Explainer: How ending gender violence will help deliver conservation goals

Yanine Quiroz

06.21.23Yanine Quiroz

21.06.2023 | 1:32pmWomen play a critical role in biodiversity conservation.

Globally, their contributions range from agricultural labour and working on nature reserves through to running environmental organisations and crafting international policies.

However, women who are dedicated to protecting biodiversity face violence.

According to a 2020 report from the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN), which surveyed more than 300 men and women who worked in sectors with close ties to conservation, 59% of the women respondents had observed some form of violence while carrying out environmental projects.

Gender-based violence can take many forms, ranging from psychological violence, including discrimination, through to physical, sexual and economic violence. It can even lead to murder.

The World Health Organization describes violence against women as a “major human-rights violation”. But, according to the IUCN report, it could also jeopardise the world’s ability to achieve biodiversity targets pledged in international agreements.

One such agreement is the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework, a landmark deal agreed upon by nearly 200 countries last year in order to “halt and reverse” biodiversity loss by 2030. It contains two targets to ensure gender equality and a “gender plan of action” that seeks to “prevent” and “eliminate” gender-based violence in biodiversity conservation.

This means “parties have agreed at the global level that this is a real issue,” Jamie Wen-Besson, a senior gender programme manager at IUCN, tells Carbon Brief.

In this explainer, Carbon Brief lays out how gender-based violence impacts women in biodiversity conservation – illustrated with examples from the global south.

It also highlights some of the solutions that exist. These range from empowering women with courses on vehicle maintenance for travelling alone in the field through to amending non-governmental organisations’ constitutions to include women in senior positions.

Women in biodiversity

Biodiversity is essential for human well-being and the health of the planet.

Today, around a million species are facing extinction, according to the latest global assessment report by the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES).

Climate change is one of the main drivers of biodiversity loss. One in 10 species worldwide may be at very high risk of extinction on a planet with 2C of warming, according to the 2022 report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) on impacts, adaptation and vulnerability to climate change. (For more on the links between climate change and biodiversity loss, see Carbon Brief’s explainer.)

In addition, women, Indigenous peoples, the elderly and children are some of the most vulnerable populations to climate change.

Extreme events, such as drought, floods, hurricanes and sea-level rise, are “felt more keenly by women than men as a result of systemic gender discrimination and societal expectations related to gender roles”, found a 2022 report from the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC).

Such climate-induced events disproportionately affect women’s health, according to the IPCC. Women experience more significant mental health burdens, food insecurity and complications during pregnancy associated with vulnerability to heat, air pollution and infectious diseases.

A 2022 study found that extreme events, such as floods, heatwaves and wildfires – and the economic shock, social instability and stress that follow such events – increase gender-based violence against women.

The IPBES report says that in order to overcome these challenges, conservation needs to be inclusive and consider the needs of local communities, Indigenous peoples, women and girls.

Unique role

Women carry out a range of important activities in biodiversity and ecosystem conservation, from collecting non-timber forest products, such as seeds, to preventing deforestation and managing water for their families, according to a 2017 study.

But the scope is broader than that, says Cate Owren, senior advisor on gender equality at the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). She explains to Carbon Brief that women are stewards, natural-resource managers, educators, caregivers, defenders of their resources and territories, and farmers who contribute to feeding their families and communities.

Indigenous women, in particular, have a strong connection with nature, due to their reliance on plants for healing and on other forest products to feed their families, says Sara Omi, an Indigenous leader from Panama.

Omi is the president of the Coordinator of Territorial Women Leaders of Mesoamerica, a platform for dialogue and advocacy that brings together women from countries ranging from Panama to Mexico. The group is composed of 13 women’s organisations that make up the Mesoamerican Alliance of Peoples and Forests. Omi tells Carbon Brief:

“We are the guardians, protectors, [we are] knowledgeable of everything within our environment…We transfer knowledge across generations.”

She adds that Indigenous women will “always be there for the care of mother Earth”.

Owren points out that women’s contributions to biodiversity vary across regions due to cultural, geography and ecosystem distinctions. She tells Carbon Brief:

“Women in mountain zones may be doing their roles and responsibilities differently from a woman in the Amazon.”

Globally, women account for 38% of agrifood systems workers – those linked to the production of food and non-food agricultural products from agriculture, livestock, fisheries and aquaculture. However, they do so earning 82 cents for every dollar men earn.

Yet the total global contribution of women across environmental sectors has yet to be quantified.

