Explainer: Why China’s provinces are so important for action on climate change

Xiaoying You

10.10.22Xiaoying You

10.10.2022 | 8:00amSince China’s president Xi Jinping announced that China would peak carbon emissions “before 2030” and achieve carbon neutrality “before 2060” in September 2020, China’s climate agenda has attracted much attention from around the world.

International diplomats, academics, journalists and analysts alike are keen to find out how China – currently, the world’s largest carbon dioxide (CO2) emitter – plans to translate its ambition into action, a process that is key to the world’s fight against climate change.

China is driven by a top-down political system, with the central government setting out key targets, policies and plans in major areas on a national level. There is a widespread idea that this could smooth – or even guarantee – the path of policy implementation.

However, during the implementation of policies, provincial-level governments are “really important because they are like power brokers in the process of deciding how things go from general statements to actual action”, an expert tells Carbon Brief.

In China, provincial-level governments sit one level lower than the central government – which looks after the whole country – and are peers with national ministries in the governing ranking.

China’s complex governing structure means that its local governments are “more important than many would think”, another expert says.

In this analysis, Carbon Brief explains the features of different regions in China, how they are governed by the central government and the importance of provincial-level governments in the country’s pursuit of its climate goals.

Due to the scope of the statistics Carbon Brief has collected, this article looks at the 31 provincial-level jurisdictions on mainland China. They exclude Hong Kong and Macau, which are China’s special administrative regions and have separate regional governing structures.

- What provinces does China have?

- How much CO2 do Chinese provinces emit?

- What is provinces’ role in China’s climate policymaking?

- How is China governed?

- Why are provinces important?

- How can provinces affect energy transition?

What provinces does China have?

It is hard to overestimate China’s role in the global climate change agenda.

Covering roughly the same landmass as the US, or twice the size of all EU countries combined, China is the world’s most populous country, the second largest economy and the largest current CO2 emitter – being responsible for around 30% of worldwide emissions in 2021.

Domestically, subnational efforts are key to China’s overall drive towards carbon peaking and carbon neutrality, various experts tell Carbon Brief.

“Provinces are really important because they are like power brokers in the process of deciding how things go from general statements to actual action,” says Edmund Downie, who has co-authored a report on the role provinces play in China’s national decarbonisation pledges.

Downie is a PhD candidate at Princeton School of Public and International Affairs in the US. He tells Carbon Brief that the importance of Chinese provinces is “often overlooked” by outside observers because China’s system is “extensively top-down”.

To understand the role of provincial-level jurisdictions in China’s climate agenda, one needs to first understand their different characteristics, the challenges they face in decarbonisation and the various national projects aimed at balancing out resources between regions.

Among the 31 provincial-level jurisdictions on the Chinese mainland, 22 are called “provinces”; four of them – Beijing, Shanghai, Tianjin and Chongqing – are large and important cities known as “municipalities”; and the other five – Inner Mongolia, Guangxi, Tibet, Ningxia and Xinjiang – are “autonomous regions”.

(According to the Chinese government, autonomous regions are areas “with large ethnic minority populations” that “practice regional autonomy, establish autonomous organs and exercise the power of self-government under the unified leadership of the state”.)

The 22 provinces, five autonomous regions and four municipalities are on the same level in China’s governing ranking and enjoy equal governing power. For the purposes of simplicity, this article refers to them as “provinces” and their governments as “provincial governments”.

China’s economic powerhouses – such as manufacturing hubs Guangdong, Zhejiang, Jiangsu and Shandong – are all situated along its east and south coast. As major GDP drivers, these provinces’ annual CO2 emissions and electricity consumption are also among the highest in the nation.

China’s coal reserves are concentrated in the north, particularly in Shanxi, Inner Mongolia and Shaanxi. These three provinces are, in order, China’s three largest coal-producing regions and mine 70% of China’s coal. They form the once-prosperous “coal triangle”.

The three north-eastern provinces – Liaoning, Jilin and Heilongjiang – make up China’s “rust belt”. They were home to the country’s earliest industrial bases but are now in “its biggest economic slump”. At the same time, they are top crop-producing regions.

China’s north-western provinces have a “solid foundation” for heavy, refining and chemical industries, such as coal-to-chemical and oil-to-chemical industries. All of these are described as “dual-high” industries in China, which feature high energy consumption and high emissions. The majority of China’s wind and solar development will also take place in the vast deserts there. (Read Carbon Brief’s guest post on China’s drive to build “gigantic” wind and solar bases.)

The south-west provinces – which sit to the east of the Tibetan Plateau – boast most of China’s hydropower resources. Its fast-growing cities, such as Sichuan province’s capital city Chengdu, have also been propelling a regional economic boom since the beginning of the century. (However, Sichuan – a traditional hydropower hub with a population of nearly 84 million – recently made the headlines for undergoing a “power crunch” caused by a “record heatwave” and drought, highlighting the impact of climate change on China.)

Chinese provinces are big – in size, population and economy.

For example, its most populous province, Guangdong, is roughly three-quarters the size of the UK. But it has 126 million residents, about twice the population of the UK.

Situated in south China bordering Hong Kong, Guangdong has also been China’s biggest province in terms of economic volume for the past 33 years, thanks to its export-oriented manufacturing industry.

Last year, Guangdong’s GDP reached 12.4tn yuan (roughly $1.9tn), big enough to rival that of some advanced economies, such as Canada and South Korea. Its total electricity consumption exceeded 786 terawatt hours (TWh) in 2021, comfortably more than two times that of the UK.

