COP29: What is the ‘new collective quantified goal’ on climate finance?

Josh Gabbatiss

11.04.24Josh Gabbatiss

04.11.2024 | 5:18pmAs nations assemble at COP29 in Baku, Azerbaijan, one issue is expected to dominate the summit: climate finance.

In total, countries need to invest trillions of dollars to build clean-energy systems, prepare for an increasingly hotter world and deal with the aftermath of climate change-fuelled disasters.

The UN climate convention also specifically requires developed nations to provide financial resources – usually referred to as “climate finance” – to help developing countries do this.

Under the Paris Agreement, governments agreed to set a new climate finance target by 2025 that would channel money into these nations and help them tackle climate change.

But negotiations over this “new collective quantified goal” (NCQG) for climate finance in recent months have exposed deep divides in the UN climate process.

Nations disagree on virtually every element of the NCQG, including the amount of money that needs to be raised, who should contribute, what types of finance should feed into it, what it should fund and what period of time it should cover.

Developing countries are looking to high-income parties, such as the US and the EU, to provide the money. Meanwhile, developed countries want an all-encompassing goal that includes input from private companies and large, emerging economies, such as China.

In this article, Carbon Brief explores the issues countries have been clashing over, which will have to be resolved to secure an outcome in Baku.

- Why are countries discussing a new climate finance goal?

- What number will replace $100bn in the new target?

- Which countries will contribute to the new target?

- What sources of money should be included in the NCQG?

- What kind of activities will the NCQG support?

- How long will countries have to meet the NCQG?

- How will progress towards the target be reported and tracked?

Why are countries discussing a new climate finance goal?

Climate finance is at the heart of international climate politics. It is widely understood that developing countries need to invest large sums of money if they are to cut their emissions and prepare for a hotter world, in line with their climate plans.

The nature of climate finance is disputed, but, currently, it largely comes from developed countries’ aid budgets and contributions from multilateral funds and development banks (MDBs), such as the World Bank. Smaller amounts come from the private sector.

When nations negotiated the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) in 1992, the treaty said that developed countries “shall provide” financial resources to help developing countries tackle climate change.

In 2009, developed countries agreed to “mobilise” $100bn of climate finance a year by 2020 – an annual target that was meant to run through to 2025. This became a fraught topic, as developed nations missed the 2020 deadline and only reached it two years later in 2022.

In the Paris Agreement of 2015, Article 9 reaffirms that “developed country parties shall provide financial resources to assist developing country parties”. Nations also decided that, before 2025, they:

“Shall set a new collective quantified goal from a floor of $100bn per year, taking into account the needs and priorities of developing countries.”

This “new collective quantified goal” (NCQG) is the focus of negotiations at COP29. With the 2025 deadline approaching, this will be the final opportunity to settle on the new target.

Negotiators have been gathering for months to discuss the issue, in an effort to find a landing ground. However, the NCQG is both very technical and highly politicised, leaving them deadlocked on most issues.

Following several rounds of negotiations, the co-chairs (from Australia and the United Arab Emirates) overseeing the talks were tasked with producing a “substantive framework for a draft negotiating text”, which would form the basis of COP29 deliberations.

