CCC: UK ‘needs negative emissions’ to comply with Paris climate deal

Simon Evans

10.13.16Simon Evans

13.10.2016 | 12:01amThe UK will have to use negative emissions to comply with the Paris Agreement on climate change, according to its official climate advisers.

Plans to start using greenhouse gas removal technologies by 2050 should be drawn up immediately, says the government’s Committee on Climate Change (CCC). It adds that global use of these technologies “will be central” to meeting the Paris goal of net-zero emissions.

However, the CCC warns that they are not a substitute for reducing emissions now. It says the UK must “vigorously pursue” efforts “with urgency” to meet its existing carbon budgets to 2030.

In a second report, the CCC says that these goals are written into the domestic Climate Change Act. As such, leaving the EU would have no impact on the legal requirement to comply.

Carbon Brief runs through the CCC’s recommendations.

Paris Agreement

The Paris Agreement, agreed last year, will enter force on 4 November. Its signatories agree to limit global temperature increases to “well below 2C” above pre-industrial levels and to make efforts to keep them below 1.5C.

It also commits them to reaching a “balance” between anthropogenic sources of emissions and sinks – a goal widely interpreted as being roughly equivalent to achieving net-zero emissions.

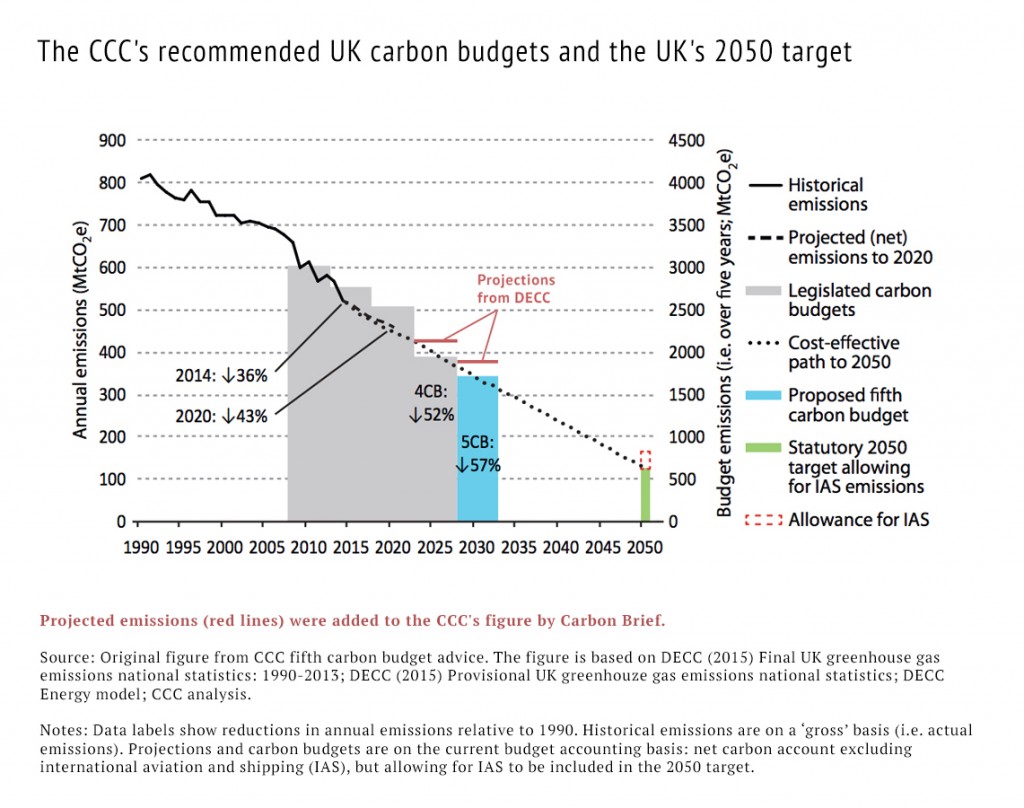

The CCC, asked to assess what the deal means for the UK, in January said there was no need to amend the fifth carbon budget covering 2028-2032. Now, in light of the Paris deal, it has looked at the UK’s long-term target to cut emissions in 2050 by 80% below 1990 levels.

The CCC says:

The CCC also says that alternative measures of fairness “nearly all point to more ambitious [UK] action than the existing targets”.

Nevertheless, the CCC says the UK’s existing carbon budgets and its 2050 target should not be changed, saying “they are already stretching and relatively ambitious compared to pledges from other countries”. It adds that it is “too early” to set a target date for the UK to reach net zero.

Explaining the committee’s thinking, Matthew Bell, CCC chief executive, tells Carbon Brief:

Net zero

Reaching net-zero emissions will be a huge challenge. The CCC’s reluctance to recommend a target date at this point stems in part from a lack of evidence on how the UK could get there.

However, the CCC does have one clear message on what it will entail:

- Explainer: 10 ways ‘negative emissions’ could slow climate change

- In-depth: Experts assess the feasibility of ‘negative emissions’

- Timeline: How BECCS became climate change’s ‘saviour’ technology

- Guest post: Do we need BECCS to avoid dangerous climate change?