Dongguan, one of the key manufacturing hubs in Guangdong, is billed as the “factory of the world”. According to Chinese state-run media, Dongguan – which was a rural county just four decades ago – produces one in every three toys, one in every five smartphones and one in 10 pairs of trainers globally.

Guangdong and other economically developed provinces in east and south China – each of them home to tens of millions of people – require large amounts of electricity to support their production and daily life. However, they themselves are resource-poor and not able to generate enough power.

(Guangdong was also one of the hardest-hit provinces by power shortages last year. The shortages were driven by an economic rebound, coupled with hot weather and “a lack of initiative” in generating electricity by coal-fired power companies, local media reported at the time. Carbon Brief has analysed the causes behind China’s power shortages last year.)

In comparison, the vast “west China” – a term referring to 12 northern, central and western provinces that occupy about two-thirds of the country – has abundant resources, but relatively weaker economic statuses.

To plug the resources gap and boost economic growth, China’s central government launched a major programme at the turn of the 21st century, called “west-to-east electricity transfer”, to bring coal and hydro power from the resource-rich “west China” to the east – one of the first national projects in China aimed at addressing resource disparities between different provinces.

Three west-to-east corridors have been built to transmit the electricity under the project, according to the state-affiliated National Centre for Science and Technology Innovation; and an estimated 1tn yuan (roughly $150bn) was spent between 2001 and 2015 to build the infrastructure for the programme, official data show.

The “northern line” sends electricity from Inner Mongolia, Shaanxi and other north-western provinces to north China, especially the mega Jing-Jin-Ji metropolitan region, which consists of the municipalities of Beijing and Tianjin, as well as the steel-producing hub of Hebei.

The “central line” pairs Sichuan, Chongqing and other hydro-rich provinces in the southwest with northern and eastern China. Eastern China – including the financial hub Shanghai and its neighbours Jiangsu and Zhejiang – is the most densely populated and economically developed area with the highest electricity demand in China.

The “southern line” provides southern provinces, largely Guangdong, with electricity from Yunnan, Guizhou and Guangxi, which have both hydro and coal power.

This pairing system sees some of the world’s largest coal-fired power plants in remote parts of China supply electricity to economically developed and politically important urban areas.

For example, the Tuoketuo power station in Inner Mongolia – the world’s largest coal power plant by capacity – delivers most of its power to the capital city of Beijing, Yu Aiqun, senior researcher at Global Energy Monitor (GEM), tells Carbon Brief. As a result, Tuoketuo’s CO2 emissions are counted under Beijing’s total emissions, Yu notes.

(With an installed capacity of 6,720 megawatts, Tuoketuo emitted 29.46m tonnes of CO2 in 2018, according to a study. The figure is nearly half of the total CO2 emissions from Belarus that year. A 2019 report said that Tuoketuo’s annual electricity generation accounted for around 30% of Beijing’s annual electricity consumption.)

In 2020, the overall transmission capacity of the “west-to-east electricity transfer” project reached 260 gigawatts (GW) and it saw 2,149TWh of electricity being transferred across provinces – nearly one-third of the country’s total electricity consumption that year – according to China Power News Network. The project’s capacity is expected to grow to 370GW by 2025, the publication added.

China’s other cross-province resource-sharing projects include “south-to-north water transfer”, “west-to-east gas transfer” and “north-to-south coal transfer”.

The last of the three saw the completion of the “world’s longest heavy-haul railway”, the Haoji Railway, in 2019. It is designed to transport coal from Inner Mongolia to landlocked provinces in central and south China – including Hubei, Hunan and Jiangxi – which have high energy demand but are poor in resources, according to CCTV, China’s state broadcaster.

The 1,813-kilometre-long railway starts in Haole Baoji in Inner Mongolia and terminates in Ji’an in Jiangxi.

In January this year, the railway launched its first 10,000-tonne “special” services to “fully guarantee the supply of thermal coal” – one of China’s top priorities this year – CCTV reported. Its transport capacity “could” reach 100m tonnes (Mt) in 2022, a railway spokesperson told the channel. (Carbon Brief has assessed the implications of China’s recent coal push for its climate goals.)

How much CO2 do Chinese provinces emit?

With their fast-growing economy and large populations, some Chinese provinces can emit as much CO2 – the largest contributor to global warming – as some other countries.

In terms of total emissions, the same three provinces lead the pack every year: Shandong, Hebei and Jiangsu.

Both Shandong and Jiangsu are major manufacturing hubs on China’s east coast, with the former also having strong energy, industrial and agricultural sectors. Situated in north China and surrounding Beijing, Hebei is China’s largest steel-producer, with its annual steel production accounting for nearly a quarter of the national total in 2020.

(The steel industry is China’s second-largest CO2 emitter by industry, after power generation and before building materials. A 2020 Carbon Brief guest post examined how steel production drove China’s CO2 emissions.)

In 2019, Shandong, Hebei and Jiangsu altogether emitted 2,656m tonnes of CO2 (MtCO2), which amounts to nearly a quarter of the country’s total CO2 emissions, according to Carbon Brief’s calculations based on statistics from the open-access dataset CEADs.

Compared internationally, this combined volume is so large that it surpasses the total CO2 emissions of India – the world’s third largest emitter – based on the 2019 data released by the Global Carbon Atlas.

According to the World Resources Institute (WRI), Shandong has been the largest provincial CO2 emitter in China since 2003, with its emissions accounting for 10% of the national total in 2018.

Shandong is China’s second most populous province with more than 101 million people, or a third of the whole population of the US. In 2019, its total CO2 emissions amounted to 937m tonnes, according to statistics from CEADs.

