CCC: One fifth of UK farmland must be used to tackle climate change

Josh Gabbatiss

01.23.20Josh Gabbatiss

23.01.2020 | 12:01amAn “urgent” overhaul of the UK’s land and agricultural sector will be essential to meet the government’s legally binding net-zero target, says the Committee on Climate Change (CCC) in a new report.

The government advisors say that with adequate support, nearly two-thirds of emissions from the land sector can be cut by 2050 without hampering UK food production.

While previous CCC work has demonstrated the feasibility of reducing land emissions while benefiting biodiversity and climate adaptation, this report proposes specific policies to achieve these cuts.

Chief among the recommendations is a call for one-fifth of the nation’s farmland to be transformed over the next 30 years into landscapes designed to store carbon and cut emissions.

As the UK prepares to leave the EU and, therefore, its Common Agricultural Policy (CAP), the committee says the time is ripe to launch a suite of “new, transformative policies” to help meet these targets.

By its assessment, the proposed measures would cost around £1.4bn every year, but would generate benefits worth £4bn. As it stands, the UK spends £3.3bn annually through the CAP.

Describing it as “one of the most important reports that we have ever produced”, CCC chair Lord Deben stated these policies would be vital to meet the net-zero goal by 2050. “We are in a race against time,” he told a press briefing:

“For me this is a key moment, because we are now moving from…determination, commitment, electoral discussions, to delivery.”

- Agricultural shift

- Low carbon and more productive

- Tree planting

- Peatlands

- Bioenergy crops

- Diets and food waste

- Next steps

Agricultural shift

Given their status as “stewards of the land”, Lord Deben said the cooperation of farmers in these measures will be essential.

Central to the committee’s proposals is “a high uptake of low-carbon farming practices and releasing 22% of land out of traditional agricultural production for long-term carbon sequestration”.

Chris Stark, the CCC’s chief executive, laid this out clearly in a conference call with journalists ahead of the report’s publication:

“The clear advice in this report is that we need to see a fifth of agricultural land taken out of traditional agricultural production and moved into long-term, natural carbon storage, that means growing trees, restoring soils…There is inevitably some uncertainty about the precise ways in which that needs to be achieved, that means a really strong message to government: They have to get started on this soon.”

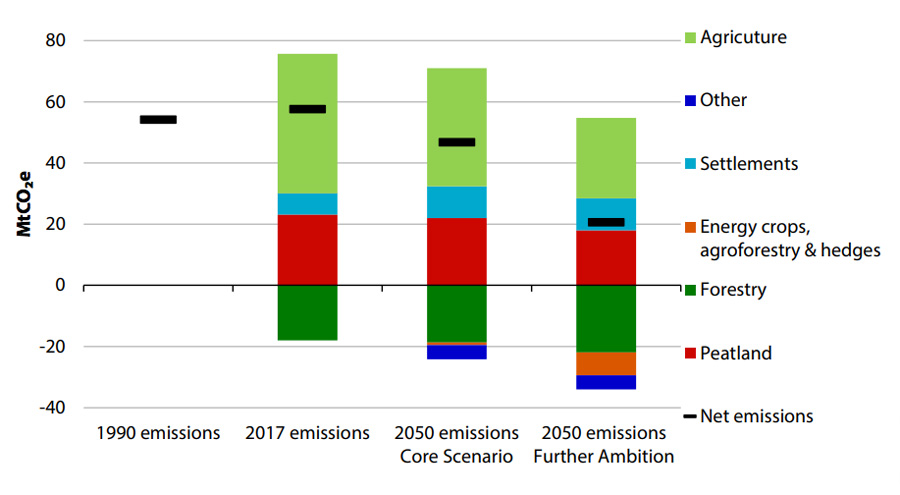

The committee notes that emissions from UK land use, forestry and agriculture were 58m tonnes of CO2 equivalent (MtCO2e) in 2017, as the chart below shows. This is 12% of the nation’s annual greenhouse gas emissions, with farming alone accounting for 46MtCO2e (9%).

While agriculture’s share of the total is a relatively small proportion compared to transport and energy, the volume has hardly changed for decades – as the chart below shows. The sector is set to take up a considerable portion of the UK’s residual emissions by 2050.

The inaction on emissions has partly resulted from a CAP that prioritises food production and “has led to a distorted set of uses for land that do not reflect the need to mitigate climate change”, the CCC says.

New policies under development mean the government has an opportunity to change the way the country is farmed and shift the system towards payments to farmers for public goods.

Meanwhile, the National Farmers Union has set out its own net-zero strategy. While it aims to achieve this ambitious target by 2040 in England and Wales, it diverges from the CCC’s recommendations on some key issues.

