COP21: Five things to look out for in the final Paris text

Sophie Yeo

12.11.15Just after 9pm last night, tired delegates received a fresh draft of the UN climate deal.

Unlike previous iterations, this latest document was free from the myriad options and square brackets that had cluttered previous drafts.

The relatively clean text – down from 367 square brackets to 50 in 24 hours – suggests that, overnight and during the day, nations had managed to make some of the necessary compromises and tradeoffs necessary, and had done so without sacrificing the ambition of the deal.

While some were ready to celebrate this glimpse of success, others warned that everything was still to play for. As Laurent Fabius, the president of the talks, has repeatedly warned: “Nothing is agreed until everything is agreed.”

Talks stretched on through the night, with ministers discussing the crunch issues in small groups. With no solutions in sight by the morning, Fabius — previously insistent that the talks would end by 6pm on Friday — pushed the release of the new text back to Saturday at 9am.

That means today is looking tense and frenzied for the politicians responsible for striking the deal, and slow and lethargic for everyone else at Le Bourget attempting to track the process.

Here Carbon Brief sets out the five key issues to look out for in the final text.

Long-term goal

Long tern goal. Credit: UNFCCC, 10 December.

The current draft of the text has narrowed down the various options for a long-term goal to just one: a peaking of greenhouse gas emissions “as soon as possible”, and greenhouse gas emissions neutrality in the second half of the century.

This lacks the specificity of some of the options in the previous draft, including the option to reduce emissions to 70-95% below 2010 levels by 2050, and there are many who would like to see these numbers back in the text.

Nonetheless, it is stronger than another previous option of “climate neutrality” — a vague and unusual term, whose sudden appearance had experts rallying to come up with a definition.

This is closely tied to the long-term temperature goal. The text says that global temperatures should be held to “well below 2C” and “pursue efforts” to hold it below 1.5C. Obviously, the lower the better, and small island states in particular have pushed for 1.5C to replace 2C as the absolute goal.

Ambition

Ambition. Credit: UNFCCC, 10 December.

Whatever countries agree this week in Paris won’t mean much at all unless there is a clear mechanism to scale up ambition over time.

This will be achieved through a review-and-ratchet process, as Carbon Brief explained last week. This is a complicated melange of dates, cycles and stocktakes, spread across both the agreement and the decisions.

But the basics come down to this. Will there be an opportunity to examine and update the current round of INDCs before 2020? When will the next review take place? How often will countries have to submit new INDCs?

Currently, the text says there should be a review in 2019, 2023 and every five years thereafter. It also asks countries to update or submit a new INDC in 2020. These features provide a strong foundation, but the fact that it remains scattered throughout the text is unhelpful.

Differentiation

Differentiation. Credit: UNFCCC, 10 December.

Differentiation comes in many guises. One of the most controversial is mitigation, or how countries will tackle their emissions.

Some of the most heated exchanges of the negotiations have been reserved for the topic, as countries argued over whether obligations should be based on the old 1992 division of developed and developing countries, or whether it should include a dynamic system able to reflect real world changes.

The draft text suggests that countries supporting the latter option have prevailed, with the deal pushing for a common system that countries will adopt over time as their capacities permit. But could the alternative once again rear its head before the deal is finally closed?

Finance

Finance. Credit: UNFCCC, 10 December.

Square brackets — once commonplace and now rare — continue to litter the section of the agreement dealing with finance. What sort of money should developed countries have to provide? Will it be new? Additional? Adequate? These, and more, are all options that remain in the text.

The question over whether to expand the donor base of climate finance has hovered consistently over the talks. Should developing nations also face pressure to provide climate finance? The draft has suggested they should provide it on a “voluntary, complementary basis” — wording which has been supported by the US, but is unlikely to be strong enough for the EU, and has been something of an anathema to the powerful G77 alliance of developing countries. Could there be a last-minute clash of these titans?

Other defining features in the current draft include the inclusion of the $100bn pledge as a “floor” for future finance provisions, short-term quantified goals, and a review. All of these add to the ambition of the current text.

Loss and damage

Loss and damage Option 1. Credit: UNFCCC, 10 December.

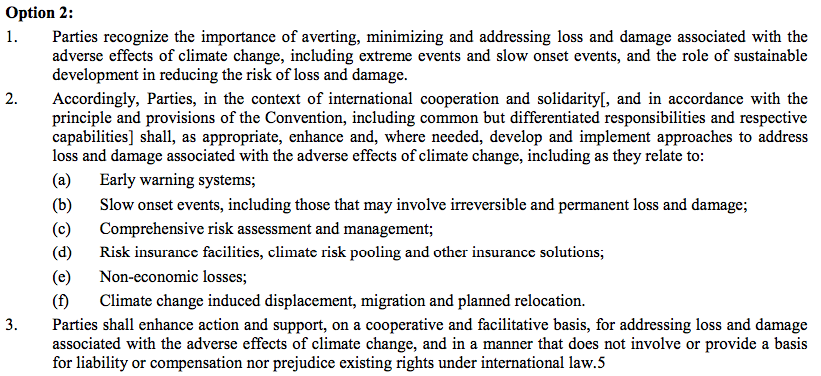

Loss and damage Option 2. Credit: UNFCCC, 10 December.

Loss and damage is the issue of how countries deal with the impacts of climate change to which countries cannot adapt. This has remained static at the centre of the various iterations of the draft text, as changes have eddied around it.

No more. While other issues now look close to resolution, this issue has now exploded into a maelstrom of options.

The most controversial of these is at the beginning of the Article. The first option presents a very simplistic reference of loss and damage. The second sets out a detailed workplan akin to what many developing countries are seeking. But it comes with a bitter pill: the exclusion of any possibility of liability or compensation from developed nations for the part they played in causing climate change (it doesn’t exclude this arising from other international treaties, though).

It’s also worth looking out for where this section appears in the final text. Will it have its own article, or appear under adaptation? Some consider this a symbolic issue, but it is important to many vulnerable nations as it bestows greater political significance.

And finally…

While these are likely to be the crunch issues in the final hours, there are a number of other things worth keeping an eye on.

“Entry into force” is buried in Article 18, but could have a big impact. In its current state, it requires 55 parties accounting for either 55% or 70% of emissions to ratify the agreement before it comes into force. This means that a few large emitters teaming together potentially have the power in their hands to delay or even scupper the deal.

Counting up the number of “shalls”, “shoulds” and “invites” in the final text will also give an important overview of the strength of the text. If the text says that countries “shall” do something, this makes it legally binding. The word currently appears 164 times.

With talks set to go on all night, there is one final obstacle that those leaving Le Bourget conference centre should look out for. Sleeping delegates, campaigners and journalists littering the halls provide one final chance to trip up as the 2015 Paris talks come to a close.