Shandong also has the largest installed capacity for coal power in China, which exceeded 100GW as of December last year, according to a government report. Meanwhile, its on-grid wind and solar power generation capacity ranked the third nationwide last December, surpassing 50GW, the same government report noted.

To show the scale of Chinese provinces’ CO2 emissions on a global level and how they have changed over the past two decades, Carbon Brief has produced the animated chart below.

The chart shows the amount of annual CO2 emissions by all mainland Chinese provinces – apart from Tibet – between 1997 and 2019 and compares them to some of the world’s major country emitters. (See the end of the article for a complete list of citations for the statistics used in the charts.)

As the chart indicates, if one compares the CO2 emissions of Chinese provinces with those of major countries, four Chinese provinces – namely Shandong, Hebei, Jiangsu and Inner Mongolia – would have ranked among the top 10 emitters in the world in 2019.

The animated chart shows annual CO2 emissions for the top 10 emitters in each year 1997-2019, in millions of tonnes, based on emissions from fossil fuels and cement. It includes Chinese provinces, four of which rank among the top 10 emitters in 2019. Sources: CEADs and Our World in Data. Animation by Tom Prater for Carbon Brief.As for total annual energy consumption, the top CO2 emitters Shandong, Hebei and Jiangsu – plus Guangdong – are year-on-year leaders.

Statistics compiled by the WRI show that, in 2019, the total energy consumption of Shandong – the number one consumer of that year – made up around 8.5% of the national total, at 413.9m tonnes of standard coal equivalent (Mtce), equal to 12 exajoules or 3,370TWh.

It is worth noting that China does not use total CO2 emissions or total energy consumption as binding targets for its climate change agenda at present.

Instead, it resorts to “CO2 intensity” and “energy intensity”, two measurements that tie emissions and energy consumption with economic growth. “CO2 intensity” and “energy intensity” stand for the CO2 emissions and energy consumption per unit of GDP, respectively.

(China’s updated nationally determined contribution, or NDC, mentions two targets set by its 14th five-year plan, or FYP: an 18% reduction target for CO2 intensity and 13.5% reduction target for energy intensity from 2021 to 2025. Its updated NDC also pledges to cut CO2 intensity by “more than” 65% from 2005 levels “by 2030”. Carbon Brief has analysed both the 14FYP and the updated NDC.)

According to a 2021 analysis titled, “Where is China’s ‘carbon’?”, Ningxia, Inner Mongolia and Xinjiang were the top three provinces in carbon intensity, emitting 51,000, 40,000 and 37,000 tonnes of CO2 for every 100m yuan ($15m) of GDP, respectively. This means that these three provinces – two in north-west China and one in north China – depend on emission-intensive industries to drive their economies. The analysis, published by Chinese news portal Sina in April last year, was written by Zhang Yu, a researcher from the International Monetary Institute at the Renmin University of China in Beijing.

With regard to energy intensity, north-west, north-central and north-east China have some of the highest readings in the country, according to a separate analysis published by Beijing-based Cinda Securities in September last year. This means that energy-intensive industries “are concentrated” in these areas, the piece says.

In particular, the analysis says that the energy intensity of Ningxia, Qinghai and Xinjiang, all in the north-west, is “well above the average” in China. Also, last year, the same three provinces – along with another four provinces – received “red warnings” from China’s state economic planners in June after their energy intensity readings “had gone up instead of dropping”.

As for non-CO2 emissions, China is the world’s largest emitter of methane, a potent greenhouse gas (GHG) with an estimated warming potential of around 30 times that of CO2 over a 100-year timescale.

According to a report by GEM, Shanxi – not to be confused with its neighbour, the northern province of Shaanxi – is the “primary source” of the world’s coal-mine methane emissions.

The report says that Shanxi – China’s largest coal-producing province – emits an average of 13.1Mt of methane every year, “roughly the same amount” as the rest of the world combined.

China is “the world’s largest source” of agricultural GHGs. Direct emissions from agricultural land (nitrous oxide), animal husbandry and rice cultivation (methane) were responsible for a total of nearly 70% of China’s overall agricultural GHGs in 2014.

Crop-planting takes place around the country, but the “rust-belt” province Heilongjiang – which borders Russia – is China’s biggest “food basket” and the largest source of corn, rice and soybean, according to official statistics.

Three provinces – Heilongjiang, Henan and Shandong – produced a total of more than 30% of the nation’s crops last year, Carbon Brief’s analysis of government data shows. They were also the top three provinces in agricultural land size in 2021, according to the data.

Central China’s Henan is the nation’s top animal husbandry province, with more than 10 million people – around 10% of its population – working in the sector.

Henan is famous for both rearing animals, especially pigs, and producing meat. Official figures show that, in 2020, Henan reared nearly 39m pigs and 700m livestock and produced 5.4m tonnes of meat.

What is provinces’ role in China’s climate policymaking?

The importance of provinces in China’s pursuit of its climate goals partially comes from the fact that they are the ones that turn general statements from the leadership into action.

Dr Hu Min is principal and co-founder of innovative Green Development Program (iGDP), a Beijing-based consultancy focusing on “green and low-carbon development”.

Her company has launched an online platform called China Carbon Neutrality Tracker, which aggregates climate and energy-related policies from various subnational governments in China.

Dr Hu tells Carbon Brief that, as China is driven by a top-down political system, it depends on “all provinces and cities” to take “robust” actions to deliver its climate goals. She notes:

“To what extent these actions could be designed and executed is critical for China’s carbon emissions reduction performance as well as global climate safety, given the scale of China’s economy and the status of world’s number one emitter.”

Dr Hu also explains provinces’ role in the implementation of China’s climate policies.

