Every five-year delay in meeting Paris goals could ‘add 20cm’ to global sea levels

Daisy Dunne

02.20.18Daisy Dunne

20.02.2018 | 4:00pmFailure to meet the goals of the Paris Agreement within the next few decades could have long-lasting impacts on global sea level rise in the coming centuries, new research finds.

A study finds that each five-year delay in meeting the goal of reaching global peak CO2 emissions could drive sea levels to rise by an additional 20cm by 2300.

This amount of sea level rise is roughly equal to what the world has experienced since the start of the industrial revolution more than 200 years ago, the lead author tells Carbon Brief.

The findings reiterate that “peaking global CO2 emissions as soon as possible is crucial for limiting the risks of sea level rise”, the author adds.

Race to zero

Samples taken from ice cores, tide gauges and satellites show that global sea levels have risen by around 19cm from pre-industrial times to present, with recent research showing that the rate is likely to be accelerating.

The new study, published in Nature Communications, estimates how delays in meeting the goals of the Paris Agreement could affect the total amount of sea level rise by 2300.

Under the Paris Agreement, countries have pledged to cut their rates of emissions in order to keep future global temperature rise “well below” 2C. To achieve this, nations agreed to reach “peak” CO2 emissions “as soon as possible”. This will be key to achieving “net-zero emissions” within the second half of this century.

The new research shows that the speed at which the world can cut its greenhouse gas emissions is becoming “the major leverage for future sea levels,” says study lead author Dr Matthias Mengel, a postdoctoral researcher from the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impacts (PIK) in Germany. He tells Carbon Brief:

“The way that emissions will evolve in the next decades will shape our coastlines in the centuries to come: five years of delayed [CO2] peaking will lead to 0.2 metres more sea level rise in 2300. This is the same amount we have experienced so far since the beginning of the fossil economy.”

Melting prospects

![]()

For the study, the researchers used climate models to simulate future sea level rise by 2300 under two future scenarios. Both of the scenarios assume that the world will meet the Paris goals by the end of century and use a low-emission pathway known as RCP2.6.

The first scenario, called “net-zero greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions”, assumes that future temperature rise will be limited to well below 2C and a balance between emissions and uptake of greenhouse gases is met by the end of the century.

The second scenario, called “net-zero CO2 emissions”, is a future in which temperatures are stabilised at levels well below 2C but GHG emissions are not balanced by the end of the century. This scenario results in more or less stable temperatures. However, the net-zero GHG scenarios result in a peak and decline of global temperatures, and thus allow for a potential temporary “overshoot” of the temperature targets, which some scientists suggest is likely.

The researchers used these scenarios to work out possible future global temperatures and applied them to a model of long-term sea level rise.

Global warming causes sea levels to rise in three main ways, Mengel says: “thermal expansion”, when seawater expands as the oceans absorb additional heat from the atmosphere; melting glaciers; and ice loss from the large ice sheets of Greenland and Antarctica.

The model incorporates recent research (pdf) finding that the Antarctic ice sheet may be more sensitive to climate change than previously thought, Mengel says:

“The contribution from Antarctica increases with warming, faster than all other components.”