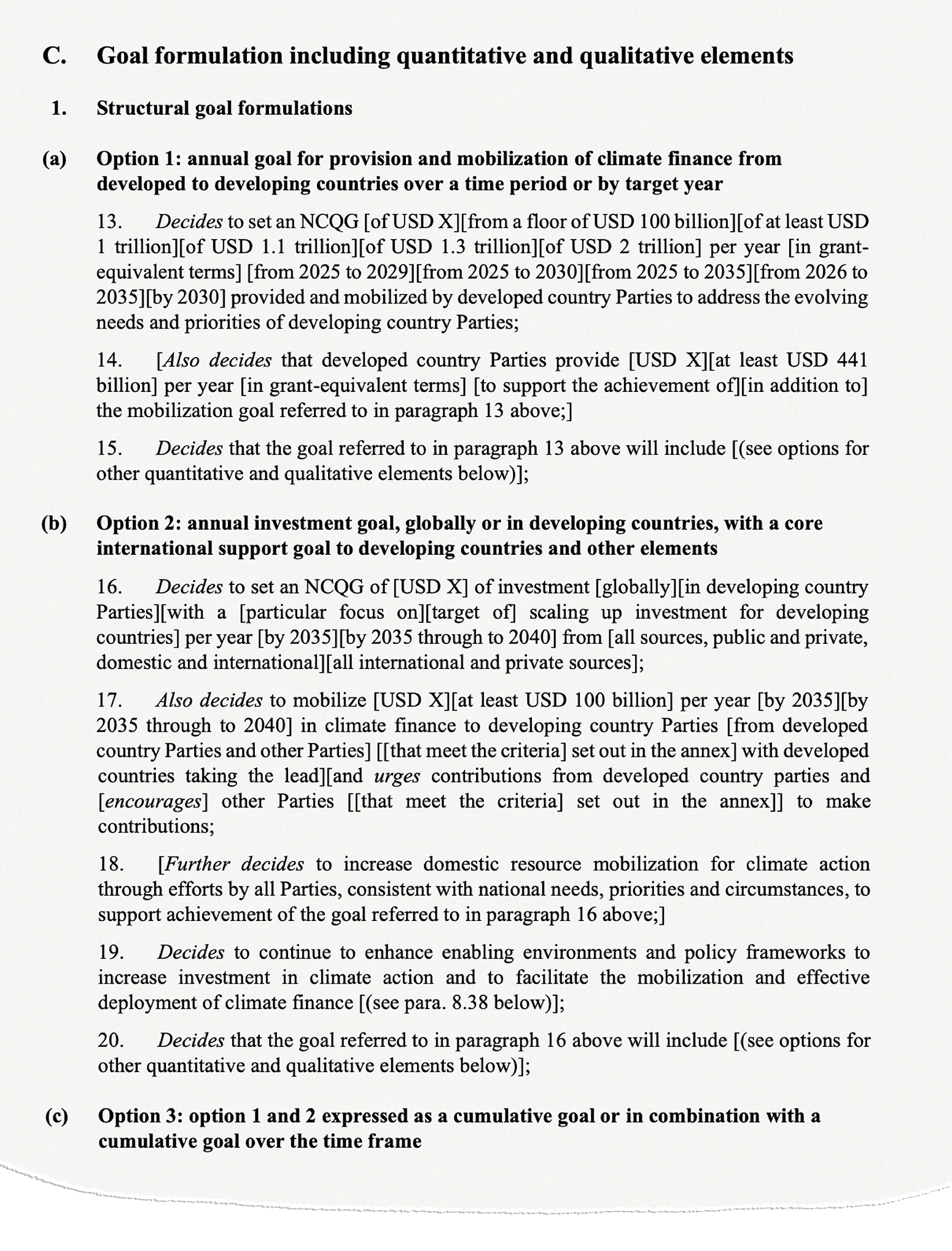

The resulting document offers the outlines of the new climate finance target and crystallises the key areas of remaining disagreement. It is nine pages long and contains 173 elements that are still in square brackets, meaning they are undecided.

What number will replace $100bn in the new target?

Unlike the $100bn, which was an arbitrary number put forward by global-north leaders, the NCQG must take into account the “needs and priorities of developing countries”. Many assessments have shown that these nations’ investment needs will run to trillions of dollars for tackling climate change in the coming years.

However, setting a numerical climate finance target – or “quantum” – is not straightforward. Many of the future demands of dealing with climate change are difficult to quantify and there has been no officially mandated effort to work out what these needs are under the NCQG.

The closest attempt is the “needs determination report” from the UN Standing Committee on Finance, based on combining various reports in which developing countries have self-assessed their own requirements. However, the committee stresses that its estimate of $5-6.9tn over the next five years contains “significant gaps” and, therefore, is not a true reflection of needs.

An analysis by the Overseas Development Institute (ODI) points out that this leaves NCQG negotiators relying on various calculations by NGOs, management consultancies and research groups “undertaken under different contexts, for possibly different objectives and with different mandates”.

Despite this lack of clarity, negotiators have converged around the need for trillions of dollars to deal with climate change. But arriving at a more precise figure for the NCQG has proved difficult, in part because countries do not agree on what it is supposed to include.

Developing countries prefer a target made up largely of public funds from developed countries. Meanwhile, developed countries have proposed targets covering a much larger range of sources and including “global investment flows”, rather than public money given by developed countries to developing ones alone. (See: What sources of money should be included in the NCQG?)

As a result, Iskander Erzini Vernoit, director of the Imal Initiative for Climate and Development, tells Carbon Brief that, “while all parties are talking about trillions, they are doing so in entirely different ways”.

Developing country groups, including the Like-Minded Developing Countries, the Arab Group and the African Group, have proposed a few ideas for climate finance targets, all in the region of $1-1.3tn a year, as the chart below shows. Pakistan has proposed the highest figure so far – “a minimum of $2tn” – but it has not specified the timeframe.