According to Dr Hu, as provincial governors are appointed by the central government, their performances are evaluated by the latter. The central government breaks down the national climate targets and allocates them among provinces.

The targets include “legally binding” ones, such as the carbon peaking time, carbon-intensity reduction rate and energy-intensity reduction rate. They also include “non-binding” indicators, such as the total energy consumption and total carbon emissions.

Some provinces “might” then assign climate tasks “further down” to the cities within their jurisdictions.

Dr Hu adds:

“Implementation of local climate goals will be stringently evaluated and linked to the cadre-performance matrix of subnational government leaders, ensuring that most local leaders would take it seriously and fulfil the goals.

“Since China started to apply this very effective mechanism to execute the legally binding carbon intensity goal in 2011, very few local governments have missed the goals.”

(The cadre-performance matrix mentioned by Dr Hu is an evaluation system used by China to determine the work quality of cadres, or ganbu in Chinese, who are public officials holding managerial positions in the Chinese communist party or government.)

Jiang Xiaoqian, project manager of the climate and energy programme at WRI China, expresses similar views. She tells Carbon Brief that, even though China has long-term visions and goals, to realise them, the country would need concrete actions for implementation. Jiang notes:

“The central government would dissect the goals and pass them down to provinces. Provinces would dissect the goals again and pass them down to prefectures, which would then do the same.”

Chinese officials – such as vice-premier Han Zheng, who heads the national leaders group for carbon peaking and carbon neutrality – have described this working method as “sticking to the goals and dissecting the tasks”. (Read Carbon Brief’s explainer on China’s leaders group for dual-carbon work.)

Jiang says that there are three “most relevant” targets for China’s “dual-carbon” agenda: energy intensity, total energy consumption and carbon intensity.

She notes that the 11FYP (2006-2010) required the reduction of energy intensity; the 12FYP (2011-2015) introduced the idea of carbon intensity; and the 13FYP (2016-2020) brought in the total energy consumption target. Jiang points out:

“The reason why provinces are important is because they act like a link between the upper and lower levels. They are not only in charge of dissecting national goals from the top, but also responsible for distributing tasks down to prefectural-level cities.”

According to Jiang, since China made the carbon neutrality pledge “for the first time” in September 2020, the country has taken “intense” policy actions.

These policies include a series of new targets announced by China’s president Xi in December 2020 to enhance the nation’s NDC. Apart from the 2030 and 2060 goals, those targets required the country to lower its carbon intensity by “over” 65% from the 2005 level by 2030 (compared to the previous target of a 60-65% drop), increase its share of non-fossil fuels in primary energy consumption from 20% to “around’ 25% by the same year, and raise its installed wind and solar capacity to “over” 1,200GW, among others.

China incorporated its “dual-carbon” goals into the national social and economic plan for the first time in the “outline” of its 14FYP. The document was approved at the “two sessions” – a series of important political meetings – in March 2021 and laid out the countries’ social and economic priorities and targets from 2021 to 2025.

In short, the 14FYP set an 18% reduction target for CO2 intensity and 13.5% reduction target for energy intensity over the five years. For the first time, it also referred to China’s longer-term climate goals within a five-year plan and introduced the idea of a “CO2 emissions cap”, though it did not go so far as to set one. (Read Carbon Brief’s in-depth Q&A on the 14FYP.)

After that, China established a national-level leaders group in May 2021, headed by vice premier Han Zheng, to take charge of the “dual-carbon” actions. The leaders group was tasked to lead the formulation of “1+N”, China’s top-level policy framework for its climate actions.

According to China’s climate envoy Xie Zhenhua, the “1” refers to the “guiding opinions” on the two climate goals, while the “N” stands for a series of supporting documents, including the “action plan” for the 2030 peak emissions goal, as well as “policy measures and actions” for “key” sectors and industries. (Read more about the “1+N” framework in Carbon Brief’s China Briefing.)

The “1”, known as “working guidance”, was released by the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China – a political organ consisting of the country’s most senior officials – together with the State Council on 24 October 2021, through state news agency Xinhua.

Two days later, the State Council issued the national CO2-peaking “action plan” to the governments of all provinces, autonomous regions and municipalities, as well as its affiliated ministries and organisations. This implies that all the recipients of the “action plan” were expected to take action, most likely by issuing their versions of the action plan.

Jiang explains:

“How do these policies get passed down to provinces? On the national level, there are ‘working guidance’ and an ‘action plan’. In response, provinces will issue their own plans that will reflect their characteristics.”

For example, in February this year, the government of economically developed Zhejiang province published its “implementation opinions” for the national-level “working guidance”. The province says that it plans to lead its “green transformation” and “dual-carbon” work with “digital revolution”. It explains that it intends to build a “digital and intelligent” governing structure for carbon peaking and carbon neutrality.

The same logic also applies to the 14FYP, where provinces would formulate their local versions according to their own features.

For example, top coal-producer Shanxi has stipulated in its 14FYP that a “green energy supply system” should be “largely formed” by 2025, which would include the “green, smart and safe mining” of coal and the “high-efficiency, clean and in-depth utilisation” of the fuel.

Meanwhile, top CO2 emitter Shandong has pledged to turn “new energy” into a “pillar industry” by 2025 by developing its nuclear, hydrogen and energy storage industries in its 14FYP.

Similarly, Inner Mongolia has said in its 14FYP for energy conservation and emissions reduction – a provincial version of the national 14FYP for energy conservation and emissions reduction – that, by 2025, it aims to cut its energy intensity by 15% compared to 2020 levels and lower coal consumption to “below 75%” of its total energy consumption.