Stark tells Carbon Brief that while there are many similarities between his committee’s scenarios and the ones laid out by the NFU, the key distinction is the CCC calls for much larger emissions cuts from land-use changes, driven by improvements to productivity and dietary changes:

“We do not rely on the more speculative measures in the NFU analysis, including biochar and enhanced weathering, or for grasslands on minerals soils to continually sequester carbon, which is not supported by the current evidence.”

Low-carbon and more productive

Based on land-use scenarios from last year’s net-zero report, the CCC concluded a 64% reduction in agriculture, land use and peatland emissions from 58 MtCO2e in 2017 to 21MtCO2e would be feasible, a cut of 37MtCO2e.

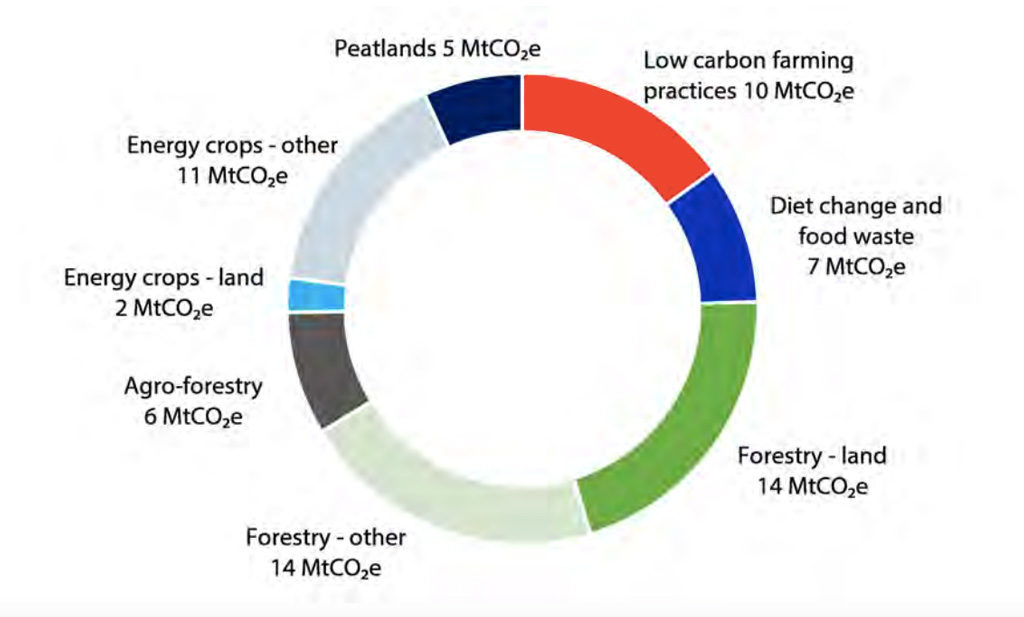

These savings are made up of contributions from a range of changes, as the chart below shows. The single largest source of emissions cuts is from forestry. However, changes in other areas, such as diet and reduce food waste, are key to allowing expanded forest cover.

Another key area is described as “low-carbon farming practices”, such as controlled release fertilisers to lower overall usage, improving livestock health and slurry acidification, which can cut ammonia emissions.

Combined with low-carbon fuels used in farm buildings and machinery, the CCC estimates these measures could deliver 10MtCO2e of emissions savings by 2050.

Stark says these mainly comprise “low regret” options and that the CCC has presented a package of options it feels could mostly be delivered through new regulations.

