COP16: Tracking country pledges on tackling biodiversity loss

Multiple Authors

05.02.24At the COP15 biodiversity summit in December 2022, nearly every country in the world committed to a new global agreement to “halt and reverse” biodiversity loss by 2030 and “restore harmony with nature” by 2050.

Under the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF), countries pledged to release new national plans for how they will achieve a range of goals and targets.

These plans are known as national biodiversity strategies and action plans (NBSAPs).

The GBF requires countries to submit new NBSAPs ahead of COP16, the next global biodiversity summit being held in Cali, Colombia in October.

Below, Carbon Brief tracks which countries have submitted new NBSAPs and analyses how each country has pledged to meet the key targets outlined in the GBF.

This piece was updated on 10 June to add data from Austria and Uganda, on 25 July to add Canada, Italy and Suriname, on 22 August to add Malaysia, on 23 September to add Mexico, Cuba, Burkina Faso, South Korea, Afghanistan and Indonesia, on 14 October to add Jordan, Malta, Tongo, Australia, the United Arab Emirates and Slovenia and on 25 October to add Colombia, Denmark, Mauritania, Aruba, Curaçao, Libya, Moldova, Palestine, Uganda, Tunisia and Norway.

Table design by Tom Pearson. NBSAP translations by Anika Patel, Yanine Quiroz, Alice Vernat-Davies and Anastasiia Zagoruichyk. A full spreadsheet of this data is available to view. Please note that the Convention on Biological Diversity has made changes to its database ahead of COP16, which has affected access to some links.What are NBSAPs and why are they important for global action on nature loss?

NBSAPs are blueprints for how individual countries plan to tackle biodiversity loss within their borders, as well as ensure they meet the international targets outlined in the GBF.

Each country that is party to the UN’s Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) is expected – but not legally required – to submit NBSAPs.

There are 196 parties to the CBD including the EU. This includes every country of the world except the US and the Holy See, the governing body of the Vatican. (Republican lawmakers have blocked the US from joining the CBD, citing concerns over “American sovereignty” and “financial burdens”.)

Under the GBF and its underlying documents, countries agreed to submit updated NBSAPs ahead of COP16, which is scheduled for 21 October to 1 November 2024 in Colombia.

NBSAPs are similar to nationally determined contributions (NDCs), plans that outline how individual countries envisage meeting the goals of the Paris Agreement. However, a key difference is that countries are legally obliged to submit NDCs, but not NBSAPs.

(The Paris Agreement is an international treaty agreed in 2015 aimed at keeping global temperatures well below 2C, with an ambition of limiting them to 1.5C, by the end of the century.)

