EU energy package: What it means for coal, renewables and efficiency

Sophie Yeo

12.01.16Sophie Yeo

01.12.2016 | 4:28pmThe literature on EU energy regulations got longer by about a thousand pages yesterday, as the European Commission put forward its vision for achieving a “clean energy transition”.

The vast collection of documents — including revisions to directives, impact assessments, enquiries and new regulations — will determine the future of energy in the EU up to 2030. It touches upon subjects including coal subsidies, bioenergy, grid access and rights for individual energy producers.

Referred to as the EU’s “winter package”, the new rules will partly determine how successfully the EU meets its 2030 climate objectives, as well as setting out a common energy system for the EU’s 28 member states, known as the Energy Union.

Jonathan Gaventa, a director of the thinktank E3G, tells Carbon Brief:

“This is the main legislative vehicle for the energy side of the energy union. There have been a few pieces of legislation on climate and gas security, but the bulk of energy measures are essentially coming out at the same time, in one big go. And that [is] nearly all the legislation that gets published by the Commission.”

The proposed legislation will have to be approved by the European Parliament and the Council of Ministers before it becomes official, which means that it is unlikely to remain in its current form. The package will probably not be adopted before 2018/19, meaning it is unclear whether the UK will end up writing these rules into its own law, in light of the decision to leave the EU.

Priority dispatch

The EU package changes the rules on what types of energy should be given priority (“dispatched”) in the grid.

The decision about what sources of power are prioritised is based partly, but not only, upon the price of the electricity being produced, to ensure that consumers are getting the cheapest option on the market.

Renewables had a distinct advantage under the Renewable Energy Directive adopted in 2009, as they were given priority over fossil fuel generators, as a means of keeping carbon emissions low and ensuring a market for renewable power.

This advantage is revoked in the proposed legislation released this week. Now, with a few exceptions, renewable power will be treated in the same way as fossil fuel power when it comes to the order in which it is dispatched to the grid.

The exceptions include renewable energy installations with a capacity of less than 500kW (a threshold that shrinks to 250kW from 2026), demonstration projects for innovative technologies, and existing installations (unless they are modified or expanded).

The EU says that this will ensure a “level playing field for all technologies without jeopardising our climate and energy targets” — and, indeed, with low or non-existent cost of actually generating wind and solar power, renewable plants should end up dispatching to the grid first regardless of the legislation.

But NGOs are incensed about the change. According to an EU impact assessment seen by the Guardian, it could increase carbon emissions by up to 10%.

Jean-François Fauconnier, renewables policy coordinator at Climate Action Network Europe, said:

“The Commission deserves severe criticism for proposing to undermine market access for renewable energy. The proposals do not reflect the increasing economic benefits of renewable energy and citizens’ desire to participate in the market. The Commission chose to propose a very weak set of rules to appease backward looking member states, and harmful and outdated fossil fuel industries.”

There are concerns that abandoning the principle of priority dispatch could start to cause problems in times of overcapacity — if the grid is too congested, then the flexibility of renewables means that they could be the first to be curtailed.

Capacity mechanisms

Capacity mechanisms are a method of ensuring a constant supply of electricity, in an age when generation is becoming less predictable because of the higher penetration of renewables into the grid.

They typically offer payments to generators on top of the money they earn from selling their electricity in exchange for maintaining existing capacity.

Payments to keep coal capacity online can be seen as a subsidy for some of the polluting plants from which the EU is working to distance itself. Many European nations have chosen to implement them, but their methods so far lack uniformity.

“Like mushrooms, they just kind of spring up across Europe in an unpredictable fashion,” E3G’s Gaventa told Carbon Brief.

