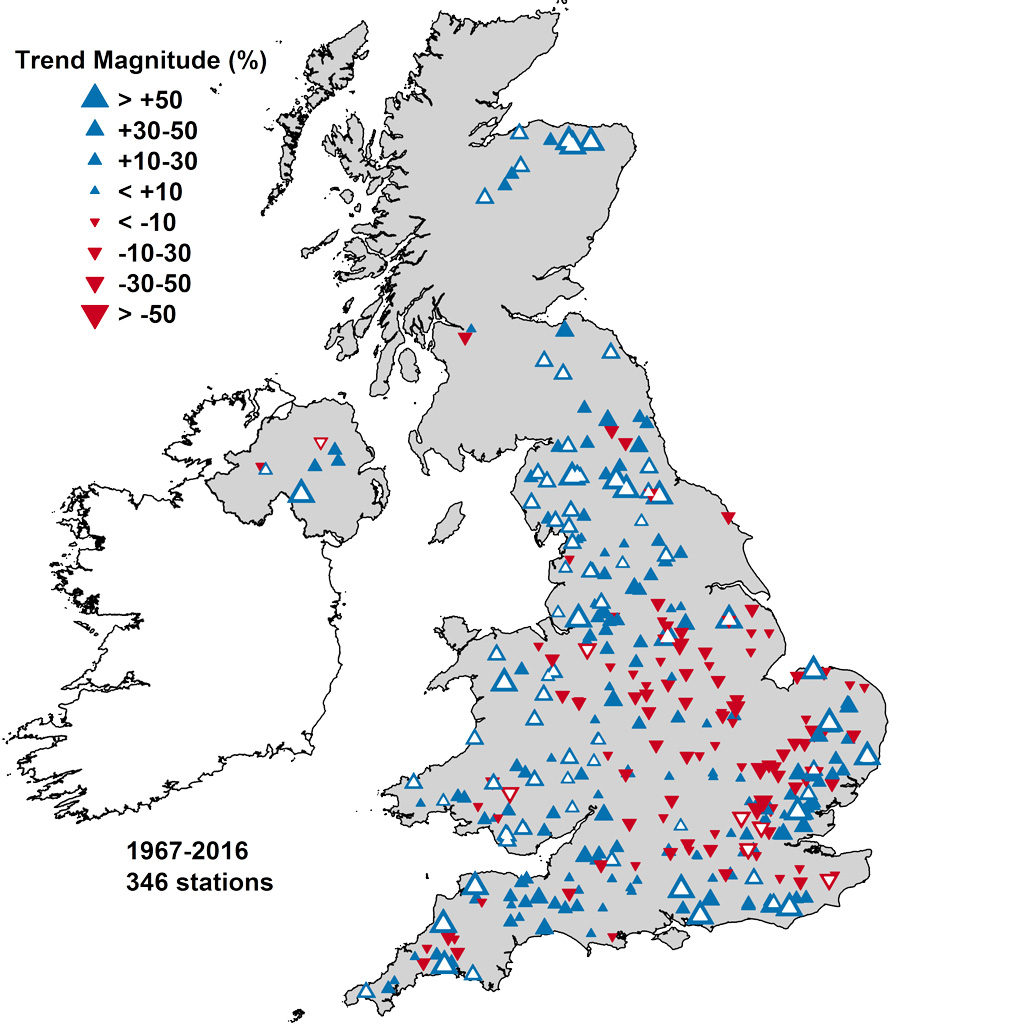

The work is also remarkably consistent in terms of the geographical picture. The map below shows trends in annual maximum flow for 346 gauging stations across the UK. Increases in high river flows – indicated by blue triangles – are most noticeable in the north and west of the UK. There are also significant increases in some other parts of the country, such as southern England and East Anglia.

Note also that there are some decreasing trends – shown as red triangles – although these are rarely statistically significant.