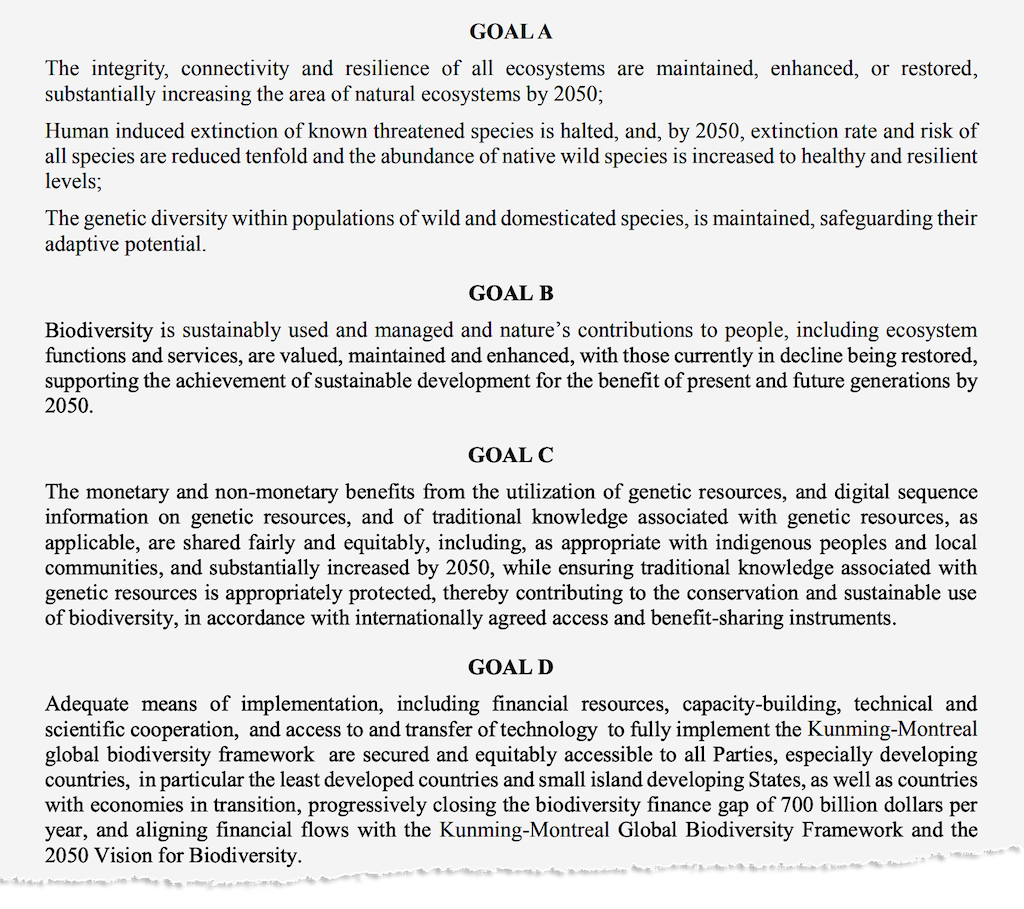

The GBF contains a set of four goals and 23 targets, which collectively aim to reverse the rapid decline of biodiversity by 2030 and “restore harmony with nature” by 2050.

One of the most publicised targets is target 3, which commits countries to protecting 30% of their land and seas for nature by 2030 (commonly known as “30 by 30”). The full list of targets is included below.

| Target | Description |

|---|---|

| 1 | Effective management of land- and sea-use change, loss of highly important biodiverse areas close to zero by 2030 |

| 2 | Effective restoration of 30% of degraded ecosystems by 2030 |

| 3 | Effective conservation and management of 30% of land and 30% of oceans by 2030 |

| 4 | Halt human-induced extinctions and maintain and restore genetic diversity |

| 5 | Sustainable use, harvesting and trade of wild species |

| 6 | Mitigate or eliminate the impacts of invasive alien species, reduce the rates of establishment of invasive species by 50% by 2030 |

| 7 | Reduce pollution risks and impacts from all sources by 2030, reduce the overall risk from pesticides by half |

| 8 | Minimise the impacts of climate change and ocean acidification on biodiversity |

| 9 | Ensure sustainable use and management of wild species, while protecting customary use by Indigenous peoples |

| 10 | Sustainable management of areas under agriculture, aquaculture, fisheries and forestry |

| 11 | Restore and enhance ecosystem function through nature-based solutions and ecosystem-based approaches |

| 12 | Increase the area and quality of urban green and blue spaces |

| 13 | Fair and equitable sharing of the benefits arising from the use of genetic resources |

| 14 | Integration of biodiversity into policies and development across all sectors |

| 15 | Enable businesses to monitor, assess and disclose their impacts on biodiversity |

| 16 | Encourage sustainable consumption, including by reducing food waste by half by 2030 |

| 17 | Strengthen capacity for biosafety measures and ensure benefits-sharing from biotechnology |

| 18 | Phase out or reform harmful subsidies in a just way, reducing them by $500bn by 2030 |

| 19 | Substantially increase financial resources, mobilise $200bn per year by 2030 from all sources, including $30bn from developed to developing countries |

| 20 | Strengthen capacity-building and technology transfer |

| 21 | Integrated and participatory management, including the use of traditional knowledge |

| 22 | Equitable representation and participation of Indigenous peoples and local communities |

| 23 | Ensure gender equality in the implementation of the framework |

In their NBSAPs, countries are expected to set out how they will work towards achieving these goals and targets.

But while countries are working towards a shared set of goals, each NBSAP will be highly unique. This is because every country has its own unique blend of species and habitats – and its own challenges when it comes to conserving them.

For example, Ireland’s NBSAP speaks about restoring commercial fish stocks in Irish waters to sustainable levels and repairing the nation’s highly degraded peatlands.

By contrast, Japan’s NBSAP talks about ensuring “appropriate distance between human beings and wildlife is maintained”, likely referring to its booming nature tourism industry.

Which countries have submitted NBSAPs?