Meeting such a target would require an unprecedented tenfold boost in climate finance by 2025. (However, it is difficult to compare like-for-like, as countries have different expectations about the sources that will make up the NCQG target.)

After years of developed countries struggling to hit the relatively modest $100bn goal, these new demands raise the issue of plausibility.

Major contributors including the UK, France and Sweden have all slashed their aid budgets in recent years, reducing the pool of public finance available.

Meanwhile, the US has consistently underperformed in providing climate finance. This is despite most analyses indicating that it should be by far the largest contributor, as it is the world’s richest country and the biggest historic contributor to climate change.

Jonathan Beynon, a senior policy associate at the Center for Global Development, tells Carbon Brief:

“Public budgets are under pressure in most developed countries, prospects for such massive increases in climate finance look limited, however justified they might seem.”

Developed countries stress the need for a “realistic” NCQG target. In one statement, the US mentions the annual needs of developing countries exceeding $1tn a year, but says “it is clear that public international finance alone cannot reach such levels”. It adds:

“There is a fine line between a support goal that stretches contributing parties and one that is so unrealistic that it actually diminishes incentives and potentially undermines the Paris Agreement process.”

Furthermore, the US argues that developed countries do not have to meet the “totality of needs” in developing countries, noting that the NCQG mandate only requires parties to “tak[e] into account” these needs.

Developed countries have largely resisted suggesting a numerical target for the NCQG. They argue that a specific amount cannot be agreed upon until a decision is made on who will contribute towards it. The US has only gone so far as to restate that the goal should be “from a floor of” $100bn per year – as already set out by the Paris text.

(Experts have noted that the $100bn goal should be corrected for inflation, at the very least, which would add many billions of dollars. Beynon says “inflation and economic growth alone” would allow “perhaps a doubling by 2035”.)

Another developed-country proposal from the EU mentions a goal of $2.4tn annually by 2030, a number identified by the Independent High-Level Expert Group on Climate Finance – a group of economists tasked with working out the “investment” needs in developing countries.

In the expert group’s proposal, just $150-200bn per year would come directly from other countries, with $1.4tn from the domestic resources of developing countries themselves.

Alex Scott, a senior associate in climate diplomacy at the thinktank ECCO, noted in a recent briefing that progress outside negotiations, such as mobilising more climate finance from the World Bank, could “build a bit more confidence amongst developed countries that…there are other sources of finance that are going to complement what they can put on the table”.

One recent assessment by a team of NGO climate-finance analysts concluded that a “business-as-usual” scenario could result in $173bn of climate finance being provided and mobilised by 2030 – a 50% increase from 2022 levels. This is based on existing pledges by developed countries and planned reforms to multilateral institutions.

Others in civil society point to the trillions spent on Covid-19 and the war in Ukraine, and the trillions that could be raised by taxing fossil fuels and billionaires. Meena Raman, head of programmes at the Third World Network, tells Carbon Brief that the unwillingness of developed countries to commit to more funding is a failure of “political will”:

“It’s very dubious when you say you have not got enough money for climate, but you see that there is a lot of money for bombs and wars.”

Which countries will contribute to the new target?

One of the most contested topics in NCQG negotiations is whether to expand the list of countries that must provide climate finance.

Global-north nations broadly want relatively wealthy, emerging economies, such as China and the Gulf states, to start contributing officially under the UN climate regime. Developing countries argue that, after failing to meet their climate-finance targets, developed countries are trying to shift their responsibilities.

As it stands, only 23 countries are obliged to provide climate finance, including western Europe, the US, Japan, Australia, Canada and New Zealand. The EU must also provide climate finance, independently from the funds provided by its member states.

This group, listed in “Annex II” of the UNFCCC, is based on the membership of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) in 1992. (OECD member Turkey secured removal from Annex II in 2001, on the basis that it was an emerging economy.)

The world has changed a lot in the three decades since the contributor list was agreed.