A 2021 report published by Women4Biodiversity – a collective of women and civil-society groups that advocates for empowering women under international conventions – says that women in these fields “are still invisible and, in most cases, unaccounted for”, which hinders the recognition of their unique roles and the establishment of more gender-responsive policies.

Along with the information gap regarding women’s roles in biodiversity, women are also often relegated to secondary roles and have low participation in decision-making, the report points out.

That is due to roles women and men have been assigned to manage natural resources, says Owren. She adds that these roles are defined according to socially constructed gender norms. Men often have higher incomes from jobs and land profits, while women may be relegated to domestic work and fetching water – and are typically restricted from paid jobs or from doing fieldwork.

One group that is pushing back against these traditional roles is the Black Mambas in South Africa. They are the first all-female anti-poaching unit, aimed at protecting rhinos and elephants without using guns, bullets or violence. They patrol sections of the Greater Kruger Area, located in north-east South Africa, which is home to the largest population of rhinos in the world.

As part of the group, 24 women work in the field, patrolling the borders of protected areas and preventing poachers from coming into the reserves. Another five members of the group stay in the village, where they teach the importance of conserving rhinos, both for the community and the planet. The Black Mambas have helped reduce poaching by 63% since their formation.

“Our aim is to make Balule [a nature reserve inside the Greater Kruger area] a hard place for poachers,” says Leitah Mkhabela, the Black Mambas supervisor. She tells Carbon Brief that the group abstains from violence because they “don’t want to live in a world where there are widows and orphans”. She adds:

“That’s why the Black Mambas are unarmed – because we cherish life.”

The Black Mambas have elevated women’s voices in the community and inspired other women outside South Africa, such as in Zimbabwe, Mkhabela says. She adds that “we need more women [to get] into nature conservation” because they can be rangers, stop poaching and protect animals through a more pacific perspective that cares about nature and people.

The different faces of violence

The UN Refugee Agency defines gender-based violence as “harmful acts directed at an individual based on their gender”. The organisation says that such violence “is rooted in gender inequality, the abuse of power and harmful norms”.

The World Health Organization recognises it as a “major human-rights violation and a global public-health problem”. It also points out that women at higher risk of violence are migrants, Indigenous, transgender women and those with disabilities.

Specifically, violence against women dedicated to biodiversity conservation is underreported, says Owren. Before joining UNDP, Owren contributed to a joint report produced by the IUCN and the US Agency for International Development (USAID) on the links between gender-based violence and biodiversity.

When the IUCN started researching for the report, it knew gender-based violence was occurring, Owren says. Still, there was a gap between the biodiversity and climate change sectors regarding the handling of gender-based violence – so the authors of the report decided to build the evidence to support such policies, she adds.

