Explainer: How hotter oceans can fuel more intense Atlantic hurricanes

Ayesha Tandon

10.09.24Ayesha Tandon

09.10.2024 | 5:45pmRecord-breaking sea temperatures across the Gulf of Mexico have been a key ingredient behind some of the intense hurricanes devastating the region this year.

Last month, Hurricane Helene made landfall on Florida’s “Big Bend” and then stalled over several states to the north dumping “enormous rainfall totals”, resulting in epic flooding which killed at least 220 people.

Just a couple of weeks later, Milton – the ninth hurricane to form in the Atlantic this year and one of the most rapidly intensifying hurricanes on record – has swept this week towards Florida’s Tampa Bay region, threatening communities that are still recovering from Helene’s impact.

A rapid attribution study recently concluded that record-breaking ocean temperatures in the Gulf of Mexico, which helped Hurricane Helene to “spin up”, were made 200-500 times more likely because of human-caused climate change.

Scientists tell Carbon Brief that the same intense ocean heat likely helped to fuel Milton’s behaviour and explains how hurricanes can become more intense in a fast warming world.

How do hot oceans fuel hurricanes?

A hurricane is the name for a tropical cyclone that forms in the Atlantic Ocean or northeastern Pacific Ocean.

Atlantic hurricanes typically first form over the tropical waters of the north Atlantic off the African continent. As the systems travel westwards across the Atlantic, they draw up the warm, moist air that rises from the surface of the ocean, using it to fuel themselves and grow stronger.

As the low-pressure system picks up energy, winds can begin to spin, forming a storm. The warmer the ocean water is, the more energy the storm accumulates and the more quickly it can intensify. Sea surface temperatures of more than 26.5C down to a depth of 50 metres can drive the storm to intensify into a hurricane, once wind speeds exceed 74 miles per hour.

The 2024 Atlantic season runs from the start of June to the end of November and has already seen multiple intense storms, including the powerful Helene and Milton hurricanes, which have struck Florida within just two weeks of each other.

Both hurricanes picked up energy as they travelled over the Gulf of Mexico, which is currently experiencing a marine heatwave.