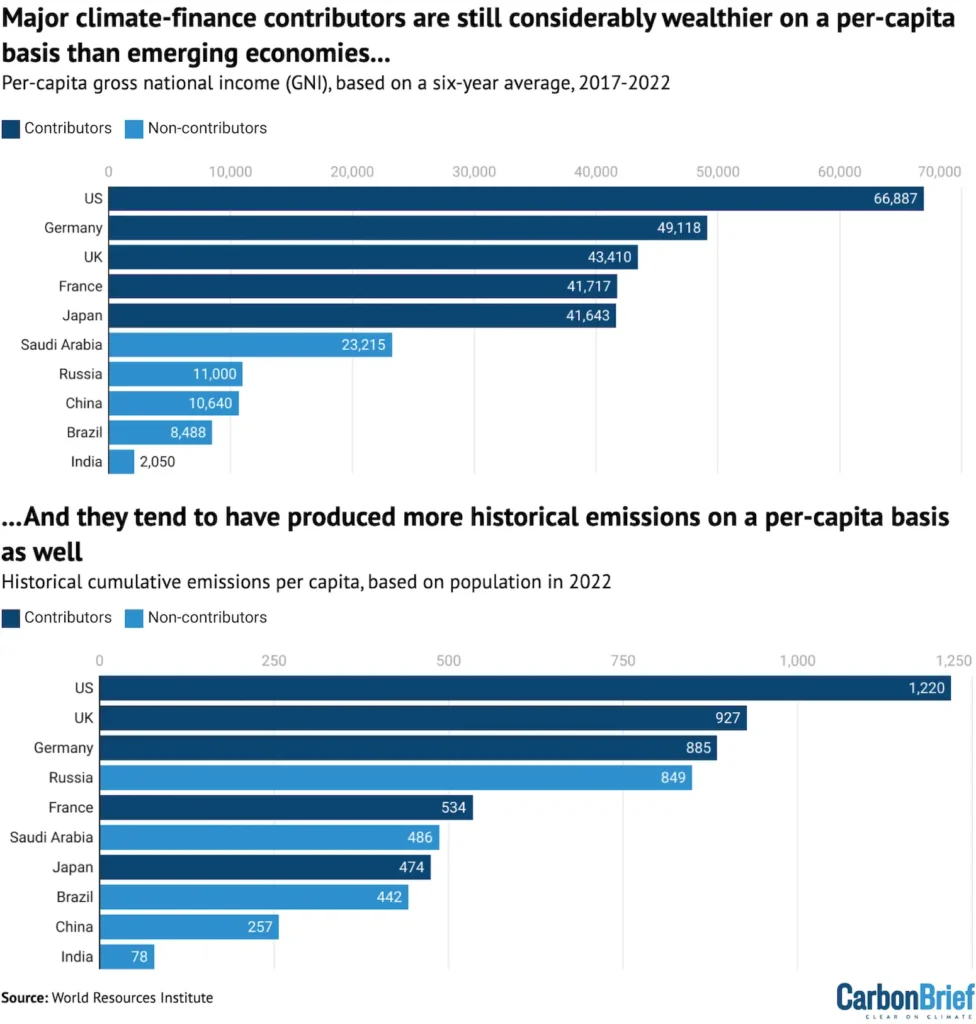

As the chart below shows, emissions from non-Annex II countries, particularly China, have increased significantly since 1992. Many of these nations are also wealthier, and both of these factors are frequently cited as reasons for such countries to start paying climate finance.

There have been consistent efforts by donor countries to broaden the pool of climate finance providers. Indeed, the language in the Paris Agreement reflects this, saying that “other parties” are “encouraged to provide” climate finance “voluntarily”.

However, the division between countries “obliged” versus “encouraged” to contribute has remained. Only Annex II countries were responsible for delivering the $100bn goal.

Developed countries are clear that bringing more donors on board for the NCQG is a priority for them. In a submission ahead of negotiations, the EU refers to “evolving” responsibilities and abilities to pay. It states that:

“The collective goal can only be reached if parties with high greenhouse gas emissions and economic capabilities join the effort.”

The US says that, in its view, agreeing to renegotiate the climate-finance target from 2025 was done on the basis of considering new contributors, making this topic “entirely legitimate, indeed appropriate”.

Developing countries, on the other hand, are firmly opposed to any changes. They argue that it is beyond the legal mandate of the NCQG.

The G77 and China group of 134 developing countries stresses that the NCQG falls under the Paris Agreements and the UNFCCC. Therefore, it includes the principle of “common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities” (CBDR-RC).

In this case, CBDR-RC refers to developed countries’ obligation and capacity to provide climate finance to developing countries. This principle is “not negotiable” and the NCQG mandate “does not include any discussions on modifications” to climate treaties, the G77 and China group says.

There is no agreed-upon way to determine how responsible countries are for causing climate change, and how much they should be helping to prevent it. This makes determining who could or should contribute to an expanded donor base complicated.

The table below, which draws on a recent paper led by Dr Pieter Pauw of Eindhoven University of Technology, shows various metrics that have been considered to identify new donors for the NCQG.

These include how countries are identified under various international treaties, measures of emissions and wealth, membership of powerful institutions and willingness to contribute to global development funds.

