Roz Pidcock

23.06.2014 | 10:45amIn the 2000s, the question of how strong agreement is among climate scientists that climate change is happening and that it’s human-caused began to gain prominence.

A few papers sought to answer the question using various different approaches, ultimately pinning the level of consensus at around 97 or 98 per cent.

Last year, a study by University of Queensland climate scientist and founder of the Skeptical Science website, John Cook, revisited consensus on climate change within the scientific literature.

The researchers examined 12,000 studies. Similar to other studies, Cook et al. concluded that 97 per cent of the papers that expressed a position on the causes of climate change pointed to human activity as the main driver.

The study received a lot of media coverage at the time, ranking 11th among new science papers receiving the most attention online in 2012, and even earning a mention from the US president. But it’s alsoprompted some heated discussion.

Most recently, economics professor Richard Tol published a critique of the paper in the journal Energy Policy. Tol takes no issue with the paper’s conclusion about an overwhelming scientific consensus in the literature. Instead, the crux of his argument is with specifics of the methodology.

Consensus is complicated. And reducing a complex question to a simple number is going to be fraught. So why do it? We asked climate scientists what consensus means to them, if it can be measured and how they use consensus in their own work.

Why measure consensus?

Climate scientists overwhelmingly agree that recent warming is being driven by human activity rather than by naturally occurring processes. That’s typically what people mean when they talk about a ‘scientific consensus’ on climate change.

The consensus is so strong because scientists can be sure of the fundamental physical principles underpinning greenhouse gas warming. Indeed, journalist Seth Borenstein recently quoted a scientist equating the strength of the evidence with that linking smoking with lung cancer.

Source: Associated Press via Huffington Post 24th September 2013

However, studies have shown that outside scientific circles, a large proportion of the general public is not aware such overwhelming agreement exists among climate scientists. A recent US poll suggested just one in ten people put the figure at more than 90 per cent.

According to the authors, the motivation for the Skeptical Science paper is that studies suggest people are more likely to accept human-caused climate change – and action to tackle it – once the broad agreement between scientists is highlighted. Richard Allan, professor of climate science at the University of Reading, explains how the study may have helped connect the dots in public minds:

“[T]he analysis of Cook et al. was probably useful in dispelling the myth sometimes portrayed by the media that there is substantial debate over the robust scientific evidence relating human activity to current and future climate change, which there isn’t.”

Communicating consensus

Others argue there’s only so far this approach can go towards correcting the mistaken impression in the public consciousness that there’s disagreement among scientists – referred to as the “consensus gap”.

Dan Kahan, professor of psychology at Yale Law School explains a concept known as “motivated reasoning” – where people selectively use or dismiss evidence depending on whether it is consistent or inconsistent with their worldviews or cultural bias. Release as many statements of consensus as you like, Kahan contests, you’re just preaching to the choir.

The value of consensus can still be communicated effectively, argues Dr Adam Corner, psychologist at Cardiff University, in a recent Guardian article:

“The challenge is not to find a non-political way of engaging people on climate change, but to embrace the fact that politics permeates the discourse on climate change â?¦ pointing to a row of nodding scientists and expecting this to catalyse public concern is not going to get us far – no matter what the ‘magic number’ attached to the consensus is.”

Source: Guardian Sustainable Business 19th June 2014

A political contribution

Another point worth noting is that in pursuit of a single number to capture consensus, the answer you get depends on the question you ask, explains Professor Kevin Trenberth, climate variability expert at the US National Centre for Atmospheric Research:

“Very small changes can change the perceived consensus easily. 97% of scientists may agree that global warming from humans is happening but add any qualification like its timing or magnitude and it would change.”

And this can be unhelpful if clear communication is the objective. Arguing over what the precise number should be runs the risk of giving the impression there’s more uncertainty among scientists than there is. As long as there appear outwardly to be arguments over consensus, it’s easy for those who wish to discredit the science to avoid engaging with the level of agreement that really exists among scientists.

Nuances aside, the scientists we spoke to generally tended to see the value of emphasising the broad strength of consensus for communication purposes. Andrew Dessler, professor of atmospheric sciences at Texas A&M University, explains:

“After all, if you’re looking for an expert medical opinion, and you find out that 97 per cent of the specialists agree about the course of treatment, you can be justly confident that that’s the best advice that medicine can give you”.