Furthermore, since the beginning of this year, multiple provinces have published their regional 14FYP for “responding to climate change” ahead of the release of a national equivalent, according to Shanghai Securities News.

These provincial climate change 14FYPs not only include detailed targets for CO2 emissions and energy consumption, but also lay out a series of local decarbonisation efforts, such as industry-based transition plans and support for provincial carbon emissions trading, the outlet said in a report in August.

Most recently, on 14 September, China’s Ministry of Ecology and Environment (MEE) – the country’s ecological and environmental watchdog – also issued new guidelines to “all provinces”, instructing them to start drafting their respective action plan for adapting to climate change “as soon as possible”.

The move is part of China’s updated long-term climate strategy, called the National Climate Change Adaptation Strategy 2035, which was published in June.

How is China governed?

Even though China’s political system is top-down – which enables it to “dissect” and pass down goals – China’s governing structure is complicated, which also puts provinces in a key position in implementing climate policies.

The implementation of policies and the willingness of local compliance are important for achieving goals across all political systems, but China is “different” because its governing structure is “fragmented” and “highly decentralised”, UK-based scholar Dr Guo Li tells Carbon Brief.

This is also why local governments – especially the provincial governments – in China are “more important than many would think”, she adds.

(The complex matrix of policymaking and implementation in China was introduced to the English-speaking world by Kenneth Lieberthal and Michael Oksenberg in 1988 in the book “Policy making in China”. Lieberthal and Oksenberg called the Chinese governance structure “fragmented authoritarianism”.)

Dr Guo – who is research associate at the Lau China Institute of King’s College London – says that, in China, an order has to be passed through “all the right lines and levels” before being implemented locally in the end.

She says:

“China, viewed from the outside, is a unitary or Leninist party-state. But this description is a general impression and is not accurate, because that is not how things are done in China.”

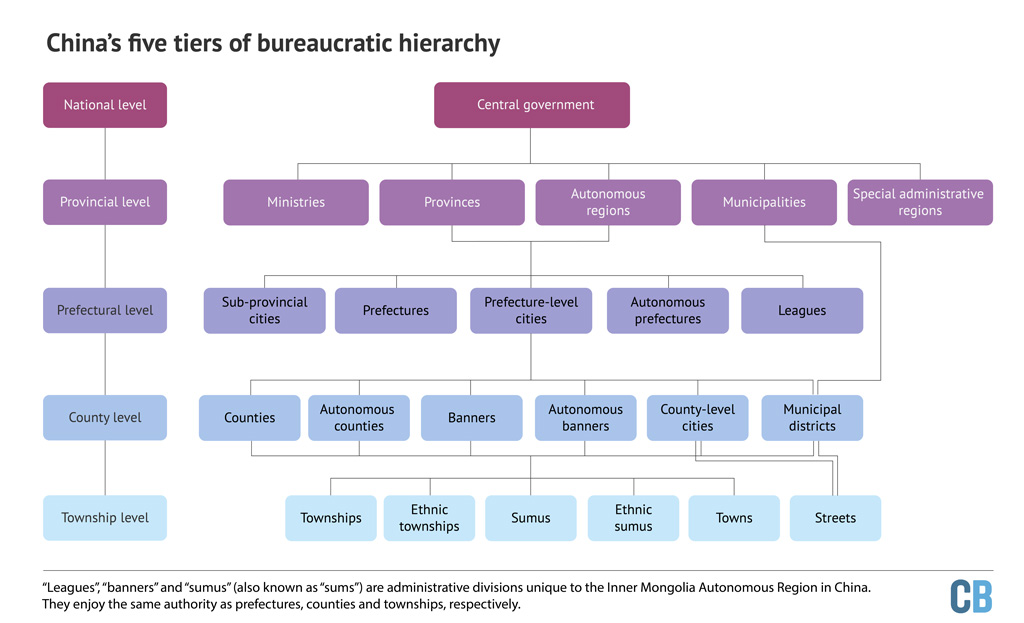

The governing structure of the Chinese mainland is defined by a five-tier bureaucratic hierarchy. They are – from the top down – national-level, provincial-level, prefectural-level, county-level and township-level governments.

The central/national government sits atop China’s policy-making pyramid, owning power over provincial-level governments. Similarly, the provincial-level governments have authority over other local governments.

Communications usually go up and down by just one level throughout the system and units of the same rank cannot give binding orders to each other.

In China, most cities – barring municipalities and some major provincial capitals, such as Guangzhou and Nanjing – are prefectures and have governing power over counties. This is opposite to the hierarchy of the US, where a city falls under the governance of a county.

The central government is run by the State Council, China’s top administrative body, which is managed by the Chinese premier. It directly manages provincial-level governments.

Under the premier, there are several vice-premiers and each of them look after specific affairs, ranging from agriculture to economy. (Currently, vice-premier Han Zheng is in charge of ecological and environmental affairs, according to various reports.)

The State Council consists of a number of ministry-level agencies (currently, 26). These are “horizontally” stretched functions defined by the areas of work and enjoy the same seniority.

For instance, the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) – which is ministry-level – plans the country’s social and economic development, while its peer, the MEE, develops environmental policies and implements pollution-reduction targets.

Each ministry also comprises a number of departments that help it manage national affairs. The NDRC, for example, has a department of environmental resources to oversee environmental-related development and reform. It also supervises the National Energy Administration, which is in charge of the country’s energy industry. Any directives that come from these departments are usually issued in the name of their supervising ministries.

A ministry-level agency enjoys the same seniority as a provincial-level government in China. This means that neither the NDRC nor the MEE, for example, can give binding orders to the provincial government of Shandong or the municipal government of Shanghai. Instead, any orders for the latter two must come from the State Council, their direct superior.