There are 50 non-contributor countries that tick two or more of these boxes, with a handful of relatively wealthy or large nations scoring the highest. (As with any attempt to identify new contributors, this ranking relies on subjective criteria. It scores all of these factors equally without making a judgement of how important they are, and countries are ranked in the order they appear in the study).

Most proposals for identifying new contributors consider a country’s ability to pay – measured using gross national income (GNI) – and its responsibility for climate change, often based on historical emissions. Nations such as Canada and Switzerland have proposed a new system for determining climate-finance donors, based on this kind of data.

Yet different versions and combinations of these metrics can yield very different results. Focusing on total emissions and economic status generally throws up a selection of large, emerging economies, including China, India, Russia and Brazil.

However, many analyses include some variation of per-capita emissions and income, to ensure a “fairer” representation that does not penalise countries with large populations.

Such calculations suggest that small, wealthy fossil-fuel producers, including the United Arab Emirates, Qatar and Kuwait, and small, high-income nations, such as Israel, South Korea and Singapore, should contribute to climate finance.

But outcomes can vary significantly, even when accounting for per-capita measures. The best example of this is China, which is the consistent focus of developed-country efforts to expand the contributor list.

Some assessments identify China as an obvious candidate for future contributions – and one that could make a big difference to total spending. Analysis by the Centre for Global Development (CGD) suggests, based on methods that take per-capita metrics into account alongside other factors such as aggregate GNI, that China should contribute up to around 7% of climate finance.

However, if comparability with Annex II countries is considered important when measuring per-capita historical emissions and income, as in analysis by the thinktank ODI, the results are very different. China still ranks far below any of the current developed countries that provide climate finance on these measures.

In fact, the charts below, based on WRI figures, show that major climate finance contributors still largely surpass emerging economies on both per-capita historical emissions from fossil fuels and industry, and per-capita GNI. (These rankings remain roughly the same if land-use emissions are included, although Russia rises higher in the list.)

Given this, the ODI concludes in its analysis that demands for China to become a contributor have “dubious” scientific basis and are “based on geopolitics, particularly China’s status as global power and international financier”.

All of this is further complicated by the fact that many relatively wealthy countries that are not obliged to provide climate finance, including China and South Korea, already contribute climate-related aid and other funding that could be classified as climate finance.

Yet there is resistance from nations such as China to formally classifying their activities as “climate finance” under the UN. Doing so could result in them facing more scrutiny and accountability.

It could also have great political significance given the long-standing division between “developed” and “developing” states in UN talks. This “firewall” was partially broken down with the Paris Agreement, which compelled all countries to set their own “nationally determined contribution” to climate action, but has remained in place for climate finance.

Charlene Watson, a senior research associate at the ODI, says developed country officials argue that having more countries on board makes it easier for them to persuade their treasuries to release more climate finance. However, she questions the value of insisting countries that already provide climate-related funds are included in the UN system:

“My view is that the cake is not going to get any bigger in the short term. It’s just going to be that we can better see the size of the cake.”

Pauw says there is a need for more nuance, including a new category of “net recipients” that both give and receive climate finance. He says coming up with a new list of contributors may be too difficult:

“Whatever you push forward as an idea is arbitrary. There will always be countries who say ‘we cannot agree to this’ – which means that you will not reach agreement.”

One compromise that has been proposed is to introduce different contributor bases for different “layers” of the NCQG, if countries agree on a “multilayered” goal.

That way, China and others might not be responsible for contributing to the “new $100bn” part of the goal, but may be covered by another layer. (See: What sources of money should be included in the NCQG?)

Meanwhile, Erzini Vernoit says poorer developing countries are “extremely wary” of the contributor base discussions, as any ambiguity over who is obliged to provide climate finance could hamper its provision. “Accountability is why burden-sharing frameworks and differentiated lists, like the Annex II list, are important to poorer recipient countries,” he explains.

What sources of money should be included in the NCQG?

Another highly contentious issue in the NCQG negotiations is what types of finance should feed into it. This inevitably influences the discussion of how big the goal could be.

The $100bn target is already fairly broad, covering finance “from a wide variety of sources, public and private, bilateral and multilateral, including alternative sources of finance”.

This in itself is controversial, with civil society groups and developing countries often arguing that the goal relies too much on low-quality finance, such as non-concessional loans. Nevertheless, the NCQG has the potential to be even broader.

Developed countries argue that expanding the scope, with a focus on private investment and gearing the entire financial system towards climate action, is the only way to raise the trillions of dollars of money required.