But to the climate science community, the paper’s conclusions come as no surprise. Independent climate researcher professor James Annan explains:

“I don’t think the Cook et al paper really told us anything we didn’t already know (where “we” here is the vast majority of climate scientists), and as such it wasn’t really much of a scientific contribution. That’s not to say it wasn’t worth doing, but it was clearly playing more in a political than scientific sphere.”

In fact, consensus isn’t a word you’re likely to hear being discussed in scientific circles, Dessler tells us.

“The only time I hear about “consensus” is in the public debate over climate. Scientists never ever talk about consensus – by going to meetings and reading the peer-reviewed literature, you can figure out what your colleagues think”.

Consensus: a step on the road to scientific progress

Though it may not be much of a conversation topic among scientists, consensus as a concept has a fundamental place in driving scientific progress. Dessler continues:

“For each question that arises (e.g., is the earth warming?), there comes a time when the evidence is so overwhelming that the experts independently realize that the problem is essentially solved â?¦ At that point consensus exists on the answer and the question is no longer interesting – and scientists move on to the next interesting question”.

So it’s important to understand consensus as the product of a body of research rather than the starting point, Annan explains:

“[W]e don’t do research by agreeing a consensus – rather, it is what emerges where we can no longer find arguments.”

Arriving at a consensus – even if it’s an an unspoken one – drives scientific progress by taking research in new directions, Dessler adds:

“Consensus determines what we know, and it also determines what we don’t know. [It] also determines what the interesting questions are, which in turn determines what people work on â?¦ [T]he question of whether the earth has warmed over the last century is not an interesting question. We have firmly established that has. So people don’t spend much time working on that.”

On the other hand, scientists are working very hard to understand to why surface temperatures haven’t risen as quickly in the last decade and a half compared to previous ones – a far more interesting topic, says Dessler.

A growing body of research suggests the surface warming slowdown can be explained by a strengthening of Pacific trade winds, causing more heat to find its way to the deep ocean rather than staying at the surface. Such natural variation is by its nature short-term, and scientists expect the long term warming trend to continue.

How a scientific idea evolves

The very early stages of exploring a new topic in any area of science is the evolution of a hypothesis to a theory. This happens as evidence builds up to either support or refute it.

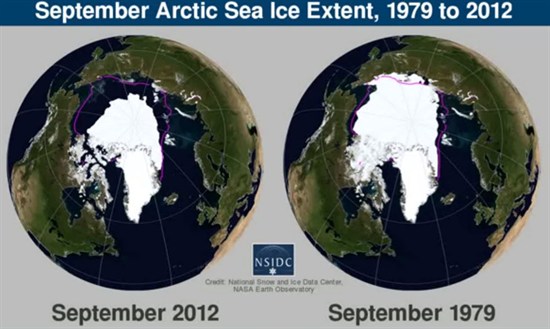

Map of Arctic sea ice extent in 2012 compared with 1979. Purple line shows 1979-2012 long term average. Source: National Snow and Ice Data Centre (NSIDC) See full video here

A good example of a new and still very speculative field is whether diminishing Arctic sea ice is linked to Northern Hemisphere extreme weather. Professor Jennifer Francis, whose work proposing a connection prompted most of the research in this field, explains:

“Consensus comes in wherever there isn’t absolute proof of a theory, which is most of the time. In my work regarding links between rapid Arctic warming and changes in weather patterns, I would not say we have a consensus yet. When you do achieve consensus, it’s when a hypothesis transitions to a theory â?¦ This is a key distinction in science.”

In other words, broad agreement on certain fundamentals of climate science can coexist alongside less agreement in other areas. A very clear illustration of this is the recent report by the UK’s Royal Society and the US National Academy of Sciences, which lays out what scientists know about climate change, where consensus is growing, and where there is still uncertainty.

Consensus comes in many guises

There’s no doubt that consensus as applied in the scientific world is a complicated concept. Each time consensus pops up in the media, it raises interesting questions about how to measure it and what expressions of consensus mean in different scientific, social and political contexts.

However we choose to talk about consensus, all we’re really doing is exploring how to present scientific facts to different audiences. The facts themselves don’t change. That an overwhelming consensus exists among scientists about human-caused climate change isn’t in doubt. But then again, it never was.