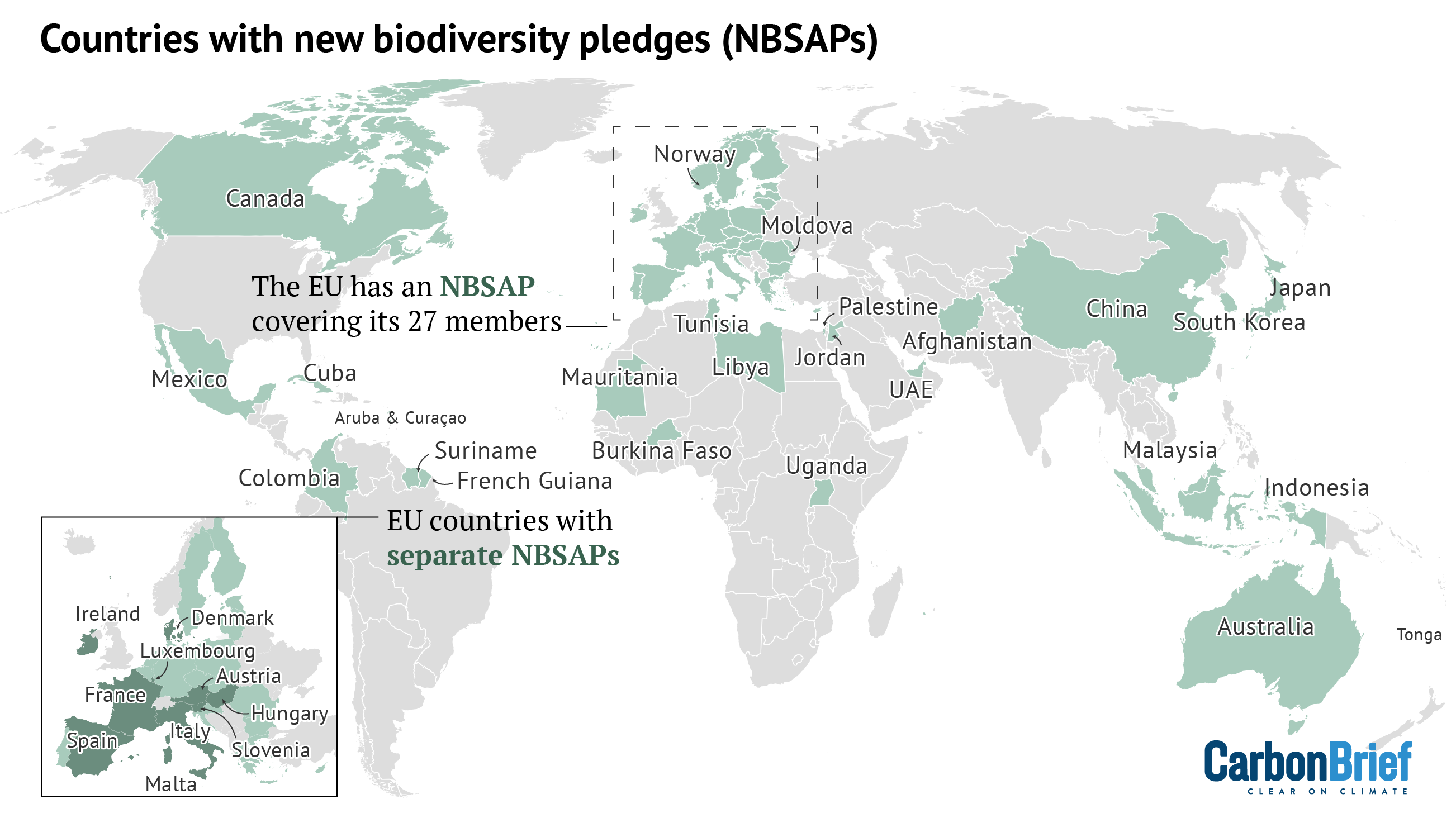

Carbon Brief analysis shows that just 30 countries and the EU met the deadline to submit an updated NBSAP ahead of COP16.

Since then, a further five countries have published new NBSAPs, including COP16 host Colombia.

That leaves 162 parties that are yet to submit updated NBSAPs.

(There are 196 parties to the CBD. However, two of the countries that have submitted new NBSAPs, Aruba and Curaçao, come under the umbrella of the Netherlands and so are not parties to the CBD individually. The Netherlands has not yet submitted an NBSAP.)

The map below shows countries that have submitted updated NBSAPs in green.

At the COP28 climate summit in December 2023, the UK indicated that it will release its updated NBSAP by May. However, delays caused by changes of power in the country forced postponements, and the new Labour government now intends to publish it in the new year, as revealed by Carbon Brief earlier this month.

The world’s most biodiverse country, Brazil, has also confirmed it will not publish its NBSAP until “the end of the year or early next year”, according to a joint investigation by Carbon Brief and the Guardian.

Countries that were unable to meet the deadline to submit NBSAPs ahead of COP16 were requested to instead submit national targets. These submissions list biodiversity targets that countries will aim for without an accompanying plan for how they will be achieved.

As of 25 October, 113 parties had submitted national targets.

What are some key takeaways from the updated NBSAPs?

Reversing biodiversity loss

Examining NBSAPs can offer clues into how countries are responding to the targets set out in the GBF – and their views on traditionally contentious issues such as biodiversity finance, Indigenous rights and the sharing of genetic resources.