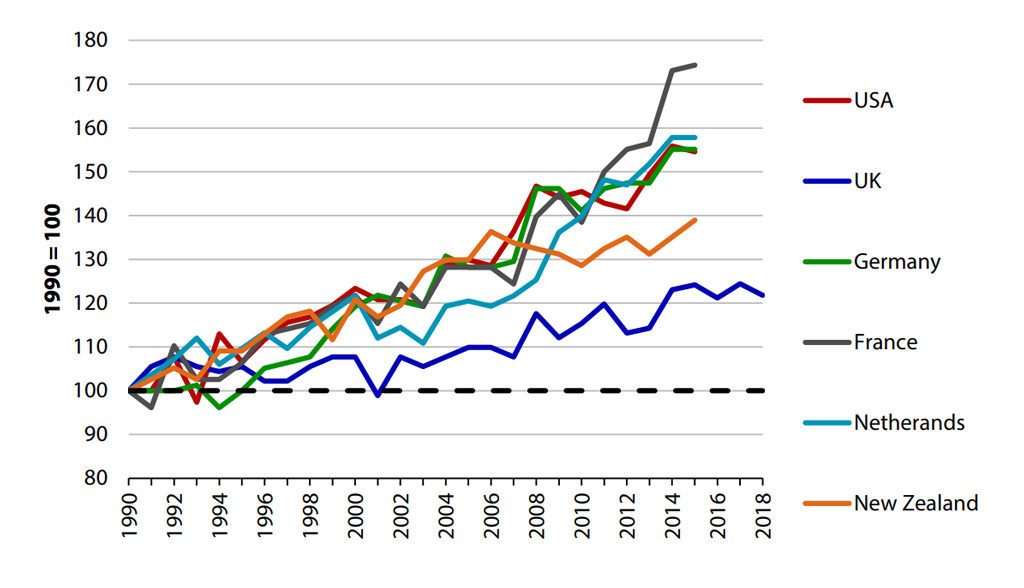

The CCC also highlights the need to tackle the “productivity gap” in UK agriculture, which has seen productivity growth lag behind other countries, leaving many British farmers reliant on CAP payments. (The chart below shows UK productivity compared to some of its competitors.)

Stark tells Carbon Brief this is a “complex issue and not very well understood”, but that data shows general cropping, cereal and dairy farming productivity has risen but livestock production has fallen since 1990.

The report lists providing skills, developing rural infrastructure and R&D as ways to address this issue. It notes that improved productivity would help free up land for other uses.

The report also mentions cutting methane from UK farms, something it says will have “unambiguous benefits for the global climate”.

It suggests incorporating measures to reduce methane emissions in the government’s clean air strategy and adding methane-inhibiting additives to livestock feed by 2023.

Finally, the report emphasises that cutting emissions does not need to mean increasing food imports. This is particularly pertinent considering farming practices in other countries can have a far higher carbon footprint, the CCC notes, meaning there is a risk of “carbon leakage” if imports increase.

Tree planting

Afforestation has been in the spotlight in recent months, with rival political parties engaging in an “arms race” during the recent general election over who could pledge to plant the most trees.

Even the climate sceptic US president Donald Trump signalled his intention at the World Economic Forum in Davos this week to join the Trillion Trees Initiative. As Stark puts it: “It’s a good time to be a silviculturist”.

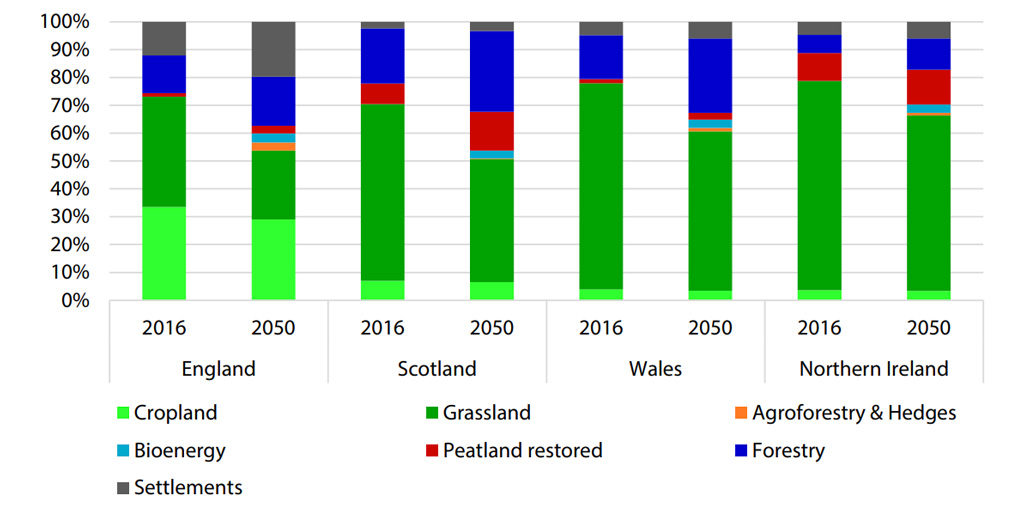

By 2024 the CCC want to achieve a minimum of 30,000 hectares of new broadleaf and conifer woodland each year until 2050, amounting to around 100m trees each year. This would increase woodland cover in the UK from 13% to at least 17%.

Stark says the nation has managed similar rates of planting before – as recently as the 1980s – so the CCC thinks it can be achieved, but how it can be achieved, he says, “is the most eye-catching of our policy recommendations in this report”.

In order to provide land managers with secure income as well as value of money for the taxpayer, the committee has “borrowed from the successful policy experience” of the renewable energy sector.