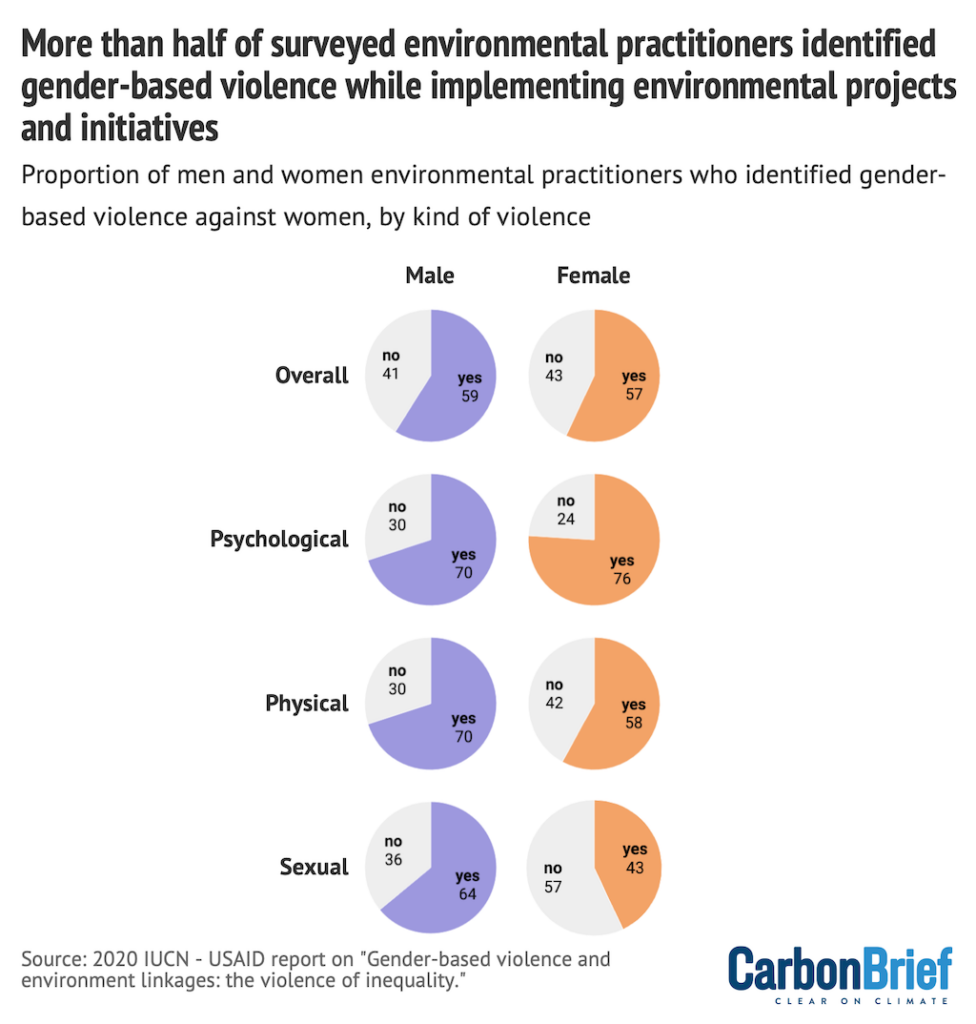

The IUCN report surveyed 303 practitioners working in gender or environment sectors. Of the respondents, 69% were women and 31% were men.

The results show that 59% of women and 57% of men who responded to the survey had observed – although not necessarily directly experienced – cases of gender-based violence while implementing environmental projects and initiatives.

Psychological, physical and sexual violence against women were the forms of violence most-often reported in the survey.

Of the survey respondents who said they had observed violence, 76% of women and 70% of men reported observing psychological violence. At the same time, physical violence was reported by 58% of female respondents and 70% of male respondents. Sexual violence was observed by 43% of women and 64% of men, and sexual harassment was reported by 40% of women and 55% of men.

However, the IUCN survey only reflected the perception of environmental practitioners – it did not fully capture the experiences of all women that work for the environment and have suffered from violence, says Laura Sabater, a gender programme officer at IUCN, who was also a co-author of the report. But, she adds, it reveals how changes in power dynamics can lead to different types of violence.

The report concludes that gender-based violence “is used to assert control over natural resources and to diminish the efforts of those working towards a safe and healthy environment”.

Several factors contribute to gender violence, from discriminatory gender norms – such as abuse of power or discrimination in the workplace through lower wages than men – to a lack of consequences for the perpetrators.

The IUCN report also illustrates how different forms of gender-based violence overlap. Owren tells Carbon Brief:

“Women’s land titles being taken away is a form of economic violence, but [when] done through physical, emotional, psychological or sexual violence, it’s horrifying.”

Omi experienced something similar. She is an Indigenous leader among the Emberá people in Panama and was the first woman to become a lawyer in her territory.

Emberá women face discrimination and violence when they want to participate in politics and decision-making, Omi says. Men will attack women for participating and question whether they are fit to hold important office. “Men will ask: ‘why is this woman here?’,” Omi says.

From 2016 to 2021, Omi was the traditional authority from the Emberá General Congress of Alto Bayano in Panama, where she participated in the governance of the Emberá territory. She also helped defend her community’s rights to their land and natural resources, and stayed on the lookout for better social, political and economic opportunities for the Emberá people.

After that period, Omi ran for a crucial role: congressional chieftain, the highest authority of the Emberá Congress. The chieftain coordinates the governing body and the consultation process of the community.

But, before the elections, she was accused of financial corruption – even though, she says, the Congress government does not manage funds – and lost the vote. A man was elected instead, amid allegations of fraud, and the older men in the territory looked for ways to prevent Omi from running for office again, she says.

The man was ultimately ratified as the new congressional chieftain. He maintained that “the elections [that were] carried out fully complied with all the requirements of the election regulations approved by the General Congress”, the Panamanian outlet La Estrella de Panamá reported at the time.

Omi sued the election process in the Ombudsman’s Office of the Republic of Panama, which issued a statement at the national level that recommended that these elections be held again because they had found elements of fraud. However, it “unfortunately was not fulfilled”, she says.

