The UK doesn’t need any new laws to go all out for shale gas, according to Prime Minister David Cameron. Is he right – and what do the rules governing fracking really look like in this country?

The ability to extract shale gas has lowered gas prices and increased energy security in the USA. But it’s also prompted controversy. Fracking has led to air and water pollution, water shortages and posed a threat to human health, environmentalists argue.

The Royal Society suggested in 2012 that the impacts are manageable – but only under a strong regulatory system. The government says no new laws are needed to make the shale gas industry safe, however.

So where does this leave us? A Guardian editorial says it means worried communities will have to rely on ” trust” in the oil and gas industry and regulatory bodies to get it right. Others disagree, however.

UK: a strong regulatory environment?

Cameron boasts this country already has “one of the most stringent” regulatory systems for oil and gas extraction in the world, so we don’t need any more laws to make fracking safe. The industry already has to comply with “nine or ten” European Directives governing the safety of the industry, according to Ken Cronin of the industry group UKOOG.

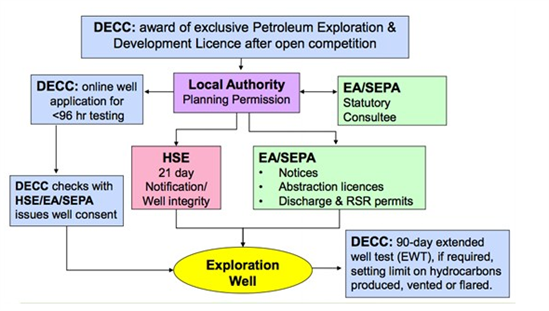

An energy company that wants to explore for shale gas has to consult with the local council, the Department for Energy and Climate Change, the Environment Agency and the Health and Safety Executive. Here’s the process in a bit more detail:

Source: Presentation by the EA’s head of environmental policy Tony Grayling, March 2013

In order to get planning permission, it has to apply for a series of permits from the Environment Agency (EA). The EA is going through the process of developing what that permitting process looks like. This mainly consists of consolidating regulations that already exist elsewhere into one place.

No leakage

Professor Robert Mair, lead author of the Royal Society’s report, says this system is strong enough as it is. The UK has a “pretty robust regulatory environment”, he argues, agreeing with the government’s position that there isn’t a case for piling on more regulations.

Mair and Cronin both argue that many of the problems experienced in the USA are down to poor ‘well integrity’ – in other words, wells that leak. This problem is less likely to recur here, they say, because the (HSE) monitors wells to make sure they are not vulnerable.

Mair describes the HSE’s role in monitoring the safety of wells as “absolutely paramount” in ensuring the safety of the industry.

Scaling up the industry

There is one rider to all this optimism, however. The shale gas industry in this country is at a very early stage. So far, a few companies are exploring for shale gas, and just one company has tried fracking.

The government has some pretty ambitious plans for changing that in the future. If it’s going to make sure the industry’s safe, it needs to provide the resources to make sure regulations are implemented, according to Mair.

This could be a problem. At the moment, the EA has only six full time staff dedicated to the issue, according to a story in the Independent. And the Agency is currently in the process of implementing a 15 per cent cut to its workforce. There doesn’t seem to be any guarantee of how much resource the government will commit to this in the future.

Trusting industry practice

Environmental group Friends of the Earth (FoE) says it is also concerned that the EA’s underlying objective is to “streamline regulatory processes” rather than develop strong regulations. In its consultation, released in August, the EA says it takes a “yes if” approach to planning, and avoids objecting where it can. FoE is worried that the guidance taken as a whole creates in effect a presumption in favour of development, rather than the reverse.

It also says it’s “troubling” that the EA “relies on industry guidance, or work undertaken by the industry” as the basis for its regulatory requirements. Mair argues that relying on industry best practice isn’t a problem, however. He says:

“Best practice is in the end the responsibility of the operator. This isn’t to be confused with the operator getting away with sloppy practices when no-one’s looking â?¦ but there is an element where day to day controls have to be down to the operator. The role of the independent well examiner is also very important, as set out in our report“.

Assessing risk, and creating capacity

The oil and gas industry has a troubled history, and problems do occur despite regulation. The HSE, for example, is currently investigating energy company Total over a gas leak from its platform in the Elgin field in 2012. Total has also just announced plans to invest £35 million in the UK’s shale gas industry.

Mair argues that we can reduce the risk to a small value – but, as with many other human activities, “There is no such thing as zero risk”.

The system is also highly complex – covering a wide range of issues including air and water pollution, gas flaring, water supply and ‘fugitive’ emissions. This makes it difficult to know whether there are any flaws in the system, and where they might lie. In this sense, the public does have to trust regulators and the government to get it right.

And even if the government has a perfect regulatory system, it needs to commit enough capacity to implementing it. Otherwise all the rules in the world won’t make any difference.