After late night coalition talks, Angela Merkel’s German government has abandoned a planned levy on the oldest and dirtiest coal plants. Instead, it will adopt an industry-backed proposal to pay a small number of lignite power stations to retire.

The levy was part of a climate action plan, launched in December 2014, to get Germany back on track towards its self-imposed 2020 climate goal of cutting emissions by 40% against 1990 levels. The levy was designed to cut lignite emissions by 22 million tonnes of carbon dioxide (MtCO2) each year.

Under the new plan, lignite closures will save roughly half that, with the remainder being made up through other measures. The coal compromise has been welcomed by mining unions. Shares in coal-heavy German utility RWE were up 5% today, as the news emerged. However, critics say the plan will achieve less and cost consumers more.

Carbon Brief lays out Germany’s coal problem and looks at the details of today’s coal compromise.

Germany’s climate gap

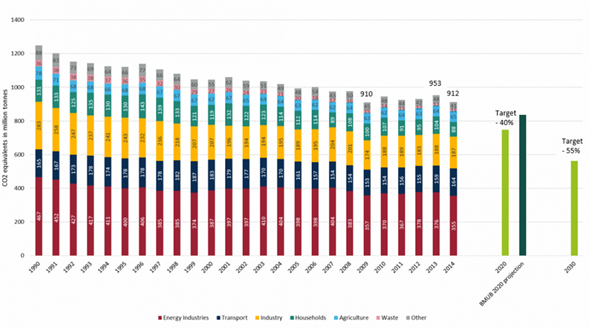

Like the UK, Germany has a self-imposed, unilateral target to reduce emissions in 2050 by 80%, compared to 1990 levels. Both countries have interim targets, with Germany aiming to cut emissions by 40% in 2020. Progress towards this goal has been slower than expected, however.

Government projections suggest Germany will fall short, achieving only a 33% reduction by 2020 (green bars, below right), This is despite its ambitious Energiewende plan to decarbonise the electricity sector by 2050, while phasing out nuclear power.

German greenhouse gas emissions 1990-2014 and its reduction targets for 2020 and 2030. Source: Clean Energy Wire.

The roughly 80MtCO2 climate ambition gap in 2020 is related to Germany’s “climate paradox”, which has seen emissions increase despite rising renewable energy use.

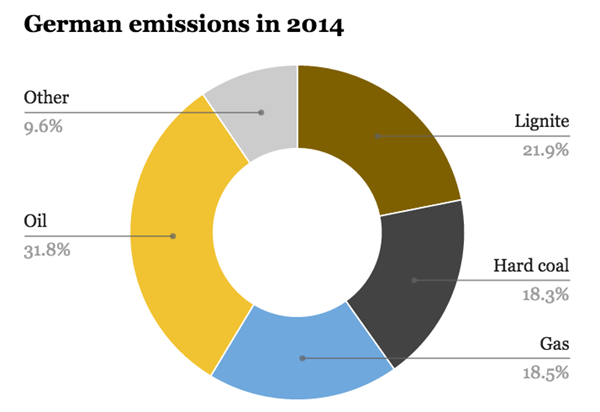

Coal is a big part of this problem. Germany sources a quarter of all its energy needs from coal, making it more coal-reliant than almost all other EU nations. Coal is responsible for around 40% of German emissions (brown and black segments, below). This is the largest share in the G7.

Source: German Federal Environment Agency (UBA).

Power output from coal, and particularly lignite, the dirtiest form of coal, has barely changed in the past quarter-century (brown and black bars, below).

Electricity generation in Germany by source between 1990 and 2014. Source: AG Energiebilanzen (AGEB). Charts by Carbon Brief.

Renewables (yellow, blue and green bars, below) have claimed a growing share of electricity supplies, but nuclear and gas have lost larger shares than coal (below right). Hard coal and lignite supplied 43% of Germany power last year.

Electricity generation in Germany by source between 1990 and 2014. Source: AG Energiebilanzen (AGEB). Charts by Carbon Brief.