At that time, the Ombudsman’s Office met with the elected man. He and the members of the Emberá Congress described the meeting with the ombudsman as “historic”. The ombudsman was also “invited to visit the region to learn about the needs of the Indigenous people”.

Omi was attacked both psychologically and over social media during that period. She tells Carbon Brief that the experience “has been so painful”, but she is now managing to deal with that ordeal. She uses her experiences to continue protecting the Emberá territory and fighting to empower women in the community.

A global issue

A lack of research on the subject means that the distribution of cases of gender-based violence globally is unknown. But some groups, including the campaign group Global Witness, are trying to provide some insight.

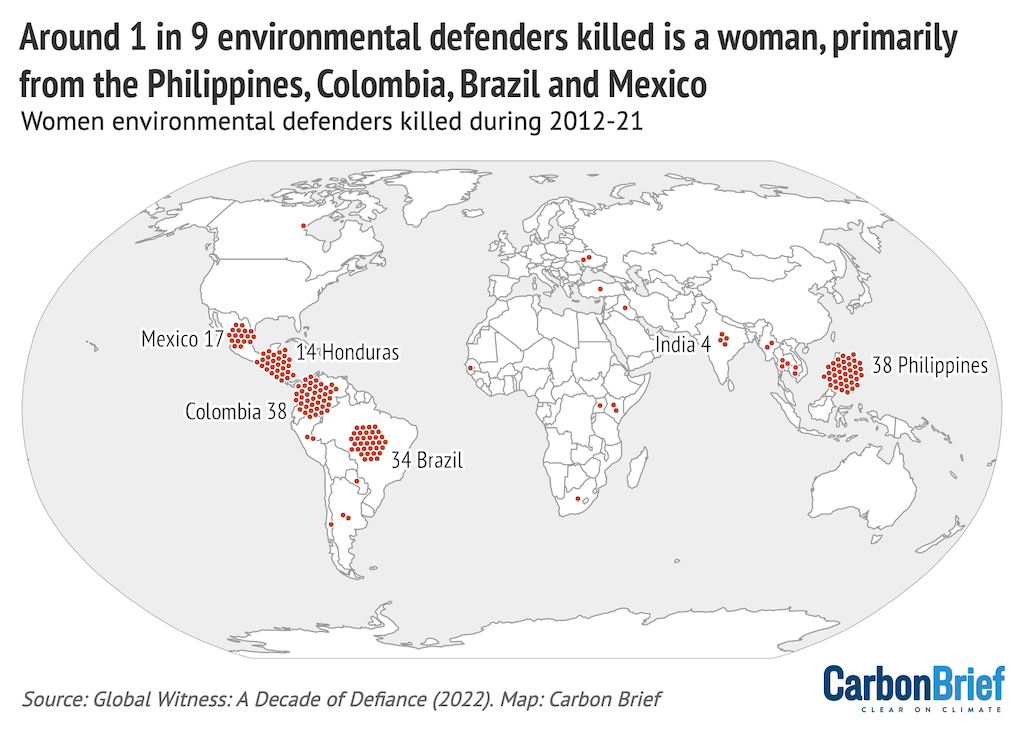

Between 2012 and 2021, an estimated 1,733 land and environmental defenders were killed for “trying to protect their land and resources”, according to a 2022 report from the group. Of these, 183 were women.

The report stresses that this data is just the tip of the iceberg, due to limitations on press freedom and a lack of independent and verified recording of attacks. It says:

“Beyond killings, many defenders and communities are also being silenced through the use of tactics such as death threats, surveillance, sexual violence or criminalisation. These types of attacks are even more underreported.”

The map below shows the countries where the 183 female land and environmental defenders were killed during 2012-21. The murders were registered primarily in Asia and Latin America.

The report also links murders against women environmental defenders to different industries, where possible. It found that the most deaths were associated with mining and extractive industries (39 deaths), agribusiness (14), hydropower (14) and logging (12).

A recent study in Nature Sustainability explores some of the other consequences that extractive industries pose on women environmental defenders. It examines 523 cases of violence against women environmental defenders; in 81 of those, women were “assassinated for their advocacy”, the study finds.

It also addressed other forms of violence women defenders deal with, such as criminal prosecutions, displacement from their homes and abuses of their human rights.

“Repression, criminalisation and violent targeting are closely linked, while displacement and assassination appear as extreme outcomes when conflict violence worsens,” the study says.