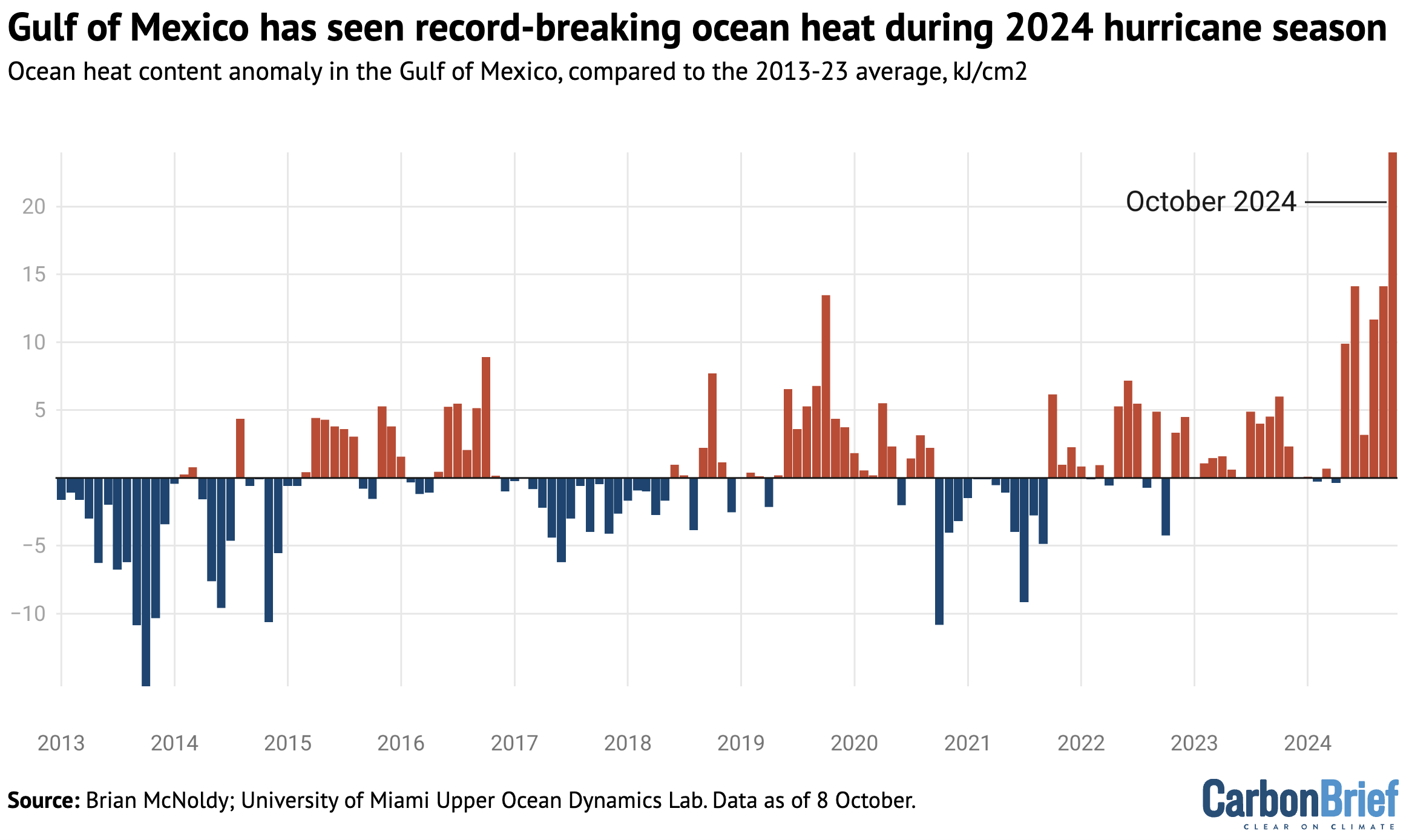

The graph below shows the extra ocean heat content – a metric that captures the amount of thermal energy stored in the water – for the Gulf of Mexico. For each month, it shows the extra ocean heat, compared with the average amount for that month during 2013-23.

A tropical storm is said to undergo “rapid intensification” if its wind speed increases by at least 35mph over a 24-hour period. Hurricane Milton’s wind speed accelerated faster than all but two previously recorded storms, with more than a 90mph increase in speeds in just 24 hours, ranking it as one of the “strongest” Atlantic storms ever recorded.

A study published in August in the Nature journal Communications Earth & Environment examined hurricanes that form over the Gulf of Mexico. It found that “rapid intensification” is 50% more likely to occur during marine heatwaves.

A rapid attribution study by Climate Central indicates that, over the past two weeks, the record-breaking temperatures in the Gulf of Mexico were made 400-800 times more likely by climate change.

Dr Kevin Reed – a researcher from Stony Brook University in New York – tells Carbon Brief that “Hurricane Milton’s rapid intensification this week is a telltale sign of climate change, which is responsible – in part – for the near-record temperatures in the Gulf of Mexico currently”. He adds:

“Warmer ocean temperatures are leading to more storms that undergo rapid intensification leading to an increase in the proportion of storms that reach major hurricane strength.”

A rapid attribution study from the World Weather Attribution (WWA) service examining Hurricane Helene used a model to investigate its strong winds by analysing storms making landfall within two degrees (120 nautical miles) of Helene. It said:

“By statistically modelling storms in a 1.3C cooler climate, this model showed that climate change was responsible for an increase of about 150% in the number of such storms (now once every 53 years on average, up from every 130 years) and, equivalently, that the maximum wind speeds of similar storms are now about 6.1 m/s (around 11%) more intense.”

“This is in line with other scientific findings that Atlantic tropical cyclones are becoming wetter under climate change and undergoing more rapid intensification,” the study finds.

A separate rapid analysis from the WWA team, published on Friday 11 October, finds that climate change increased rainfall from Hurricane Milton about 20-30% and made its wind speeds around 10% stronger. “In practice, this means that without climate change Hurricane Milton would have been a Category 2 rather than a Category 3 hurricane when it made landfall,” the study says.

Dr Kerry Emanuel, a professor of meteorology at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, tells Carbon Brief that “Milton’s behaviour is consistent with predictions that hurricane scientists have made going back at least three decades”.

New normal?

Since 1878, around six to seven hurricanes, on average, have formed in the North Atlantic every year, with only a couple typically making landfall in the US.

The number of Atlantic hurricanes on record has increased over the period 1851-2019. However, some research suggests that more consistent monitoring, rather than a true increase in hurricane numbers, is behind this trend.

There is a clearer trend of increasing hurricane intensity. Research shows that the proportion of tropical cyclones reaching at least category 3 intensity has also risen over the past four decades. Although the study does not confidently link this increase to climate change, it notes that higher sea surface temperatures are likely to contribute.

As Prof Andrew Dessler summarises on his Climate Brink blog, the impact of climate change on the intensity and frequency of tropical cyclones is still not certain. However, he says that “we can have high confidence that climate change will drive more intense hurricanes”.

Meanwhile, studies have shown that the record-breaking 2020 Atlantic hurricane season, when 14 hurricanes were recorded, was partly due to increased sea surface temperatures.

A study published by Nature Communications in 2022 found that human-caused climate change increased sea surface temperatures in the North Atlantic basin by 0.4-0.9C. The authors estimated that this increased “extreme three-hourly storm rainfall rates” and “extreme three-day accumulated rainfall amounts” for Atlantic storms by 11% and 8%, respectively.

Another 2022 study published in Nature Communications found that over the period 1982-2020, climate change-induced increases in sea surface temperatures doubled the probability of “extremely active tropical cyclone seasons”. The 2020 season might have been made twice as likely by ocean surface warming, the authors found.