Climate change could cut growing days of plants and crops by 11%

Robert McSweeney

06.11.15Robert McSweeney

11.06.2015 | 10:45amThe number of days each year when conditions are suitable for plants to grow could fall as the climate warms, according to new research.

Researchers in Hawaii found rising temperatures and falling soil moisture could curtail growth of plants and crops across much of the tropics. And if emissions remain unchecked, gains in plant growth at higher latitudes won’t make up for these losses.

But other scientists, not involved in the study, tell Carbon Brief the new research may have overestimated the negative impacts of climate change.

Plant growth

Climate change is likely to have both positive and negative impacts on plant growth.

A warmer, more carbon-rich atmosphere could provide better conditions for growth. On the other hand, rising temperatures could make conditions too hot for plant growth. How much water and nutrients plants and crops have access to will also affect how much they can grow.

Scientists have conducted numerous studies into how these factors are likely to play out for different plants and different regions of the world.

The new study, published in open-access journal PLoS Biology, takes a different approach. Rather than estimating how much plants might grow, the researchers focus on how many days each year we’ll see conditions favourable for plant growth in the future.

Suitable days

The researchers used satellite data of net primary productivity – a measure of the rate of plant growth – to identify the range of conditions under which plants flourish around the world. Co-author Jamie Caldwell, from the University of Hawaii, explains to Carbon Brief:

We overlaid maps of plant growth with maps of temperature, solar radiation and soil moisture and identified the range of each variable in which 95% of plants currently grow.

The researchers then calculated how many days per year conditions were within this range for all three variables. Conditions aren’t suitable for plants to grow all through the year and all across the world, lead author Prof Camilo Mora, also from the University of Hawaii, tells Carbon Brief:

On average globally, some 120 days are unsuitable to grow plants because of either too cool, such as high latitudes and altitudes, too dry, such as deserts and places with rainy seasons, or not enough sunlight.

The researchers then used averages of global projections for temperature, soil moisture and solar radiation from 14 Earth System Models to calculate how the number of these plant growth days are likely to change by end of the century (2091-2100).

Latitude highs and lows

The researchers examined the outcome of three emissions scenarios used by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change ( IPCC). The maps below show their results for RCP8.5 – the IPCC’s highest emissions scenario.

World map of projected changes in suitable plant growth days from current climate (1996-2005) to future climate (2091-2100) under a high emissions scenario (RCP8.5). Source: Mora et al. ( 2015).

The researchers estimated how the number of suitable growing days is likely to be affected by changes in temperature, solar radiation and soil moisture individually (maps A to C).

They then simulated the impact of changes in two or all three variables together (maps D to H). Areas of blue show increases in suitable days while reds, oranges and yellows show decreases.

In mid- and high-latitude regions, the researchers found the number of days below freezing is likely to fall by up to 7%. This leaves more days each year that are warm enough for plants to grow, giving a boost to overall growth.

You can see from map G above, much of Canada, Russia and China are expected to see increases in plant growth days each year.

At low-latitudes, however, the study finds temperatures could rise above the upper limit for plant growth, leaving fewer days for plants to grow. Map G shows that much of tropics could be affected, particularly Brazil, central Africa and southeast Asia.

Prof Georgina Mace, professor of biodiversity and ecosystems at University College London, who was involved in peer-reviewing the paper, tells Carbon Brief:

There is potentially a markedly more severe impact in tropical areas and in developing countries, placing further jeopardy where there are already significant environmental stresses and rapidly increasing demands.

Of the types of plants and crops the study considered, growth of tropical forests will be most affected by these changes in climate, potentially losing almost three months of suitable growing days each year by 2100, the researchers say.

Emissions scenarios

In addition to the high emissions scenario, the researchers estimated changes when global carbon emissions are substantially curbed ( RCP2.6 and RCP4.5). Under these scenarios, decreases in plants growth days are offset by increases at higher latitudes, they say.

But under the high emissions scenario, the number of suitable growing days worldwide drops by 11% by 2100.