As with the “contracts for difference” (CfDs) used to support new windfarms, the CCC proposes a “feed-in tariff” where there is an annual auction for new tree plantations, setting a fixed price for those who deliver the new trees.

Alternatively, the committee recommends a trading scheme where farmers would receive carbon credits, which they could hold or trade in for payment.

Whichever financial incentive is chosen, Stark tells Carbon Brief it would have to be designed to encourage not only quantity but quality of plantation, ensuring proposals “take account of local geography, physical and climatic conditions”.

Alongside improved woodland management, the CCC says its target would deliver annual emissions sequestration of 14MtCO2e in forests, plus 14MtCO2e from harvested materials. It also estimates an additional 6MtCO2e in savings could be achieved by 2050 by planting trees on agricultural land, which could still be used for its original farming function.

Peatlands

The report calls for the large-scale restoration of at least 50% of upland peat and 25% of lowland peat across the country. This means allowing water to flow back through degraded peatland so it is able to store carbon effectively.

Here, the CCC has some firm recommendations. It has called for a ban this year on the rotational burning of peatlands, a controversial practice said to provide ideal conditions for grouse shooting.

The committee also urges a ban on the extraction and sale of peat for horticultural use to come into force before 2023.

In both cases, Stark says that voluntary approaches to tackle these issues “have not worked” and, therefore, more urgent measures are required.

Other methods to preserve peat include an obligation for any water companies and owners of peatland within sites of special scientific interest (SSSIs) to undertake their own peatland restoration, when appropriate.

The CCC says additional peatland restoration should receive public funding. If it proves possible to verify emissions reductions accurately, it says a trading or auctioning system could even be introduced, similar to the one proposed for afforestation.

Bioenergy crops

The committee’s net-zero advice, issued last year, made significant use of bioenergy with carbon capture and storage (BECCS) – where plants are burned for power and the resulting CO2 is stored underground – towards the 2050 target.

The “negative emissions” from BECCS and other “greenhouse gas removal” options would offset residual emissions from farming and other parts of the economy.

In order to realise this ambition, the UK will require more agricultural land to be devoted to energy crops, the CCC says. (The chart below shows how bioenergy could expand under its proposed scenario, as well as how other sectors will change in terms of land use.)

Its new report calls for the expansion of such crops, including miscanthus and short-rotation forestry, to grow to around 23,000 hectares added each year from the mid-2020s.

It estimates that this will deliver 2MtCO2e emissions savings in the land sector, as well as an additional 11MtCO2e from harvested products, for example when paired with CCS technologies, by 2050.

For now, it recommends providing financial support for this bioenergy through existing commitments such as the Renewables Obligation and Contracts for Difference.

When it comes to BECCS, Stark tells Carbon Brief developing a funding mechanism for negative emissions technologies is one of the main challenges, as is actually deploying CCS at scale. “The government has committed £800m to [CCS] in the latest manifesto and is consulting on appropriate business models to develop it,” he says.

The CCC has previously recommended that the UK should have a strategy to develop greenhouse gas removal options, as well as a new bioenergy strategy.

In order to support the UK production of bioenergy crops, the report suggests making an agreement with biomass combustion facilities to source a minimum of their feedstock from domestic sources, as well as offering low-interest loans for energy crops.

When expanding bioenergy crops, Stark also notes that it is important to ensure there are “no trade-offs”, for example with biodiversity. He says the CCC assumes the planting of perennial energy crops only, which could actually benefit nature if replacing arable land, as they require less chemical fertiliser.

Diets and food waste

The CCC’s net-zero report suggested a 20% shift away from beef, lamb and dairy to alternative protein sources per person as part of meeting the 2050 target. Diet change is seen as a critical way of cutting emissions from the food chain, as well as freeing up land for other uses.