All national ministries have regional offices along the five-tier hierarchy, such as the department of ecology and environment of Guangdong Province, which is a provincial offshoot of the MEE.

Below is a framework showing China’s five tiers of bureaucratic hierarchy.

According to Prof Zhou Zhenchao, dean of politics and public administration of the Southwest University of Political Science and Law in China, the central government’s direct affiliates – meaning the ministries – deal with “dedicated affairs” from the central level; while “most other” domestic affairs are managed “jointly” by the central and local governments with the latter taking charge of the actual implementation.

Prof Zhou wrote in an essay that China’s governing method is “a combination between vertical management and multi-layered local management”.

He added that the relationship between China’s “vertical” governance – the top-down chain from the central government to the local government – and its “horizontal” governance – as in how far the power of provincial and other local governments stretch among their peers – are so complicated that “it is unique in the world”.

Why are provinces important?

Under such a “fragmented” governing structure, there are four main reasons why provincial governments’ actions are important to China’s overall climate goals.

First, it is the provincial governments, not ministries, that have real power over ministries’ provincial branches and, therefore, directly influence their implementation of policies. This is due to a unique twist in China’s governing structure that gives provincial governments more power over ministries.

Second, provincial governments are in charge of generating their own revenues and providing budgets and other resources for implementing national policies, such as the “dual-carbon” targets.

Third, as the most powerful of all local governments in China, provincial governments could be in a position to negotiate and bargain with the central government over the implementation of climate and energy policies, which could determine the speed of China’s decarbonisation.

Finally, provincial governments run companies and many of them are in key industries, such as power generation and technological innovation. Together with provincial governments, state-owned enterprises are the “main implementing bodies” of China’s climate agenda, an expert tells Carbon Brief.

The first factor is the result of China’s political reforms since the late 1970s, according to Kenneth Lieberthal’s classic essay about China’s environmental governance. He said that, “in general, territorial governments have become more powerful and the central-level functional units such as ministries have had their wings clipped”.

Take the Department of Ecology and Environment of Inner Mongolia, for example. On paper, it should be a devolved provincial-level function of the MEE. However, the department technically answers to the provincial government of Inner Mongolia and is only “guided” by the MEE.

This governing quirk is mostly driven by the fact that the provincial government of Inner Mongolia manages the human resources and budget of the Department of Ecology and Environment of Inner Mongolia, explains Dr Guo of the Lau China Institute. In other words, the former is in charge of promoting and paying for the staff of the latter and, ultimately, holds power over it.

According to Dr Guo, since China opened its doors to the world in the late 1970s, the prime concerns of Chinese provincial governments have also been driving economic growth and maintaining political stability through social stability.

This reporting line means that, from an organisational perspective, provincial-level ecological and environmental departments, for instance, are “responding not to mandates that the MEE puts out so much as weighing MEE mandates against provincial government priorities that may reflect, for instance, a stronger focus on economic development”, says Princeton PhD candidate Downie.

This is also exactly why the central government has sent out the “Central Ecological and Environmental Inspection Teams” to “point out flaws by provinces” and why those teams are so powerful, Downie notes, adding:

“These inspection teams do not, in fact, have a chain of command between the MEE and the local bodies.”

(Carbon Brief’s Q&A has explained who these inspection teams are, what they do and how they might impact China’s climate agenda.)

