Robin Webster

24.04.2014 | 4:00pmThere’s “no requirement” for the UK to put up any more onshore wind turbines after 2020, according to energy minister Michael Fallon. But evidence from a government advisor suggests capping onshore windfarms will make it a lot more difficult and expensive to hit our climate targets.

The next government will scrap subsidies for onshore wind from 2020 if the Conservatives win the election, the party confirmed today. This would essentially place a freeze on new wind turbines from the end of this decade.

But Tories say they’re not rowing back from commitments to cut carbon emissions. The country’s got enough onshore wind in the pipeline to meet our renewable energy commitments, and “there’s no requirement for any more,” Fallon told the BBC this morning, adding that other technologies can be used to cut emissions.

The idea that the UK can stop expanding onshore wind farms and cost-effectively keep up with plans to cut carbon emissions is at odds with evidence from experts including the government advisor the Committee on Climate Change (CCC), however.

Wind expanding to 2020

The UK wind industry is expanding rapidly. Onshore turbines generated 7.7 per cent of the country’s electricity last year, up from 5.5 per cent the year before.

It’s an impressive rate of growth – although the absolute density of turbines is still a lot lower than in some other European countries. For instance, we still only generate half as much power from onshore wind per unit area as Spain, and a quarter of the amount Germany generates related to its landmass, the CCC says.

The government has encouraged UK onshore wind as part of its attempts to meet a European Union (EU) renewable energy target. It requires the UK to source 15 per cent of its energy from renewables by 2020.

To hit the target, the government believes it needs about 13 gigawatts (GW) of onshore wind online by 2020. The country already has nearly seven GW of onshore wind in place, and there’s a lot in the pipeline.

Figures from the Department for Energy and Climate Change suggest that once wind projects under construction or granted planning permission are taken into account, the UK will have 11 to 13 GW of onshore wind power by 2020.

Emissions cuts don’t stop in 2020

13 GW is enough, the Conservatives argue: the UK can stop there and concentrate on developing other renewable technologies, like offshore wind. The 2020 renewable energy target would have been achieved, and the EU hasn’t set binding country-level targets for 2030 in the same way, so there aren’t any other targets to deliver.

But there is one relevant target, and it’s in UK law. Under the legally-binding Climate Change Act, the government has committed to reducing the country’s greenhouse gas emissions by 80 per cent overall by 2050.

The CCC says if the country’s going to reduce greenhouse gas emissions in line with its targets under the act, the power sector must be emit virtually no greenhouse gases by 2030. This means onshore wind capacity must keep rising to 25 GW by 2030, it suggests.

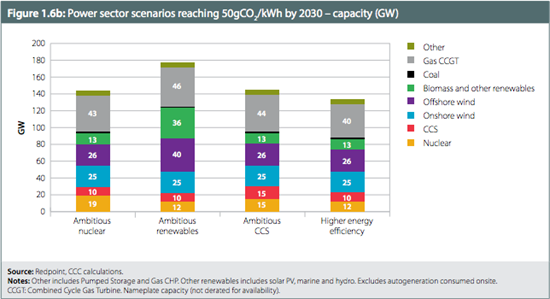

The graph below illustrates the CCC’s different projections for the power sector in 2030. The scenarios vary according to different sets of circumstances – ambitious energy efficiency policy, for example, or development of nuclear power.

But they have one thing in common – they all suggest onshore wind will produce 25 GW of power in 2030:

Source: Committee on Climate Change, May 2013

The UK currently produces 7 GW of power from onshore wind, so that will be a pretty big jump. It is technically feasible, however, trade industry body Renewable-UK has told Carbon Brief.

It would mean the UK generating the same amount of energy per unit area from onshore wind as Germany does at the moment, the committee says. There is one key difference – UK has a higher population density than Germany so the impact on local communities would be greater.

But the majority of this expansion could be achieved without placing turbines in new sites. Instead, it could be done by replacing old wind turbines that have reached the end of their lives with more efficient models, Renewable-UK tells us. ‘Repowering’ old sites with new wind turbines can potentially triple the output of a windfarm, it says. This means there’s a lot of potential for this kind of expansion – if the policy environment allows it.

Cutting emissions at higher cost

But what if the UK did freeze onshore wind capacity? It would certainly be possible for the UK to do so in 2020 and keep cutting carbon emissions for another three decades – but it would be a lot more expensive.

Onshore wind is a well developed technology, and it’s relatively cheap compared to other low-carbon power sources. Experts from the Royal Academy of Engineering recently estimated replacing a single onshore wind turbine with an offshore wind turbine would cost £300,000 in government subsidies, for example.

The government expects the cost of offshore wind to come down in the 2020s – but not enough to overtake onshore wind. Overall, investing in 10 GW of onshore wind in the 2020s rather than other less-developed clean technologies could save the economy two to three billion pounds, the CCC predicts.

Or to put it another way – failing to invest in 10 GW of onshore wind could cost the country two to three billion pounds in the 2020s.

By 2030, onshore wind will still be cheaper to develop than offshore wind, and gas or coal power stations fitted with carbon capture and storage (CCS) technology, the CCC says. This is illustrated in the graph below from its report, which places onshore wind in the furthest green box in the left:

Source: Committee on Climate Change, May 2013

Cutting emissions, cheaply

The committee’s projections are based on the assumption the UK will maintain its commitment to cutting carbon emissions. Of course, that may not happen – and the country may generate energy even more cheaply from coal or unabated gas if it ditches its obligations under the Climate Change Act.

The Tories maintain they are committed to cutting emissions, however. The Prime Minister recently told Parliament man-made climate change is “one of the most serious threats that this country and the world faces” and on the European and international stage, the UK government continues to push for ambitious carbon reduction commitments in the 2030s and beyond.

Ministers have also emphasised the need to do so cheaply. In February, George Osborne argued it’s important not to be too “theological” about which technology to use in tackling emissions. The most important deciding factor should be the need to cut emissions “in as cheap a possible way as we can”, he said.

In setting a freeze on onshore wind turbine expansion, the Tories appear to be going in the opposite direction. The Tories’ plan to cap wind power could ensure tackling climate change will be more expensive, not less.