Countries fail to set shipping climate target

Sophie Yeo

05.14.15Countries rejected the opportunity to place a global emissions reduction target on the shipping industry at a meeting of the International Maritime Organisation in London this week.

Proposed by the Marshall Islands, this would have been the first time that a cap was placed on the sector, which is projected to grow in the decades ahead as trade and the world economy expands.

But the lack of consensus over how to collect data on shipping emissions put a stranglehold on the discussions, with many nations unwilling to sign up to an emissions reduction goal without a sure way to measure progress.

A growing sector

More than 90% of global trade goes by sea. According to the IMO, there were more than 104,000 ships in the world registered in over 150 nations in 2010.

This comes with an environmental cost. Shipping is responsible for around 3.1% of global carbon dioxide emissions. Every year between 2007 and 2012, ships emitted an average of one billion tonnes of carbon dioxide – more than Germany.

Total global emissions must fall to net zero in the second half of the century in order to have a good chance of meeting an international target of limiting average temperature rise to below 2C, according to the UN’s panel of climate scientists.

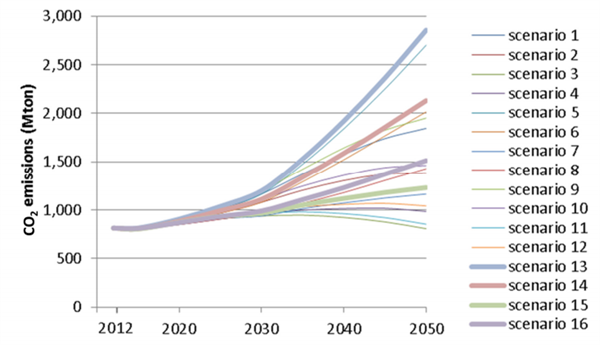

Yet shipping emissions are projected to grow in the coming decades. A recent report by the IMO projects they will grow by 50-250% by 2050, depending on economic and energy-related development. All IMO scenarios, bar one, put emissions by the middle of the century at a higher level than they were in 2012.

Projections of CO2 emissions from international maritime transport. Bold lines are business as usual scenarios. Thin lines represent efficiency improvements, emissions controls, or both (for full explanation of scenarios, see IMO report, p.161). Source: Third IMO GHG Study 2014

Yet there has so far been no concerted effort to reduce emissions across the board.

Attempts to reduce the emissions of ships have been based on new rules to improve the efficiency of new and existing ships. These mandatory measures were adopted in 2011 and entered into force on 1 January 2013.

This means that new ships must become 10% more efficient by 2020 in terms of grammes of carbon dioxide emitted for every tonne carried over a mile. This increases to 20% by 2025 and 30% by 2030. Existing ships must submit an energy efficiency management plan, designed to encourage owners to optimise the performance of their ships.

The International Council on Clean Transportation predicts that these regulations could save up to 263 million tonnes of carbon dioxide being emitted every year by 2030, compared to a business-as-usual scenario.

But these targets will not put the shipping industry on course to absolute emissions reductions.

In other words, at the same time as many countries are bending their carbon emissions downwards, the shipping industry will continue to increase its contribution to the global pool as demand for shipping grows. In 2013, the weight carried by the global fleet, including cargo and passengers, increased by 4.1% from the previous year.

International seaborne trade (millions of tonnes loaded). Source: UNCTAD Review of Maritime Transport, various issues

A 2013 paper by scientists at Manchester Metropolitan University predicted that, by 2050, shipping could contribute 6-18% of the total permissible emissions globally if temperatures are to be kept below 2C.

Not enough action

The shipping industry has backed the international target of keeping global temperatures below 2C, yet the failure to agree on an emissions reduction target could undermine these good intentions.

At the UN’s 2011 climate conference in Durban, the IMO’s marine environment director, Jo Espinoza-Ferrey, told delegates that international shipping would make a “fair and proportionate contribution” to global emissions reductions.

However, he also acknowledged that the freshly agreed targets of the IMO to improve ship efficiency were not enough. He told the conference:

“It has been recognised that, in spite of the expected emissions reductions, the adopted technical and operational measures may not, by themselves, be sufficient, over the longer term, to meet the overall reduction objectives and the two degrees target agreed in Cancun last year – particularly in view of the growth projections for world trade and, as a consequence, of shipping.”

Further action would be necessary, he said, including a market-based measure that would mean ship owners having to pay for their emissions, providing a financial incentive to become greener. He added that the IMO hopes to have “yet another good story to tell in a few years’ time”.

Four years later, and this cliffhanger has yet to be resolved. It is not necessarily for want of trying.

Up to 2013, there were in-depth discussions over the possibility of an emissions trading system that would force down shipping emissions.

Several countries submitted their proposals for a possible scheme, including Cyprus, Denmark, the Marshall Islands, Nigeria, Japan, Jamaica, US, Norway, UK, France and the Bahamas. Some of these proposed an emissions reduction target or a cap for the industry.