These wealthier nations generally want the goal to be “multilayered”, with a large outer layer consisting of “global investment flows for climate action”. The framing is important, as it could refer to all kinds of money being spent everywhere – not only in developing countries – including investments made by the developing countries themselves.

The developed nations also propose a smaller sub-goal within this investment layer, more aligned with traditional “climate finance”, which consists of finance “provided” and “mobilised” for developing countries.

(Here, “provided” is understood as referring to climate finance given by one country to another, while “mobilised” refers to private investment that comes as a result of public money “de-risking” investments and getting projects off the ground.)

This approach could make a big difference to how much money these countries would be obliged to provide. For example, an EU submission describes an “investment” goal in the trillions, in contrast to a “provided and mobilised” goal in the billions.

In addition, developed-country statements have stressed the “important role of the private sector”, the need for “reforming the multilateral financial architecture to further unlock climate finance” and the role of “innovative financial instruments” to raise more money.

By contrast, many developing countries have argued for a single goal that channels high-quality climate finance from developed countries to them in a reliable way.

In practice, this means developing countries want as much of it as possible to come in the form of grants from developed countries’ public coffers. The Arab Group has suggested that at least $441bn of the $1.1tn in annual climate finance it has proposed should come from developed-country grants.

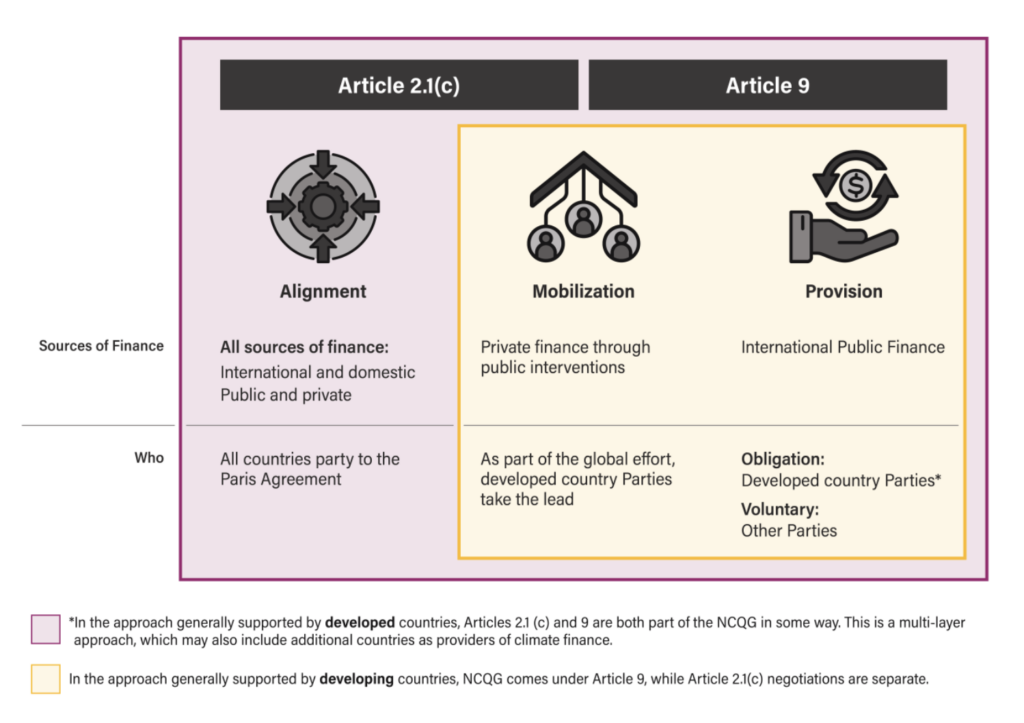

All of this speaks to a central tension about the significance of two articles in the Paris Agreement. Article 9 states that developed countries are obliged to provide climate finance to developing countries and others are encouraged to do so voluntarily. Article 2.1c, meanwhile, calls for all “financial flows” to be aligned with the agreement’s goals.

As the WRI diagram below shows, developing countries want to keep the NCQG talks focused on Article 9, whereas developed countries say both articles should be covered. Developed countries, such as Japan, have said that they think Article 2.1c also justifies expanding the contributor base. (See: Which countries will contribute to the new target?)

Pauw of Eindhoven University of Technology tells Carbon Brief that this comes down to a fundamental difference of opinion on what climate finance is and should be.

On the one hand, the world needs to channel as much money as possible into tackling climate change and, on the other hand, there is the question of transferring money from developed to developing countries – often framed using the language of climate justice. He says:

“You can’t mobilise a lot of money if you provide everything in grants. So those two motivations seem to clash, and it’s important to understand that both of them are relevant, both of them are important and both of them need to be realised.”