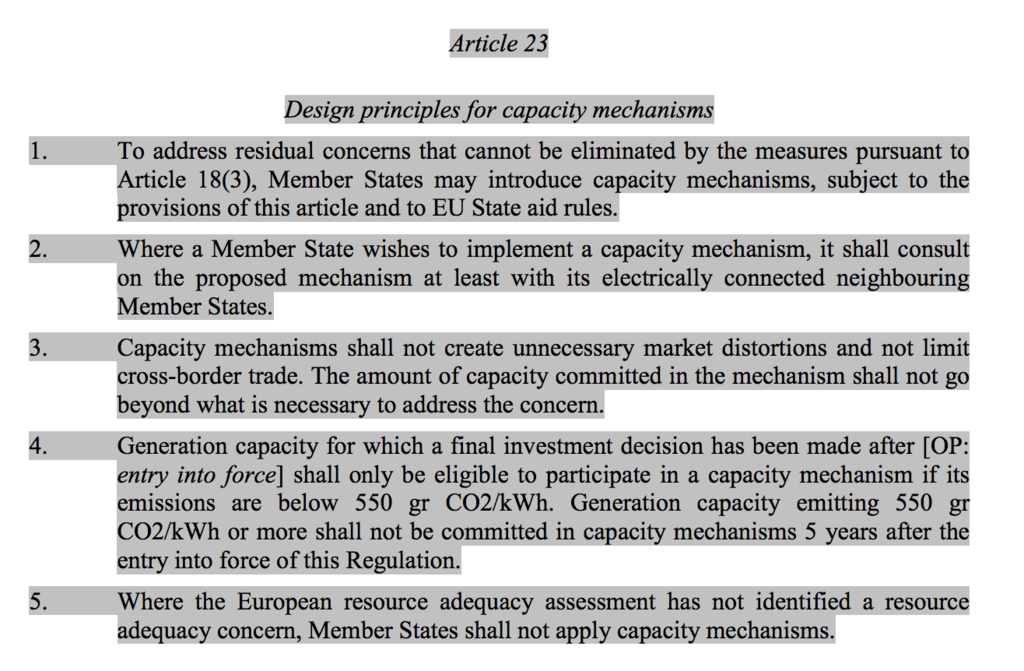

Extract of new EU regulations, setting out the new design for capacity mechanisms. Source: Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on the internal market for electricity

As part of its winter package, the EU has issued both the result of its enquiry into capacity mechanisms and a new set of design principles for countries that want to use them.

Under the new rules for capacity mechanisms, member states must consult on its proposed mechanism “at least with its electrically connected neighbouring member states”, the legislation says, adding that states may not add more capacity than is necessary to address their concerns over security of supply. This will help to create more coherence across the 28-state bloc.

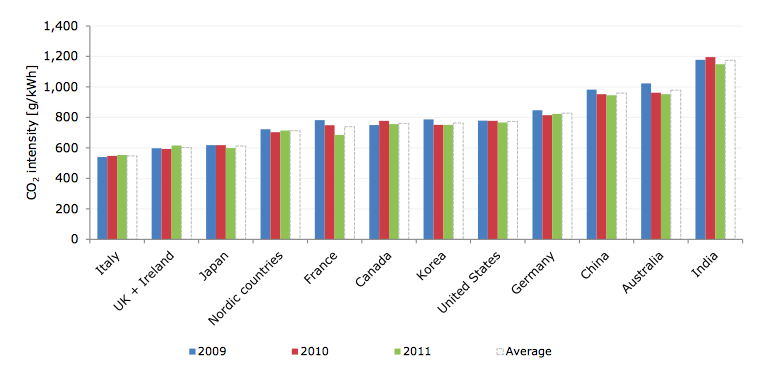

But, perhaps most importantly, the new rules impose an emissions limit on what can receive payments under capacity mechanisms. New capacity is only eligible if it emits less than 550 grams of CO2 per kilowatt hour (CO2/kWh), although existing plants are initially exempt from this rule. This all but rules out new coal plants from getting paid through capacity mechanisms.

CO2 intensity for fossil-fired power generation. Source: Ecofys

Five years after the regulation has entered into force, this limit applies to all plants given capacity payments.

