Guest post: A plan to solve the mysteries of Congo’s vast tropical peatland

Prof Simon Lewis

09.03.18

Prof Simon Lewis

03.09.2018 | 2:46pmProf Simon Lewis is a researcher of global change science at the University of Leeds and University College London, as well as a contributing editor for Carbon Brief.

Last year, I led a team of scientists in publishing the first-ever map of a vast peatland in the central Congo Basin. Covering 145,500 square kilometres – an area larger than England – it is the world’s most extensive tropical peatland.

Peat is a type of wetland soil made of semi-decomposed plant matter and so is rich in carbon. We estimate that about 30bn tonnes of carbon is stored in the peatland we found – an amount equivalent to three years of global fossil-fuel emissions.

Given the carbon stored in the peatlands, protecting them has become a global priority. Following our discovery, the Republic of Congo and the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) signed the Brazzaville Declaration – an agreement to protect and preserve the rich ecosystem.

However, while mostly intact and increasingly protected on paper, the peatlands are in reality threatened by road building, logging, drainage for industrial palm oil plantations, and oil exploration. Additionally, rising temperatures could tip the balance of the peatland from absorbing carbon from the atmosphere to releasing it.

The good news is this month we begin “CongoPeat”, a major new £3.7m five-year scientific programme funded by the UK government’s Natural Environment Research Council (NERC).

The programme aims to gain a comprehensive understanding of this carbon-rich ecosystem by answering key questions about its past, present and future.

The past: Why did the peatland develop?

Radiocarbon dating at the base of the peat – up to five metres below the surface – has revealed that the peatland began to form about 10,000 years ago – when central Africa became warmer and wetter as the Earth emerged from the last ice age.

To build on this initial finding, we will take cores of peat and painstakingly reconstruct the past vegetation of the region – using ancient preserved pollen grains trapped in the peat.

Led by Dr Ian Lawson from the University of St Andrews, the pollen analysis will tell us how the peatland first formed and how it has changed.

Prof Susan Page and Dr Arnoud Boom from the University of Leicester will then undertake further analysis of “markers”, such as the chemical composition of wax left on the surface of semi-decomposed leaves preserved in the peat. These markers provide records of changes in temperature and rainfall over time – allowing us to reconstruct the past climate of the region.

This research will enable us to discover how past changes in rainfall and temperature have affected the accumulation or release of carbon in the peatland – and to begin to understand how stable the peatland could be under present and future climatic conditions.

The present: How does the peatland function today?

To better protect and manage the peatlands, we need to know where exactly the peat is, how much carbon the peatlands store and what role they play within the wider rainforest ecosystem.

We can use satellites to map the distribution of different vegetation types, but unfortunately not to detect peat directly – so on-the-ground data is essential.

With our Congolese partners at Marien N’gouabi University, University of Kisangani and the local branches of the Wildlife Conservation Society, we will embark on a series of expeditions across the entire region to take samples of peat and to estimate its depth and carbon content.

Led by Dr Greta Dargie from the University of Leeds, the team will spend weeks in boats and on foot venturing deep into the peatlands – avoiding endemic dwarf crocodiles – to map the peat swamp vegetation, measure peat depths and to bring peat samples back to UK laboratories.