Closing window

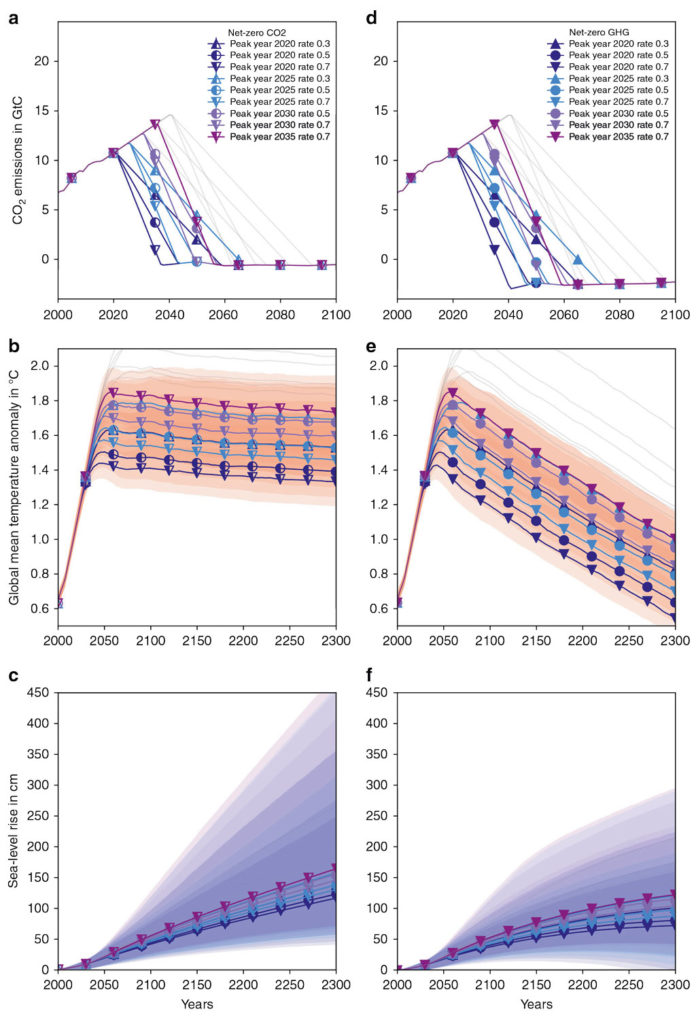

The charts below show the expected CO2 emissions, temperature rise and sea level rise for the net-zero CO2 emissions scenario (a-c) and the net-zero GHG emissions scenario (d-f).

On the charts, coloured lines and symbols are used to indicate the expected outcomes of reaching peak CO2 emissions in five-year intervals from 2020 to 2035. Scenarios that do not limit global warming to 2C are shown in thin grey lines.

Shading shows the 66th percentile range of each scenario in b and e and the 90th percentile range in c and f.

The charts show that, for every five-year delay in reaching peak emissions (upper charts), temperatures rise higher (middle charts), which causes more sea level rise in the long run (lower charts).

Expected CO2 emissions, temperature rise and sea level rise for a net-zero CO2 emissions scenario (a-c) and a net-zero GHG emissions scenario (d-f). Coloured lines and symbols are used to indicate simulations at five-year intervals from 2020 to 2035. Grey lines show simulations exceeding 2C. Shading shows the 66th percentile range of each scenario in b and e and the 90th percentile range in c and f. Source: Mengel et al. (2018)

The results suggest that sea levels could rise by 70-120cm by 2300 under a low emissions scenario. This level of sea rise could significantly increase the risk of flooding in coastal cities, such as New York, and island atoll nations. Currently, global emissions are tracking a higher scenario known as RCP8.5.

The results also indicate that, even once net-zero emissions are achieved and temperatures begin in fall, sea levels will continue to rise. This is because the drivers of sea level rise respond slowly to climate change, Mengel says:

“There are also unstable processes that, once triggered, will not stop contributing to sea level rise, independent of global mean temperature rise. An example of this could be the potential collapse of the West Antarctic ice sheet.”

Peak urgency

The findings show that the world must “reduce its emissions as fast as possible” in order to protect future generations from extreme sea level rise, Mengel says:

“Peaking global CO2 emissions as soon as possible is crucial for limiting the risks of sea level rise, even if global warming is limited to well below 2C.”

The results could hold relevance for today’s large infrastructure projects, which typically have a lifespan of more than 100 years, says Dr Natasha Barlow, a university research fellow specialising in sea level change from the University of Leeds, who was not involved in the research. She tells Carbon Brief:

“As a result, there is huge value in studies which consider the rate and magnitude of sea level rise beyond 2100. There are very few studies which do, largely as the uncertainties increase the further into the future we try to predict.”

However, the models used in the study do not include all of the “low probability, high risk” drivers that may contribute to sea level rise, she adds:

“There may be additional long term sea level rise from melting ice, above that predicted by the authors, due to marine ice-sheet instability driven by warmer ocean waters around West Antarctica and an albedo feedback over Greenland.”

Updated on February 21 to clarify the difference between the two scenarios used in the study.

Mengel, M. et al. (2018) Committed sea-level rise under the Paris Agreement and the legacy of delayed mitigation action, http://nature.com/articles/doi:10.1038/s41467-018-02985-8

-

Every five-year delay in meeting Paris goals could ‘add 20cm’ to global sea levels

-

"Peaking global CO2 emissions as soon as possible is crucial for limiting the risks of sea level rise”