- Analysis: Is the UK relying on ‘negative emissions’ to meet its climate targets?

Even the most ambitious application of all known options to reduce UK emissions would fail to reduce them to zero, the CCC says.That’s why it thinks the UK will need greenhouse gas removal options, often referred to as negative emissions, to balance the residual.

The CCC already includes negative emissions in some of its scenarios towards the 2050 target. Now it is saying that these options “will be required” by the UK, and the world.

“[Negative emissions] globally and in the UK will be central to realising the Paris aim of balancing greenhouse gas sources and sinks from human activities, given the difficulty of removing all sources.”

This advice is in line with the latest science: the vast majority of 1.5C scenarios rely on greenhouse gas removal options, despite the challenges, uncertainty and disagreement over their use. Resolving these issues will only be possible with research and large-scale tests of deployment, says Prof Pete Smith, chair in plant and soil science at the University of Aberdeen.

Prof Smith tells Carbon Brief:

The UK should start now to draw up a strategy for deployment of negative emissions “at scale by 2050”, the CCC says, given the time needed to develop options and bring technologies to market.

If negative emissions are less feasible or less effective than expected, however, then more stringent emissions cuts will be required. Glen Peters, senior researcher at Norwegian climate research institute CICERO, tells Carbon Brief:

Distraction

As well as the risk of under-delivery, giving attention to greenhouse gas removal could be seen as a distraction from cutting emissions. As Peters puts it: “It’s pretty convenient from a political perspective. Someone else can do it with negative emissions in future.”

However, the CCC cautions strongly against this. Its report says:

At a briefing for journalists, the CCC’s chair Lord Deben said:

The CCC says a maximum of 70m tonnes of CO2 could be sustainably removed in the UK each year. This is equivalent to less than 10% of UK greenhouse gas output in 1990, meaning emissions would still have to be cut by more than 90% in order to reach net zero overall.

Prof Kevin Anderson, deputy director of the Tyndall Centre for Climate Change Research, told Carbon Brief in September:

Crunch time

In theory, the UK’s Climate Change Act allows little room for complacency. It says the government must set out how carbon budgets will be met “as soon as practicable” after setting them.

Lord Deben says:

The previous government had committed to doing this by the end of the year. Following the EU referendum, an emissions reduction plan is not now expected until early 2017.

UK greenhouse gas emissions since 1990 and the CCC’s cost-effective path to the 2050 target (green bar). The grey bars show the UK’s first four carbon budgets. The blue bar is the proposed fifth budget. The red lines show emissions projections from the Department of Energy and Climate Change. Each budget includes an allowance for international aviation and shipping emissions (IAS). Source: CCC fifth carbon budget advice and projections from DECC. Chart by Carbon Brief.

In order to comply with the Act, the plan must chart a credible path to meeting the fifth carbon budget. Section 13 of the Act says:

In a shot across the government’s bow, legal NGO ClientEarth this week issued a report saying that its 2011 Carbon Plan is in breach of the Act. The government, by its own admission, does not consider that plan sufficient to meet the fourth carbon budget.

In the government’s words: “There is currently a shortfall against the fourth carbon budget…where our emissions are projected to be greater than the cap set by the budget.”

This shortfall is substantial. The CCC says current policy will, at best, deliver only half the emissions savings required.

Brexit

For some, the solution to the challenge of meeting the UK’s carbon budgets is to relax them. After the UK vote to leave the EU, some saw a risk of a climate policy bonfire, given many of those that supported the vote to leave also favour weakening or even abandoning UK climate action.

However, three key factors will remain unchanged once the UK leaves the EU, CCC chief executive Matthew Bell tells Carbon Brief. First, the scientific evidence on climate change. Second, the Paris Agreement and, third, the UK’s Climate Change Act.

A second CCC report, also published today, emphasises that UK climate goals are written into UK law. The targets have not changed and there is much to do if the UK is to meet them. It says:

The EU’s emissions trading system (EU ETS) would leave the largest hole if it were dropped when the UK left the EU. More than half of the savings the UK needs to make over the next 15 years are expected to come from the power sector and industry, whose emissions fall under the EU ETS.

Other relevant EU laws include car fuel efficiency standards, product labelling and efficiency standards, as well as regulations covering fluorinated greenhouse gases such as HFCs.

Conclusion

The need for urgent action to cut UK emissions is the overarching message from today’s CCC reports. The CCC makes clear that the UK will sooner or later have to accelerate its efforts to match the ambition of Paris, but says the first priority is to get up to speed against existing targets.

Moreover, it won’t be clear how the UK can meet the Paris goal of reaching net-zero emissions until more work is done to investigate negative emissions – hence the need to start developing a strategy on greenhouse gas removal now.

The CCC’s refusal to call for tougher UK targets will dismay those that see the Paris Agreement as a clear signal of the need to raise ambition. In a statement, Friends of the Earth chief executive Craig Bennett says:

Yet the CCC’s reluctance to reopen the debate over UK targets also reduces the risk of them being weakened. Defending the decision, Bell says: “I think, rightly, the committee has a very high threshold for when should we set new targets.”