The wording below from the proposed “draft negotiating text” released ahead of the COP29 negotiations shows the main options on the table for the NCQG.

Option 1 broadly captures ideas proposed by developing countries, while option 2 captures the layered “annual investment goal” presented by developed countries.

There are practical reasons for developing countries wanting to avoid certain types of finance in the NCQG.

Some global-north leaders have framed private finance as essential for meeting the needs of developing countries. For example, when asked about climate finance, former US climate envoy John Kerry repeatedly stated that “we don’t have the money”, arguing that the key would be to encourage more private capital into climate-related activities.

Yet the amount of private climate finance “mobilised” by developed countries remained virtually unchanged at around $14bn each year between 2016-2021, only increasing significantly to $22bn in 2022. (This is based on OECD data for private finance with a clear causal link to a donor country sending development finance to a project.)

Private investment is also far less likely to flow into the poorest countries, many of which are the most in need of climate finance. It is often viewed as unsuitable for many climate-adaptation projects, which are less likely to generate profits than mitigation work such as clean-energy projects.

Moreover, while national governments are within the remit of the UNFCCC and the Paris Agreement, private companies and other financial actors, such as banks, are not. This could make it more risky to rely on them to meet the NCQG.

There are also strong calls from many developing countries to exclude “non-concessional” loans – provided at or near market rates – from climate finance altogether.

Since 2016, around 70% of public climate finance has been delivered in the form of loans, with Japan, France and Germany, as well as MDBs, providing most of their contributions in this way.

UN figures suggest that at least one-fifth of reported loans are “non-concessional”, resulting in wealth flowing back to the donor countries as loan repayments and interest, according to a Reuters investigation.

Many of the poorest countries are spending more on servicing debts than they receive in climate finance, according to the International Institute for Sustainable Development.

These debates form part of a wider discussion around the “quality” of finance.

Developing countries want finance to be predictable and accessible, especially given the complications they often face when obtaining it from MDBs and large funds.

For their part, developed countries are more likely to emphasise the need for “effective” climate finance – meaning funds that are used for their intended purposes and have a climate impact.

What kind of activities will the NCQG support?

Finance for climate action is divided into broad categories, depending on its main purpose. The $100bn target supports two types of activities: those that cut emissions – mitigation; or those that help countries adapt to climate change.

Now, there is pressure from most developing countries to include loss and damage as a “third pillar” in the NCQG. This would enshrine support for the victims of climate disasters as an official component of the international climate finance goal, for the first time.

After years of fraught negotiations, developing countries secured a “win” last year with the launch of the loss-and-damage fund at COP28.

However, contributions to the fund have been small compared to the scale of climate-related damages, which are estimated to reach $447bn-894bn per year by 2030.

Some developing countries would like to see NCQG sub-goals in order to ensure there is ring-fenced funding available for adaptation – which remains poorly resourced compared to mitigation – and for loss and damage. This would involve percentages of the overall target being assigned to each of the three pillars.

Sherri Ombuya, a consultant at Perspectives Climate Group, tells Carbon Brief that there has been some convergence between parties on the general idea of increasing adaptation finance. “This builds on some existing positions that have already taken place within the broader negotiation space,” she says.

(Developed country parties have already pledged to double adaptation finance from 2019 levels by 2025, for example.)

However, developed countries broadly do not want to incorporate loss and damage under the NCQG. They argue that, while a fund for loss and damage finance has now been established, contributions to it are voluntary and not part of the NCQG mandate.

Moreover, Article 9 of the Paris Agreement only refers to climate finance for “mitigation and adaptation” – and the Paris “decision text” that mandates the NCQG does the same.

Developing countries argue that including loss and damage in the NCQG is nevertheless valid, because Article 8 of the Paris Agreement separately “recognises” the importance of “averting, minimising and addressing” loss and damage.

They also see room for the climate-finance goal to expand over time, to reflect the changing needs of developing countries, in line with the Paris Agreement requirement that “efforts of all parties will represent a progression over time”.

How long will countries have to meet the NCQG?

Parties at COP29 must also agree on the timeframe for the provision of climate finance under the NCQG, as this was not specified in Paris.

A key source of conflict concerns whether the target should cover a shorter period of around five years or a longer one of 10 years or more.

Some developing party groupings, including the LMDCs and the Arab Group, have expressed a preference for a five-year goal covering the period from 2025-2030, with the same amount of money – roughly $1tn – provided every year.

