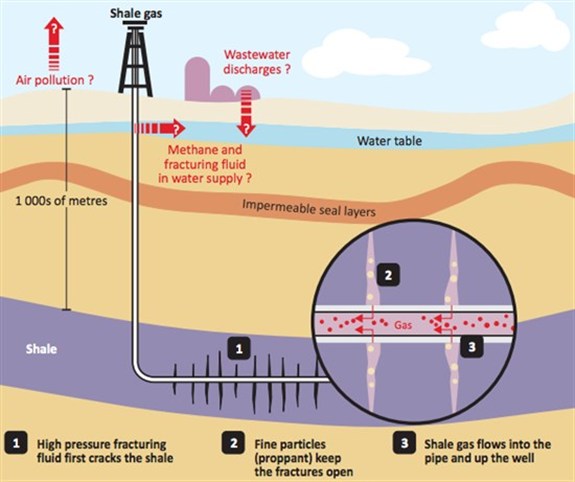

Shale gas is normal gas extracted from shale rock using a technique known as fracking – or hydraulic fracturing.

Protests have sprung up in recent years in opposition to what is sometimes perceived as an unsafe practice. Major studies have been conducted to try and answer such fears. But new research is often met with a mixture of scepticism and spin so has done little to dampen the debate.

Negotiating arguments about fracking from the UK can be tricky. Most of the industry’s experience is in the US, where regulatory regimes are very different, and evidence of fracking’s environmental impact is often contested.

We try to summarise the key questions about shale gas’ impacts and, where possible, draw some conclusions:

- The UK is thought to have large but mostly inaccessible shale gas resources.

- If shale gas replaces coal – and methane leaks are minimised – it could be used as a bridging fuel while decarbonisation happens. But there is limited room for continued use of fossil fuels without CCS if we are to stay within UK carbon budgets.

- Some fears about water pollution are overblown. Surface spills or leaky wells could contaminate water. A lack of water could constrain the industry, and dealing with wastewater will be a challenge.

- Fracking is unlikely to cause earthquakes.

- Shale gas is unlikely to bring down household energy bills.

- Fracking isn’t that noisy, but could cause some local disruption.

- Any health risks are low if fracking is done responsibly.

- Fracking’s impact on wildlife is unclear.

How much shale gas is there?

Estimates of how much shale gas there is outside of the US are currently vague, as there’s not much data to go on.

The British Geological Survey estimates the UK may have as much as 1,400 tcf of gas locked underground. The US Energy Information Administration (EIA) estimates that only 26 tcf may be extractable, however. The UK uses about 3 tcf per year.

The EIA estimates that there’s 7,299 trillion cubic feet (tcf) of technically recoverable shale gas globally. Much of this is thought to be in China – about 1,115 tcf of the EIA estimates – but China has been struggling to develop the resource. Europe is estimated to have about 470 tcf, with 567 tcf in the US.

The bottom line is: we won’t know how much the UK has – or how much can be extracted – until companies drill exploratory wells.

What impact could fracking have on the climate?

Emissions from gas-fired electricity are half those from coal, giving rise to the argument that shale gas can be a clean ‘bridging fuel’ on the road to a low-carbon future. Others argue that methane leaks during extraction make fracking less clean – and maybe even worse than coal.

According to the Committee on Climate Change (CCC) shale gas is better than coal as long as the methane leakage rate is below 11 per cent. Others put the threshold at 3.2 per cent. But again, lack of data is a challenge – leakage rate estimates currently range between 0.6 and nine per cent.

The CCC says the UK power sector should be almost completely decarbonised by 2030 if the UK is going to hit its climate goals. So there’s probably a limited window in which shale gas can be used to generate electricity – unless expensive carbon capture and storage technology gets fitted to power plants.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change concludes that shale gas could play a role in the global decarbonisation effort – but only if it is carried out in a controlled way. Former DECC chief scientist David Mackay concluded: “without global climate policies… new fossil fuel exploitation is likely to lead to an increase in cumulative GHG emissions and the risk of climate change.”

Will fracking contaminate my water?

Some US research suggests fracking has contaminated water supplies but this evidence is often disputed.

Environmental concerns about fracking’s impact on water have been exacerbated by some US firms’ secrecy over the identity and safety of their fracking chemicals. US regulators are now considering disclosure rules.

The regulatory regime is quite different in the UK, where high profile fracking firm Cuadrilla says it will only use four chemicals that are widely used elsewhere and considered safe. UK fracking firms will only be allowed to use chemicals classified as non-hazardous under EU rules on groundwater. DECC expects – but will not require – their identity to be publicly available.

A bigger concern is the potential contamination of water resources through leaky wells or surface spills. UK regulators say they will insist on higher standards of borehole construction to minimise the risk of leaks, but the Environment Agency says surface spills “can and do happen”, even in regulated industries.

