China’s construction of new coal-power plants ‘reached 10-year high’ in 2024

Anika Patel

02.13.25Anika Patel

13.02.2025 | 12:00amA “resurgence” in construction of new coal-fired power plants in China is “undermining the country’s clean-energy progress”, says a new joint report by the Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air (CREA) and Global Energy Monitor (GEM).

The country began building 94.5 gigawatts (GW) of new coal-power capacity and resumed 3.3GW of suspended projects in 2024, the highest level of construction in the past 10 years, according to the two thinktanks.

The accelerated buildout, fuelled by investment from the coal-mining sector, “raises critical concerns” about China’s ability to transition away from the fossil fuel, the report warns.

Analysts expect China’s huge clean-energy capacity additions to slowly squeeze coal’s share of electricity generation, as China works towards its “dual-carbon” goals of peaking carbon emissions by 2030 and reaching carbon neutrality by 2060.

As things stand, rapid coal-power expansion is posing a “challenge” to China’s high-level climate commitments, including on reducing coal use, CREA and GEM argue.

They point to a range of policies that could help China get back on track, including ending new coal plant approvals, as well as power market and grid reform.

Construction fever

Construction started on 94.5GW of new coal-fired power plants in 2024, according to the study. It says this is a sign of continued momentum in developing new coal projects, despite government pledges to “strictly” control the use of the fossil fuel. The report adds that 3.3GW of suspended projects also resumed construction in 2024.

Approvals for new coal construction rebounded in the second half of the year to 66.7GW, after permitting only 9GW in the first half.

Taken altogether, the report says this signals a substantial amount of new capacity will come online in the next few years, “solidifying” coal’s place as a major source of electricity.

As shown in the chart below, China’s new or resumed construction of coal-power plants declined steadily from 84.3GW in 2015 to 32.1GW in 2021. However, it has since risen from 2022, driven by a wave of new projects.

From 2022 onwards, new and revived proposals to initiate coal-power projects also surged, reaching 146GW in 2022 and 117GW in 2023 – well above pre-pandemic levels.

However, the report notes, new proposals fell to 68.9GW in 2024, which could point to “potential cooling in project initiation”. In 2023, China accounted for 95% of the world’s new coal construction.

Meanwhile, retirement and mothballing of old coal plants remains “low”, the report says. This is particularly pronounced in recent years, with the amount of capacity being closed down each year dropping sharply from around 13GW in 2020 to 2.5GW in 2024.

All of this stands in “direct conflict” with Chinese president Xi Jinping’s pledge in 2021 to “strictly limit the increase in coal consumption” between 2021 and 2026, the report says, as well as China’s 2030 carbon-peaking action plan. It adds:

“The policy direction set in China’s updated climate targets for 2035 under the Paris Agreement and the upcoming 15th five-year plan [2026-2030] will be critical to determining the trajectory of China’s coal-power sector and with that, its emissions trajectory.”

This echoes recent analysis published by Carbon Brief.

Fuelled by industry interests

The renewed coal drive is largely being pushed by the mining industry, according to the report, with coal-mining companies increasingly investing in coal-power projects.

More than three-quarters of all newly approved coal power projects were financed by “coal mining companies or energy groups with coal-mining operations”, the study says.

It suggests this may be partly driven by China’s “dual-carbon” goals, which have pushed those companies to diversify in order to “secure stable demand for their output through 2030 and beyond”.

These investments include integrated coal mine-to-power and “pithead” plants, as well as typical coal-fired power plants developed by energy groups with coal-mining operations.

The report notes that many regional coal and energy companies have “intensified” coal-power investments, “aligning their strategies to sustain coal’s dominance at the provincial level”.