An advantage of having a shorter timeframe could be that it gets money moving faster. Supporters also stress the importance of a “revision” or “review” process once the five years are up, in order to adequately reflect “the evolving needs of developing countries”.

Other developing countries, including AOSIS and the Least Developed Countries (LDCs), have supported a 10-year timeframe, but with some kind of review after around five years.

Some parties and civil-society groups have pointed out that a five-year timeframe aligns with existing processes for monitoring progress under the Paris Agreement.

Both the global stocktake and national climate plans – known as “nationally determined contributions” (NDCs) – run on five-year cycles and could, therefore, feed into a review of the NCQG goal.

In an assessment of the NCQG, the World Resources Institute (WRI) notes that, while there are advantages to revisiting the target, “reopening negotiations on the NCQG during revision cycles has the potential to cause additional delays and complexity”.

Meanwhile, developed countries including Switzerland and the EU favour a 10-year timeline.

Notably, they have suggested that the NCQG will be achieved “by 2035”. This leaves room to gradually scale funding up over time rather than achieving it up from 2025 onwards, meaning less immediate pressure on contributors.

How will progress towards the target be reported and tracked?

There is general agreement that a workable NCQG requires a system where governments and other institutions report their climate finance transparently. Only then can progress towards the goal be tracked – and contributors held accountable.

As it stands, there are fundamental gaps in the system for tracking climate finance.

Despite being agreed upon in 2009, there was no official UN system in place to track progress towards the $100bn goal until the Standing Committee on Finance (SCF) was tasked with doing so in 2021 – one year after the goal was supposed to have been delivered.

This does not mean that no one has been reporting climate finance. Developed countries have to produce reports for the UNFCCC every two years, which must include the finance they have channelled into developing countries, both directly and through multilateral institutions.

Developed countries also submit information about climate-related spending to the OECD, which publishes its own assessments of climate-finance progress. (In addition, the OECD served as the de facto tracker of progress towards the $100bn goal.)

Meanwhile, NGOs – particularly Oxfam – have produced regular analyses of climate finance.

Crucially, these assessments arrive at very different estimates of how much climate finance has been provided to developing countries. This is partly because there is no widely accepted definition of “climate finance” in the UN climate process.

Nations are allowed to come up with their own definitions of what counts, as well as their own methodologies to track, measure and report it to official bodies. “This results in challenges in aggregating data on climate finance,” according to the SCF.

The lack of clarity around climate-finance figures has contributed to a “continuous erosion of trust between parties in international climate negotiations”, according to one paper.

Real-world implications include governments inflating the amounts they have given and labelling questionable funding for everything from coal to hotels as climate finance.

So far in the NCQG discussions, there has been a broad consensus that the enhanced transparency framework (ETF) is the best way to report on progress. The ETF is a system set up under the Paris Agreement, which requires most parties to submit information about their climate progress in biennial transparency reports (BTR) from the end of this year.

However, the ODI’s Watson tells Carbon Brief that even if this is agreed there will still be plenty to discuss in the NCQG transparency negotiations:

“The ETF just captures reporting from countries…The more we start talking about whether other sources [of finance] count, or how to capture finance from purely private actors, they’re obviously not covered by the BTRs that come out of the ETF. So what else do we need to know?”

These discussions are, therefore, tied to the question of which sources feed into the NCQG and also which countries contribute towards the goal.

Developing countries have fewer reporting obligations under the ETF and there may be pressure on them to report more if the contributor base is expanded, Watson says.

As for tracking the resulting figures, some parties have suggested the SCF should be given this task. Governments may prefer to opt for a UN committee rather than leaving the task to an NGO or external international body, but this may still face opposition.

Finally, despite the apparent convergence between parties on some of the transparency requirements, there is far less agreement on the need to define “climate finance”.

The G77 and China group of developing countries has pushed for such a definition, calling for non-concessional loans and “non-climate specific finance” to be excluded.

Many developing countries stress that climate finance must be defined as “new and additional”, in line with the language used when the $100bn target was set and in the original UNFCCC treaty. This is broadly understood to mean money that comes on top of other obligations.

However, developed countries provide much of their climate finance from their aid budgets and studies suggest that much of this is not “new and additional”.

Given the impact it could have on their finances, developed countries have strongly resisted a strict definition. Perspectives Climate Group’s Ombuya tells Carbon Brief that, while she thinks it is possible that parties could converge on excluding some types of finance from the NCQG, “I feel that to have a successful outcome, it’s likely that parties will have to have a willingness to do without a common definition on climate finance”.