Methane in tap water giving rise to images of burning taps made the anti-fracking film ‘Gasland‘ famous. But evidence of fracking-related methane contamination is contested, and it’s thought to be a low risk. In the UK, baseline monitoring of water and environmental monitoring requirements imposed by the Environment Agency should help clear things up.

Dealing with wastewater that becomes mildly radioactive after being exposed to naturally occurring radiation deep into the ground will also pose a challe nge, whether it is processed on-site for reuse or tankered for treatment elsewhere. Technology exists to clean it up, though this is not always used successfully.

CC2.0 darthpedrius

How much water is needed and is there enough in the right places?

Fracking is a water-intensive industry. Water has to be pumped into fracking wells to get the gas out. The UK is likely to have enough water, but it might not be in the right places. The amount of water you need to frack a well depends on the geology of the area and the type of shale rock.

A study for DECC says it takes between 10 and 25 million litres per well. The Institute of Directors estimates peak demand across a UK industry would reach 5.4 billion litres. That may sound like a lot, but it’s only about as much as 35,000 average UK homes.

However, water industry group Water UK says water availability could limit fracking in southeast England’s Weald Basin. Even rainy Lancashire already takes more water from the environment than it should, though local water firm United Utilities thinks there should be enough for fracking.

Will fracking cause earthquakes?

The short answer is: probably not. Research shows fracking very rarely causes earthquakes people can actually feel. A Durham University professor has previously said fracking tremors are equivalent to someone jumping off a ladder onto the floor.

But while fracking may not cause earthquakes, disposing of water used in the process does seem to have some impact. US researchers last year showed pumping wastewater into the rock can stress geological fault lines and lead to mid-sized earthquakes. An article published this year showed a buildup of pressure in wastewater wells was correlated to increased seismic activity. Wastewater disposal by injection will not be permitted in the UK, however.

Are fracking companies noisy neighbours?

Noisy? No. But that doesn’t mean shale gas development won’t cause disturbance. Fracking company Cuadrilla found houses near its exploratory wells experienced noise level of up to about 55 decibels. One US study recorded drilling noise of between 44 and 104 decibels. A normal conversation is held at about 60 to 70 decibels, while a loud violin just tops 100 decibels.

As with any industrial process, there’s likely to be local disruption. Estimates of how many truck movements may be needed to service shale gas wells range between 2,856 and 20,000 for a 10 well development over 20 years. The true figures are disputed. It all depends how much gas can be extracted and whether water arrives on site by tanker.

The industry appears to recognise they need to address the issue. By way of compensation, companies are set to offer communities a lump sum of £100,000 during exploratory drilling plus £20,000 for each well from which gas can be extracted.

Fracking equipment at Preese Hall near Blackpool. Credit: Kennywpara

Does fracking have economic benefits?

Parts of the government certainly think so. The prime minister and chancellor have both talked up shale gas’ potential to boost the economy and bring down energy bills.

The number of jobs the industry could provide is closely tied to how productive wells turn out to be. Estimates range from 15,900 to 74,000 UK jobs, though both figures take a very wide view of what counts as being employed by the industry.

As for energy bills – it’s unlikely shale gas will bring prices down any time soon, if at all. Research suggests shale gas won’t be cost competitive with gas imports for another decade. The International Association of Oil and Gas Producers claims a shale gas boom could bring prices down, but only if about twice as much gas is recoverable as most projections suggest.

Will fracking be bad for nature?

The impacts of the decade-old US shale industry on nature remain largely unknown, recent research suggests. There is wide potential for impacts ranging from pollution (see above) to disturbance caused by noise or on-site lighting during drilling operations.

A major EU assessment found impacts on nature to be plausible and potentially widespread, but lacking a clear evidence base. Nature protection rules will apply to fracking operations, as for any other development.

For instance fracking in or near European protected areas will be subject to additional assessment requirements. About 400 of these overlap with areas available for licensing. Fracking companies will have to meet the same kinds of environmental impact assessments as other developers – Cuadrilla dropped plans to drill and frack at a site in Westby, Lancashire last October because it was close to a population of whooper swans, a European protected species.

Fracking will be allowed in national parks in “exceptional circumstances” despite wide public opposition and despite government spin that protections had been enhanced.

Will fracking cause air pollution or make me ill?

The health and air pollution impacts depend on how well run any future UK industry is. Public Health England says the health risks can be low if fracking is run and regulated responsibly.

In what may become a landmark case a Texan family won a $3 million court battle after saying fracking emissions made them sick. Others say fracking wasn’t the cause.

UK regulators say they will require some air quality monitoring during exploratory drilling but it is unclear if it this will cover all potential pollutants. That’s despite evidence of elevated levels of carcinogenic benzene and other air pollution near some fracking sites in the US. The Environment Agency is yet to draw up guidance on requirements for full-scale shale gas production.

Fracking probably can be done safely if industry standards are high and regulation is robust. The relevant question here is whether they will be. Again, comparing between the US and the UK is difficult because of the very different regulatory environment.