Electric cars sales in the US ‘could prevent one-tenth of global cropland expansion’

Josh Gabbatiss

07.18.22Josh Gabbatiss

18.07.2022 | 3:36pmA faster shift to electric vehicles (EVs) in the US would avoid around 10% of the global cropland expansion expected over the next 30 years, according to a new study.

Instead of growing maize (corn) to make biofuel for US cars, modelling in the Ecological Economics paper suggests large swathes of land could be left to absorb carbon dioxide (CO2).

This land sparing would bring “substantial” emissions savings, in addition to the direct benefits of electrifying US road transport, the researchers say.

The findings come as campaigners and some governments have been pushing to end the use of crops for biofuels in the face of soaring food prices and fears of global hunger.

One scientist not involved with the study tells Carbon Brief it highlights an “understudied” benefit of vehicle electrification, which “could have important indirect effects on agricultural production and greenhouse gas emissions globally”.

Shifting to 100% electric vehicle sales is a long way from reality in the US. However, the study suggests that, by choosing cleaner transport, Americans could significantly slash global demand for maize, cutting both emissions from agriculture and food prices.

Ethanol fuel

The US is the world’s largest maize producer, providing one-third of global supplies. Roughly, a third of this output is used to make ethanol.

Most petrol sold in the US has to contain up to 10% maize-derived ethanol. This policy has come about due to various factors, including government efforts to cut reliance on foreign oil, cut CO2 emissions and boost the rural economy.

However, biofuel expansion has driven land-use changes as farmers replaced forests and grassland with maize farms, which absorbs less carbon dioxide (CO2).

Moreover, many have questioned the logic of using so much agricultural land to produce ethanol, particularly during a global food crisis.

With this in mind, Dr Jerome Dumortier, associate professor in agricultural economics at Indiana University–Purdue University Indianapolis and the study’s lead author, says he realised that, as more fuel-efficient and electric cars hit the road, the demand for ethanol would likely collapse. He tells Carbon Brief:

“If you have more electric vehicles [in the US]…you basically free up 10% of global maize production.”

This topic is clearly on the radar of the US ethanol industry, whose members have expressed concerns in light of president Joe Biden’s policies to expand electric car use, including a non-binding goal for 50% of new US car sales to be electric by 2030.

Nevertheless, experts tell Carbon Brief that this issue has been largely overlooked in the scientific literature.

Maize models

Having undertaken similar work on fuel efficiency in US cars, Dumortier and his colleagues set out to explore the knock-on effects of rising electric car sales.

They modelled the demand for and use of cars and light trucks – known as “light-duty vehicles” – between 2015 and 2050, using projections from the US Energy Information Administration (EIA) as a baseline.

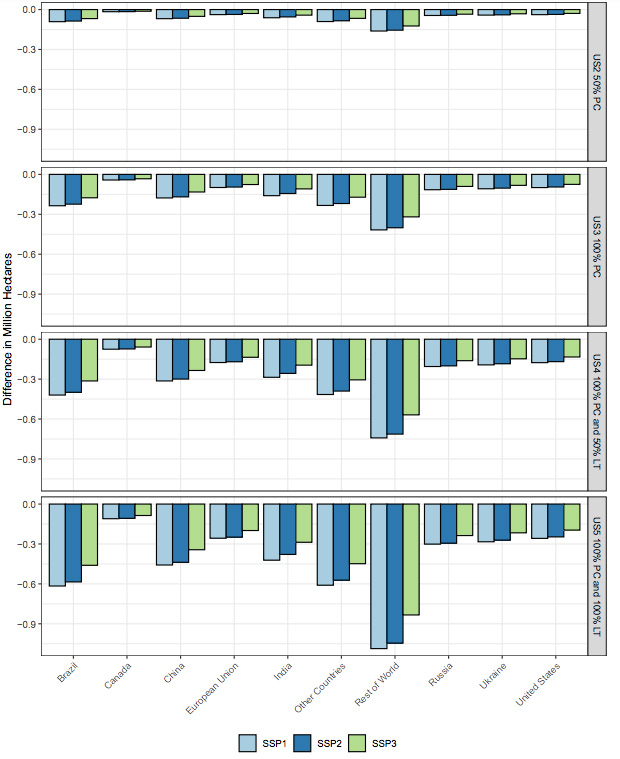

A variety of electric vehicle sales targets were then imposed by the researchers, ranging from 50% of cars up to 100% of both cars and light trucks by 2050.