Coal levy

The German coal levy was designed to target lignite stations, since they have much higher emissions per unit of power output than any other source. It would have made older plants pay for any emissions above a certain threshold. This was supposed to reduce emissions by 22MtCO2, closing around a quarter of the climate ambition gap towards the 2020 target.

There has been intense pressure from the power sector and unions since the levy was announced earlier this year. They said it would result in mine closures, plant shutdowns and rippling economic impacts on jobs and the economy.

They proposed an alternative to place some lignite stations in a capacity reserve, where they would be mothballed and only called upon to generate power if margins grew tight. They advocated this reserve even though Germany is a large net exporter of power, with a grid that remains substantially over capacity.

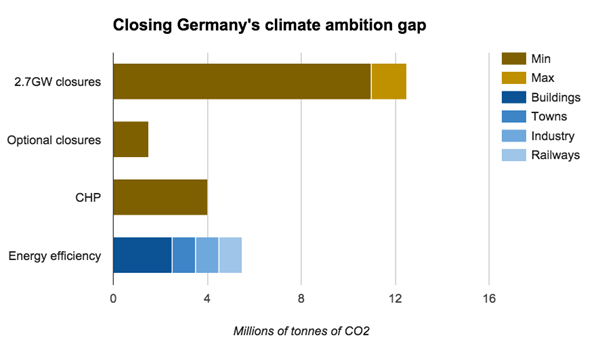

The German coalition government adopted a slightly modified version of this plan after late-night talks last night, with 2.7GW of lignite due to be placed in the reserve. The government says this will lead to around half the originally targeted emissions saving from the power sector (top bar, below).

Source of 22MtCO2 emissions savings under the compromise deal agreed by the German government. Source: German government. Chart by Carbon Brief.

If the retirements fail to live up to expectations, some additional lignite plants will be retired. The remainder of the savings will be made through further investment in combined heat and power plants (CHP) and scaled-up efforts in energy efficiency, the government says.

Coal compromise

Germany has 21 gigawatts (GW) of lignite plant and 28GW of hard coal. So the 2.7GW retirements amount to a small share of the total — 13% of lignite capacity and 6% of total coal capacity.

There is also some doubt as to whether the plants need to be paid to close. Some lignite plants are already 50 years old and facing financial difficulties. Now, instead of facing a coal levy, they will be paid to go into the stand-by reserve.

UK NGO Sandbag says several elderly lignite plants were likely to have retired anyway, and could now be paid â?¬500m to do what they would have done of their own accord. Either way, the coal compromise will be more costly than the coal levy, reports Reuters.

Thinktank E3G says the decision is a “black day for German climate targets, consumers and taxpayers”. It says compromise decision will cost more and deliver less.

WWF Germany says the “bizarre” decision means the original goal of climate protection has been “almost lost”. In a detailed analysis published prior to last night’s decision, it says the additional emissions savings now expected of other sectors can only be achieved if previous plans are significantly strengthened. It says Germany now risks missing its 2020 target.

Until the details of the plan are laid out in legislation, due in the autumn, it is hard to assess how achievable or realistic the compromise plan really is.

Another important part of the agreement is to strengthen Germany’s power grid. Southern states had been opposing plans to build new north-south power lines, needed to send wind power to large cities in the south. The deal will mean some of the cables will now be buried underground.

Conclusion

So does the compromise represent a positive or negative step for the climate? Some green groups are arguing that the decision, while weaker than they hoped, is the first step towards a coal phase-out in Germany.

Chancellor Merkel was instrumental in securing the recent G7 commitment to target a zero-carbon economy in the second half of this century, a shift that implies there is little future for coal. The “climate chancellor” has faced repeated criticism because of Germany’s failure to solve its coal problem, however.

For instance, it has previously balked at the idea of moving away from coal straight away, saying it can’t phase out nuclear and coal at the same time. More than anything else, last night’s messy compromise illustrates how hard it will be to move away from coal — even for some of the world’s richest nations.