Renewable electricity developers are doing themselves out of a job. According to anti-wind group the Renewable Energy Foundation, they should finish what they’re working on and pack up, because we don’t need any more of their power.

Its latest report says there are already enough renewable energy projects built, under construction or given consent to meet our targets. That means there are many more applications causing needless anxiety for homeowners when they could be scrapped.

Conservative energy minister Michael Fallon has been leading his party’s charge against onshore wind turbines and is likely to welcome these conclusions. There are only two problems with the REF report. It makes impossibly optimistic assumptions about renewable build rates. And it assumes the UK can start breaking its own laws after 2020.

Will 35 gigawatts (GW) be built by 2020?

First, let’s look at REF’s assumption that 35GW of renewable electricity capacity will be built by 2020.

REF says:

“35 GW of renewable electricity capacity across all renewable technologies has now been consented by the planning systemâ?¦ It is very likely that those awaiting construction will actually be built.”

The 35GW figure for operational, under construction or consented capacity seems to be broadly accepted. It is pretty much in line with the Department of Energy and Climate Change (DECC) renewable energy roadmap, which was updated last November.

About half of that capacity (16GW) is operational now. Another 4GW is being built. These are the bankers.

Views start to diverge on the next 15GW of consented capacity, however. REF says it is “very likely” to be built and so assumes that all of it will be. But DECC tells Carbon Brief that not all consented projects will be built.

DECC data shows that at least 10 per cent of consented onshore wind turbines and 20 per cent offshore never get built, according to trade body Renewable UK economics policy officer Alex Coulton. Recent changes to policy, not least the Conservative’s now officially anti-wind stance, make it likely that an increasing number of consented projects will fall by the wayside in future.

This can and already has happened. Nearly 6GW of consented offshore windfarm capacity has been scrapped in the past 6 months. So at least some of those planning applications will be needed to reach 35GW of renewable electricity capacity in 2020.

Is 35GW enough to meet EU targets in 2020?

Next, let’s look at the REF’s assertion that 35GW is all we need to meet EU targets. The UK has agreed to an EU target to produce 15 per cent of its energy from renewable sources in 2020. This includes renewable electricity, renewable heat and renewable transport fuels.

REF says 35GW of renewable electricity capacity is enough to meet half of this target, in line with DECC plans published in 2009. But a DECC spokesperson insists it didn’t actually specify which technology should be used to meet the 2020 target.

Plans for renewable heat and transport fuels are well behind schedule, a spokesperson for industry group the Renewable Energy Association tells us. More renewable electricity would then be needed to plug the gap.

Even if it is not needed, the government has set up a ‘levy control framework’ (LCF) to limit the amount of money spent subsidising renewable electricity. This will cap the amount of new capacity that is built by setting a 7.6bn annual LCF budget for 2020/21.

If too many projects apply for subsidies under this budget, DECC will hold auctions to hand money to the cheapest renewables first.

Will the government of 2020 break its own laws?

Finally, REF’s report seems to assume there is no need to build more renewables once the EU 2020 target has been met. It is true that there is currently no EU target for renewables in 2030. The UK has been one of the major opponents of such a target.

But other targets still apply, not least the UK’s legally binding Climate Change Act that requires an 80% cut in carbon emissions by 2050. This law could be scrapped. For now, though, it is still supported by all the major political parties.

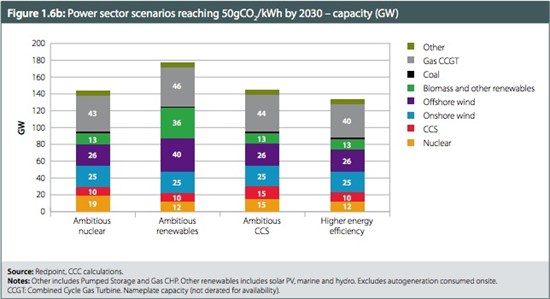

There a a number of ways to reach the binding 80% carbon reduction. All of them involve a substantial increase in renewable electricity capacity beyond 2020, according to the government’s Committee on Climate Change.

Its projections involve at least 64GW of renewable electricity capacity in 2030 (see chart). That’s nearly double the 2020 figure and four times current capacity. It’s also a minimum that assumes ambitions on nuclear power, carbon capture and storage or energy efficiency are ramped up significantly.

Unless the government of 2020 plans on breaking its own laws it better hope renewable developers keep on building.