The 2020 IUCN gender report also highlights other kinds of gender-based violence.

One example is the sex-for-fish practice, which is common in eastern and southern Africa.

The practice consists of female fish buyers being exploited by male fishermen, who demand sex in exchange for their catch. The practice, which hinges on unequal power dynamics and generally occurs in small fisheries, leaves the women more vulnerable to HIV and Aids, according to the IUCN report.

Kenya developed the “no sex for fish” project to help end this practice. The project established a women’s cooperative to enhance their business skills and facilitate financial support through savings and loans. The cooperative helped women to own their own boats: in six months, three boats were built, helping women run successful businesses.

Although the programme did not end the practice of exchanging fish for sex, it brought cultural changes by raising awareness about these harmful activities, according to the report.

Another example is child marriage, which is typically practised in parts of south Asia, where 56% of women are married before 18, and sub-Saharan Africa, where it is 46% of women. Niger, in north-west Africa, has the largest prevalence of child marriage: 77% of women there are married before 18, compared to 5% of men, according to the IUCN report. In Bangladesh, the report says, child marriage has been a survival option for women living in places threatened by disasters.

“Child marriage, however, is not only a violation of children’s rights – it has a ripple effect at every stage of their lives” and perpetuates violence, says the report.

Discrimination, abuse of power and harassment at workplaces are other kinds of gender-based violence that affect women in different regions, the report finds.

In Argentina, for example, a woman in the fire brigade was removed from fieldwork because of her gender.

Larissa Gómez, a Mexican forest engineer, experienced a similar situation. In 2019, she went to the Lacandon Jungle in southern Mexico, accompanied by her husband, to investigate how carnivores, such as jaguars and cougars, eat livestock.

When she was interviewing livestock farmers, the men only looked at and spoke to her husband, even though she was the one conducting the research. She tells Carbon Brief:

“It was quite uncomfortable and I was afraid to walk alone. I wouldn’t have had to be accompanied if I were a man, but that’s the situation in our country.”

She also experienced harassment during her academic studies, she says.

Empowerment

In response to the violence suffered by women working in biodiversity conservation, several initiatives have been created by civil-society organisations to promote gender equality in conservation projects and empower women in environmental work.

Tatiana Galluppi is the director of the Paraguayan Organization for Conservation and Sustainable Development (OPADES), a non-governmental organisation that performs conservation in protected areas, biodiversity monitoring, research, community science and environmental education for children across the country.

Since 2015, Galluppi and her team, which is composed of a technical team and a network of more than 200 young volunteers, have been working with local communities.

OPADES promotes the empowerment of young people and women, Galluppi says. Staff and volunteers receive training to understand how to prevent violence among all the members of the organisation and ensure gender equality in the activities they carry out. The group includes a mechanism to make complaints from members, volunteers or external people. They also held two workshops last year on gender-based violence.

Galluppi tells Carbon Brief:

“We seek to strengthen and take the issue of safe environments seriously because we know that in conservation, it is quite difficult to arrive in rural areas where machismo is deeply rooted.”

She is also planning to create workshops on vehicle maintenance and repairs for women in OPADES. She says this will make them more independent when travelling alone into the field, so they will be able to undertake conservation projects without needing to be accompanied by a man.

Her commitment to amplifying gender equality in her organisation came after having experienced gender-based violence herself. In the middle of a fieldwork in Paraguay, she was harassed by a coworker.

She sued her harasser, but some colleagues denied her version of events. However, thanks to the lawsuit, more women raised their voices about having similar experiences, and the man was dismissed. She says:

“I want every woman to know that we are not alone. The most important thing is to be united.”

Solidarity between women is one of the many solutions to reach gender equality in biodiversity conservation.

Gemara Gifford, a PhD student of socio-environmental sciences at Colorado State University who has worked in Central American communities, says that the first step to mitigating gender-based violence is trying to heal.

She describes how she worked on a project in Guatemala – led by organisations such as Trees, Water and People, Utz Che’ Guatemalan Community Forestry Association and USAID – where they created “collective healing spaces” to heal both individually and as a group of women. In those spaces, women gather to identify the violence and help each other process the violence they have suffered.

At the community level, organisations can combat gender-based violence by, for example, educating men to recognise the rights of both Indigenous and community women, says Omi.