But in May 2013, all discussion of the topic was suspended to an unspecified future session.

Difficulties

There are a number of reasons why countries have struggled to impose an effective regime to reduce shipping emissions.

One issue that is still unresolved is a lack of shipping emissions data, which makes it difficult for ship operators to impose new measures to clean up their fleet.

The EU has made efforts to fill this gap. In April 2015, Brussels diplomats agreed a new regulation that will see emissions data collected and published for all large ships that use EU ports, regardless of where they are registered.

But in the commercial world of shipping and trade, such gestures towards transparency have not been universally welcomed. Gerhard Strasser, advisory council chairman at the International Towing Tank Conference, which collects data on shipping efficiency, tells Carbon Brief:

“There are so many different interests involved, and that’s why it’s so complicated to come to one common agreement. The IMO does not want to follow the European community because there are other interests worldwide, so the problem now is to come to an international, common system, and this is going to take some time.”

In addition, there is the fundamental clash of principles between the efforts of the UN’s climate body (UNFCCC) and the IMO when it comes to reducing emissions.

The UNFCCC makes decisions based on the concept of “common but differentiated responsibility and respective capability”. This means that the richer countries that have historically been responsible for causing climate change have to take on the bulk of the actions today to solve it.

In the IMO, however, this would lead to a dead end. If one nation imposes less desirable regulations, a ship can simply “reflag” under another country. An unequal distribution of new climate regulations is unlikely to dent the carbon footprint of an industry that can quickly jump into the arms of a less demanding jurisdiction.

This has an obvious negative repercussion on the original flag state. When Honduras tightened its regulations in 1991, for instance, its shipping registry dropped to less than one million tonnes of shipping capacity. More relaxed states such as Liberia had registries with 52.43 million tonnes.

To make sure this does not happen, the IMO instead acts on the principle of “no more favourable treatment”, which stipulates that its rules must apply to all ships equally, regardless of their flag.

Campaign groups Oxfam and WWF have suggested that, in order to overcome this clash of principles, money generated by any carbon tax imposed on the shipping industry could be poured into the UN’s Green Climate Fund – a bank designed to fund green projects in developing countries.

Marshall Islands action

Under the UNFCCC, countries are working on an internationally binding deal to reduce emissions, set to be signed in Paris at the end of this year. The current draft of this agreement touches only very briefly on the role of shipping, shunting it back to the IMO:

“In meeting the 2C objective, Parties agree on the need for global sectoral emission reduction targets for international aviation and maritime transport and on the need for all Parties to work through the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) and the International Maritime Organization (IMO) to develop global policy frameworks to achieve these targets.”

It is still possible that this – and one other suggestion for a shipping levy, with cash going into the UN’s Adaptation Fund – could be stripped from the final agreement.

This week, the Marshall Islands proposed that the IMO should adopt a “quantifiable and ambitious” target to reduce emissions from shipping in line with keeping the world below 1.5C – a limit to planetary warming that the country has repeatedly called for within the UN’s climate negotiations.

These tiny islands, located in the Pacific, hold the third largest shipping registry in the world, which provides the developing nation with one of its few sources of regular income.

This is a double-edged sword: while its economy is dependent upon this polluting sector, it also faces an existential threat due to the sea level rise caused by climate change.

The proposal was non-prescriptive regarding how countries should achieve whatever goal they might choose to adopt. The exact target for the industry would also be part of future debates.

Failure

But the proposal did not gain the necessary support from other countries to be able to succeed, with objections including the lack of process to collect and monitor emissions data and the need to wait for an outcome from the UN climate talks taking place in Paris this December.

While some states, including France, Latvia and many other small islands, backed the Marshalls’ proposal, they faced pushback from others including Russia, India and China. The chair concluded that the the issue could be taken up again in a future session.

Tony de Brum, Marshall Islands foreign minister, tells Carbon Brief:

“The Marshall Islands are very, very pleased with the countries that actually voiced support for our proposal, but we were disappointed the IMO itself did not accept that show of strength as a signal to do its part to move forward instead of saying, ‘We’ve taken note of the filing and we’ll wait until someone else does something about it first.'”

But the failure of the proposal this time around does not mean that that the shipping industry will be given a free ride forever, says Simon Walmsley, marine manager at WWF. He tells Carbon Brief:

“The supply chain and civil society are demanding informed choices, in particular linked to carbon footprint. I suspect if this does not occur the sector may lose credibility and even business. The sector is no longer out of sight out of mind and will be under increasing scrutiny. Perhaps UNFCCC processes will push the sector to go beyond efficiency measures.”

Changes to the shipping industry come slowly, but are necessary as part of the global effort to keep global temperatures to below 2C.

Small island states such as the Marshall Islands feel this necessity more keenly than anyone, and have shown their willingness to put their own financial interests on the line in order to secure their long term survival.

Main image: Cargo ship underway viewed from bow.

-

Countries fail to set shipping climate target at meeting of the International Maritime Organisation