Mat Hope

09.07.2014 | 11:25amThe world uses a lot of fossil fuels – and there’s plenty left to burn, if we want to – with all of the world’s major economies still relying on coal, oil, and gas to provide most of their power. But the more countries burn, the more difficult it becomes to constrain global warming.

The trouble is, it’s difficult to quickly swap a fossil fuel based energy system for one that’s low-carbon. It takes considerable time and money to replace coal and gas with nuclear and renewables.

There is a technology that promises to allow continued fossil fuel use while providing emissions cuts, however – carbon capture and storage (CCS). In theory, CCS technology can capture emissions from fossil fuel power plants and lock them underground. That could allow power plants to burn fossil fuels with a fraction of the emissions.

For energy companies and governments wanting to tackle climate change, that’s good news. But the bad news is that CCS has so far struggled to get off the ground, and is yet to be proven in a full scale power plant.

After nearly a decade of false starts, the UK’s CCS industry is slowly getting moving. Earlier this year, the government allocated £100 million to two new demonstration projects. Today, the European Union awarded one of those projects €300 million for its next phase of development. After a long series of disappointments, the industry is hoping all the pieces are in place to make CCS a success.

Potential

It’s increasingly likely that the world will need carbon capture and storage in a big way if it’s going to reduce emissions quickly.

Research by thinktank Carbon Tracker suggests countries have already used about two-thirds of the fossil fuel allowance that will give a good chance of preventing more than two degrees of global temperature rise. That leaves a lot more coal, gas and oil in the ground than Carbon Tracker says can be burned.

And that, in theory, is where CCS comes in. Government advisor the Committee on Climate Change says if the UK is still burning gas in 2030 – a likely proposition – it will be impossible to meet the country’s climate targets without CCS.

While it’s possible to achieve emissions reductions in the 2020s by relying on other low-carbon technologies like nuclear, wind and solar power, excluding CCS makes the task a lot tougher, it argues.

Source: Shell Peterhead CCS project brochure

If that weren’t incentive enough, developing the technology could also save the UK’s economy billions, Professor Jon Gibbons, Director of the UK CCS Research Centre, argues. Gibbons’ centre, based at the University of Edinburgh, is one of two UK university facilities dedicated to improving knowledge about CCS.

He points out that experts suggest hitting the UK’s climate goals with CCS could be £30 to £40 billion cheaper than if it attempts to do so without the technology.

Rolling out the technology could keep the UK’s existing fossil fuel industry running, and allow it to spread into unconventional energy sources such as shale gas – which the current government is keen to explore.

Hence, the government has pledged £1 billion to get the UK’s CCS industry up and running. But despite the government’s support and analysis showing the pressing need for large scale CCS, the technology has so far fallen short of expectations.

Troubled past

For almost a decade, companies have been struggling to get CCS projects off the ground.

Plans for the UK’s first CCS plant – a gas power station in Peterhead, Scotland – were announced in 2005, but the project was cancelled in 2007.

Two further coal plant CCS projects at Kingsnorth and Longanet were announced in 2010. Again, the plans were scrapped within a year.

So, what went wrong? In all cases, the technological challenge was too great and economic conditions turned sour, Gibbons argues.

BP scrapped the Peterhead gas plant project when coal prices suddenly plummeted, making coal use cheap and attractive. While gas remained a key part of the UK’s future energy plans, its emissions are about half the level of coal. As such, the Peterhead scheme quickly “became irrelevant”, Gibbons says – with investors’ attention switching to putting CCS on coal plants.

Similarly, the Kingsnorth and Longanet projects were scrapped when technological issues pushed costs up, and investment became hard to find after the economic crash of 2008.

Despite such stumbles, the government kept an offer of £1 billion of CCS funding on the table.

In February, it signed a contract with Shell for the second of two new CCS projects, with a combined value of £100 million.

Shell’s new project, on the same site as the scrapped 2005 Peterhead project, will capture CCS from an existing gas power plant and pump it into a now-empty gas field under the North Sea.