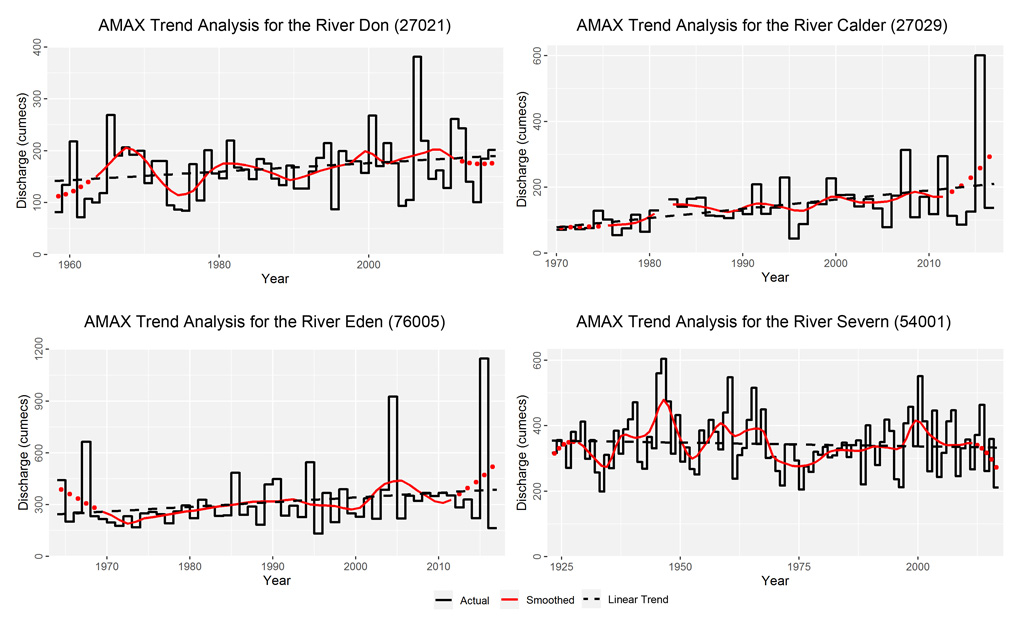

The graphs below show examples of long-term variability in floods in some of the areas affected in 2019-20.

The Rivers Don, Calder and Eden, with records going back to the 1960s and 1970s, show increasing trends, with recent floods, such as 2007 and 2015-16, standing out. (Note that these show trends in annual peak flows using data up to 2017, so do not include the 2019-20 floods. Early estimates suggest these recent peaks will further reinforce these trends.)

However, the record from the River Severn – a rare example of a record extending back to the 1920s – portrays a different story.

While also showing a weak increase since the 1960s, it reveals bigger floods in the pre-1960 period. In fact, this record shows a weak downward trend, albeit with the most prominent feature being notable variability between years and decades, with more “flood-rich” periods in the early 2000s contrasting with “flood-poor” periods, such as the early 1970s.

Are these trends linked to climate change?

In principle, there is a fundamental link between climate change and flooding because, put simply, a warmer atmosphere holds more moisture.

Correspondingly, climate change projections suggest future increases in flood severity are likely for the UK. But are we seeing an impact of climate change in the increased flood trends we have witnessed over recent decades?

Moving from trend detection through to attribution is challenging due to pronounced variability between years and between decades – as can clearly be seen by the “wobbles” in the smoothed red lines on the time series charts above. This “noise” makes it hard to detect any “signal” associated with warming.

Moreover, it is worth addressing what causes these wobbles. At the latitude of the UK, a warming atmosphere generally means more rainfall, but in any one location the effect of a changing climate is complicated by changes to weather patterns. Atmospheric and oceanic circulation patterns vary naturally on a range of timescales, between years and decades – and this is what drives variability in river flows over time.

The UK sits on the edge of the Atlantic Ocean, so this is particularly important. For example, the increases in flooding over the past five decades in northern and western Britain have been associated with changes in the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO), which affects the position of storm tracks across the UK and has a strong influence on rainfall. In collaboration with an international team, we have highlighted the role of variability in Atlantic sea-surface temperatures (the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation, AMO) on European floods.

Research in the UK using very long flood records, such as for the Severn, above, points to pronounced variability between decades, leading to “flood rich” and “flood poor” periods driven by the NAO, AMO and a long list of other factors. These variations make it difficult to interpret trends, so we cannot yet say with confidence how much of the observed increase in flooding over recent decades is caused by human-caused warming, and how much is due to natural variability.

However, as anthropogenic warming influences modes of ocean-atmosphere variability, such as the NAO, the increase in floods certainly reflects a combination of both.

What we can say with some certainty is that there has been an increasing trend in flooding over the past four or five decades in parts of northern and western Britain, and this is consistent with what we expect in a warming world.

Increasing confidence through attribution

Finally, while I’ve deliberately focused here on observational data, any answer to the questions posed must also consider climate models. Disentangling the human-induced warming signal from the noise of variability – known as “climate change attribution” – cannot be achieved by analysing observed flood data alone.

However, it is possible to use sophisticated climate modelling techniques to achieve this for particular extreme weather events. Such attribution studies use models to simulate the climate with and without anthropogenic emissions, and use large collections – or “ensembles” – of these simulations to pin down the contribution of a warming climate.

A growing number of these attribution studies have demonstrated that particular flood episodes bear the “fingerprint” of human-induced warming. For example, studies have showed the 2013-14 floods were made more likely because of human influence on the climate and the contribution of warming to the 2015-16 floods was assessed using similar techniques.

While these studies have focused on individual flood events rather than long-term trends, they increase our confidence that recent increases in flooding have been exacerbated by human-caused warming.

With contributions from Lucy Barker, Katie Muchan, Steve Turner and Simon Williams.