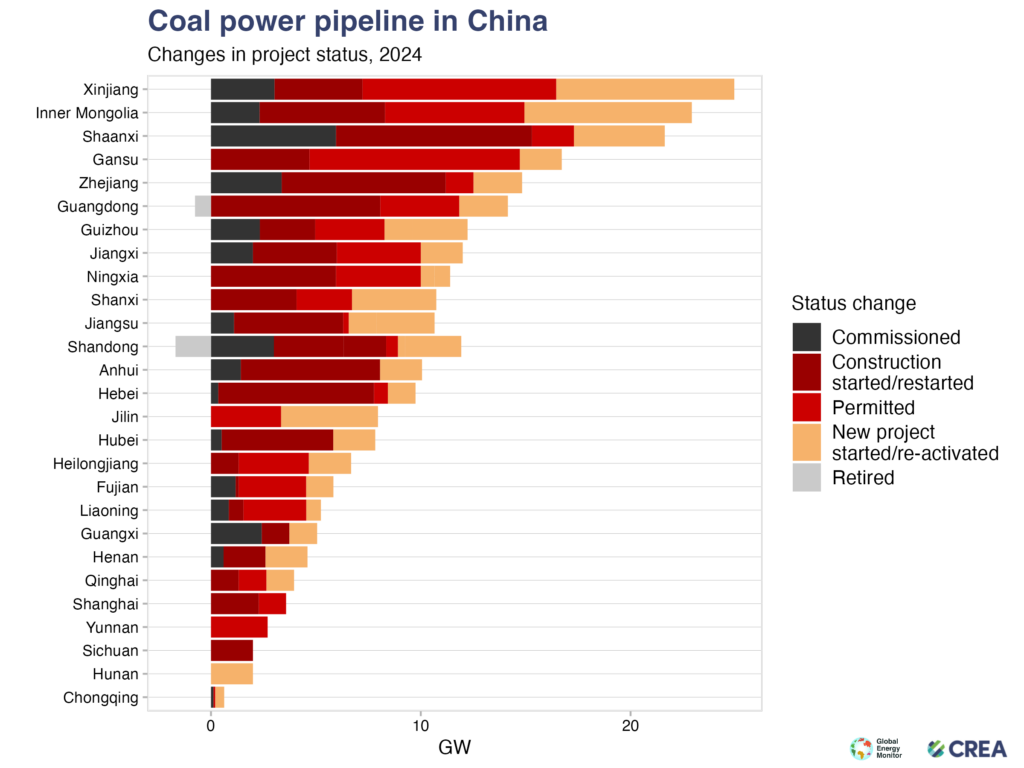

It adds that major coal-producing provinces – such as Xinjiang, Inner Mongolia, Shaanxi and Gansu – were also commissioning and building the most new coal power, as shown in the map below. However, China’s biggest coal-producing province, Shanxi, was not among the provinces with the most activity around new coal power in 2024.

‘Undermining’ the energy transition

The rapid buildout of coal could combine with structural features of the power system that favour the coal industry, the report says, to limit renewables’ ability to become China’s main provider of electricity.

China installed record amounts of renewable energy capacity in 2024, bringing total solar and wind capacity up to 890GW and 520GW, respectively. Coal capacity in 2024 was 1,200GW.

The growing amount of low-carbon electricity in China’s mix was expected to cover new demand and reduce coal’s importance in the system, in a policy known as “establish [new systems] before breaking [old ones]” (先立后破).

However, the report notes, the flurry of new coal construction “makes it increasingly difficult to achieve” this. Instead, it says there is a risk that renewable energy will be treated as a supplementary power source “layered on top” of coal.

This is partly due to several policy structures that prioritise the use of coal power and protect the industry’s interests, it explains.

Most power grids lock in coal-power supply through mechanisms such as medium- to long-term contracts for purchasing power and long-term coal supply agreements, obligating provinces to use a certain amount of the fuel, even when other sources of electricity are more cost-effective.

Provincial governments are also moving away from requiring power purchase agreements (PPAs) to include a minimum share of solar and wind, the report says, resulting in “an uneven playing field where coal power remains insulated from risk while wind and solar developers face price fluctuations and uncertain demand”.

The development of new coal-power plants will “further limit grid space for renewables”, it adds, making it harder for solar and wind power generators to gain significant market share.

Coal’s predominance in the system may have also led to a substantial recent uptick in curtailment of renewable energy. According to calculations in the report, the final quarter of 2024 likely saw a curtailment rate of around 5.5%, rather than the officially reported 3.2%.

The report attributes this to “structural constraints”, rather than weather-driven availability of solar and wind resources.

Opportunity for change in 2025

Forecasts by the coal industry signal that it expects the coal-power sector to continue growing, causing “increasingly unsustainable conflict” between China’s energy security and low-carbon policies, the report notes.

The report suggests strong policy direction in 2025 would be needed to counteract coal’s dominance in the energy system.

This could be achieved, firstly, by reducing the amount of coal in the energy system, such as by setting “ambitious and measurable” targets for reducing coal consumption, phasing down coal plants, utilisation of coal plants in operation and uptake of renewables.

Other potential levers could include ending new coal-power plant approvals and accelerating the retirement of older units.

Secondly, the report points to reform of the mechanisms that steer power providers towards coal – including reducing the amount of coal covered in long-term PPAs and coal supply agreements – and prioritising grid reform and the development of spot markets.

These steps, it argues, would “help implement China’s ambition to phase down coal, create space for renewables, and drive a cleaner, more efficient energy system”.

-

China’s construction of new coal-power plants ‘reached 10-year high’ in 2024