The headline “mission” of the GBF is to halt and reverse biodiversity loss by 2030.

While many people associate “biodiversity” with iconic species and tropical rainforests, the term actually covers the whole spectrum of Earth’s biological diversity, ranging from the organisation of genes within organisms to the communities of animals and plants that make up ecosystems.

Last year, a group of biologists explained to Carbon Brief that halting and reversing all biodiversity loss by 2030 would be a “huge challenge”, with one expert saying they were “highly doubtful” it was scientifically possible.

Only a handful of the countries that produced NBSAPs ahead of COP16 explicitly reference the mission to halt and reverse biodiversity loss by 2030.

This includes China, who held the presidency for COP15, and Canada, which acted as the host nation for the conference due to Chinese Covid-19 restrictions – as well as South Korea, Jordan, Australia and Malta.

The EU and some of its member states, such as Ireland and Luxembourg, did make a reference to halting and reversing the loss of pollinators, a target set out in the EU biodiversity strategy.

France’s plan says that it will aim to reverse the decline of “threatened flagship species, especially endemic species in overseas territories”.

All of these references are a far cry from reversing the loss of all biodiversity.

Invasive species and pesticides

There are some areas of convergence among the very small number of countries that have released updated NBSAPs.

Target 6 of the GBF is to “mitigate or eliminate the impacts of invasive alien species” and to “reduce the rates of establishment of invasive species by 50% by 2030”.

The EU, China and Japan all mention targets to reduce the impact of invasive species.

However, there are differences in what the targets aim to achieve. For example, EU nations are targeting a 50% reduction in the number of Red List species threatened by invasive alien species, whereas China and Japan are targeting a 50% reduction in the rate of invasive species establishment.

Target 7 of the GBF is to “reduce the overall risk from pesticides by half”. (It is worth noting that some parties wanted a more ambitious target to reduce the use – rather than the risk – of pesticides by half.)

In its NBSAP, the EU references a target whereby “the risk and use of chemical pesticides is reduced by 50% and the use of more hazardous pesticides is reduced by 50%”.

This wording is repeated in the NBSAPs of many of its member states – so far, Ireland, France, Luxembourg and Spain.

By contrast, Japan references a need for a “reduction in risk-weighted use of chemical pesticides”, while China commits to “reduce” pesticides and to “gradually phase out highly toxic and high-risk pesticides”.

Biodiversity finance

When it comes to the topic of developed nations providing more finance to help developing nations protect biodiversity – one of the most contentious issues at COP15 – there is little consistency among NBSAPs.

Japan makes the clearest pledge when it comes to supporting developing nations, with a target that says the country will aim to ensure “financial resources for the conservation of biodiversity are secured to improve biodiversity global finance gap”.

Japan will also aim to ensure that “capacity-building…in developing countries by Japan’s support are further implemented”.

Ireland also mentions a target to “strengthen the inclusion of biodiversity in international diplomacy and financing”.

In addition, Japan makes reference to target 18 of the GBF, which is to “phase out or reform harmful subsidies in a just way, reducing them by $500bn by 2030”. (“Harmful subsidies” refer to those that prop up industries known to harm nature, such as large-scale meat farming and fossil-fuel extraction.)

Japan says it will “consider” the “identification and reforms of subsidies harmful for biodiversity”.

Spain has a more clear target for subsidy reform, stating:

“By 2025, 50% of identified harmful subsidies will be reformed, redirected or eliminated and ensure that by 2030 all subsidies or incentives are neutral or positive for natural heritage and biodiversity and adequately incorporate environmental externalities.”

Indigenous rights

Clear inclusion of the role of Indigenous people in protecting biodiversity and the need to respect their land rights was one of the biggest issues during the negotiations for the GBF.

In its NBSAP, COP15 host nation Canada devotes lengthy sections to recognising the role of Indigenous people in protecting biodiversity and land in Canada and acknowledges that federal-level policies must include Indigenous knowledge.

For example, Canada’s NBSAP says:

“There is no path to achieving our 2030 targets without the expertise and leadership of First Nations, Inuit and the Métis Nation, and transformative change must centre bold, Indigenous-led measures.”

Another country to reference the role of Indigenous people in its NBSAP is Suriname, which says there is a need to recognise “the collective traditional knowledge and associated intellectual rights of Indigenous and tribal communities”.

A third country to do so is Ireland, which says the role of “Gaeltacht Islands and Island communities in securing and protecting cultural and natural heritage” should be recognised. (The Gaeltacht Islands are three regions of Ireland where Irish Gaelic is the predominant language.)