The IUCN report provides successful cases of such education. In one of their projects in Rwanda, ActionAid – an international non-governmental organisation that works to end poverty and injustice – found that women noted “changes in men’s behaviours towards women’s engagement in cooperatives” after implementing trainings aimed at sensitising men to gender issues.

Owren tells Carbon Brief:

“It’s not just the work of women. Ending gender-based violence requires [new] social norms. And that means we need different players at the table to change the culture. [That] takes time.”

International response

Since the UN established the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) in 1979, women’s rights and the eradication of violence against women have been widely recognised in international policy as important requirements for conserving the environment.

One of the most-cited international agreements that protects women’s rights is the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. It was adopted in 2007 and aims to protect Indigenous women and children from all forms of violence.

International treaties such as the Convention on Biological Diversity have specifically acknowledged the crucial role of women in biodiversity conservation and the need for their participation in policy-making.

In 2022, the UN biodiversity summit COP15 in Montreal saw the emergence of the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework. The framework contains 23 targets. Two of them – targets 22 and 23 – are related to gender equality.

Target 22 aims to protect environmental human-rights defenders and ensure the inclusive representation, participation and access to justice and information by women, Indigenous peoples and youth.

Target 23 calls for recognising access to land and natural resources, participation and leadership of women and accomplishing a gender-responsive approach in implementing the framework.

Including the term “gender responsiveness” enshrines the security and safety of women environmental defenders in the framework, says Wen-Besson.

Furthermore, there is “growing evidence” that reaching gender equality can bring “positive outcomes for both nature and community well-being”, wrote two scientists in a perspective piece published in Nature calling on decision-makers to implement such targets.

In addition to the framework itself, the accompanying “gender plan of action” – a strategic document to support the gender-responsive application of the framework – includes an objective on gender-based violence (objective 1.5). It reads:

Wen-Besson tells Carbon Brief that this “means parties have agreed at the global level that this is a real issue”, but adds that combating gender-based violence “needs action, research and solutions”.

Nearly 30 countries mentioned gender inclusion in their climate pledges under the Paris Agreement, with two countries referring to the term “gender-based violence”, according to an IUCN analysis. Wen-Besson says:

“The fact that there’s recognition [of gender inclusion] in national policies of 28 countries, it’s significant.”

In order to work towards ending gender-based violence, environmental organisations can develop analyses to identify and address gender-based violence, partner with humanitarian and health organisations to prevent violence and prioritise evidence-based projects to get financing from public and private funders, according to the IUCN.

International organisations and research centres can also contribute to this analysis. A recent perspective article in Nature Food calls for a collective agenda to research gender-based violence in food systems and for its inclusion in international reports and policies.

Most women interviewed for this article mentioned that access to funds and capacity building was essential to achieve gender equality.

Some funding mechanisms that support gender equality in environmental programs exist already. The Global Environment Facility and the Green Climate Fund both include requirements to make sure projects do not exacerbate or create gender-based violence.

The IUCN Resilient, Inclusive and Sustainable Environments (RISE) grants have financed nine projects across Africa, Asia and Latin America for addressing gender-based violence in environmental projects, reaching over 11,500 beneficiaries.

One of those grants was to the Kenya Wildlife Conservancies Association (KWCA), an umbrella organisation representing 167 conservancies in Kenya.

The association trained its staff to enhance the discussion on power norms and gender-based violence. After the training, they observed positive attitudes among the KWCA staff towards implementing actions to increase gender equality during their operations, says Joyce Peshu, a gender officer at the organisation. For example, she points out that KWCA amended its constitution to ensure that their national conservancy council includes women in the election.

Peshu tells Carbon Brief:

“One of the lessons that we [learned]…is looking at women’s economic empowerment. [That means] being able to support women already doing nature-based enterprises, to grow their businesses to a level that they gain confidence to abide opposition and get into leadership spaces in conservation and natural resource management.”

Some women that now hold strategic roles in biodiversity conservation have overcome episodes of gender-based violence and promoted women’s empowerment. Gifford says that while “some survivors become influential leaders later on”, this often does not occur until “after they’ve left their community or left that violence”.

However, women cannot be the only ones working to change this reality, says Wen-Besson. International and national support is essential to address gender equality in conservation globally. She tells Carbon Brief:

“As a survivor, I don’t want to say that the responsibility is on survivors and women. Solutions require every tool in our toolbox: capacity, people, knowledge, products, guidance, money, policies and institutional change.”

This article is also available in Spanish.

-

Explainer: How ending gender violence will help deliver conservation goals