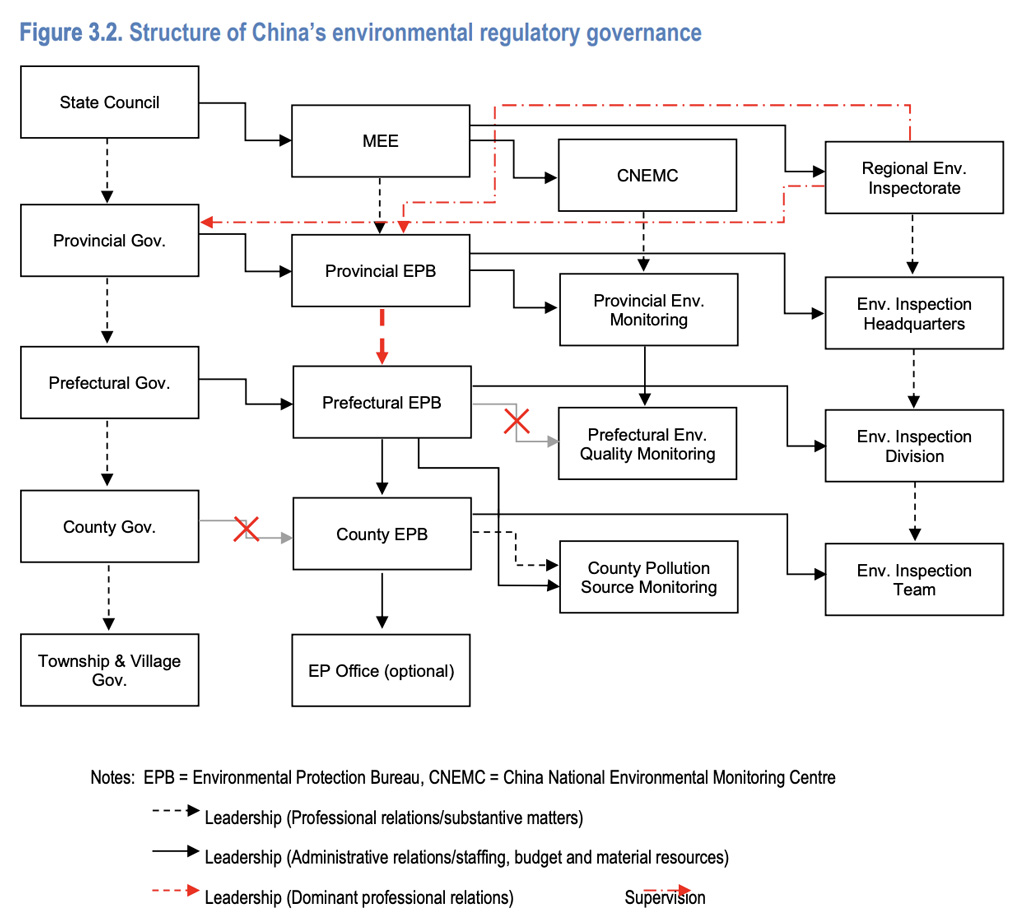

The chart below is part of a paper, written by Chan Yang and published by the Organisation of Economic Co-operation and Development in March 2020. It shows the complex – and often confusing – structure of China’s environmental regulatory governance.

As the chart indicates, while the provincial environmental protection bureau – which is now officially known as the provincial department of ecology and environment – is under the leadership of MEE on “substantive matters”, it is also under the leadership of its provincial government over “staffing, budget and material resources”.

China has not yet developed a separate regulatory structure to deal with climate-related targets and it remains unclear if it will. However, the chart illustrates a general idea of the chain of command on environmental issues, which often overlaps with climate issues.

In addition, Chinese provincial governments are in charge of generating their own revenue, which provides them with incentives to favour high-profit investments that are often emissions-intensive and energy intensive.

Downie tells Carbon Brief that, since the mid-90s, provinces have had to “mostly rely upon their own money” to fund themselves. He adds that Chinese local governments “have to raise their own money in order to do the things the central government wants them to do and to do the things they want themselves to do”.

Therefore, in the course of pursuing climate-related targets, most of the time, provincial governments have to come up with their “resources” to address the cost of doing so, Dr Guo points out.

She notes that these “resources” refer to not only budgets, but also “all sorts of supportive policies”, such as the local employment and social costs. They can also cover, for instance, the facilities needed to support the innovation of the renewable energy industry.

This “find-your-own-resources” governing model is copied throughout the Chinese governing structure, from the provincial to the township levels.

Furthermore, provincial governments split the taxes they collect with the central government, due to “substantial” fiscal and tax reforms launched by the central government in 1994. This means that allowing large-scale investments, such as coal-fired power plants, can potentially bring higher incomes for the governments.

“So the things that might affect their economy and their tax revenues are things that might weaken their ability to achieve other kinds of aims,” says Downie.

Meanwhile, from the perspective of policy implementation, China’s “decentralised” system means that provincial governments can often carry out negotiations and bargaining with the central government in their best local interests, especially in driving the economy and increasing provincial incomes.

Yu Aiqun of GEM describes such negotiations and bargaining as the “counterforce” from the provincial government to the central government.

Yu says that the provincial governments are able to “challenge” the central government in matters such as developing the coal industry, using the local economic development or employment rates as bargaining chips. And such a “counterforce…may change or slow down the speed of energy transition,” she explains.

Yu adds that, while goals such as the “dual-carbon” targets will indeed be “dissected” and passed down the command chain, there is currently a “severe rebound” from local governments to put coal ahead of climate targets.

She notes that some provinces are “rushing” to build more coal-fired power plants to drive economic growth before the “direction of wind” changes again to favouring emissions reduction. (Read more of Yu’s insight into China’s “coal push” in this Carbon Brief analysis.)

Dr Guo says the negotiation and bargaining between provincial governments and the central government is also why, most of the time, the pledges made by the latter are “very vague” because it is often unsure to what degrees the provincial governments can fulfil them.

Discussions of sub-targets and detailed timelines of national goals – such as peaking carbon emissions “before 2030” and achieving carbon neutrality “before 2060” – are often the results of a “consensus-forming” process between the central government and the provincial governments after those national goals were announced.

“That is when all levels of government carry out negotiation and bargaining,” Guo notes.

Lastly, apart from devising policies and collecting tax revenues, both the central and provincial governments run large companies known as state-owned enterprises (SOEs).

There are nearly 100 central-level SOEs, which include super-size firms, such as the State Grid and CHN Energy. They are operated by the State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission of the State Council.

Similarly, provincial SOEs, such as the Bensteel Group of Liaoning or the Zhejiang Provincial Energy Group, are operated by the state-owned assets supervision and administration commission of their respective provincial governments. Many provincial SOEs are drivers of the local economy.

Yu says that China’s SEO system is “unique” and “little known or understood by the outside world”, adding that the relationship between central-level SOEs and provincial SOEs mirrors that of the central government and provincial governments.

She notes that central-level SOEs are “more sensitive” to policies issued by the central government and, therefore, can implement them better.

Yu uses her preliminary analysis for Inner Mongolia as an example. She says that, among all the operating coal-fired power plants in the province, the installed capacity run by central-level SOEs is twice the amount run by the provincial SOEs. However, among the newly proposed coal power plants in the province, the proportion of the installed capacity run by central-level SOEs and provincial SOEs is “nearly the same”. Yu explains:

“This means that the coal-control and emission-control policies issued by the central government have more restrictions and direct impact on the central-level SOEs, whose portion of investment in coal power projects is decreasing [in Inner Mongolia].

“However, provincial SEOs are situated at the far side of policies and are responsible for delivering political performances for the provinces. Therefore, their passion [for coal] has not waned.”