Maroš Šefčovič, vice-president of the Commission and in charge of the Energy Union, highlighted the “high environmental standards” of the new capacity mechanism arrangements. However, NGOs pointed out that it left loopholes for subsidising existing coal plants.

“We are substantially restricting the use of capacity mechanisms by Member States, eg. applying high environmental standards” #CleanEnergyEU

— Maroš Šefčovič (@MarosSefcovic) November 30, 2016

According to Greenpeace, at least 95% of coal power plants would be eligible to receive capacity payments until 2026 under the Commission’s proposals.

Energy efficiency

The Energy Union operates under the principle of “energy efficiency first” — but the target has long been the subject of conflict. “The cheapest energy, the cleanest energy, the most secure energy is the energy that is not used at all,” says the proposal.

In 2014, the European Council agreed a 27% energy efficiency target by 2030, with a review before 2020. Today’s proposal increases this target to 30%.

The proposal says that member states should continue with the previous pathway of achieving the overall target through incremental improvements of 1.5% per year. This would be sufficient, the document says, to take the EU to — but not beyond — the 30% objective.

According to the impact assessment, the 30% target will lead to a €9bn increase in energy system costs compared to the 27% target. However, it’ll make this back in the long run, as the same amount would be saved as a result of the higher target between 2021 and 2050.

For many, the 30% target is still not enough. The European Parliament has called for 40% energy efficiency target by 2030, saying this this would result in net savings of €239bn per year on energy bills. Some businesses, including Philips Lighting and Siemens, have also called for a higher target.

The board of directors of the European Alliance to Save Energy expressed disappointment at the new target. It said:

“We have showcased energy efficiency as a success story,the business opportunity behind energy efficiency has been acknowledged, but by setting the target at 30%, the European Commission has fallen short from unleashing the full potential of energy efficiency and the related benefits to consumers. The proposed target will not sufficiently push the EU beyond business-as-usual, but will maintain the current speed and rate of investments.”

Bioenergy

Bioenergy is a complicated and heated subject within the EU. By 2020, bioenergy is expected to contribute 57% of the EU’s total renewable energy, but there are serious questions about whether this is a truly sustainable alternative to fossil fuels.

The revised legislation proposal introduces new sustainability criteria for bioenergy production, including new rules aimed at ensuring forests are harvested sustainably and conservation areas are protected. It also establishes new thresholds for the amount of greenhouse gas emissions that must be saved by switching to biofuels.

Here’s what EC is proposing re: sustainability of burning forest biomass (think Drax), plus taster of Annex VI https://t.co/1SaDHaf1fG pic.twitter.com/pJoCMczU8P

— Leo Hickman (@LeoHickman) December 1, 2016

But NGOs have accused the EU of “greenwashing” its existing policies and giving a boost to bioenergy. Sini Eräjää, policy officer at EU Bioenergy, wrote in a blog post:

“In order to (supposedly) guarantee the ‘sustainability’ of biomass from forests, the Commission is proposing to only require that (i) the country of origin has some very basic forestry legislation and (ii) there is some form of accounting framework for land sector emissions (LULUCF) in place. In practice, these very lax requirements would not impose any new legal restrictions on any European country or, indeed, the majority of countries already exporting forest biomass to the EU (notably, Russia and the US).”

Individual participation

The proposed revision to the renewable energy directive also allows individuals and communities to generate their own energy, where previously individual nations had been able to restrict the right to self-produce. Individuals can also feed any excess energy they produce back into the grid and be paid for it at market value.

However, the amount of renewable capacity that can be installed is capped at 18MW per community, which could limit the ability of renewable cooperatives to take part in the EU energy market.

Governance

While the EU has set region-wide targets for 2030, there are no targets for individual member states for renewable energy or efficiency. The EU has proposed new governance regulations to ensure that the bloc hits its targets anyway.

If it looks like the EU is offtrack for its emissions, renewables or efficiency targets, then the Commission will be able to issue recommendations to member states to ensure targets will be met. Examples of actions that could be taken include financial contributions by member states that could be used to support new renewable energy projects across the union.