The outputs from this modelling were then fed into a global “agricultural outlook” model, covering economic outcomes for maize as well as soybeans, rice and wheat until 2050, under the various electric car sales scenarios.

One key output from this stage was data on land allocation for crops. This was then used to calculate the biomass and soil carbon emissions linked to changes in agricultural land, using data on the potential for vegetation growth in different areas.

Finally, all of these assessments were conducted under three different Shared Socioeconomic Pathways (SSPs) – tools from climate science that allow researchers to model different futures for the planet, with different populations sizes, economies and attitudes towards collective action.

Even under the baseline scenario with no EV targets, the authors found that maize demand for ethanol would fall by 2050, due to increases in US vehicle fuel economy and electric vehicle market share. However, this drop in demand for ethanol would be far higher if all new vehicle sales go electric.

Declining ethanol demand would mean less land being used to grow maize, but not just in the US. In fact, the modelling suggests American farmers would end up exporting a lot of maize overseas, as Dumortier explains:

“The US is very efficient at producing maize…low cost, very high yields, very productive and, hence, you have this excess maize [which] is basically dumped on the world market.”

As maize becomes less profitable due to falling demand, this trickles through the entire global agricultural market, with farmers increasing their production of other crops and therefore bringing their prices down as well.

Land sparing

Under the study’s baseline scenario, the area of land used to grow crops expands out to 2050 by between 47m and 64m hectares, in order to feed a growing global population.

This has implications for the climate, as it could mean more carbon stores – such as forests – being converted into agricultural land.

But the authors found that if 100% of US vehicle sales were electric by 2050, between 5.1% and 9.4% of this expansion could be avoided.

As the chart below shows, avoided cropland expansion over the next three decades is highest in Brazil, China and India, and relatively low in the US itself. While this might mean lower economic output for those nations, from a climate perspective it makes sense, as Dumortier explains:

“If you think about the carbon stock…the US compared to other countries is actually relatively low…You’re not going to have some tropical forest growing in Iowa.”

By contrast, expanding Brazil’s croplands might initially bring economic returns, but would likely affect regions with large carbon stores.

The study concludes that the 100% electric vehicle sales scenario would result in between 417m tonnes of CO2 equivalent (MtCO2e) and 551MtCO2e being saved in total out to 2050, in addition to the benefits of taking fossil fuel-powered vehicles off the road.

Dr Kemen Austin, a policy analyst at RTI International who was not involved in the research, tells Carbon Brief that the study’s estimates for land-cover change linked to biofuel demand seem high compared to past research.

However, Stephanie Searle, who directs the US fuels programme at the International Council on Clean Transportation (ICCT) and was also not involved in the study, notes that land-use change modelling is “notoriously uncertain”. She tells Carbon Brief:

“Estimates vary widely depending on who you ask. So, even if the authors are estimating very high land-use change emissions per litre biofuel, that does not mean they are wrong.”

Extra benefits

Austin tells Carbon Brief that while lots of work has explored the impacts of rising biofuel demand, she is not aware of any research that calculate the opposite:

“This study highlights an important point that has been understudied thus far in the literature – that vehicle electrification could have important indirect effects on agricultural production and greenhouse gas emissions globally.”

The authors conclude that when assessing the emissions benefits of electric vehicles, avoided land-use change and emissions from agriculture should also be considered.

As it stands, the most recent projections from the EIA suggest that, with policies in place at the end of 2021, sales of battery and plug-in hybrid electric vehicles will still only be around 13% of light-duty vehicles sales in 2050 – a long way from the 100% modelled in the study.

However, this projection looks pessimistic when compared to the widespread view in the automotive sector that roughly half of electric car sales will be electric by 2030, in line with Biden’s target.

Searle says that despite the clear benefits of cutting biofuel use to free up land, she thinks it is unlikely that the US government will acknowledge this given its enthusiasm for “actively promoting biofuels”.

The Guardian reported in June that the US would “press ahead with biofuels production, the deputy secretary for agriculture has said, despite increasing concerns over a global food crisis”.

Dumortier et al. (2022) Light-duty vehicle fleet electrification in the United States and its effects on global agricultural markets, Ecological Economics, doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2022.107536

-

Electric cars sales in the US ‘could prevent one-tenth of global cropland expansion’