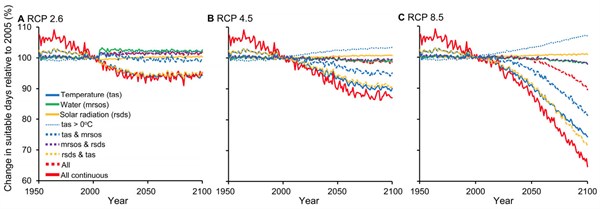

The graphs below show the past and projected changes in global plant growth days from 1950 to the end of the century. The red dashed line shows how growth days could change, taking into account changes in temperature, soil moisture and solar radiation.

Averaged over the whole planet, the changes are small for the low emissions scenarios (RCP2.6 and RCP4.5 – left and middle graphs), but you can see a pronounced decrease after 2050 under RCP8.5 (right graph).

Global average changes in projected suitable days for plant growth from 1950 to 2100, compared to current climate (1996-2005). Source: Mora et al. ( 2015).

However, the fact the researchers use an average across the 14 models could be too simple an approach, says Dr Ed Hawkins, Associate Professor at the University of Reading, who wasn’t involved in the study. He tells Carbon Brief:

This study has taken an overly simplistic approach to using large ensembles of climate simulations, rendering the results highly questionable. The use of a multi-model mean, without quoting the uncertainties, is indefensible. Climate simulations can be used to try and answer the interesting, important and complex questions posed here, but not in the way described.

Narrow ranges

Prof Colin Prentice from Imperial College London, who also wasn’t involved in the study, raises another concern about the limits to plant growth the study uses.

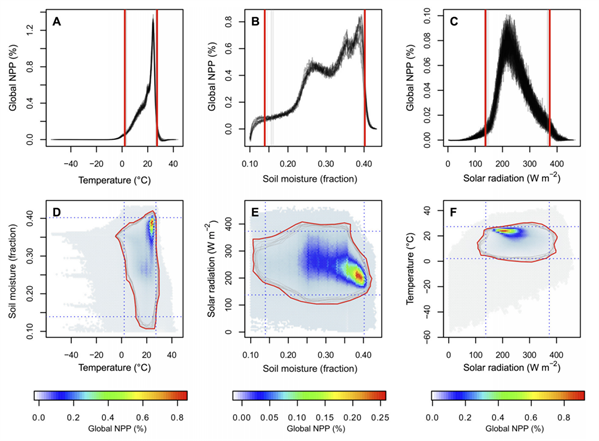

According to the study, 95% of plant growth across the world happens when conditions fall between the red lines in the graphs below. But Prentice tells Carbon Brief this doesn’t mean plants can’t grow outside of these thresholds.

Graphs of global plant growth (net primary productivity, NPP) according to A) temperature, B) soil moisture, and C) solar radiation, and combinations between them in D, E and F. Red lines show the climatic thresholds used in the study. Source: Mora et al. ( 2015).

In real life, we don’t see the sudden drop off in growth at high temperatures and solar radiation that the graphs above show, Prentice says:

[The graphs] do not actually mean that plant growth declines at higher values of temperature and solar radiation. But the higher values of temperature and solar radiation are simply less common in today’s world, in terms of the area they occupy.

In other words, although plants may not grow in certain conditions at the moment, it may be because those conditions don’t occur very often in our current climate, rather than the conditions actually being unsuitable for growth, he says. As a result, the study overstates the negative impacts of climate change on plants, Prentice says.

Nevertheless, although the impact of climate change on plant growth isn’t perfectly understood, it doesn’t mean it won’t a problem, he warns:

Continuing climate change certainly has implications for land ecosystems and plant growth, with likely negative impacts particularly in those climatic regions that are experiencing increasing drought.

The latest IPCC report, for example, says that although crop production in northern latitude countries may benefit from warmer temperatures, it is likely to be consistently and negatively affected in low-latitude countries.

And as this study concludes, the projected impacts of climate change are much reduced under the lower emissions scenarios, underscoring the importance of reducing global emissions to keep risks low.

Main image: Rice paddy and farmer.

Mora, C. et al. (2015) Suitable days for plant growth disappear under projected climate change: potential human and biotic vulnerability, PLoS Biology, doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1002167

-

The number of days each year when conditions are suitable for plants to grow could fall as the climate warms