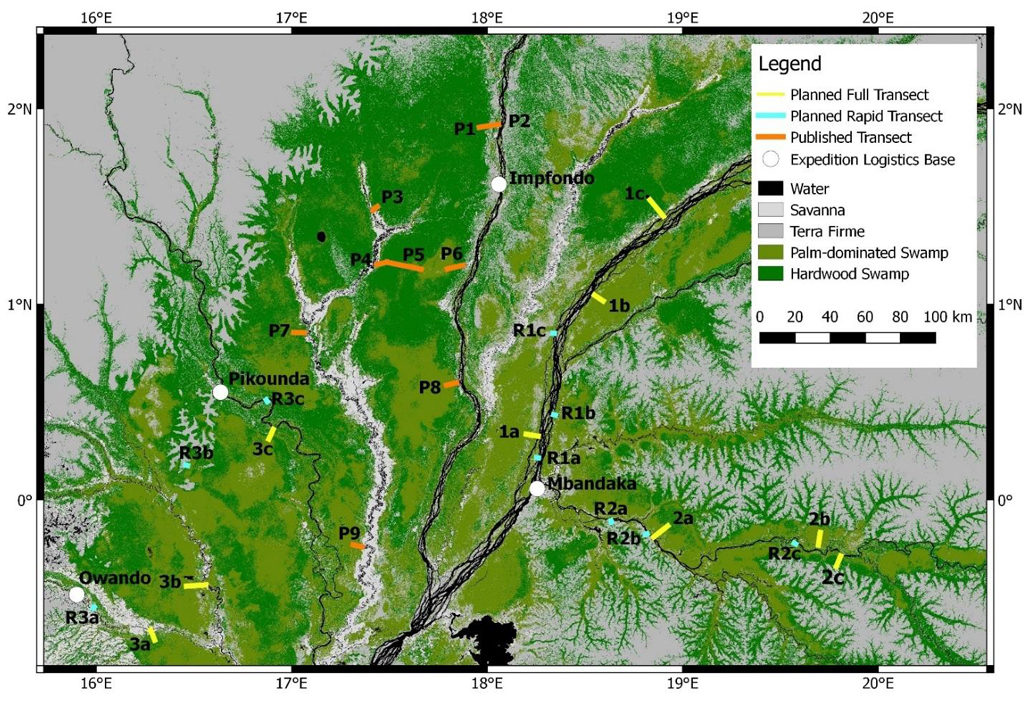

A plan of the three major expeditions the researchers will undertake in the swampy peatlands, labelled 1 to 3. On the map, green shows the peatland; yellow and blue show where the new samples will be taken; orange shows where samples have previously been taken in the Republic of Congo. Credit: Greta Dargie

Then, by combining this information with data from satellites, we can produce new accurate maps for the peatlands.

Critically, our initial discovery of the peatland included no data from the DRC, which we believe houses two-thirds of the peatland area and its associated carbon stocks. Our new work will test this hypothesis and provide the first data-driven maps of the peatlands in the DRC.

Peatlands are important not just in terms of removing carbon from the atmosphere: the waterlogged conditions means these wetlands also release large quantities of the greenhouse gas methane.

Led by Dr Sofie Sjögersten at the University of Nottingham, we will use the expeditions to sample sources and sinks of methane across the region to assess the scale of on-the-ground emissions for the first time.

These measurements will be supplemented by intensive sampling at a well-studied site. PhD students from Marien N’gouabi University will track the flow of carbon between atmosphere, vegetation and peat over the course of two years. The researchers will take monthly measurements of several ecosystem processes, including leaf and woody material inputs into the peat, and their decomposition rates.

Finally, to obtain estimates of carbon stocks and greenhouse gas emissions across the region, all of our ground measurements must be scaled up using satellites. To aid this, we will deploy a drone to get a detailed picture of the topography – the physical shape – of the area.

Led by Dr Ed Mitchard, from the University of Edinburgh, this aspect of the project will establish the importance and role of the peatland in the global carbon cycle.

The future: Is the peatland stable?

To make predictions about the future of the peatlands, we need to use models. Measurements taken by the research team will be used to develop a Congo version of DigiBog – a model that simulates the development of peatland ecosystems.

Led by Prof Andy Baird from the University of Leeds, the DigiBog model will “grow” or “destroy” a peatland depending on the data inputs – such as the amount of carbon from dead plant material added to the soil and the speed of decomposition.

We can use the model to simulate the cutting of trees, allowing us to assess the impact of logging on the peat carbon stocks, or to dig virtual drainage ditches – allowing us to estimate how much carbon will be released if the peat is drained for an palm oil plantation, for example.

However, using DigiBog cannot be used within global climate models. For this we need to add to ongoing global modeling efforts. Led by Prof Richard Betts from the University of Exeter and the Met Office Hadley Centre, we will also make improvements to the UK community global land surface model called JULES (Joint UK Land Environment Simulator) so that it includes the tropical peatland.

This will allow us to investigate how the Congo peatlands will respond to various future climate change scenarios. This will help answer the fundamental question: are these peatlands a new vulnerable tipping point within the Earth system?

Linking to policy

Our project, CongoPeat, aims to provide timely information to policymakers and civil society in a format that is useful to them. Dr Lera Miles, from the UN Environment World Conservation Monitoring Centre, will lead a project translating our scientific outputs into language that can be readily understood by those responsible for the protection and management of the peatlands.

This, plus ongoing support from international organisations including the Global Peatlands Initiative – and from both the Republic of Congo and the DRC governments, the local Wildlife Conservation Society and local communities who live alongside the peatlands – should give our work a lasting positive legacy.

-

Guest post: A plan to solve the mysteries of Congo’s vast tropical peatland

-

Guest post: Answering key questions about the world’s largest tropical peatland