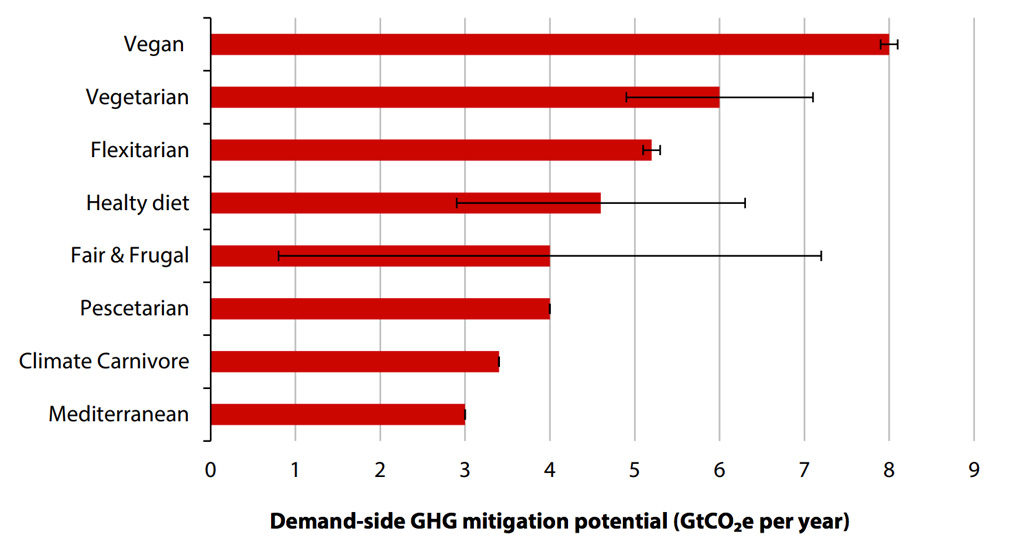

This trend would be more aligned with the healthy eating guidelines already issued by the government and indeed a similar shift already appears to be underway. The chart below shows the relative impact of different diets on greenhouse gas mitigation.

Although it is not mentioned directly in the CCC report, data from the government’s long-running family food survey suggests that UK beef consumption in 2018 had already fallen by around a quarter since 1990 and lamb by around half.

While the report acknowledges this shift, it also notes that “current trends are not likely to be sufficient to deliver the changes in our scenario by 2050”.

As a result, the committee concludes that policy intervention is likely to be necessary – for example, developing methods to steer people towards different diets and offering support for research into new protein sources.

This dietary switch is also an important consideration when trying to avoid any “offshoring” of emissions. The committee notes that if consumers simply switched from relatively lower-carbon UK beef to higher-carbon Brazilian cuts, it will undermine efforts to cut emissions.

Stark tells Carbon Brief avoiding this sort of unwanted outcome would require “trading policies with strong sustainability standards”, alongside measures being implemented to encourage a switch to healthier diets.

If an initial phase of “information provision, skills support, and encouraging greater accountability of business through clear and robust metrics and mandatory reporting” is not enough to drive the necessary shift, Stark says “a second stage will need to look at stronger options, whether regulatory or pricing”.

The report also highlights the need to shave 20% off the 13.6m tonnes of food waste produced in the UK every year. Suggested short-term policies include new, more effective date labels for food. By 2023, it calls for mandatory separate collection of food waste across the UK to cut methane emissions generated during disposal.

“These are very much low cost, low regret measures overall because reducing food waste is something that makes sense almost in any circumstance,” Stark noted.

Next steps

The CCC says its new policies will “kick start” the shift to both low-carbon farming and a switch from agricultural land to carbon sequestration and emissions cuts.

In some instances, new regulations will be required, such as laws to further control agriculture emissions, and ban practices, such as peatland burning and peat extraction.

Many of the measures will require considerable funding. The CCC says the necessary £1.4bn per year can be provided by a combination of public and private funding.

For example, it suggests the auctioned contracts or carbon trading scheme used to encourage afforestation activity could be funded by a levy on high-emitting industries, such as fossil fuel suppliers and airlines.

At the same time, public funding could be used to encourage tree planting on farms when it would not otherwise be financially viable and to encourage additional afforestation benefits such as flood management.

Other areas it says should be eligible for public funding include peatland restoration and low-carbon methods such as “precision farming”, which might otherwise incur a cost to the farmers themselves.

The CCC emphasises both the £4bn per year social benefit of its recommendations and the high cost of the CAP compared to its £1.4bn estimate, as Stark explains:

“At the moment, we are handing out £3.3bn per year to land managers and farmers through the common agricultural payment system, which of course focuses on food production. We know that will change after we leave the EU – we don’t know how the quantum of funding will change but we know that change is coming.”

Among the suggested benefits are better air quality, health improvements and flood alleviation. The largest projected benefit comes simply from emissions cuts, which the CCC values at £2.7bn annually.

Stark adds that the £4bn is a “conservative estimate”, noting that “we haven’t for example tried to value the gains you get from biodiversity of improved water quality”.

Money is not the only barrier to implementing the CCC’s recommendations. The report also emphasises the “wider policy levers” that will be required to support shifts in behaviour and incentivise change.

This could include measures to “nudge” consumers into avoiding food waste and the public sector taking the lead by providing plant-based meals. It could also address other barriers, such as the tax treatment of woodlands, which might disadvantage farmers wanting to switch to forestry management.