Chance of a very cold UK winter falls to less than 1% by 2100, new study suggests

Robert McSweeney

07.06.15Robert McSweeney

06.07.2015 | 4:00pmThe odds of the UK having a winter as cold as the one in 2009-10 will drop to less than 1% by the end of the century as global temperature rise, researchers from the UK Met Office say.

The new research combines long-term projections of climate change with the yearly ups and downs of the UK’s notoriously changeable weather.

The results suggest that very cold winters and wet summers will become less and less likely, but the research says we should still expect them from time to time.

Cold snap

Climate projections tend to focus on how the typical weather of each season will change in the future. Yet British weather is often anything but typical.

Projections of climate change tell us that UK winters are likely to get milder. Yet the winter of 2009-10 was the coldest in England and Wales for over 30 years, with average temperatures around 2C below the 1971-2000 average.

This “apparent contradiction” led some parts of the media to create confusion by claiming that our climate isn’t warming at all, say the authors of a new study in Nature Climate Change.

But there isn’t a contradiction at all, they say. And so they set out to show how a cold winter or a wet summer could still happen in a much warmer world – even if they are much less likely.

Weather and climate

The researchers used the ‘UK Climate Projections 2009’ (UKCP09 ) – a set of projections of our future climate averaged into 30-year chunks, from 2010-2039, all the way to 2070-2099. They then combined them with model projections that are averaged over just a single year, and thus include more of the year-to-year variability in our weather.

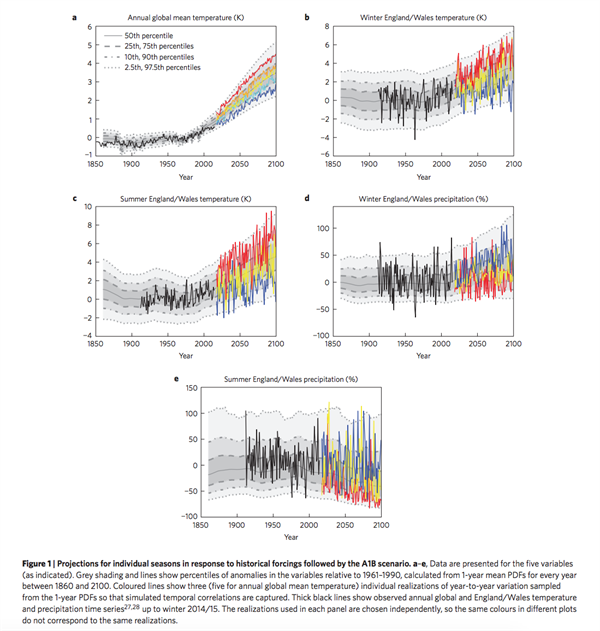

The resulting graphs, shown below, illustrate how different aspects of our weather are expected to change under a moderate emissions scenario. The black lines show observed changes and the red, blue and yellow lines show three (of many) different runs of their climate model.

Observed (black lines) and projected (coloured lines) changes temperature/rainfall for individual seasons under the A1B emissions scenario for England and Wales. Data show difference from the 1961-90 average. Source: Sexton and Harris (2015)

The results show how even with a clear climate change trend, we are still likely to be on the receiving end of some highs and lows of British weather, the researchers say.

For example, Graph B shows winter temperatures in England and Wales rising through the century. So, the chances of a winter like 2009-10 drop from 6% to just 0.6% by 2100, the study finds.

Yet despite the overall trend, there will be some winters that are warmer (red line) than average, and some colder (blue).

Similarly, with summer rainfall in Graph E, you can see a general decrease in expected rainfall, but we will still see some wet summers (blue lines) and others that are even drier (red).

Over the next 20 years, the likelihood of a wet summer will be around 35-40%, but this drops to about 20% by the end of the century, the study says.

Summers will also get hotter, the researchers say, with the chances of a very hot summer – that currently happen around once every 20 years – rising to around 90% by 2100.

The benefit of presenting projections in this way is it makes it easier to see that a wet summer or cold winter doesn’t mean climate change isn’t happening, the paper says:

“In other words, because of climate variability, cold winters do not immediately disappear under climate change, and their occurrence does not contradict the theory or projections.”

Removing confusion

The research gives a different perspective on future climate, says lead author Dr David Sexton, Head of Scenarios Development at the Met Office. He tells Carbon Brief:

“So the original UKCP09 headlines told us how typical seasons might change, but the new research provides a more detailed picture of the range of seasonal temperatures and rainfall we could see in a given year.”

Sexton hopes that presenting our potential future climate in this way will reduce the chance for public doubt when we have a season of unusual weather:

“To remove any confusion, we included year-to-year variability, so that the projections provide the range of seasonal temperature and precipitation that the UK might experience under climate change.”

And with the Met Office working on the next update of UKCP09, this new approach to climate projections could well be the way forward, says Sexton. This would not only help offer clearer messages to the public, but also allow more informed decisions about how we adapt to our changing climate, he adds.

Main image: A snow-covered village in the UK.

Sexton, D.M.H. and Harris, G. R. (2015) The importance of including variability in climate change projections used for adaptation, Nature Climate Change,doi:10.1038/nclimate2705

-

The odds of the UK having a winter as cold as the one in 2009-10 will drop to less than 1% by the end of the century as global temperature rise