The other new project, known as White Rose and led by energy company Alstom in partnership with Drax and others, will combine CCS with a new coal and biofuel power plant in Yorkshire. The European Union today awarded the project significant further funding raised through the sale of 300 million permits in the region’s carbon market. Alstom hopes the project can become the centre of a regional hub, with other power plants eventually connecting to its pipeline pumping carbon dioxide under the North Sea.

Energy secretary, Ed Davey, said signing off on the first stage of funding for both projects was a “significant step” towards making a UK CCS industry a reality. He said today’s award was “great news” for the fledgling industry.

New challenges

Both projects still face some big obstacles. But the nascent industry argues it’s a different kind of challenge than CCS has faced in the past.

“Its not been about technology for a long time”, Leigh Hackett, Alstom’s vice president and general manager, told a conference on the future of the UK CCS industry hosted by the Westminster Forum yesterday. The primary obstacles to CCS development are now regulatory, he argues.

In particular, companies need to work out how to link the three key processes involved with capturing, transporting, and storing carbon dioxide.

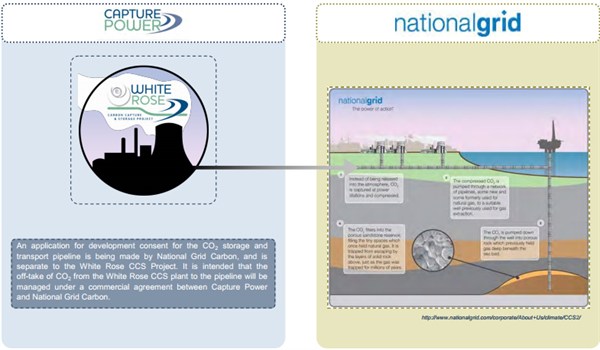

Source: White Rose CCS project scoping report

While capturing gas from industrial processes is a fairly standard process, particularly in the US, transporting and storing it from power plants is yet to be done on a large scale.

That can make investors nervous, because if one part of the process fails – for example, if the emissions fail to be captured – the other two parts could potentially not get paid.

Working out who is at fault if the chain breaks is one of the key areas of uncertainty that needs to be resolved before CCS can get up and running on a large scale, another speaker, Freshfields Bruckhause & Deringer lawyer, Max Cairnduff, told the same conference.

Take the White Rose project, for example, where Alstom and its partners will be in charge of the power plant and capturing process, while National Grid and other partners will build the transport and storage facilities.

There are also environmental concerns to consider. Most importantly, companies need to work hard to ensure pipelines and storage facilities are robust enough to withstand the most extreme and unlikely disturbances.

Scientists and engineers urgently need to better understand how carbon dioxide behaves were it to leak out the pipeline in a concentrated form which makes it easier to transport, Jim Stancliffe, the Health and Safety Executive’s principal inspector, says. He argues that the industry must be able to show the process “is absolutely safe” if it wants to proceed.

New incentives

Despite such challenges, the government remains bullish the new projects will come to fruition. It hopes that new, bigger, incentives will ensure the projects succeed.

The Labour party also threw its support behind the technology in a position paper released today. It promises to ensure “the UK reaps the maximum benefit from its carbon capture and storage potential” through new financing schemes and regulations if it gets elected next year.

A Department for Energy and Climate Change (DECC) spokesperson says that if new CCS projects work, DECC has guaranteed it will sign a lucrative contract for difference with the companies for any power they generate – giving the projects a ‘golden ticket’ into the market.

But while new technology and government incentives should help companies in their quest for workable CCS plants, the main thrust of government’s argument that CCS will work this time is simply that there is no plan B.

The government hopes to get up to 13 gigawatts of fossil fuel power with CCS attached online by 2030. Every year CCS fails to come online makes that goal increasingly untenable, and decarbonising the UK’s economy more expensive.

Moreover, every tonne of fossil fuel that’s burned without CCS contributes to climate change, and makes constraining temperatures ever harder. So the UK’s latest efforts have to work – because time is running out for learning how to make large scale CCS a reality.

A slightly different version of this blog was published on 28th February 2014 under the headline 'Why experts say UK carbon capture and storage must work (this time)'.