Climate change ‘a serious threat’ to king penguins, study warns

Robert McSweeney

10.27.15Robert McSweeney

27.10.2015 | 4:16pmIn a new study, published in Nature Communications, scientists reveal how feeding and breeding of king penguins has varied between 1992 and 2010, and how climate change could put a dent in their numbers.

Swimming further and diving deeper

The study focused on the Crozet archipelago in the southwest Indian Ocean, around 3,000km southeast of South Africa. With more than 600,000 breeding pairs, the islands are home to the world’s largest king penguin population.

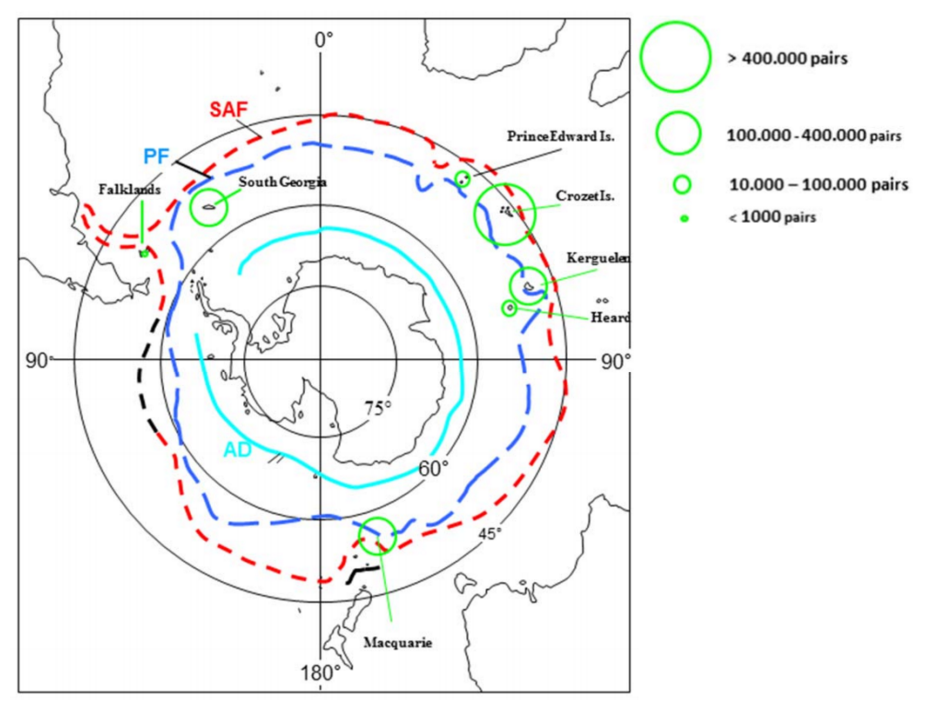

King penguins breed from mid-December to mid-March. When foraging for food to feed their young, the adults swim south towards the fish-laden waters of the polar front, which is typically 300-500km away. This region, shown as a dotted blue line in the image below, is where the cold ocean surrounding Antarctica meets warmer waters further north.

Distribution of king penguin populations around the Southern Ocean – the larger the green circle, the bigger the population. Coloured lines indicate the approximate position of the polar front (blue, dotted), sub-Antarctic front (red, dotted), and Antarctic Divergence (pale blue). Source: Bost et al. (2015).

The position of the front varies from year-to-year with natural fluctuations in the southern Indian and Atlantic oceans. These are, in turn, affected by climate phenomena such as El Niño.![]()

Using satellite transmitters attached to selected breeding penguins, the study tracked their movements between 1992 and 2010. In some years, the researchers found the penguins had to swim further and dive deeper to find food. These years coincided with warmer waters in the southern Indian or Atlantic Ocean, which shifted the polar front southwards.

An increase in ocean temperatures of 1C in the southwest Indian Ocean, for example, pushes the front 130km further south.

In 1997, natural fluctuations conspired to bring “abnormally” warm water to the Crozet islands, pushing the polar front further than scientists had seen before. The satellite tracking showed the penguins had to swim almost twice as far to find food, and dive around 30% deeper.

The extra distance took its toll on the survival of the penguin population, the researchers say. The following year, the number of breeding pairs had fallen by 34%, and took five years to recover to pre-1997 numbers.

While the study looked at natural fluctuations, the findings support previous work that suggests king penguin populations could be negatively affected by climate change. The polar front is projected to shift southwards as ocean surface temperatures warm, increasing the distance that breeding penguins will have to swim to reach food.

Climate change, therefore, represents “a serious threat for penguins and other diving predators of the Southern Ocean”, the new study concludes.

Bost, C. A. et al. (2015) Large-scale climatic anomalies affect marine predator foraging behaviour and demography, Nature Communications, doi:10.1038/ncomms9220