A report published by Greenpeace East Asia’s Beijing office in July also highlighted provincial SOEs’ role in “China’s runaway coal expansion”. The research described provincial SOEs as “particularly responsive to short-term trends in energy planning”, in reference to a “rebound” of plans for new coal-fired power plants from late 2021 through to early 2022 – following the government’s order to ensure energy security.

In particular, the report said that the percentage of coal plants approved by provincial SOEs – as compared to central-level SOEs and non-state run enterprises – “decreased from nearly 60% in 2020 to 6.5% in the first three quarters of 2021, and back to 50% across Q4 2021 and Q1 2022”.

Lauri Myllyvirta – lead analyst at Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air – tells Carbon Brief that provinces and SOEs are the “main implementing bodies” for China’s “dual-carbon” policies. He says:

“I think one really important thing is for all the different provinces to identify something that they can do and some roles they can play in the new zero-carbon energy system.

“That should really be the role of their provincial CO2-peaking action plans. I [hope] that when that process is being set up, it will certainly contain much clearer plans for different provinces for the next 10-15 years.”

How can provinces affect energy transition?

There are two other secondary factors that are worth highlighting in showing provinces’ role in China’s climate change efforts: the development process of coal-fired power plants and the setup of the country’s power grid. Both can affect China’s energy transition progress.

Currently, in China, applications for new coal-fired power plants are verified and approved by provincial governments, not the central government, after the latter delegated its power to the former in 2014. (The move led to three times the average number of projects being greenlit by provincial governments the following year, Yu Aiqun says.)

An unwritten rule is that, although provincial governments are the ones to put a stamp on the construction permits for new coal power projects, they must get unofficial go-aheads from the central government for their decisions, according to Yu. She adds:

“Coal power has a closer relationship with the local economy, therefore, provincies are more motivated [to develop coal power plants].”

Yu says that not only are coal-rich provinces building new coal power plants, provinces “far away” from coal-producing regions – such as Hunan, Hubei and Jiangxi – are also building “large-scale” coal power projects.

According to Yu, the lower-income western province of Guizhou – which is known for having hydro power, as well as coal power using a more polluting type of coal, known as brown coal or lignite – has planned the most coal-fired power projects in the country in its provincial 14FYP, to drive its economy.

This sense of “strong impulse” towards coal power also means that as soon as the provincial governments detect a “change of direction” in the national policy on coal, they would rush to approve coal power projects before the floodgates close again, Yu notes.

For example, during the first six weeks of 2022, five new coal power projects with a combined capacity of 7.3 gigawatts (GW) were approved due to “shifting political signals”, according to a briefing jointly published by the CREA and GEM.

Among these five projects, two are situated in Zhejiang province on the east coast, one is in Hunan in southern China and the other two are located in Guangxi, which borders Vietnam. None of them is a traditional energy-producing province.

Throughout the first quarter of this year, “provincial governments across China approved plans to add a total 8.6GW of new coal power plants”, Greenpeace East Asia’s July report said, adding that the quarterly volume is “already 46.5% the capacity approved throughout 2021”.

(While provincial governments have been approving new coal plants, the power companies themselves have been more reluctant to actually build new capacity. Adding new plants erodes the earnings of existing units, which are already unprofitable.)

As for coal mines, the control from the central government to local governments are “very weak”, Yu adds.

She explains that, even though the right to approve new coal mines has always been in the hands of the NEA, the state energy regulator, the development of new coal mines “has never stopped” locally – even between 2016 and 2019 when the NEA banned the approval of new mines “in principle”.

As a result, in 2019, the NEA had to grant permits retrospectively to nearly 40 coal mines, with a combined capacity of 195m tonnes per annum (Mtpa), Yu notes. These mines had entered construction “illegally” during the previous three years when no permit had been issued, she adds.

In terms of China’s power grid, China has two state-run grids: China Southern Grid – which covers the five provinces in southern China – and the State Grid – which covers the rest of the country and comprises several sub-grids.

However, in reality, every Chinese province “pretty much” operates as its own power grid, Lauri Myllyvirta of CREA points out.

He says this situation creates a “challenge” because it leads to a “perceived need for a lot more coal-fired power” and makes it harder for renewable energy, especially wind and solar power, to be integrated into the grids.

Myllyvirta explains that, according to China’s plan for “clean energy bases”, provinces in eastern China are supposed to import “a lot of” renewable power from western provinces to reach the national target of having 50% of the power coming from the west to the east being “clean”. (Read analysis by Myllyvirta and his CREA colleague Zhang Xing on the “gigantic” wind and solar bases in west China.)

He notes that, to achieve this, eastern provinces will “really have to” adapt the way they operate their power grids – so they can reduce their local production to make space for renewable power when there is plenty of wind and solar generation in the west.

But “those provinces do not really like that because it reduces the operating hours of their local capacity”, he says, adding that, in general, provinces prefer generating their own power rather than importing it from other provinces because power generation can contribute to the provincial GDP and tax revenues.

Besides financial incentives, there are two other reasons behind China’s province-centric power grids, according to Myllyvirta. One is the “rigid management” that is not led by market needs. The other is the economic mindset of “mercantilism”, which means that Chinese provinces prefer generating their own power to importing it from other provinces.

Speaking about the role provinces play in China’s climate change actions, Myllyvirta says that provinces control or direct “so much” of the investment in infrastructure, housing, energy and industry, and, therefore, have the power to “shift the mix of investment between non-fossil and fossil energy. He tells Carbon Brief:

“When [China’s climate envoy] Xie Zhenhua talks about the idea that it takes some time for a big ship to turn, I really think that the challenge of aligning the interests and incentives for provinces with the carbon goals is the main piece of that puzzle.”

-

Explainer: Why China’s provinces are so important for action on climate change